Resilience, Courage & Hope | Stories from the Yankee Archives

Of the thousands of stories Yankee has published over the years, the most compelling are the ones about people on a quest complicated by impossible obstacles.

Wil Smith

Photo Credit : Dennis Griggs/courtesy of Bowdoin CollegeOf the thousands of stories Yankee has published over the years, the most compelling are the ones about people on a quest complicated by impossible obstacles. And through perseverance—and, in no small measure, courage—they find a way to succeed. I myself have always been drawn to these stories. One of my first articles for Yankee recounted how six young men who had trekked through snow and ice to climb Maine’s highest mountain in winter became trapped on a tiny ledge by a fierce, unexpected blizzard. Though temperatures below zero made it impossible to move, all through the night they shouted hundreds of times, “Endure! Endure!”

New England does not hold the patent on resilient people who fight through the hardest of circumstances and emerge with their spirit intact, even if they have suffered pain or loss. But perhaps because our states are small, in this most compact region in the nation, it seems as if when we read about those of us who have endured, we find solace and hope for ourselves as well. We feel we know them. We know where they come from. Maybe they are no different from us; their storms were simply stronger. Because they made it, we believe we can.

In the following pages, you will meet a young boy who became separated from his family while hiking Mount Katahdin and who refused to accept any outcome but one, that he would reach safety, even as he subsisted on nothing but wild berries and water for nine days in the wilderness. In another tale, a sailor who capsized in an Atlantic storm improvises a life aboard a tiny rubber raft, bobbing helplessly in a vast sea for 76 days.

Years from now, there will be stories told about how we made it through this global pandemic, this event that tests everyone, young and old, rich and poor, in small towns and big cities. We will read about hopes dashed and lives lost—but also about heroes who showed up day after day in mask and gown to care for others, heroes who volunteered to receive experimental treatments or vaccines. We will read about how we cared for each other, for total strangers, just by staying apart.

I remember sitting in the living room of Christa McAuliffe’s mother, Grace Corrigan, as she described to me how she had looked skyward in her proudest moment, as her daughter took off in a rocket to become the first teacher in space, and then how she responded to the deepest loss imaginable. She simply refused to break. We all face challenges that test our will to carry on, or our ability to wait out the storm, or to reach that distant shore, or to slash our way through brambles until we see a cabin with a light in the window. But these stories tell us that others have done this. And we can too. —Mel Allen

The following profiles are excerpts of classic Yankee stories; links to longer versions are available here.

Stories of Resilience, Courage, and Hope

Grace Corrigan | A Mother’s Mission

Adapted from “Christa McAuliffe’s Messenger” by Mel Allen, January/February 2011

Photo Credit : Carl Tremblay

The last time most people saw Grace Corrigan, she was looking skyward, her husband, Ed, beside her, in the bitter cold of a Florida morning, January 28, 1986. When the space shuttle Challenger roared off the launch pad with six astronauts and their daughter Christa McAuliffe—a Concord, New Hampshire, high school teacher and the first private citizen selected to experience space flight—aboard, Grace was gripped with fear and pride and hope. All of those emotions tumbled out on her face in the cold, her cheeks brushed by her white fur coat, as she strained to follow the rocket. Then Mission Control announced, “Go at throttle up”—and, a heartbeat later, the sky erupted.

And now I sit facing Grace Corrigan, with Christa’s official NASA portrait on the wall behind me. “It just doesn’t seem possible that it’s 25 years. But it is,” Grace says. We’re in the living room of the home where she and her husband raised five children, in a family neighborhood in Framingham, Massachusetts. Through the picture windows her lawn bustles with birds and squirrels. I see a wall covered with photographs, so many it’s as though family albums have emptied onto the wall: Christa as a baby, as a child, in Girl Scouts, in high school, in college; Christa the young wife, the mother, the teacher; Christa in astronaut garb, the woman who swept a country off its feet.

And there’s a photo of Grace herself, giving a commencement speech at what is now Framingham State University, the school from which both mother and daughter had graduated. “The commencement speech Christa was supposed to give,” Grace says.

She’s done that so many times, speaking to thousands of teachers and children, almost within weeks of the day her daughter disappeared from her sight; writing A Journal for Christa; answering reporters’ questions on anniversaries; answering reporters’ questions when the crew of the space shuttle Columbia died in 2003 (“I’m not doing very well,” she said then) and when Barbara Morgan (Christa’s alternate for the Challenger voyage) completed her successful shuttle mission in 2007.

On this day, for example, Grace has just come home from Huntsville, Alabama, home of Space Camp, just down the road from where Christa had spent part of her training. “I haven’t even unpacked,” she says.

