Wicker Furniture | New England’s Gifts

Design historians usually give credit for the evolution of wicker furniture in America to a grocer named Cyrus Wakefield, who discovered a use for the strips of rattan he’d seen on the wharves in Boston.

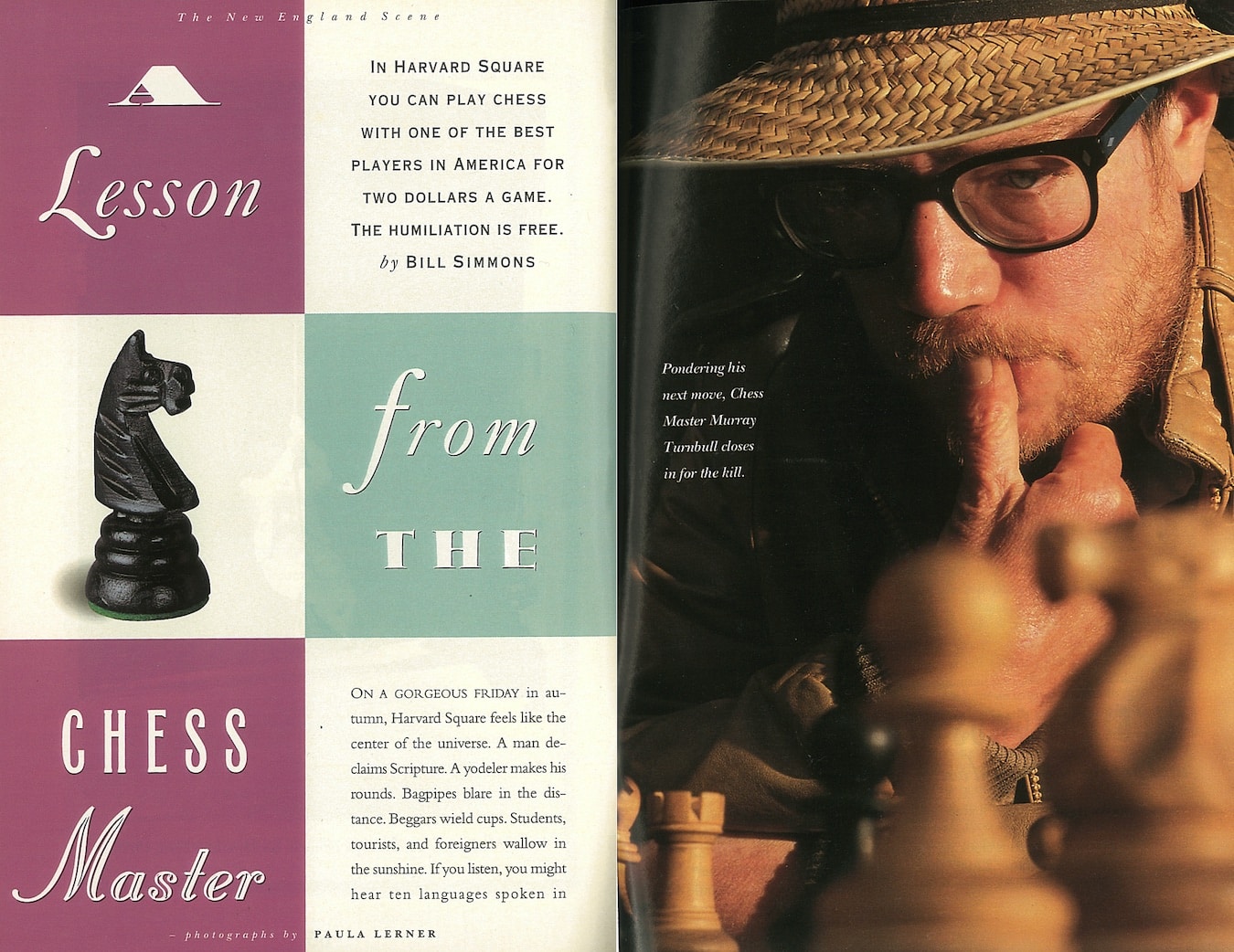

Looking out toward the nearby barns and mountains, vintage wicker rocking chairs grace the porch at the Buckmaster Inn in Shrewsbury, Vermont.

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Nonchalant, lightweight, and airy, wicker furniture charmed all of America from the end of the Civil War until the 1930s. In Victorian times it was everywhere—in parlors, on porches, in railroad buffet cars. It graced the mansions and summer houses of the wealthy as well as humbler dwellings.

Design historians usually give credit for wicker’s evolution in America to a grocer named Cyrus Wakefield, who discovered an innovative use for the strips of rattan he’d seen going to waste on the wharves in Boston. Ships bringing goods from the Far East used rattan to keep cargoes from shifting and to cushion crates of porcelain. All of it—and there was a lot—was discarded as soon as the cargo was unloaded.

Starting in the 1840s, Wakefield began experimenting, wrapping a Provincial-style rocking chair in rattan strips to give it an Oriental appearance. At the same time, he was selling the rattan itself to Boston-area chairmakers, who needed it to meet the demand for cane-seated chairs. In time, Wakefield built an empire from wicker furniture and led the world in its manufacture, with factories in three states and warehouses as far as London. He built his biggest factory in his hometown of South Reading, Massachusetts. After he donated land plus $30,000 to build a new town hall, the town voted to rename the place in his honor. Flattered, Wakefield ended up paying more than $100,000 for the stately mansard building.

There’s still quite a bit of early wicker around, but since the 1960s, the market has been flooded with reproductions from Asia, some of which have now acquired the patina of age. How to tell them apart? Reproductions tend to be lighter than old wicker pieces because the framework is made of bamboo or rattan rather than oak or other hardwoods. Collector and dealer Marla Bryer-Segal of Marblehead, Massachusetts, puts it most breezily: “If it blows over in a strong wind, it’s a reproduction.”

—“Cyrus Wakefield’s Smart Idea,” by Robert J. Pushcar, June 1997