Race to the Ballot Box | The Evolution of Midnight Voting in Dixville Notch, New Hampshire

When the citizens of three tiny New Hampshire communities gather at midnight to cast their votes, more than politics is at stake.

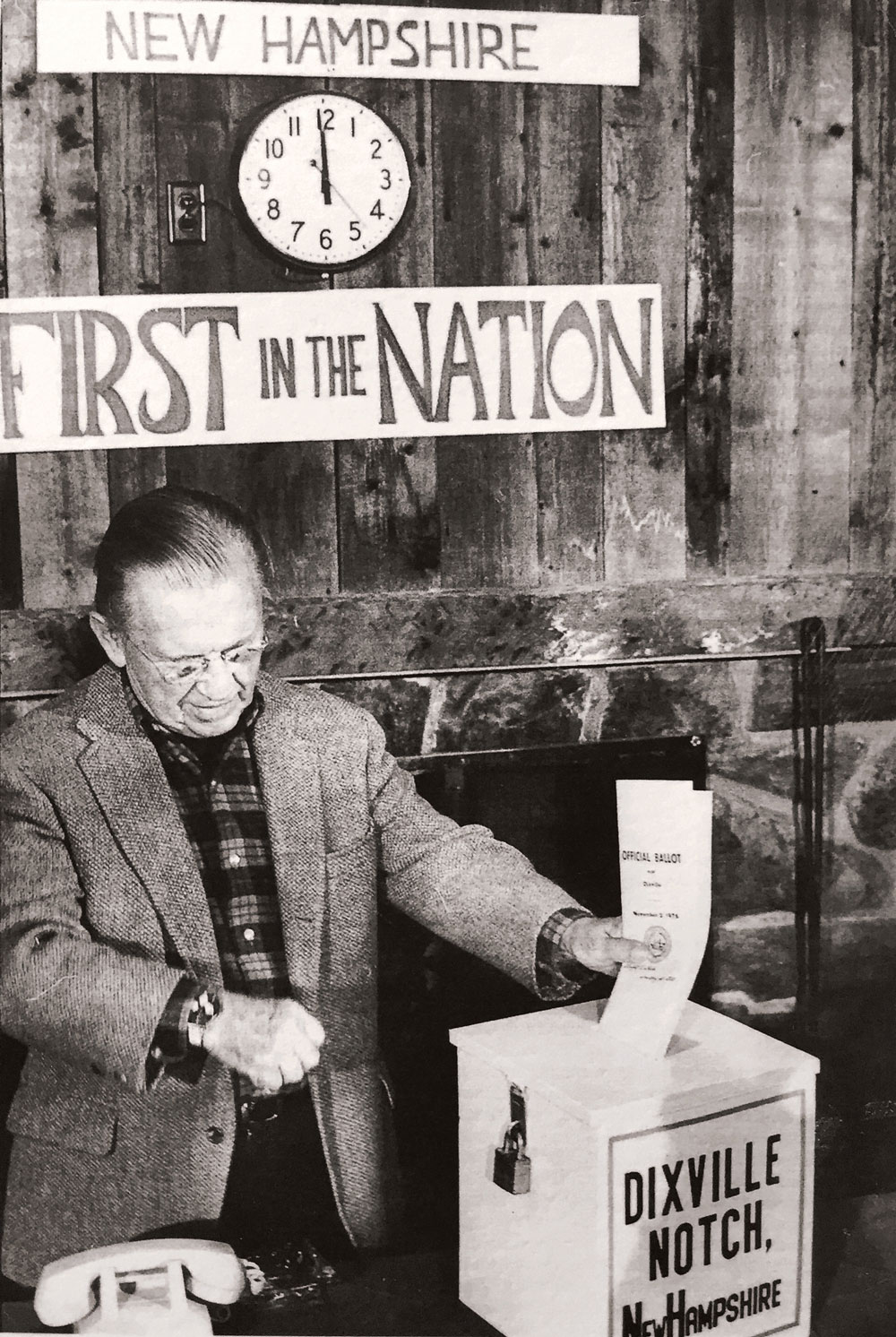

Although it wasn’t the first

New Hampshire community to conduct midnight voting, Dixville Notch became the most famous for it. The man behind it was Neil Tillotson, rubber magnate and owner of The Balsams resort. As he did over the course of 11 presidential cycles, Tillotson, pictured here in 1976, cast the unincorporated area’s first vote.