She returns every year to Space Camp for the special week when “Teachers of the Year” from across the country and around the world converge to explore the mysteries of space travel. “I tell them that Christa was a teacher,” she says. “That was the most important job for her. When she came back, she was going to go back to teaching. This was the thrill of a lifetime for her, but she felt it was going to focus on education and that it would get the kids excited.”

I tell her I find it remarkable that she can do this for all these years; I say I doubt I could. She laughs gently. “You know how I do it? I know Christa would say, ‘Hey, Ma, I’m not here. It’s a good message. What did I give my life for? You know, I should be there doing it. I’m not. You can do it.’” Christa’s mother smiles. “If I can help, just by carrying her message, that’s what she was striving for.” She looks at me with an expression that says, It’s clear why I do this.

Before I say good-bye, Grace tells me a story that she thinks will help me understand. “The ones I remember most are the ones where the kids are really deprived,” she says. “There was a school in New Jersey. It’s a tough, tough school. They were a little scared [about] how I would be received. And yet”—here she stops, and her eyes shine—“they were the most wonderful audience. The auditorium was packed. The kids didn’t let out a peep. The teachers had taken my book, and each grade had taken a part and done projects. I remember this part so vividly. I was talking about questions children had asked me, and in that big auditorium it was so quiet I heard a little voice: ‘She’s talking about my question!’

“When I drove away, I said, ‘Thank you, Christa, thank you.’”

∗ Epilogue:Grace Corrigan passed away at age 94 on November 8, 2018, survived by her children Christopher, Stephen, Elizabeth, and Lisa, as well as nine grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

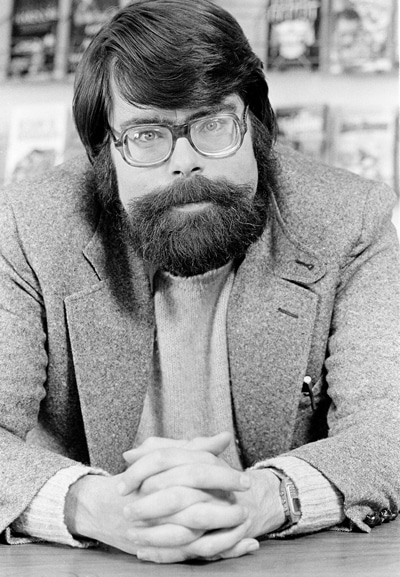

Stephen King | The Hard Way Up

Adapted from “The Man Who Writes Nightmares” by Mel Allen, March 1979

Photo Credit : AP images/Marty Reichenthal

My mother brought me and my brother [David] up (in Maine) because our father deserted the family when I was little. Home was always rented. Our outhouse was painted blue, and that’s where we contemplated the sins of life. Our well was always going dry. I’d have to lug water from a spring in another field, and even now I’m nervous about our wells.

“My mother worked the midnight shift at a bakery. I’d come home from school and have to tiptoe around so as not to wake her. Our desserts would be broken cookies from the bakery. She was a very hardheaded person when it came to success. She knew what it was like to be on her own without an education, and she was determined that David and I would go to college. ‘You’re not going to punch a time clock all your life,’ she told us. She always told us that dreams and ambitions can cause bitterness if they’re not realized, and she encouraged me to submit my writings. We both got scholarships to the University of Maine. When we were there, she’d send us $5 nearly every week for spending money. After she died, I found she had frequently gone without meals to send that money we’d so casually accepted.

“When I started Carrie I had finished my first year of teaching. When I finished it I sent it off to Bill Thompson at Doubleday, whom I’d talked to on the phone when I was in college. My wife, Tabby, and I were having a really tough time. We had our daughter, Naomi, and our son, Owen. Our phone was taken out because we couldn’t afford it. Our car was a real clunker. When the telegram came saying [Carrie] was accepted with a $2,500 advance, Tabby had to call me at school from across the street.

“Later my agent told me the paperback rights were bought for $400,000. I said, ‘You mean $40,000.’ He said, ‘No, I mean $400,000.’ I realized that meant $200,000 for me and I wouldn’t have to teach anymore. My mother was dying then, but she knew everything was going to be all right.”

∗ Epilogue: Stephen King’s books have sold over 350 million copies and inspired a number of movies and television series.

