The Ocean Evangelist | Underwater Photographer Brian Skerry

In capturing the drama and beauty of sea life, Maine underwater photographer Brian Skerry hopes his extraordinary images can help save the future.

Skerry dove off the coast of Acadia National Park for three days straight, letting the gray seals there grow accustomed to his presence. On the last day, just before he surfaced, “a seal approached me like a family dog inching closer to be petted … [then] stopped and allowed his body to float slowly upward into a vertical position. The seal’s flippers were perfectly crossed as if he were posing for his picture, and then he swam away.” Skerry says he thinks of his career as “a long string of extraordinary encounters with wildlife—and the more you have, the more you want to have.”

Photo Credit : Brian SkerryText by Mel Allen and Brian Skerry

Brian Skerry has come home. Having traveled to the most remote oceans on earth during the three decades he’s spent working for National Geographic, the world’s foremost underwater photographer now finds himself exploring where destiny seems to have led: the frigid depths of his native New England sea.

Skerry grew up in the central Massachusetts town of Uxbridge dreaming of exploration and discovery and adventure. When his family went on beach outings in Rhode Island and New Hampshire, he always had “a yearning to know what was under those sea waves.” And he remembers as if it were yesterday being 15 and putting on scuba gear for the first time and sinking into the deep end of the backyard swimming pool—“I felt I was Cousteau himself.” Soon after, he attended the Boston Sea Rovers dive show, where he saw the work of underwater photographers. “I had an epiphany,” he says. “I knew I wanted to be an explorer with a camera. But I didn’t know how to do that. I didn’t have anyone to guide me. My parents were mill workers. Nobody in my town did that. It was a lofty dream.”

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Here’s how he made the dream happen: He attended Worcester State College, studying photography and film. He worked on boat charters that took divers to New England wrecks, where the often murky and turbulent water taught him what would work with lighting and, more important, what would not. He researched marine life incessantly and sold his photos to magazines and newspapers, each dive adding to his craft.

In 1998, National Geographic asked famed underwater photographer Bill Curtsinger to shoot the pirate ship Whydah, which sank off Cape Cod in 1717 and whose cargo of treasure was being recovered. He declined, and asked his friend Skerry if he wanted to put in his name. Curtsinger cautioned that visibility was terrible, the ship was covered in sand, and National Geographic editors gave only one chance to newcomers. But Skerry knew his way around wrecks—and his work on the Whydah has since led to nearly 30 major National Geographic magazinefeatures, documentary films, and books such as Ocean Soul.

At first Skerry sought adventure, to be part of a mysterious, “indescribable” world unknown to most people, and to capture its breathtaking beauty. But as he witnessed firsthand the effects of climate change and overfishing and saw the lack of urgency to address them, his mission evolved. “I see the ocean dying a death of a thousand cuts,” he says. “I read a scientific paper that said 90 percent of all big fish have been taken. Coral reefs are dead or dying. I was in a unique position to reach millions of readers to give context to what the science was talking about.

“I don’t want to be the baron of doom. But you want people to care. To fall in love with these animals. To understand that every breath we take is connected to the ocean.”

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Which brings us to today, and to southern Maine, where Skerry, at age 59, lives with his wife and two daughters. Now much of his work will focus on the Gulf of Maine—going on dives off the Isles of Shoals or near Nubble Light, or making expeditions 90 miles off the coast to the little-known world of Cashes Ledge. His voice is resonant with awe when he describes what he finds there: “You see this massive kelp forest. It’s amber and crimson and burgundy, and there are codfish and lobster and pollack, and on the bottom, millions of blue mussels. It is spectacular. This could still be the future. This is one holdout, one little remnant of what it used to look like here.

“We live on a water planet and we have inflicted great harm,” Skerry adds. “I like to think it’s not too late, that with good science and storytelling we can reverse the tide and help save the future. I know we are not going to reach everybody. But if enough of us are beating the drum, it can come together. That’s my hope.”

To see additional photographs by Brian Skerry, go to brianskerry.com. There, you’ll also find information about his four-part Nat Geo television series “Secrets of the Whales,” which is set to debut on Earth Day, April 22, as well as his brand-new book of the same name.

