Sunken Treasure | Sea Scallop Recipes

Making the most of a beloved bivalve in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Dawn breaks in New Bedford Harbor, home to the nation’s highest-grossing commercial fishing fleet.

Photo Credit : Nina GallantBy Jean Kerr

It’s a clear, brisk January day in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Most of the scallop boats—a fleet of about 300 vessels ranging in size from 80 to 130 feet—are in port, tied up alongside the pier, undergoing repairs and repainting, or simply waiting for the spring, when the hard work of dredging for the prized bivalve will begin in earnest. By May, and well into the summer, the fleet will be bringing in New Bedford’s gold standard: sea scallops.

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

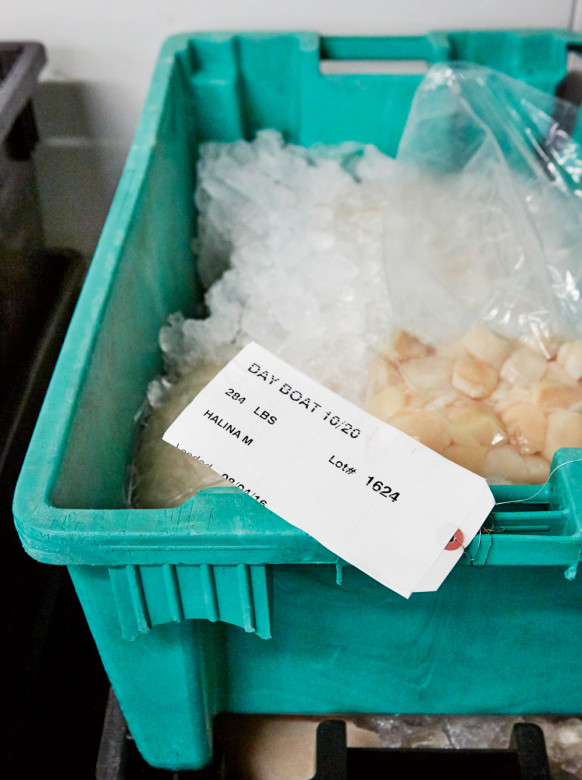

Harvesting sea scallops by dredges, which are lowered into the ocean by huge booms and raised by powerful winches, is, like most commercial fishing, physically exhausting. The scallops are deposited on deck, then loaded into heavy plastic bushel baskets and cut to release the treasured white muscle. Everything but the muscle goes overboard. The meat is packed into 50-pound cheesecloth bags and iced in the ship’s hold, where it will stay until it is off-loaded and ready for New Bedford’s seafood auction.

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

Even in winter, New Bedford is a busy place. Busy, and very, very successful. Here, in a single bountiful day, the catch can reach 500,000 pounds, and annually it reaches nearly 50 million pounds. According to port director Edward Anthes-Washburn, scallops account for about 80 percent of the fishery’s total catch, with 2015 revenue hitting $329 million. “When you figure in sales from processing and related businesses, the New Bedford fishing revenues were around $3.2 billion,” he says.

In a region where collapsing groundfish and shrimp fisheries have dominated the news, New Bedford has reigned as the highest-grossing fishing port in the U.S. for more than 15 years. As New Bedford mayor Jonathan Mitchell says, “We can truly lay claim to being the seafood capital of America.”

This prosperity has led to a renovation of New Bedford’s historic downtown, with its cobbled streets, boutiques, art galleries, and dozens of restaurants, many of which show New Bedford’s ethnic diversity to delicious advantage. The Cork, a gem of a tapas restaurant right across the street from the pier, serves seared scallops over sticky jasmine rice with a sweet soy reduction. On a Friday night at Cotali Mar, a booming Portuguese restaurant, scallops Florentine and a killer steak cooked tableside on a heated stone slab are enjoyed against a backdrop of friends toasting and joking in Portuguese. And at the “urban winery” Travessia, on Purchase Street, Marco Montez makes impressive varietal wines with grapes from both Massachusetts and California. Even with a population of nearly 100,000 souls, New Bedford feels like a close-knit community with pride in its hard-won success, its history, and its fishing fleet.

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

Had you been standing on the very same waterfront 200 years ago, you would have seen another fleet of highly profitable vessels crowding the waters. On any given day, more than 300 square-rigged whaling ships floated in this harbor, bringing the city its first wave of wealth. It was here, in 1841, that Herman Melville boarded the Acushnet and shipped out on the voyage that would inspire Moby-Dick. Whaling shaped the city’s landscape, gilding it with such displays of prosperity that Melville wrote, “Nowhere in America will you find more patrician-like houses, parks and gardens more opulent….” Whaling also shaped New Bedford’s culture, attracting crew from the Azores, Madeira, Portugal, and Cape Verde—as well as Scandinavia, Greece, and Italy—many of whom settled here. Today, some 60 percent of New Bedford residents claim Portuguese heritage.

New Bedford’s modern-day success has emerged from a close and productive partnership between fishermen and researchers like Brian Rothschild, founding dean of the University of Massachusetts School for Marine Science and Technology. Along with fellow UMass researcher Kevin Stokesbury, Rothschild pioneered some of the video monitoring techniques that allow researchers to assess the health and quality of scallop beds. He has spent his career toggling between government and academic positions, all with the goal of protecting both the oceans and the livelihoods of those who fish them. While the relationship between regulators and fishermen has, historically, been tense, Rothschild has gone about his work, applying his research with the aim of building “trust, consensus, and transparency,” he says. “Leveling with one another on what we don’t know is as important as exchanging viewpoints on what we think we know.”

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

The Quinns are one such fishing family whose livelihood has depended on this kind of collaborative fishery management. Charlie Quinn, the patriarch, began scalloping as an unpaid crew member to pay off a debt. He eventually bought his own boat and now manages a fleet of five. “He’s a hard worker. He pushes the guys,” says his son Mike, who grew up fishing during the summer and today serves as operations manager for Quinn Fisheries. Meanwhile, Mike’s cousin, Tim, is a captain in the family fleet. Their shared goal is to build a sustainable fishery “not just for the next 10 years, but for the next 100 years,” Mike says. “It’s the best seafood on the planet. You’ve got it right here, and it’s all fresh.”

LEARN MORE:

Scallops Guide | Facts, Tips, Recipes, and More

GET THE RECIPES (click on the title under the photo for the full recipe):

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant

Photo Credit : Nina Gallant