Laura Bridgman | A Revolutionary Learner

Adapted from “The Education of Laura Bridgman” by P. Bradley Nutting, October 1987

Photo Credit : Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Divison

At the age of 2, Laura Bridgman—who had been born on a farmstead near Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1829—suffered scarlet fever and was plunged into a living tomb of total darkness and silence. All she had left was a sense of touch. Public opinion everywhere agreed such persons were incapable of learning. Yet Laura ultimately surmounted her handicaps to become the first deaf-blind-mute ever to read and write—a world-famous figure and a heroine to her generation. With the help of teachers at the newly founded Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, she prepared the way for others to follow. Laura became so well known that girls on both sides of the Atlantic tied ribbon over their dolls’ eyes, imitating the green sash that always covered her own.

Laura passed on an important legacy of her own. At Perkins, she was to share rooms with a half-blind, hot-tempered young woman named Anne Sullivan. In 1880, at age 14, Anne, the daughter of poverty-stricken Irish immigrants, had talked her way out of the poorhouse and into Perkins in desperate pursuit of a decent education. Anne came to know Laura well and learned the manual alphabet so that she might spell out all the latest gossip for her older roommate. This skill would prove more useful than Anne ever imagined.

In 1886 word reached Perkins that a little girl in Alabama who had lost both sight and hearing needed a teacher. Because of her experience with Laura, Anne was keenly aware the mission was no longer impossible; she accepted the assignment. As a symbolic passing of the mantle to the next generation, Laura Bridgman sewed the clothes for the doll Anne Sullivan took south to the new student. The child’s name was Helen Keller.

∗ Epilogue: Laura Bridgman would spend much of her life at the Perkins School for the Blind, where she died at age 59 in 1889. She is buried in a cemetery in Hanover, New Hampshire, not far from where she was born.

Bill De La Rosa | ‘Be Relentless. Never Give Up.’

Adapted from “The Two Worlds of Bill De La Rosa” by Mel Allen, September/October 2016

Photo Credit : Heather Perry

I was born in a small border town known as Nogales, Arizona, but raised in Nogales, Mexico. When I was 7 years old, my family risked moving permanently to Tucson, Arizona, in search of a better future. We left everything we owned in the small motel room where I spent my childhood. When we arrived in Tucson, we had no money, no place to go, no place to call home. We slept wherever we felt safe—in our car, in alleyways, within trailer parks…. My mother [Gloria] earned a living cleaning rooms at our local Motel 6. Sometimes I would tag along and help her clean, so she could come home a little bit earlier.… In October 2009, my mother was deported from the United States to Mexico, and she was barred from returning to her home and family for 10 years.” —From Bill De La Rosa’s commencement speech at Maine’s Bowdoin College, May 28, 2016

For years Bill De La Rosa’s story stayed mostly private; few of his high school classmates, few of his Bowdoin classmates, knew what was driving him. In a heartbeat, Bill had become mother, father, cook, housekeeper, brother, nurse, tireless immigration law researcher. Bill’s older brother, Jim, graduated from high school and joined the U.S. Marines. I asked Bill how he’d managed to become his high school’s valedictorian, earn scholarships, be recruited by the best colleges—all while caring for his father and two younger siblings. Bill grew silent.

“I knew I had to stay hopeful, so we all had hope, so there’s hope also for my mom. If I don’t have hope, then she doesn’t either. The way I can give her hope is by showing her how I am in school. And when semester grades came out I’d show her and say, ‘Look, Mom.’

“I didn’t want anyone to feel sorry for me, so I just started wearing different masks. I became a different person in front of my friends, in front of teachers, in front of my dad and [my sister] Naomi. In front of my mom. In middle school, every day before class, we all had to recite what teachers called ‘The Definite Dozen.’ There were 12 rules. And I always remembered number 12. It was the last rule, and every day we had to say it out loud. Only then we could take our seats. Number 12 was ‘Be relentless. And never give up.’ That was always in the back of my mind: ‘Be relentless. Never give up.’”

On Saturday, October 17, 2015, he was the only student asked to speak at the inauguration of Bowdoin president Clayton Rose. Later, Bill would tell Teresa Toro, his high school guidance counselor, who’d helped steer him to college, “I couldn’t believe it. I marched with everyone in full garb across the campus. Bagpipes played. I kept thinking, Here’s this little boy crossing the border to a school and he doesn’t speak English, who lived in Motel San Luis, and here I am speaking at something that only happened 16 times in the history of Bowdoin. How does that happen? It must happen for a reason.”

At Bill’s commencement the following spring, a tall man in a suit stopped at his table after the ceremony. He’d listened to Bill’s speech, and now he looked at his family. “Bill will change the world,” he said. “Bill will change the world.”