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Essay: Brian Skerry’s Unforgettable Underwater World

Although Skerry has photographed in oceans around the world, New England’s waters hold a special place in his heart. “To make a perfect picture in my backyard is a quest for me that rivals or exceeds anything else I have ever done,” he says. “These waters soothe my soul, and I want others to benefit from that.” Increasingly now, he’ll be working in the Gulf of Maine, which stretches from Cape Cod to Atlantic Canada. One focus: the marine life in Cashes Ledge, a 22-mile-long underwater mountain range that is home to the largest and longest contiguous kelp forest in the North Atlantic. “It’s unlike anything I have ever seen in New England,” he says. And since the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than any other ocean, there is a real urgency to the project. “This is a place that is suffering greatly now. If I can bring the spotlight to that, to celebrate the things that are still here, and show how it’s changing and to look at solutions, then I will have done something good.”

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

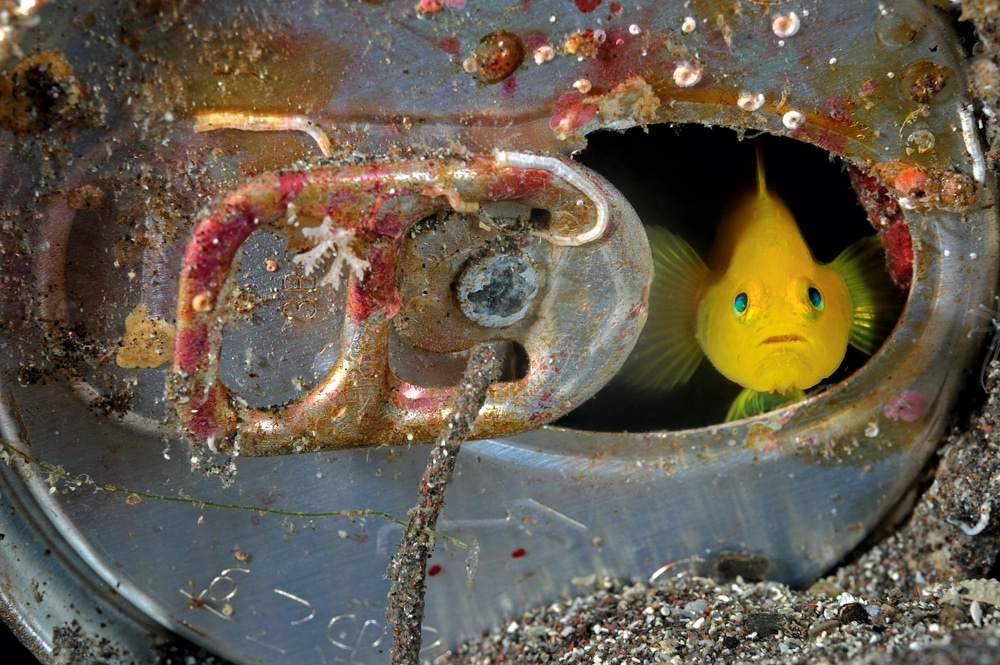

In his book Ocean Soul, Skerry writes: “Swimming over the volcanic sands of [Japan’s] Suruga Bay is like entering a fairy tale, with characters to be found around every turn.… I felt like Alice having entered the looking glass. At the depth of about 100 feet, I saw a soda can, its shiny exterior encrusted with marine growth. From inside the can I saw a flash of color and moved in for a better view…. I crawled to within a few feet of the can. From the darkness inside, a tiny yellow goby stared at me with green eyes from his pop-top window. I inched closer and watched the fish disappear and reappear like the Cheshire Cat. Thinking I might hear the goby speak at any moment, I focused my lens on the fairytale scene.”

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Although Skerry wants people to share in the wonder and beauty he finds beneaththe waves, he also wants them to be deeply troubled by how fragile the ocean ecosystem has become. While documenting the global fishing crisis for National Geographic, he photographed giant bluefin tuna—a species he calls “the thoroughbreds of the ocean” for their awesome speed and power—stacked up like cordwood on Tokyo fishing piers. That cover story came with a price: Skerry grew physically depressed by what he’d seen. He’s photographed sharks off Cape Cod, in the Bahamas, and in the Pacific, and while that work led to his book Shark, every frame he shot came with the knowledge that 100 million sharks are killed each year, many for their fins alone. But he also explores ecosystems that are all but untouched by man, and when he shows people those photos of surreal beauty—from, say, a remote ocean preserve in New Zealand, or Kingman Reef in the Central Pacific, “a diver’s holy grail”—he hopes they embrace the idea that even as we have damaged the sea, so too can we restore it. “I want my grandkids to have healthy oceans,” he says.

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry