The Framingham Heart Study | New England’s Gifts

One day in 1948 a woman named Mary H. Sullivan became the very first Framingham Heart Study participant. More than 11,000 participants later, the people of Framingham, Massachusetts, 21 miles down the Mass. Turnpike from Boston, still troop along to the clinic to be studied. In all these years, the Heart Study has never treated […]

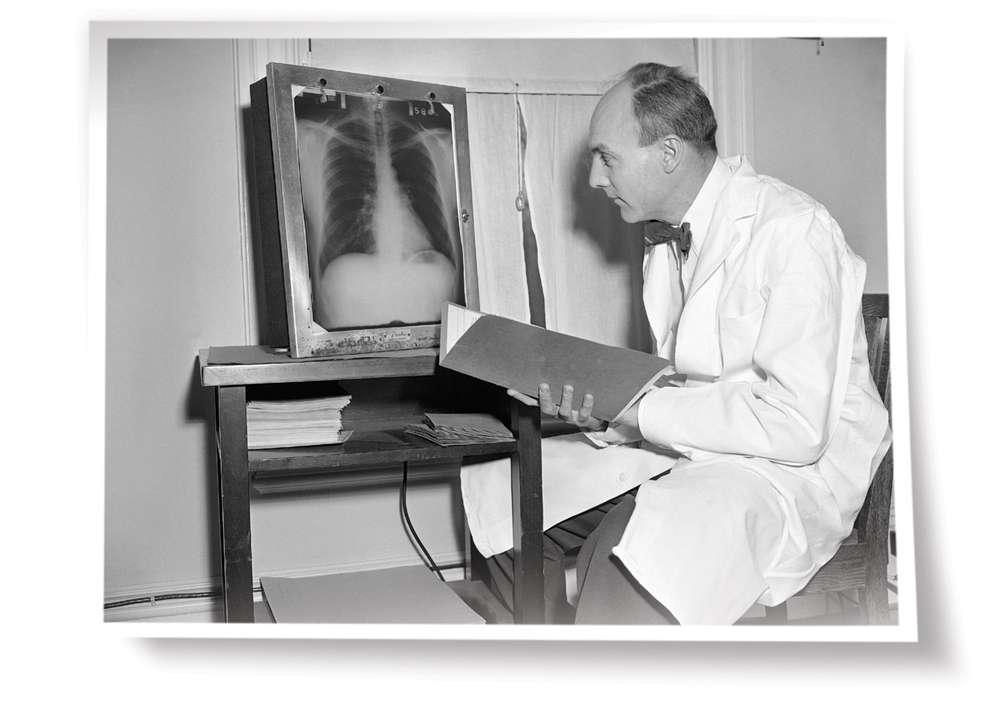

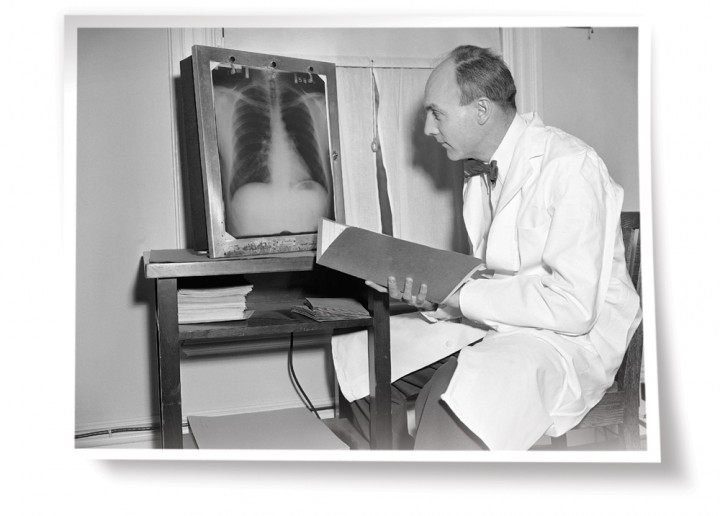

April 1952: Epidemiologist Thomas Royle Dawber, M.D., director of the Framingham Heart Study from 1949 to 1966, checks

a participant’s x-ray.