∗ Epilogue: After earning master’s degrees in migration studies and criminology and criminal justice from Oxford University, Bill De La Rosa recently received a full scholarship from Oxford to pursue a doctorate in law and philosophy. His research on the plight of migrants will take place near his family in Arizona. His mother has served her 10 years’ deportation and hopes to return to the U.S. soon.

Steven Callahan | Adrift and Alone

Adapted from “Lost at Sea” by Steven Callahan, January 1986. Reprinted from Adrift: 76 Days Lost at Sea

Photo Credit : courtesy of Steven Callahan

OnJanuary 29, 1982, Steven Callahan, a boatbuilder and sailor from Maine, left the Canary Islands in his 22-foot sloop Napoleon Solo, bound for Antigua. Six days later, gale-driven waves swamped his boat. Before it sank, Callahan grabbed whatever he could reach and flung himself into a six-foot rubber raft. This became his ocean-borne home for 76 days.

March 14. I have managed to last 40 days. I’ve lasted longer than I had dreamed possible in the beginning. I’m over halfway to the Caribbean. Each day, each hardship, each moment of suffering has brought me closer to salvation. The probability of rescue, as well as of failure, continually increases. I feel like there are two poker players throwing chips into a pile. One player is rescue and the other is death. The stakes keep getting higher and higher. Somebody is going to win soon.

March 28. I feel as though I’ve been twice to hell and back. I will never last another one. I am close now. I can feel it. For days the Atlantic has been barren, but now I see a huge clump of sargassum weed riding the waves.… There are things crawling, and fishing line tangled up in it. Another bundle bobs up ahead, I grab the second, then a third, then a fourth. The ocean is thick with the weed. I pick through the vegetation for food—tiny shrimp, fish, slugs, and clicking crabs.… I’m convinced I have reached the shallower waters of the continental shelf.

April 20. The evening skies of my 75th day are smudged with clouds migrating westward. A drizzle falls, barely more than a fog, but any amount of saltless moisture causes me to jump into action. For two hours, I swing my plastic buckets through the air, collecting a pint and a half.…

Dawn of the 76th day arrives. I can’t believe the rich panorama that meets my eyes. To the south a mountainous island, lush as Eden, juts out to sea. To the north is another. Directly ahead is a flat-topped isle…. Close as I am, I’m not safe yet. A landing is bound to be treacherous…. One way or another, this voyage will end today. I hear something new. An engine! I leap up. Coming from the island, a white, sharp bow pitches forward against a wave, and then crashes down.… Three incredulous dark faces peer toward me…. It’s been almost three months since I’ve heard another human voice…. The present, past, and the future seem to fit together in some inexplicable way. I know that my struggle is over. I have never felt so humble nor so peaceful, free and at ease….

∗ Epilogue: Steven Callahan still lives in Maine, where he continues to design boats, including a life raft that could help future shipwrecked sailors survive. He served as a consultant on the 2012 movie Life of Pi, which recounts a boy’s ordeal of survival after a shipwreck.

