‘Ain’t Doing Right’

After you’ve lost a beloved canine companion, you might be reluctant to adopt another–until you see what’s patiently there waiting for you.

No matter your age, being open to new love is never easy.

Photo Credit : Sharif Tarabay

Photo Credit : Sharif Tarabay

Retirement should have been an easy time for Gaylord Gale. A man who had served his country in World War II and then worked for years as the postmaster general of Stowe, Vermont, he had a tidy, modest house just down the road from our veterinary clinic in Stowe, the town in which he was born and raised, and in which his ancestors had settled more than 200 years earlier. He had his woodworking hobby and a prolific vegetable garden to tend; the problem was he didn’t have much free time to enjoy them. His wife, Thelma, suffered from end-stage emphysema, and Gaylord cared for her at home. He quietly went about performing the numerous necessary and personal tasks for her without complaint.

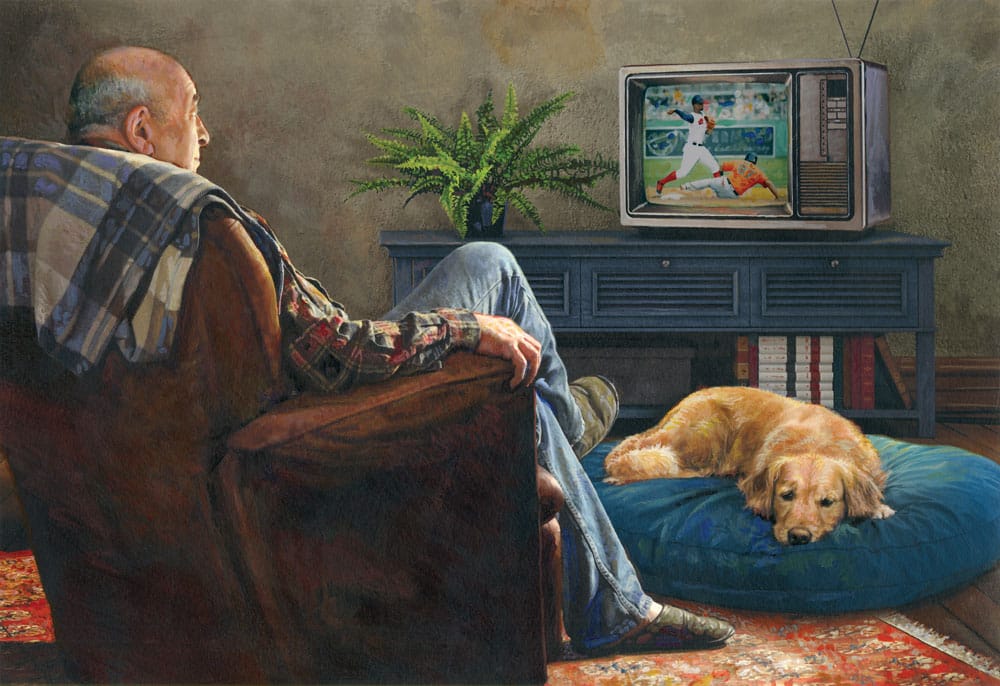

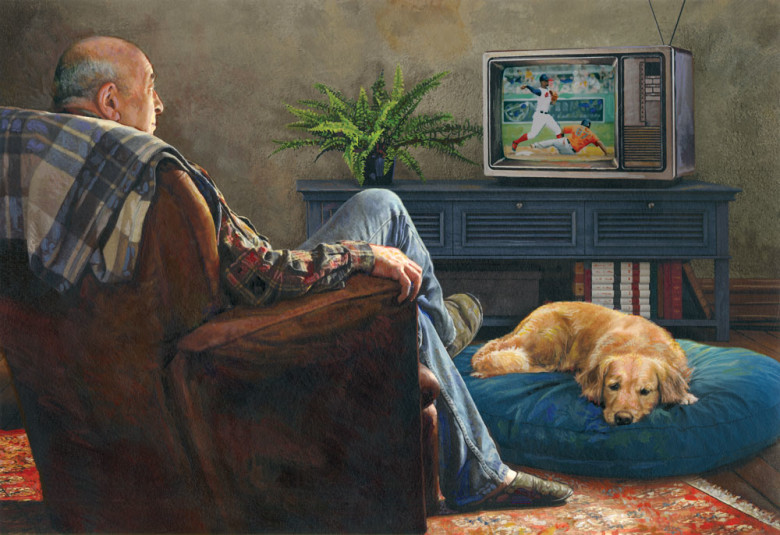

Next to his wife and their children and grandchildren, Gaylord was devoted to his dog, Valentine, a long-coated golden retriever–black Lab mix. Gaylord and Valentine were inseparable. She knew his routine intimately and accompanied him through each of his daily chores. In the morning, while Gaylord cared for Thelma, Valentine lay nearby, watching him intently. At midday, she followed at his heels as he made his way across his lawn to pick up his mail. She would wait patiently on the edge of the grass while he went to the mailbox, then fall in behind him again as he walked back to the house. In the afternoon, when Gaylord was tending his vegetable garden, Valentine would rest her graying head on her paws, her liquid brown eyes fixed on Gaylord’s stooped back as he tidied his bush beans. In the evening, she lay next to his recliner as he watched TV with Thelma after he had fixed them a modest supper. Gaylord moved through his days at a measured pace, which suited old Valentine perfectly. They were a good match, each quietly capable of great love.