Photo Credit : NH Union Leader & Sunday News/unionleader.com

In the summer of 1959, an Associated Press reporter approached Neil Tillotson, the owner of The Balsams, a 19th-century grand resort in an unincorporated northern New Hampshire territory known as Dixville Notch, about the state’s upcoming presidential primary. For the past several election cycles, journalists had tripped over themselves as they traipsed around the state trying to nail down which community could claim first-to-vote status. Getting the news out wasn’t any easier. Few small towns had enough telephones for reporters to broadcast the results back to their papers. It was pandemonium, the AP man told Tillotson, and the media wanted clarity.

In The Balsams, a sprawling 232-room resort that basically is Dixville Notch, journalists had found the center point they were looking for. The hotel had space to accommodate them, only a handful of voting residents to wait for, and, because the property had its own telephone company, plenty of phones.

“If you’re interested in trying to be first at midnight to vote, we’ll cover it,” the journalist told Tillotson.

It was just the kind of prestigious anchor point Tillotson needed. For five long years he’d struggled to gain traction as a hotel owner. A native Vermonter and high-school dropout, Tillotson had made millions in the rubber business as the inventor of the latex glove and the party balloon. But in 1954, in “a fit of middle-aged sentimentality,” as he later said, the 56-year-old businessman had bought the resort because its property included land that his late grandmother, a full-blooded Abenaki Indian, had once lived on.

At the stroke of midnight, on March 8, 1960, Dixville’s five voters all cast their ballots for Richard M. Nixon. As he would do for the next four decades, Tillotson cast the first vote. Every four years after that, Dixville became the most talked-about small community in America. Reporters and politicians flocked to The Balsams like geese. Securing that first victory in the nation’s first primary was important. Or felt important, even if it meant getting a little silly.

In 1968 Michigan governor George Romney announced his candidacy for president on the resort’s grounds, then celebrated by hoisting his wife onto a 700-pound elephant named Popsicle. Senator Edward M. Kennedy surprised a couple getting married at the hotel with a bouquet of flowers in 1980. Eight years later, Alexander Haig arrived in Dixville by helicopter immediately after declaring his run for the White House. “As Dixville goes, so goes America,” he pronounced.Unfortunately for Haig, he was right. Dixville, and the Republican Party, opted for George H. W. Bush as their nominee.

By the 1990s, primary night at The Balsams packed all the splendor of an inauguration. Satellite trucks jammed the parking lot, while 100 journalists crowded outside the wood-paneled Ballot Room. The whole endeavor—the multihour run-up to the minute-long event, the international coverage, the grand showing of the final results on a big white board, the party that followed—might have struck outsiders as more showbiz than democracy. But to those who were at the heart of it, it was something else entirely.

“Those few moments before midnight, when everyone is standing in their voting booths and everything is quiet, even though there are hundreds of people around you—the anticipation is extraordinary,” says Steve Barba, The Balsams’ former president and managing partner, who for more than 40 years organized the hotel’s midnight voting. “Here’s a little town in America conducting its own elections to choose the person who’s going to be the most powerful person in the world. Without armed guards, without foreign observers, and doing it to the letter of the law. It was hard not to feel pride and patriotism.”

But Dixville hasn’t always had a monopoly on midnight voting. With The Balsams now shuttered and in the early stages of an expansive renovation, its midnight voting has moved to the nearby Hale House, the former private home of one of the hotel’s early owners. The property’s current owner, developer Les Otten, is determined to keep the tradition going—but as New Hampshire gears up to celebrate the primary’s centennial, other communities hope to grab a little of that Dixville spotlight.

—

![Friendly competition or a rekindling of its history? For Millsfield, New Hampshire, the town’s scheduled midnight voting, last done in 1952, is a little bit of both. “[In Dixville] there’s a history you can see and touch,” says Wayne Urso, a Millsfield selectman, photographed here at the Log Haven Restaurant & Lounge, where the community’s voting will take place. “This time around we’re trying to leave some history behind.”](https://newengland.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Wayne-Urso.jpg)

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

As he’s prone to do, Wayne Urso is making a point. Interspersed in his story–telling is a hearty laugh that resembles a wheeze, as though he’s desperate for air. It’s a late-July day, and Urso, a 59-year-old retired computer scientist, has slowed his Volkswagen Passat to a stop near the Sweatt pig farm on Route 26 in Millsfield, New Hampshire.