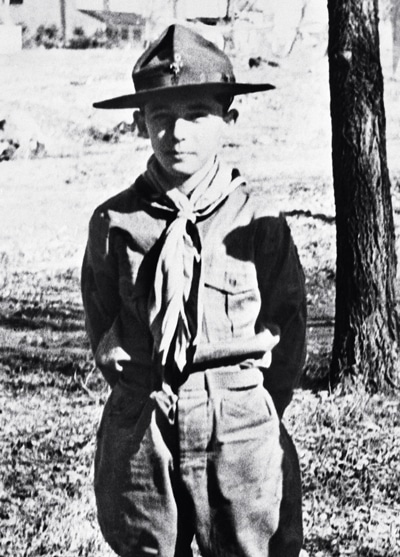

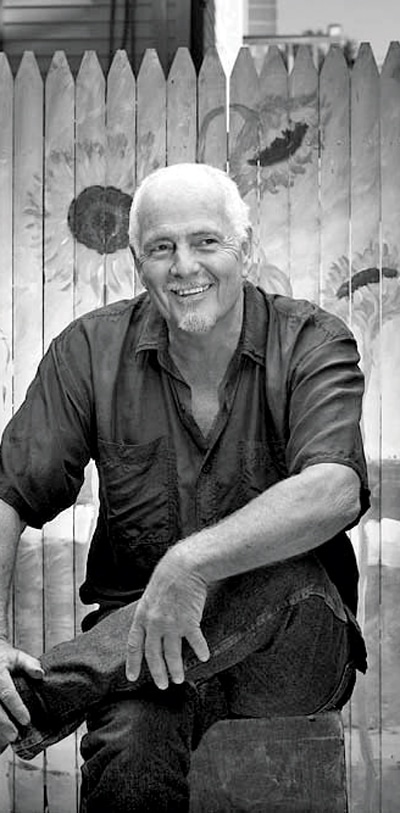

Wil Smith | The Student Who Inspired a Whole School

Adapted from “Wil Smith’s Fast Break” by Mel Allen, December 2000

Photo Credit : Dennis Griggs/courtesy of Bowdoin College

Wil Smith was unique at Bowdoin—the school’s first single father, a Navy veteran 10 years older than his classmates. He was the product of an inner-city high school attending a college in Brunswick, Maine, where more than half the students arrived from prep schools. He was one of fewer than 40 African-Americans in a student body of 1,600. He was, in the words of Dean Craig McEwen, “Bowdoin’s most remarkable student in memory.”

At the time he applied to Bowdoin, Wil was at a professional and personal crossroads. He had served seven years in the Navy and was due to re-enlist. But the Navy meant six months overseas every year, and by then he was a father to a baby girl, Olivia. He’d met Olivia’s mother in Portland after returning from overseas duty. She gave birth in May of 1995. The relationship broke up and the baby lived with the mother, but Wil got Olivia every Thursday and kept her until Monday. “No matter how untimely, Olivia didn’t ask to be here,” Wil says. “I can’t imagine a life without her.”

He sent a hastily written application to Bowdoin, and Bowdoin took a chance. His last day of active duty was April 25, 1996, the same day Olivia’s mother gave Wil full custody of his 11-month-old daughter because she didn’t feel she could raise her.

When he started college in September 1996, Olivia was 15 months old, and he had no choice but to bring her to class with him. The professors soon learned that when Olivia was sick, Wil would not be able to come. The money he saved from the Navy went faster than he could have imagined. Sometimes he didn’t eat for two or three days so he could feed Olivia. Then basketball season started.

“Coach didn’t know,” Wil says, “but I lost 17 pounds. I couldn’t sleep. I got an F in a course—Latin-American Studies—that required you to read about 20 books. I didn’t have money for the books, and I didn’t know they were on reserve in the library. I said to myself, I can’t make it. This is just too hard.” He told his adviser simply, “Things are hard for me right now.” The adviser called Betty Trout-Kelly, the assistant to the president of Multicultural Affairs and Affirmative Action for Bowdoin.

On a Sunday afternoon late in Wil’s first semester, Trout-Kelly sat him down and told him, “I know you feel you shouldn’t need this support system, but if you don’t take the help we can offer, it will be your fault. And if you don’t accept it, you won’t make it.”

For the first time Wil told her about his struggles. “The struggle to survive was so great,” says Trout-Kelly, “that he couldn’t be a student.” She called meetings—the development office, the dean of student affairs, and the president of the board came. Trout-Kelly and Dean Tim Foster telephoned Wil after the meetings. A fund from an anonymous donor would give $25,000 for Olivia’s day care. Wil would be able to move to campus housing and eat regularly with his daughter at the school. Trout-Kelly said to Wil, “I know you can do well at Bowdoin. You’ll have an opportunity to prove yourself.”

Wil replied, “Thank you. I’ll prove myself worthy.”

Wil calls his daughter “my complex joy.” He says, “All those nights when I was so tired, I was ready to quit on papers. But then I looked in on Olivia sleeping, and I turned right around and went back to my paper. She put life in perspective for me. When she was 2, I was walking her to school. It was cold, and I was holding her hand. My mind was in turmoil. I had midterms; my car had broken down; we had no money. Olivia was talking about leaves and trees. I didn’t even realize she had let go of my hand. I had taken another 10 steps without her when suddenly I turned. She said, ‘Dad, talk to me.’ She was saying in her own way, ‘Look, none of this other stuff matters.’ All she cared about was that we were there. She was glad the car had broken down. That meant we could walk to school together.”

On May 27, 2000, beneath a sparkling blue sky, Bowdoin held its graduation. Slowly Robert H. Edwards, Bowdoin’s president, read off the names of its more than 300 graduates. When he said, “Wil and Olivia Smith,” Wil carried Olivia in her shining blue dress to the stage. There was a great roar, and everyone—students, faculty, and parents—stood and cheered.

∗ Epilogue: Wil Smith’s story received national attention, with Wil and Olivia appearing on Oprah and The Today Show. After earning a degree from the University of Maine School of Law, Wil returned to Bowdoin to become the associate dean of multicultural student programs. In 2012, not long after he was diagnosed with colon cancer, he and Olivia shared their remarkable story once again, on NPR’s Story Corps. He passed away three years later at the age of 46.

