Ripton, VT: North Branch School

I drove out on snowy spring days or in the dark evenings of early summer, to Cornwall and Salisbury and New Haven and Shoreham and Lincoln. I took off my boots in the houses of strangers and asked that they trust this place I might create, which I did not know how to create. I […]

I drove out on snowy spring days or in the dark evenings of early summer, to Cornwall and Salisbury and New Haven and Shoreham and Lincoln. I took off my boots in the houses of strangers and asked that they trust this place I might create, which I did not know how to create. I went to see a prospective student, Steve, up on North Branch Road. His mother, Tammi, told me to look for the blue trailer with cars in the yard. There were lots of junk cars–rusted, hoods up and wheels off, a Toyota truck filled with bags of trash. The yard was littered with transmission parts, hubcaps, empty soda bottles, Tonka trucks, deflated soccer balls, retired chainsaws, and piles of seasoned firewood hidden in the overgrowth of jewel-weed. A pen held an assortment of bedraggled, rain-soaked chickens and a belligerent, menacing turkey. A small garden of red and yellow snapdragons marked the way to the door.

I sat at the kitchen table with Tammi, Steve, and his father, Brian. The ashtray between us was filled with ashes and stubbed-out cigarettes. Steve was gangly, with a thin neck, acne, eyes sunk deep in bluish eye sockets, greasy hair hanging over his eyes, his silk basketball shorts hanging down over his knees.

“What subjects do you like?” I asked.

“Uh, history, I guess,” he said slowly.

“What history?”

“Um, like the Revolutionary War?”

“What about it do you like?”

“Um, it’s like, I don’t know, pretty interesting, all the battles and stuff.”

“You like sports?”

“Yeah, basketball and baseball.”

“Who’s your team?”

“The Atlanta Braves.”

“Really? Not the Sox?”

“Nah, I like the Braves.”

“The Braves are my team,” I said, smiling. “I’m from Atlanta.”

“Cool.”

“Who do you like?” I asked.

“Chipper Jones.”

“Sweet. Chipper’s awesome.”

“Yeah.”

“So how was last year in school for you?”

“Uh, not so good.” He half laughed. “The teachers didn’t like me too much. My math teacher hated me.”

“Steve didn’t do so well on his report card,” said Tammi.

“But he’s going to do better, right, Steven?” said Brian, arching an eyebrow from under the bent brim of a Patriots cap.

As I explained the school, it suddenly seemed to be a ludicrous, self-indulgent fantasy of the overly educated. Experiential learning? Piaget and constuctivism? John Keats? W. B. Yeats? I was talking to a family who scuffled by on the stray carpentry job and delivering cordwood. The chances of them wanting to send Steve were slim.

Tammi called the next day. “We’d like him to come to your school,” she said.

I looked at my growing class list. My students came from ten towns spread over the county: the eighth graders, Steve, Annie, Najat, Zoe, and Mira– each from a different school. Sophie, Tico, Nick, and Doug were seventh graders. At the last moment we added Janine, a ninth grader from Pittsford, giving us an age span from eleven to fourteen years old.

Annie, Steve, and Mira, by their accounts, had suffered through miserable seventh grade years. Annie had been relentlessly teased. Steve had failed every class but Language Arts in seventh grade and claimed that if we were to visit the middle school locker room, we could find a large dent on a metal locker door exactly in the shape of his very own head, courtesy of a posse of eighth graders who had used him as a human battering ram.

Mira had been overloaded with too much academic rigor and not enough spiritual or emotional substance. Doug was a self-described nerd, precociously intelligent, with his “Stellaphane” astronomer’s cap, too-small sweatpants pulled halfway up his calves, and copious amounts of saliva shooting from his mouth as he expounded on Star Trek or string theory. Tico could not read or write.

Annie suffered from extreme anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder. In addition, her mother told me, she was dealing with the afteraffects of an incident of sexual molestation when she was four. Sophie appeared terminally shy. Najat, according to her mother, was hesitant about plunging headfirst into the world of adolescence and still liked to play with Playmobil figures to relieve stress.

Janine’s primary home-school education had been working in a farmyard raising rabbits and tending lame horses, goats, and miniature donkeys. Zoe had been home-schooled, half-schooled or un-schooled and had spent half of a traumatic year in the local middle school. Five of the ten were receiving financial aid. Three of my students were trans-racial adoptions–from Morocco, India, and Honduras.