“This is where we used to vote,” he says, pointing to a large white farmhouse. “We’d gather in Etta’s kitchen, she’d bring out a plate of chocolate-chip cookies, and then we’d take turns filling out our ballots on her washing machine.”

The informality of the whole event was possible because there were only 20 or so voters, and Etta’s kitchen was the closest thing that Millsfield, an un-incorporated area 12 miles south of Dixville Notch, had to a town hall.

“And that’s how we did it, and everyone was fine with it,” Urso says, picking up his story. “But what they need in a place like Concord or Manchesterisn’t really needed in a place like Millsfield. And one day a state poll inspector comes and starts taking measurements in the drive for handicapped parking. There wasn’t enough space.

“Then he walked into Etta’s home and asked to see where people voted, and she pointed to the washing machine. ‘You can’t vote there,’ he said. ‘There’s not enough space.’ So Etta said we could do it in her bathroom. Out came the tape measure again, and like before, the inspector said it wasn’t up to code. I thought Etta was going to lose it: ‘Not enough space for a wheelchair!’”

Here, Urso lets out a big laugh. “Now, the only person in town who was handicapped was Etta herself. She glared at him. ‘You think I can’t get into my own bathroom!’ she yelled.”

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

Urso, who’s stocky, with a sweep of thinning salt-and-pepper hair, speaks in the enthusiastic tones of a man accustomed to crossing the finish line of whatever project he’s taken on. A Millsfield selectman and the closest thing his community has to a local historian, Urso is conveying the tale about Etta’s polling station as part of the larger story of Millsfield’s voting history. It’s one that includes a curious twist: In the 1952 presidential general election, the community’s seven registered voters turned out to the home of Genevieve Annis, and at midnight, under kerosene lamps, cast their ballots.

Little is known about how Millsfield’s midnight voting came to be, or why it stopped. Its only documentation comes from a 1952 Time magazine piece that came out shortly after the election. It’s one of the reasons why Urso has spent the past two years spearheading a return to midnight voting.

“Dixville has the Ballot Room and the voting booths,” Urso says. “There’s a history you can see and touch. There’s nothing here. We just know it was done. And unless you point to the Time article, nobody believes you. This time around, we’re trying to leave some history behind.”

But in reaching back for that history, Millsfield has had to step into a 21st century far removed from those early, simpler days in Etta’s kitchen. The town has had to build actual voting booths. A TTY line for the hearing-impaired has been installed, even though none of Millsfield’s residents is deaf. So has a handicapped-accessible voting station, just in case it’s needed. There’s also the matter of the crush of press Urso is bracing for.

During his tour of the town, Urso pays a visit to the Log Haven Restaurant & Lounge. For a one-road community, Log Haven is a surprisingly large place, with high, wood-paneled walls that give it all the ambience of a spacious lodge. Urso proudly points to the corner of the main room, where above a small stage a sign hangs between the U.S. and New Hampshire flags. “First in the Nation Vote” it says.

A rekindling of a past tradition may be part of Millsfield’s push to return to midnight voting, but it’s not the sole driving force. As Urso maps out how election night will play out, it’s hard not to detect a sense of friendly competition in his tone. Especially when talk circles back to Dixville. After leaving Log Haven, Urso heads 10 miles north to The Balsams, where a high chain-link fence borders the rambling, red-roofed building. A few out-of-state tourists have hopped off their motorcycles and are clicking photos of the hotel, which sits on the landscape like an abandoned ship.

“A legitimate voting district needs election officials,” Urso says. “Three selectmen, a town clerk, supervisors of the checklist, a moderator. They say they’re going to hold the primary in Dixville, and we hope they do, but as I understand it, there are only two registered voters. How do you run an election with only two voters? Everyone seems to focus on claims that Dixville and The Balsams will be ready.” Urso smiles, but holds back from laughing. “It seems unlikely.”

