Yankee Classic | “A Lesson from the Chess Master” by Bill Simmons

In Harvard Square you can play chess with one of the best players in America for two dollars a game. The humiliation is free.

“A Lesson from the Chess Master,” October 1995, Yankee Magazine

By Bill Simmons

Editor’s note: On page 8 of the October 1995 issue of Yankee, the list of contributors includes this entry: “Bill Simmons is a Boston-based freelancer. This is his first piece for Yankee.” In the nearly three decades that followed, Simmons (aka “The Sports Guy”) would become one of the most celebrated sports voices in the nation. He spent more than a decade as an ESPN columnist and commentator, and co-founded the network’s “30 for 30” documentary series; he was also the founding editor-in-chief of Grantland. Today Simmons is CEO of The Ringer, a sports/pop culture website that produces “The Bill Simmons Podcast,” which regularly ranks as one of the most-listened-to sports podcasts.

* * *

On a gorgeous Friday in autumn, Harvard Square feels like the center of the universe. A man declaims Scripture. A yodeler makes his rounds. Bagpipes blare in the distance. Beggars wield cups. Students, tourists, and foreigners wallow in the sunshine. If you listen, you might hear ten languages spoken in ten minutes. If you look, you’ll see men and women holding hands, women holding hands, and men holding hands; blond hair and blue hair; people carrying purchases from WordsWorth and Filene’s in shopping bags, and people carrying their life’s belongings in them.

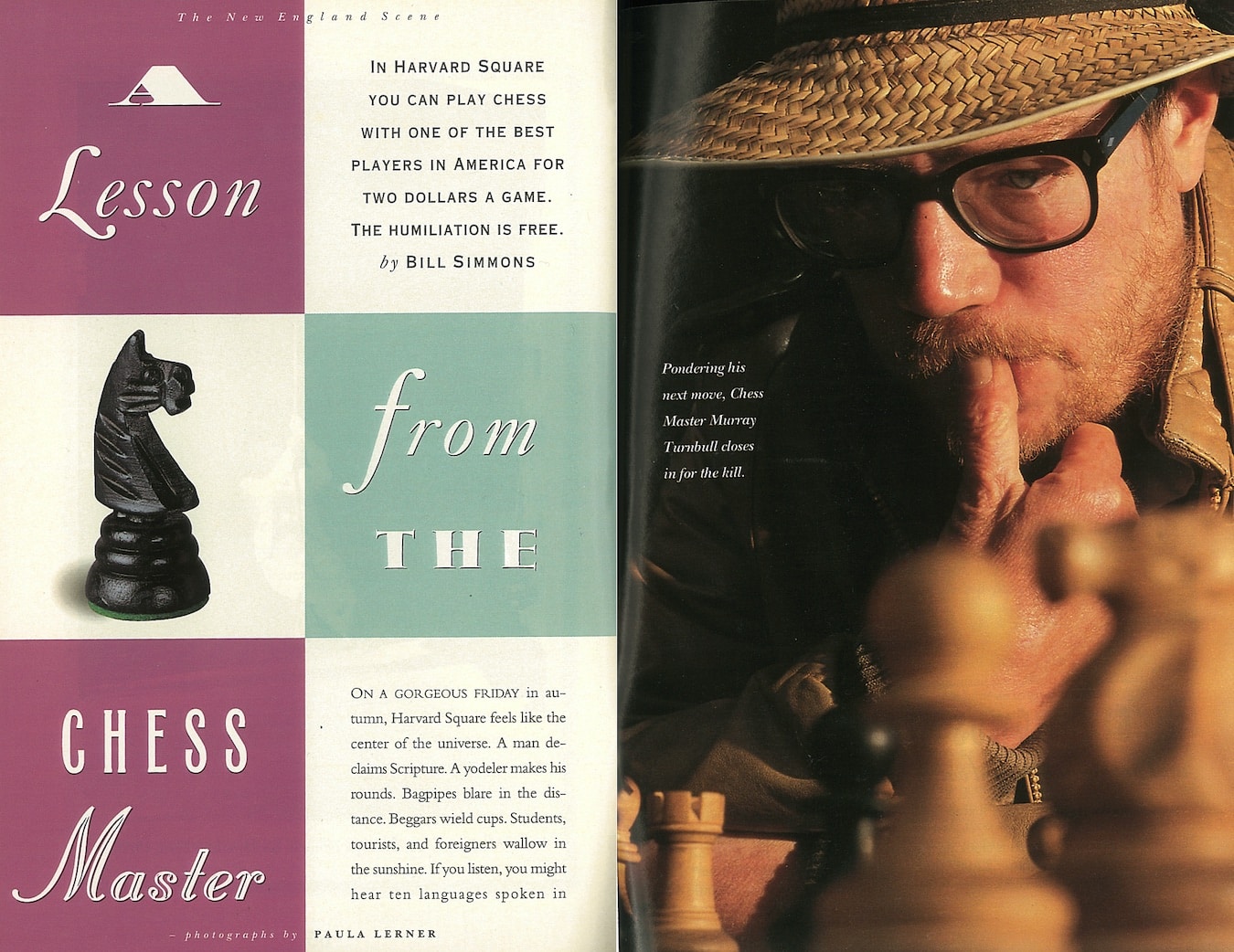

The Chess Master—a.k.a. Murray Turnbull—sits in the midst of the commotion at the front concrete chess table outside Au Bon Pain. He strokes his red beard, staring over the board. He wears a maroon jacket and a beaten, light brown straw hat. Dark brown glasses with thick lenses just past the brim. He wipes his nose with an Au Bon Pain napkin repeatedly. He has a cold.

His opponent moves a pawn forward and bangs a time clock on the table’s edge. (Turnbull gives opponents ten minutes to make a move, himself five.) The Master slides his bishop across the board and punches the time clock, all in one sweeping, awkward motion. He cackles and sips his coffee. He puffs nervously on a cigarette. He constantly heaves back and forth.

The crowd, typically diverse, stares at the board entranced: a male student with a ponytail, a young worker in a deliveryman’s outfit, two businessmen in suits, a woman with a shaved head and nose ring.

The deliveryman is blocking the “Play the Chess Master $2.00” sign.

“Move to the right,” the Master says. “Advertising.”

The Master’s opponent pushes a rook and whacks the clock. “Hmmm,” says the Chess Master. He cackles again—an intimidating cackle, his calling card. He strokes his beard, makes another move-the-piece-punch-the-clock maneuver, and leans back. “This is war!” he says, joking.

The Chess Master puts on a show for his audience. He chatters and heehaws and fidgets. He exhales smoke disdainfully. He spits chess jargon: “You should have moved the K-6 a little earlier.” He accentuates his gawky moves with a comic flair. This is his job, after all.

The clock winds down, and his opponent loses patience and resolve. The Chess Master edges closer to the table and follows each of his opponent’s desultory moves with a rapier-like move of his own. And a “Ha-HA!” for good measure. Soon, mercifully, the game ends. “Mate,” says the Master.

The opponent shakes his head and laughs. “I wish I didn’t make those two mistakes,” he says. “I was going so well.”

This affronts the Master. “I was two pieces up,” he says, frowning, eyebrows raised. “You never should have taken RF-1 when you had knight 6.” Cackle.

They play again. But this time the Chess Master has ruin on his mind. It’s over in three minutes.

An old foe shows up to battle the Master. The new man attempts to secure the middle. He studies the board. The Chess Master turns intense, leaning into the table, rocking. His clock runs down to less than one minute, and he plays frantically, moving-the piece-and-punching-the-clock even faster and more clumsily. His foe, in his haste, exposes his rook. The Master finagles a mate, clenching his fist for good measure.

He hops up to grab coffee. His opponent, Rob, tells me, “Murray’s in the top one percent of all tournament players in the States. I’ve played more than 100 games against the man and lost every time but once. It’s almost fun to lose to somebody when he’s that good.” Rob enjoys two more losses and leaves. No one steps forward. Is it across from the Chess Master. Within seconds I’m pushing pieces aimlessly, and time seems so fleeting, and I keep glancing at the clock, and…

“Mate,” the Chess Master says.

I shake my head.

“You need to build your center,” he tells me.

“What?” My brain is clouded.

“The center. Not only does it protect your king, but it gives you flexibility. You were playing like General Custer—moving straight ahead, blindly.” He nods at me. His thick glasses make it difficult to make eye contact.

I frown. I’m good at chess. I can’t remember my last loss. “I was a little thrown off by the clock,” I say.

“All the time in the world won’t help you if you don’t build up your center,” he tells me. Ha-HA!

“Let’s play again,” I say. I want to beat him so badly I can taste it.

Three minutes later all I taste is defeat.

“Four dollars,” says the Chess Master.

* * *

I return two days later. The Chess Master is there still in the midst of the commotion, quickening his games, trying to finish off his foes in five minutes instead of ten. Bigger crowds mean more money, and people hop in and out of his chair as if it’s on fire.

By three in this productive afternoon, clouds have drifted into Cambridge; it appears rain will hit. I sit across from the Chess Master, giving him a decent game. He fidgets more, which I interpret as a moral victory. I even check his king.

Of course, within minutes my king is in check—checkmate. I shrug, exasperated.

“That was your best game,” the Chess Master says suddenly.

“It was?”

“Yeah. You didn’t give away your center, and you took your time. You lost it here”—he points to a square in the middle—“with your knight.” The Master gives me a three-minute chess lesson, reenacting the middle of our game as if on videotape.

“How can you remember my moves?” I ask.

“I can remember the sequence of almost every game I play that day,” he answers. “If I feel like it. Sometimes someone will play illogically, and it’s hard to remember the sequence. But most games follow the same patterns. Sometimes I write all the interesting games down at the end of the day. I’m vaguely considering writing a book.”

The Chess Master leans back, not as fidgety without the crowd. He delves into some leftover pork-fried rice and chats about the Fischer/Spassky match. Rice kernels fly everywhere. “The Fischer match helped business tremendously,” he says. “There’s never been a chess player like him—especially an American. This fall was the busiest I’ve had in years.”

At the side of his table is a newsletter. He has been printing an analysis of the Fischer/Spassky matches and selling copies for a dollar. He rambles on about Fischer. The genius of Fischer. The integrity of Fischer. The honesty. The mystique.

“Once I had a dream in the mid-1970s that I attended a party with Fischer,” he remembers. “I challenged him to a game, and he didn’t want to play me. To this day I wonder if it was because he was afraid—or because I was beneath him.” He pauses. “I think about that dream a lot.”

* * *

I visit Murray Turnbull again after Columbus Day. The weather has depleted the pedestrian force, giving him time to chat. He tells of falling in love with chess, as if he were talking about a woman: In upstate New York, 1960, a tornado swept through his family’s rural neighborhood. He had played outside in the forest every day as a child, then the tornado knocked down many trees. His mother wouldn’t let him out. A neighbor named Chris Lubahn introduced Murray to chess because they had nothing else to do. Murray had just turned 11.

In high school he fell in with a group of kids who loved chess, and they played incessantly, during lunch and all recesses. Murray joined the school’s chess team and honed his skills. He studied from 1967 to 1970 at Harvard University, where his father is a professor emeritus in the School of Applied Science. Senior year, Murray dropped out and moved to California. He became a “homeless hippie” for a couple of years.

My eyes widen. “You studied at Harvard?” I ask. “You were homeless?”

“I just didn’t feel like continuing school,” he says. “I was never interested in the corporation route mapped out by my parents. I’ve had many a disagreement with them, but they’re aware I didn’t function well in a business environment. They love me. I see them almost every weekend. Sometimes my father even stops by the table to say hello. This is perfect for me—I like working outside. The only tough part of being homeless was the rootlessness of it all. Now I have a place.”

He sighs and talks about tournaments he played in—the Massachusetts Open, the Newton Open, the Greater Boston Open—and a stint on the U.S. Amateur Championship Team from 1984 to 1988. “It’s such a great game,” he says with a smile. “There’s no luck involved. You can test a conclusion to its limits whether it’s good or bad. In politics or in other arenas, there isn’t the same ‘yes or no’ finality; in chess, there is.”

He tells me his favorite anecdote: The Boston Globe’s chess writer, Harold Dondis, brought a young friend to play. The Master used a defense created by British champion Nigel Short, but his opponent picked it apart and mated him. Murray had used all of his time, while the ringer had spent hardly any of his. “So after it was over, Harold says, ‘Murray, I’d like you to meet Nigel Short.’ I couldn’t believe it!” The Master is in hysterics.

Murray Turnbull may be eccentric, but he holds no illusions about himself. He strives to be the Chess Master. That’s all. He plays every day (weather permitting), seven days a week, from the beginning of April to the end of October. Does he think he’s a prisoner of the game?

“Everyone is a prisoner of something,” he says. “Being a prisoner of chess isn’t bad. I’m my own boss. There’s truth and justice, no ambiguity. I play so many games that each square has its own personality. I can look at that square,” he points to the right corner, “and remember a mate I had there in 1987. I can play blindfolded and see the board as if it were in front of me.”

In Murray’s decade in Harvard Square he has seen the smaller businesses vanish and the street performers and crazies flourish. “They don’t even respect me,” he says icily. “One guitarist sets up 20 feet away. He just has no grasp of chess or its culture. In Europe it’s a competition between nations, a substitute for war. Here it’s just a game.”

Murray associates just about everything with chess. Chess is his job, his hobby, his mistress.

“Are you married?” I ask.

“I don’t have enough to give to a relationship right now,” he says. “I work eight to 12 hours a day and barely make a blue-collar wage. Sure, I’d love to be married—especially to someone who could make money as well. But…” Then he shrugs uncomfortably.

“Why are you out here every day?” I finally ask. “Is it because you love chess, or—” “I love chess,” he interrupts. “I love being outside. I love the independence of it. That’s why I’m out here. I have a place.”

* * *

We play one last game, my final chance to beat the Chess Master. I pack the middle, my eyes searing. He moves his king to the left corner. I move my queen and bishop to attack that side. We exchange pawns. We exchange knights. He steals another pawn. Suddenly I’m in check, and my bishop’s gone, and the clock’s running down, and I’m in check again.

“Mate,” the Master says.

I laugh. I shake my head.

“You should have brought your other knight forward,” he suggests, rocking back and forth, puffing on a cigarette. “You didn’t use the left side of your board.”

I pay him six dollars, two for each of my three thrashings. We shake hands like old friends. Another person slides into my seat, ready for a beating. It’s midafternoon in the Square, and the yodeler wheels by us. “Yoodle-lay-hee-hoo,” he yells. A woman who owns a games store approaches the Chess Master. “Murray, can you still come by today at five?” she asks. He had agreed to come over and demonstrate moves. “You can either have a new set of pieces or a new time clock.”

“I’ll take the new clock,” the Master says quickly. He fidgets excitedly. “I need a new clock.”