The Bachelder Family | For Love of a Farm

Adapted from “Fire on the Farm” by Mel Allen, March/April 2007

Photo Credit : courtesy Bachelder Family

August 27, 2004. Early evening, about 6 p.m. There was still the last wagon of hay to get in, and the cleanup after milking. The farm is called Spooky View, named for the cemetery that abuts its land, and it’s one of only three dairy farms remaining in Epsom, New Hampshire, a small town east of Concord.

Inside the barn, Keith Bachelder has just finished milking his 35 cows and feeding an equal number of heifers. Keith owns the cows, having bought them from his parents seven years earlier, but everyone helps out—dad, mom, sister, brother, friends. It’s how small family farms have always made do. Outside, his father, Charles, along with cousins and friends, is throwing the last bales onto the hay elevator that trundles to the second-story loft. Charles and his wife, Ruth, bought this farm in the early 1970s when Keith was a baby. Charles is well into his 60s, and he’s spent nearly every day of his life on farms.

On this summer evening Keith has just finished milking and Charles is throwing the last bale onto the elevator, which is overheating, though nobody knows it. He looks up and sees the flames. “Fire!” he yells, and then everyone starts running for the animals.

The barn seems to fill with people pulling and tugging at the cows until all but one were out. Firemen from 13 towns come screaming up Center Hill Road, but the flames feed on that hay and tear through the woodwork until there is nothing left but mounds of ashes.

The finances of a small farm are always precarious, and Ruth and Charles and Keith had not increased their insurance over the years to keep up with what it would cost to rebuild. The animals were safe, but Spooky View Farm seemed destined to become one more small-print item in the papers announcing one more auction.

Then the story took a twist. Epsom’s fire chief, Stewart Yeaton, is also a dairy farmer, and he told the Bachelders the cows would go to his barn a few miles away, and, in the dark, the air thick with smoke, everyone around who had a livestock trailer drove to the pasture and loaded up the animals. Before dawn, Keith and Charles drove over to the Yeaton farm and milked their cows.

Here’s what happened next: Farmers from Pembroke, Bedford, and Contoocook delivered hay. All the local stores sprouted donation cans and people filled them up. Keith continued to wake at 4 each morning to drive to the Yeatons’ to do the milking and to soothe his cows while emerging from his own shock. “I didn’t know I was going to rebuild,” Keith says. But it was as though everyone willed him to. People brought supplies, lent their expertise and muscle. A local company brought a crane and put up rafters. A neighbor came by with a loader and another with gravel to level the land. “People just came to help from everywhere,” Ruth says. Slowly the new barn took shape on the land.

For a year and a half, the family missed their cows, as if they, too, were family. On February 11, 2006, the first truckload of cows left the Yeaton farm to come home to their new barn. “We were so happy,” Ruth says. “We opened the gate and they came running.” They put a sign out front: “Cows Are Home.”

∗ Epilogue: The Bachelder family still owns Spooky View Farm, which remains a working dairy farm.

Barney Roberg | ‘If You Give Up, You’re a Dead Man’

Adapted from “Barney Roberg’s Impossible Choice” by L. Michael McCartney, May 1980, and “Survivors” by Jim Collins, May 1992

Photo Credit : courtesy of L. Michael McCartney

In the fall of 1956, logger Barney Roberg was working alone in the woods near Patten, Maine, seven miles from the nearest help. The enormous white pine he was cutting kicked back the stump and pinned him, bleeding, to another tree. It was impossible to use his chainsaw to cut the tree in such a way to free himself. “Nobody knew exactly where I was, and I knew nobody’d even miss me until nightfall,” he recalled, “so it was pretty clear right from the start that I’d bleed to death if I just waited for help. I just kept telling myself, ‘Barney, you can’t give up. If you give up, you’re a dead man, no two ways about it.’ I had to stop and think a long time about what to do next.”

What he did next was cut his leg off. Then he tied a tourniquet around his stump and crawled two miles to his jeep. It took him four hours. Managing somehow to operate the gas and clutch pedals with only one foot, he drove himself out of the woods and found help. Eight weeks later he was back at work, driving a bulldozer.

“I was in the hospital for about seven weeks. And for a long time they didn’t know whether I was going to live or not. The doctor said the only chance I had—and it was slim—was for him to amputate the rest of my leg above the knee. I said, ‘Listen here, doc. I done all the cutting on that leg that’s going to be done. I got it trimmed up just the way I want it. Now you leave it alone.’ Am I planning on retiring soon? Never. The old Reaper’s going to be the one who retires Barney Roberg, and he’s going to have a tough enough job doing that.”

∗ Epilogue: Barney Roberg did indeed live a good long life, passing away at age 85 in 2001.

Donn Fendler | ‘A Will to Live’

Adapted from “Survivors” by Jim Collins, May 1992

Photo Credit : AP Images

Back in the summer of 1939, Donn Fendler, age 12, became separated from his family while hiking on Mount Katahdin. For nine days he walked through some of Maine’s most rugged country before being rescued—naked and emaciated—near a sporting camp some 30 miles distant on the East Branch of the Penobscot River. As he recalled: “Three things helped get me through it: First I prayed a lot, made a lot of bargains, like promising to wash the dishes. The second thing was my Boy Scout training, like following water downstream to a bigger stream. I lived on water and berries. And the third thing I guess you’d call a will to live.”

His story became a book, Lost on a Mountain in Maine, read by generations of Maine children. “I get hundreds of letters every year from kids—hardly a day passes when I don’t get one—and I answer every one. They say I’m kind of a legend in Maine, but I don’t feel like one. I don’t consider myself a hero or anything like that. I was just plain lucky.” On the 75th anniversary of his ordeal he told the Bangor Daily News that it took him a while to understand why his story resonated so much with Mainers. “Finally it dawned on me: Maine people are rugged people. They’re resourceful. They’re resilient. They’re outdoors people. People in Maine could relate to exactly what I was going through.”

∗ Epilogue: Donn Fendler went on to serve in World War II and Vietnam before retiring in 1978 as an Army lieutenant colonel. Maine declared July 25, 2014, “Donn Fendler Day” to commemorate the 75th anniversary of his adventure. His death in 2016 at age 90 was front-page news across the state.

Brendan Loughlin | Art as a Lifeline

Adapted from “Still Life” by Mel Allen, January 2008

Photo Credit : John Madere

In 1997 Brendan Loughlin is 57. Everything he owns fits into two canvas sacks, and he stuffs them into his daughter’s car, where at times he is forced to sleep. He moves into the basement of a friend’s home, until he finds sporadic house-sitting jobs. When he sleeps, he dreams of painting.

He works part-time at a paint store in Madison, Connecticut, and also at the Guilford Handcraft Center, registering students for classes. At night, after locking up, he secretly sleeps on the floor, slipping out before sunrise. He remains certain that he “was meant to paint.” In 1998 he moves into a one-room apartment in Guilford, telling the landlord that he’s an artist with no money, no security deposit, and no credit. The landlord takes a chance and rents him the room.

In the spring of 1999, to clear his head, he takes a bus to St. John, New Brunswick, and finds a cheap furnished room—“the kind bachelors rent for a month,” he says. He brings with him a drawing pad and pencils. “I was lying in bed,” he remembers, “sketching with a pencil, when I saw my future.” He buys chalk pastels and B-I-N, a shellac-based primer-sealer that he’d used when spray-painting cabinets. He mixes the pastels with the shellac and loves the texture, the explosion of color, how he can paint layer upon layer, the picture drying within moments. The pastels and B-I-N cost a fraction of what oils do. He trembles with excitement: “I was all by myself, nobody to talk to about it. I said, ‘I’m going to take this back. This is how I will paint.’”

In the days following 9/11, Guilford’s town green fills with American flags. Brendan thinks, We need to have balance, need to show joy, too—that we still believe. He hauls a slab of plywood, big as a refrigerator, in front of a florist shop at the edge of the green and paints sunflowers—vibrant, luxuriant sunflowers—and people drive by, honking and waving. MaryLou Fischer, who owns one of Guilford’s leading galleries, is moved by how people react to Brendan’s work, and she wants to see more. Soon the gallery’s walls are covered with Loughlins, and the people come in and buy them, one after the other.

Brendan becomes Guilford’s artistic Johnny Appleseed. Along the streets of Guilford, on shop doors and gates and fences bordering the green, Brendan plants landscapes that sprout everywhere—sky, ocean, great ripples of flowers, as if he’s thanking the town that embraced him.

So many people who own his paintings, who study with him, knew him when he lived on sardines from the food bank, when he curled up in his daughter’s car on frosty nights, when he was everyone’s eccentric local artist. He shows them every day that you can make your life a breathing canvas, and sometimes if the will is strong, you can wake up one day, paint a sunflower bursting with hope, and start over.

∗ Epilogue: Brendan Loughlin is still painting and teaching in Westbrook, Connecticut. In 2012, local author Jo Montgomery published a biography about him titled Loughlin: One Man’s Journey to Redemption Through Art.

Susan Haughwout | The Town Clerk Who Could

Adapted from “Tropical Storm Irene Will Never Be Forgotten” by Ian Aldrich, July/August 2016

Photo Credit : Ian Aldrich

On August 27, 2011, Tropical Storm Irene slammed into America’s eastern seaboard, bringing with it winds that reached 85 mph and torrential rains that dumped as much as 11 inches of water on parts of the Northeast.

Across Vermont, Irene was especially catastrophic: six deaths, more than 500 miles of roads damaged or destroyed, many towns made inaccessible for days. Of the countless unsung heroes to emerge in the state during and after Irene, town employees played some of the most crucial roles in the recovery work. Perhaps none more so than Susan Haughwout, the longtime town clerk for Wilmington, which, because it’s bisected by the Deerfield River, became one of Vermont’s hardest-hit communities.

“That night before the storm I couldn’t sleep,” she later recalled. “I was nervous. I tried to doze, but I had the Weather Channel on the whole time. I was pretty panicked. Finally, at around 5 a.m. I got out of bed. I told my husband, ‘I have to go down to the office and start moving books so they won’t be damaged by flood-waters.’ I stopped in at the fire department. I spoke to one of the men: ‘Do you think I ought to prepare for something worse than the ’38 flooding?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Yes.’”

For nearly two hours, in the midst of heavy rains and rising waters, Haughwout and a small crew of volunteers schlepped documents from the town hall’s first-floor vault to the building’s second floor, piling up office chairs with boxes and then rolling them onto an elevator. Not everything was saved, of course, but by her own estimate, Haughwout and her team saved some 95 percent of the town’s records.

“As we worked, I’d go outside to check the river,” she said. “A couple of times I came back inside and told the group, ‘It’s getting really bad. We’d better go.’ And they just said, ‘No, we’re not done yet.’ At one point I went out and saw that the water had breached the bridge and all this stuff was pouring over it—dumpsters, propane tanks, logs—just flying past.”

The crew worked right up until they couldn’t. To have done anything less or, worse, nothing at all, would have been detrimental to the town, said Haughwout, who was forced to abandon her car in order to escape to safety. “The buying and selling and financing of real estate would have come to a halt. If you can’t provide title, you can’t do business. You gotta have it. These are critical documents for the economy of any Vermont town.”

∗ Epilogue: On May 1, Susan Haughwout, a 2014 recipient of the Vermont Municipal Clerks and Treasurers Association’s Town Clerk of the Year award, retired as Wilmington’s town clerk after 25 years.

Connie Small | Keeping the Light Burning

Adapted from “Keeper of the Lighthouse Keeper” by Mel Allen, August 1982

Photo Credit : courtesy of lighthousedigest.com

Connie Small was 19 when her husband, Elson, became the lighthouse keeper at Maine’s Lubec Channel Lighthouse in 1920. The first time she saw her new home, surrounded by seemingly infinite ocean, her heart sank. She would first have to climb a tall iron ladder, and heights frightened her. She said, “I can’t climb up there.” Elson said, “You can, I’ll be right behind you. Just look up, never look down.” She would always say she followed those words for the rest of her life.

For the next 28 years, she lived in some of the most remote lighthouse stations in the country. After Lubec she lived on Avery’s Rock, three miles out in Machias Bay. There was only a half-acre of boulders and a wooden plank leading from the house to the boat slip. No phone, no electricity. She saw only Elson, and at night, while she knitted socks or sewed quilts or clothes, she’d twist the radio dial hoping to hear another voice, however faint.

She told me about the time she blistered the skin off her hands when Elson was out on the sea and the bell broke down during a storm. “I untied the ropes we used to ring the bell by hand when we saluted the lighthouse tender. I pulled all night. I knew Elson was out there.” Once, while winching the boat onto the slip she caught her arm under the clamper, crushing it beneath the cogs. “I walked the floor all night,” she told me. “Next day Elson got me to shore. I had to take the mail team nine miles to Machias while Elson returned to the light.”

When I saw Connie Small, she was living in a tiny apartment in Kittery, Maine. Elson had died. She still rose at sunrise. When fog rolled in, she would wake with a start. “There’s always the feeling that we have to get the bell going,” she said. “That there’s someone out there who needs the bell.”

∗ Epilogue: Connie Small wrote a best-selling memoir, The Lighthouse Keeper’s Wife, and gave nearly 600 lectures on lighthouse life before she died in 2005 at the age of 103.