—

Photo Credit : NH Union Leader & Sunday News/unionleader.com

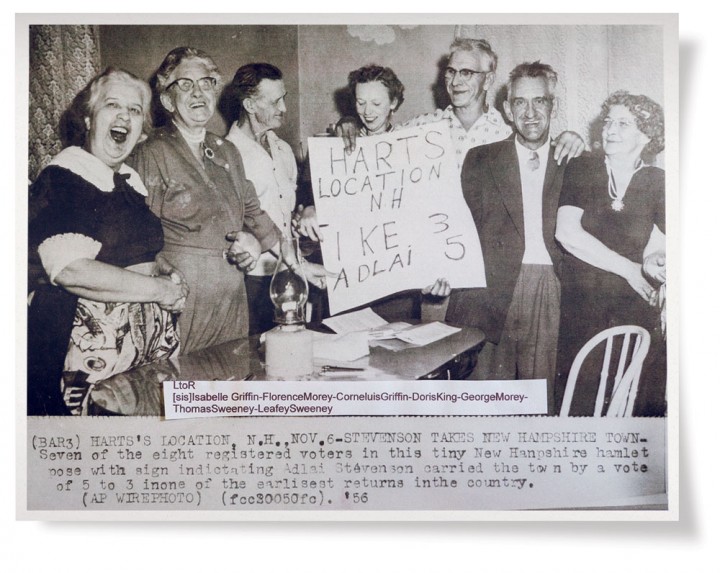

The town office in Hart’s Location is about as modest a structure as one might expect from a remote community of 41 residents in New Hampshire’s White Mountains—one that managed to go without electricity until 1970. A pair of retired Appalachian Mountain Club log cabins joined together, the building lacks plumbing or any kind of excess space. Come Town Meeting time, tables and chairs are rearranged in front of the town clerk’s desk to accommodate the session.

Hart’s is a model for what a reprised midnight-voting tradition can look like. What began in 1948 as a way to accommodate the town’s railroad workers, who couldn’t make it to the polling station during the day, quickly morphed into an event that drew reporters from around the country. On the walls of the town office hang framed black-and-white pictures that showcase its history. In one 1956 print, seven grinning residents hold up a sign that says, “Ike 3, Adlai 5.”

But the practicality that gave early voting its birth soon collided with the accompanying media circus, and in 1964 fed-up residents reverted to regular polling hours. “One of the legends is that an old geezer complained that he couldn’t go to the outhouse without some reporter following him,” says Mark Dindorf, a longtime resident and chairman of the selectboard.

Faded memories of those earlier hassles and a greater appreciation for the publicity that midnight voting could bring prompted Hart’s to return to it in 1996. If you’ve stayed up late enough on election night for the Dixville results, you’ve probably heard Hart’s Location’s name. Its tally is always reported second, which bothers residents only mildly.

“I remember being on the phone with New Hampshire Public Radio and CNN to announce our results, and I was put on hold until they had the Dixville numbers,” says Ed Butler, the planning-board chairman, who, with his partner, Les Schoof, owns The Notchland Inn. He lets out a friendly sigh and smiles: “It’s what the media and marketing people created. It’s the place that has the first vote, and that will probably be true 10 years after it no longer has the vote.”

And yet Hart’s hasn’t been completely overlooked. Candidates visit—Dennis Kucinich had a vegan Thanksgiving at The Notchland in 2004—and a mix of international and domestic press roll through periodically. A Japanese film crew spent a month in Hart’s making a documentary about its vote. “We were treated like the indigenous people of New Hampshire,” Butler cracks. “Shovel off your roof; now split some wood; okay, clear your car.”

Midnight voting can work only in a small town like Hart’s because voting takes a matter of minutes; nobody has to wait hours for the final results. But that same tiny size also presents challenges for those who make it happen. Everyone in town has to be on board for the vote. One vengeful or forgetful resident, and the polls have to stay open until everyone is accounted for. It’s why, a month before the election, Hart’s residents receive a form letter that reminds them of the election and asks them to let the town know how or if they plan to participate. On voting night they’re asked to be at the town office no later than 11:30 p.m.

Have there been close calls? You bet. In 1996, for example, there was a last-minute scramble to fetch one resident who’d forgotten to come in. But through five primary and general election cycles, the town has had full participation. And that, Dindorf says, is bigger than any rivalry with Dixville and now, perhaps, Millsfield.

“People talk about having this battle for the first vote,” he says. “To me, the thing that matters more is that we can muster 100 percent turnout. Wouldn’t it be great if the rest of the country could do that?”

Ian Aldrich

Ian Aldrich is the Senior Features Editor at Yankee magazine, where he has worked for more for nearly two decades. As the magazine’s staff feature writer, he writes stories that delve deep into issues facing communities throughout New England. In 2019 he received gold in the reporting category at the annual City-Regional Magazine conference for his story on New England’s opioid crisis. Ian’s work has been recognized by both the Best American Sports and Best American Travel Writing anthologies. He lives with his family in Dublin, New Hampshire.

More by Ian Aldrich