When Thelma died, Gaylord’s family and neighbors rallied around him as he gradually adjusted to the gaping hole in his life. His next-door neighbor, a single mother struggling to put two boys through college, asked Gaylord for handyman advice, which he seemed happy to give. She invited him for dinner and to neighborhood cookouts. I baked a pie every so often and dropped it off for him. He’d accept it in a slightly embarrassed way, but two days later the empty, clean pie plate would show up at the door of our clinic. Gaylord’s daughter and grandchildren, who lived out of town, would come for visits, too.

This attention from family and friends, however, couldn’t match the continuous and comforting presence of Valentine, who kept Gaylord company as he slowly resumed his woodworking and gardening. But she was getting old and was suffering from epilepsy, for which my husband, Gregg, had been treating her for years.

One afternoon, Gaylord called our clinic.

“This is Gaylord Gale,” he said in his characteristically polite, almost formal way, as though we might not recognize our neighbor’s quiet voice and local pronunciation. Gregg asked how he and Valentine were doing.

“Well,” Gaylord said, “I just don’t think she’s acting quite right.” He didn’t suppose it was her epilepsy; instead he explained that she’d been slowing down and staggering, and lost her appetite. Gregg told Gaylord to bring her in. In his appointment book Gregg scribbled: 10:30: Valentine. ADR.

ADR is a veterinarian’s shorthand for “ain’t doing right.” An expression taught in veterinary school, it means an animal has a health problem that the owner doesn’t know how to accurately describe. In human terms, it’s analogous to the medical expression “failure to thrive.” The phrase simply conveys a descriptive starting point.

Gaylord looked deeply uncomfortable when he brought Valentine, then 13 years old, into the exam room. I guessed it might have brought back memories of Thelma and her medical care. He was a practical man, however. After Gregg examined Valentine, took x-rays, did blood work, and finally told him Valentine had cancer, Gaylord accepted the news stoically.

Sadly, Valentine deteriorated quickly. A week later, around mid-December, Gregg was called to Gaylord’s house to put her to sleep.

We worried about Gaylord being alone, so when a golden retriever rescue group brought a sweet 9-year-old named Amber into the clinic for an exam, Gregg got an idea. Amber had been orphaned when her elderly owner died. She might be an ideal match for Gaylord, Gregg thought. The problem was how to approach Gaylord without seeming to meddle or invade his privacy.

In February, Gregg gave it a shot.

“Well, I don’t know,” Gaylord said when Gregg called him. He sounded reluctant. Gregg didn’t want to push, but he believed Gaylord and Amber might be perfect for each other.

“How about if I just bring her over for you to meet for a few minutes?” Gregg said. “If you don’t think you’re ready, you can just say no, and I’ll understand.”

There was a long pause on the line. Finally Gaylord said, “All right, I guess I could meet her.”

Not long afterward, Gregg and Amber were climbing the steps to Gaylord’s sliding glass door. From his recliner in front of the TV, Gaylord motioned Gregg to come inside.

“This is Amber,” Gregg said. He dropped the leash and Amber, tail wagging, walked immediately to Gaylord and rested her head on his knee. Instinctively, he began to gently stroke her head.

“Well, I don’t know,” he said slowly, after a few minutes. “I guess she can stay for a while to see how it works.”

For the next two years, Amber followed Gaylord devotedly. She lay at his feet as he watched TV, strolled with him across the lawn to check his mail, accompanied him while he tended his garden, and came with him to the neighborhood cookouts.

Gaylord brought Amber into the clinic regularly for her baths and yearly physical exams. The last time he brought her in, however, he was concerned that she was having trouble walking. “She’s just not herself,” he had said when he called for the appointment. Gregg wrote in the appointment book: Amber Gale. ADR. His examination revealed that Amber’s foot was swollen, and a subsequent x-ray confirmed the worst: aggressive osteosarcoma.

In Amber’s case, amputation and chemotherapy were not viable options. Gaylord silently took her home to nurture her and keep her comfortable; a month later, Gregg had to go to Gaylord’s place to euthanize her.

Adopting an older dog always involves the risk of health problems. We knew this, and Gaylord knew it. Still, he had been through so much with Thelma and then Valentine that we felt awful for having set him up with Amber only to have him experience heartbreak and loss yet again.

A year or so passed in which we saw only Gaylord, alone, walking to his mailbox or working in his garden. Then Gregg got a call.

“Hello, Gregg, this is Gaylord Gale,” the familiar voice said. “I was wondering if you might keep your eyes open for another dog.” It couldn’t be just any dog, he said, and Gregg knew exactly what he meant. Gaylord needed a sweet, peaceful companion; the dog had to need Gaylord in return. Gregg called the local dog rescue and explained what he was looking for, and a few weeks later they brought over a 9-year-old red and white collie mix, slightly pudgy, affectionate and gentle. Her name was Pixie.

Once again, Gregg found himself knocking on Gaylord’s sliding glass door. From his recliner, Gaylord motioned for Gregg and Pixie to come in. Gregg dropped the leash and Pixie walked over to Gaylord. He thoughtfully stroked her head, his expression impossible for Gregg to read.

“Well, I don’t know,” he finally said, as much to himself as to Gregg. “I guess she can stay for a while to see how it works.” He continued stroking Pixie, who sighed contentedly, then settled at his feet.