We came from all over the place and we were strangers. The parents did not know each other. None of them truly knew me. By enrolling their kids, they trusted my word and vision as I sketched it out in the curriculum guide. There was no instruction manual and no guarantee–just a collection of odds and ends that appeared to have, at best, only a remote chance of fitting together.

Entrusting their children to the North Branch School, a school with no defined structure, “charter” school status, or orthodoxy, at the precipitous moment when their children were entering the critical, tumultuous time of adolescence, could only be seen as an act of utter, eradicable faith.

The kids loved poetry class, and Steve seemed to love it the most. There was no possibility of a wrong answer in a poem, and for a boy who had failed virtually every class in his old middle school, this was liberating.

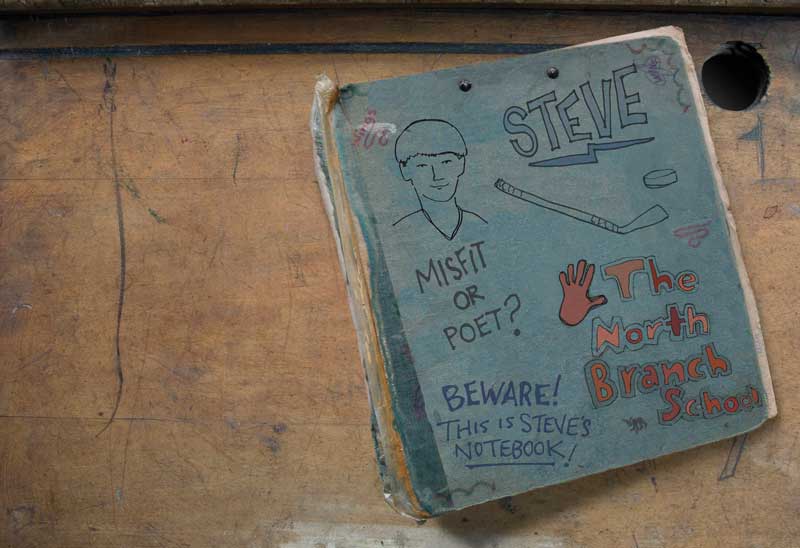

Steve had no organizational or even rudimentary study skills. His spelling was poor, his penmanship shoddy. His notebook was tattered, duct-taped, and covered with graffiti and stapled-on baseball cards. Dogeared math sheets and three-month-old assignments spilled out, displaying a sort of half-intention, half-prayer that by holding on to them he might somehow one day do them.

His responses to questions asked in class were terse, his motivation almost nonexistent. He had a hard time finding the words to express his ideas. He leaned back in his chair in a kind of dreamy torpor, with his coat wrapped around his thin shoulders and his hood pulled over his brow, his eyes moving to whoever spoke.

He walked two miles to school every day no matter the temperatures, wearing a light New England Patriots coat and no hat or gloves, his hands pulled into the sleeves. The bottoms of his red silk sweatpants were always soaked from walking through the first wet snows. He had no boots. I had given him a bag of winter clothes, but he did not wear them.

“Steve, why the hell aren’t you wearing your hat?” I asked, realizing as I said it that he would be embarrassed to wear clothes his teacher had given him.

“I don’t get cold,” he said nonchalantly.

“Tough guy, eh?”

“Oh yeah, you know it.”

Steve arrived before me every morning. No matter how assiduous I had been about locking up, he was always already inside the house. I knew why he came early: The school was a cleaner, warmer place than his home, a trailer in which there was no phone and where his father was almost always on the road driving trucks.

Most mornings he was lounging around in the school with the lights off, still wrapped in his jacket, playing games on the computer, doing a late homework assignment or resting, still half asleep, on top of the science table. He occasionally answered early morning phone calls and left scrawled messages on my desk.

One morning in December I arrived to find Steve’s footprints leading through the snow on the deck. I followed them around the building until I came to a window. Snow, leaves, and dead pine needles were ruffled where he had climbed in. I imagined him inside, dozing in the dark.

I opened the front door, kicked the snow off my boots, and turned on the lights. He was pecking away on a computer with his hood pulled tight around his face, his eyes fixed on the glowing screen. He didn’t turn around. I hoisted my backpack up onto my desk, where I saw a torn sheet of composition notebook paper, placed perfectly in the center of my desk for me to see, signed S. H. Above the initials was a six-line poem, handwritten, the neatest handwriting he’d ever proffered.

Steve knew where I was and where I was going to be, and he had met me there. It was his offering, a tentative idea, a fragile gesture saying, “Look, will you look? I have something to say.”

I held it in my hand and read it.