One day in 1948 a woman named Mary H. Sullivan became the very first Framingham Heart Study participant. More than 11,000 participants later, the people of Framingham, Massachusetts, 21 miles down the Mass. Turnpike from Boston, still troop along to the clinic to be studied. In all these years, the Heart Study has never treated anyone, and yet these participants have changed the way we live and die, for which we, the people of the United States, owe them, the people of Framingham, a great debt.

Photo Credit : Frank C. Curtin/AP Images

In world medicine Framingham is famous for “the Study,” as everyone in town calls it: the longest-running and arguably the most productive public-health research project in American history. For most of that time, the Study has been federally funded, but for all of its lifetime, it has run on pure altruism. The altruists are the ones in bathrobes and slippers shuffling around a cramped former convent near downtown Framingham. They wear their laurels lightly. The participants have always come here on their own time, receiving neither pay nor direct benefits. They go to the clinic periodically to be stuck, prodded, “imaged,” sampled, and intensely questioned for the good of humankind.

“Framingham data” have been published in hundreds of scientific papers and cited in thousands more.Framingham data established the connection between high blood pressure and stroke. Present yourself today with a blood pressure of 140/90 and your doctor will probably start bugging you about being “hypertensive.” That’s Framingham data. Framingham unequivocally linked cigarette smoking to coronary artery disease, giving the U.S. Surgeon General the ammunition in 1964 to move against smoking—not just as a cancer risk, but as a threat to the American heart. When the tobacco companies countered with low-tar and strongly filtered brands, Framingham data demolished the notion of a “safe” cigarette.

Framingham data also gave us new kinds of guilt. The Study demonstrated that inactivity was linked to stroke, pushing millions of chair-bound Americans into running shoes. Most notoriously, Framingham added the word cholesterol to the common tongue; ice cream, bacon, and steak have never tasted the same. Framingham data later refined cholesterol into “good” and “bad” components: high-density lipids, or HDL, versus low-density lipids, or LDL. The ratio of the two lipids as well as their total level were risk factors for arteriosclerosis.

Indeed, Framingham data gave us the phrase “risk factor.” In 1961 doctors Thomas R. Dawber and William B. Kannel (respectively, the first and second directors of the Heart Study) coined the term for a joint paper in the Annals of Internal Medicine. “Factors of risk,” the doctors wrote, were those conditions or behaviors that increased the odds of developing a pathological condition.

Photo Credit : Frank C. Curtin/AP Images

By the late 1940s heart disease had become the nation’s leading cause of death. The federal government’s response, through the newly organized National Institutes of Health (NIH), was the Framingham Heart Study. Until Framingham, most studies of epidemics had looked at the already sick (say, people with TB) or at occupational groups (say, coal miners), seeking patterns of exposure to disease. This would be a different kind of epidemiology: a large-scale, long-term study that would start with an enormous cohort of “healthy” men and women with nothing in common but a post office. They would be between 30 and 60, living in a town where they could be examined and watched closely for 20 years. It sounds cold-blooded, but the idea was to wait and see which members would develop heart disease. What physiological conditions, exposures, habits, and family histories did they have in common?

The Study would need at least 5,000 qualified participants to submit to intrusive physical exams every other year for the next 20 years, or until death did them part. In 1948 Framingham had only about 10,000 adults between the ages of 30 and 60; the Study would need a volunteer rate of 50 percent. Incredibly, the citizens of Framingham signed up. Volunteer “captains” fanned out through town to enroll families, church congregations, and whole blocks of people for the first cohort group. One participant summed up the feelings of thousands: “I feel good,” she said, “knowing that they found something that helps people do better.” Said her husband, “It’s not often that you get a chance to participate in something that has had such startling impact.”

—“Thank You With All Our Hearts,” by John Fleischman, July 1998