If I could pick a day

To spread my wings and fly

I would never break a promise

Even to this day.

I wonder if I’ll have to pay

To spread my wings and fly away.

It wasn’t much of a poem, but it stood for something magnificent, a little prayer infused with hope and tragic longing, laced with an awareness, as well, of his relative impoverishment. His words expressed a sense of foreordained limitation and his co-existence with dead ends.

At the same time the poem was about the possibility of freedom. This boy, who’d never left the state of Vermont, who’d never seen the ocean or a big city, this boy was asking for flight, praying for it, worrying what it would cost, still believing that he had wings. Then it occurred to me: The student, not the schoolmaster, had arrived early to light the woodstove. Steve had kindled the classroom with the gift of a poem.

When I stepped over the threshold, our school was already warm. When I began class that morning I told the story, a story that had never been told in our school, never had been told in the world, the story of a boy who hated school, who believed school hated him, who believed school was a place for failing, a boy whose most memorable moment in school–aside from having his head hammered into lockers–was his daily trip to the high school gym where, as he passed the Diesel Mechanics class at the Hannaford Career Center, he could catch a fleeting glimpse of his father working toward his G.E.D. It was the story of a boy who had come to a new school and there resurrected his hope of becoming a student who could spread his wings and fly.

I told them how I had found Steve’s poem on my desk.

“Do y’all realize what this means?” I asked, trying to engender some awestruck wonderment. “Do you see what is happening? Steve has written a poem. This fantastic youngster is a poet. This sorry, pants-sagging teenager has got the juice!”

“Way to go, Steve,” said Annie, in dutiful support.

“Steve wrote a poem?” said Doug, as though we had been presented with a sonnet typed by a chimp.

“Yes, he did indeed.”

“Well, can we hear it already?” asked Mira.

“You guys,” I said, ignoring her. “Steve turned this in without it being an assignment. He’s thinking, his heart is pumping, he’s got a pulse, he’s alive. He’s not just sitting brain-dead in front of a computer playing Diablo II. Well, he was this morning, but at least he wrote a poem before he did it. I’m proud of you, Steve.”

I looked him in the eyes.

“Tal!” shouted Nick. “Can we hear it!”

“Of course we can hear it. But I have to get everyone all ginned up. This is a moment of great importance.” And it was, because I wanted them all to feel and never forget what it meant for one of us to cross the threshold to become a maker.

“Okay, we’re ‘ginned up’! Or whatever you call it!” Nick clamored.

“But now we have to get our thing together, man,” I said.

“We have our thing together, man!” they shouted.

“All right, all right. You’re ginned up and we got our thing together, man. But wait, hold on, let me tell you about the time Steve Hoyt presented me and the North Branch School with his first poem he ever wrote on his own. One snowy morning I arrived in the dark classroom and it was sitting–“

“For god’s sake already, read it!”

“All right. Y’all hush. Here it is.”

And I read the poem, as delicate as a gossamer thread–small in stature, monumental in its existence.

They were silent, but looked over at Steve, who was blushing and dipping his head so that his greasy bangs hung over his face.

“I’m going to read it again,” I said, and I did, according that slight poem every bit of dignity and loving attention I could.

“So, what do you all think?”

They all raised their hands. There was no more wonderful sound and sight than that class full of hands rising up because they had all been moved, that rustling and forward-leaning, smiling excitement of hearing and seeing as though for the first time.

“I think it was really great, Steve, that you wrote that and turned it in,” said Annie.

“I’m proud of you, Steve,” said Mira. “It shows a whole other side of you.”

“It makes me want to go write a poem too,” Nick added, smiling.

“We’re waiting, Nick, we’re waiting,” I said.

“I have always thought of Steve as a grungy teen punk skateboarder,” said Doug. “But obviously he has these other aspects to his personality. It makes me think that Steve is more of a student than he has shown so far. Sometimes it seems that he doesn’t really care about school, or perhaps it’s hard for him. But a poem. I’m impressed.”

“I like what it was about, how he talked about–” Janine began, halting, not quite sure of what she knew or felt. “That part about being willing to never break a promise.”

“It’s beautiful, isn’t it?” I said.

The praise and affirmation were real, expressing their growing awareness not of ideas or facts, but of each other. That poem was the beginning of a fountain of poems, from Steve, and from all of them. That is how we got our writing community together, and how the lives of these kids, once separate and distant, began to be stitched together. That was how we began to un-govern our tongues.

Adapted from A Room for Learning: The Making of a School in Vermont by Tal Birdsey. Copyright (c) 2009 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC