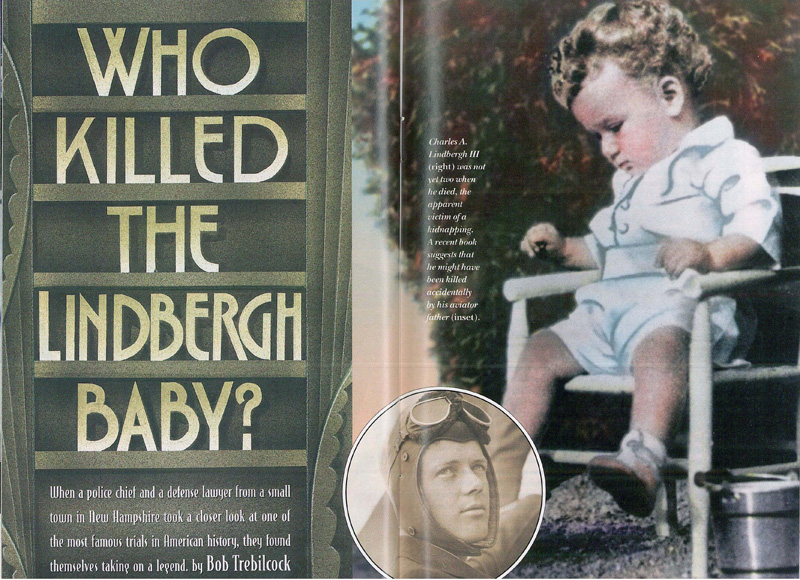

The Lindbergh Baby | Who Kidnapped and Killed Charles Lindbergh III?

When a police chief and a defense lawyer from a small town in NH took a closer look at the Lindbergh Baby kidnapping and murder case, they found themselves taking on a legend.

Who Killed the Lindbergh Baby? | Yankee Classic, 1994

Now a Yankee Classic, “Who Killed the Lindbergh Baby?” was first published in 1994.

In the summer of 1990, Gregory Ahlgren had no idea that the next three years of his life were about to be changed by a paperback book.

The 41-year-old defense attorney was sorting through boxes as he and his wife had just moved from their home in Goffstown, New Hampshire, to another in nearby Manchester. In one of the boxes Ahlgren found a 30-year old anthology about famous crimes. It included a story about one of the most notorious cases of the century, the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby. The trial had pitted Charles A. Lindbergh, an American icon, against Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a poor German carpenter who was arrested after he passed some of the Lindbergh ransom money. Although Hauptmann was executed for the crime, he maintained his innocence until the day he died. He had some prominent supporters, including the governor of New Jersey, Harold Hoffman. Time had done little to quiet the controversy.

Though faced with a mountain of work, Ahlgren read the article, which raised strong doubts about Hauptmann’s guilt. The kidnapping had taken place on March 1, 1932, in a rural New Jersey town with a two-man police force. The state police force was headed by Colonel H. Norman Schwarzkopf, a political appointee whose police experience amounted to having once worked as a department store detective and whose son would later become a hero in his own right.

Given the police limitations and Lindbergh’s stature as one of the most famous men in the world, few objected when the aviator took virtual control of the investigation — not even when he threatened to shoot any police officer who disobeyed his orders or when he used his political muscle to discourage the FBI’s involvement in the case.

That bothered Ahlgren. “What I saw in the article,” he says, “was a pattern of a person trying to obscure a crime.”

On a whim, Ahlgren mailed a copy of the story to Stephen Monier, the Goffstown chief of police and a former president of the New Hampshire Association of Chiefs of Police. He attached a note asking Monier what he thought.

Ahlgren can’t explain why he mailed Monier the article. In many respects they are polar opposites. Ahlgren, an unabashed liberal who defends the sorts of people Monier would like to lock up, was once a Democratic state representative. The 40-year-old police chief keeps an autographed photo of George Bush next to his desk.

Photo Credit : Wikimedia Commons

The pair met in a Goffstown courtroom in the late 1970s. Ahlgren had recently opened a criminal-law practice in Manchester. Monier was not only a Goffstown police officer, but also the town prosecutor.

“Greg was representing some person we’d arrested for a series of thefts,” remembers Monier. “He was very unassuming, almost a hayseed. Then he started to argue.”

The outcome? “He won,” says Monier. ”I’d like to think we’ve evened the score since then.”

A few years later Monier turned to Ahlgren when his father, a prominent politician, needed an attorney. In 1982 Robert Monier gave up his position as president of the state senate to run for governor. In the middle of the Republican primary, he was accused of conspiring to funnel bank funds into political campaigns by a bank official who had himself been arrested for embezzlement.

Ultimately the accusations proved to be false. But the damage was done. Once the front-runner, Monier lost the primary to John Sununu, who became governor. At his son’s urging, Monier hired Ahlgren to file a civil suit against the bank official for damages. Monier’s father committed suicide before the trial. Still, Ahlgren went ahead and won a $100,000 judgment for the estate. Says Monier: ” It was one of the best-tried cases I’ve ever seen.”

Despite their professional ties, Monier and Ahlgren never became social friends. Still, during courthouse breaks and the occasional lunch, they discovered that both were avid readers with eclectic tastes.

“Steve’s not your typical, single-minded cop,” says Ahlgren. ” I guess I thought maybe there was enough of a bizarre component to him that he would read the article.”

When he did, Monier, too, was troubled by Lindbergh’s involvement in the investigation. As a former juvenile officer, Marlier knew recent FBI crime statistics showed that over 70 percent of the homicides involving children under nine years old are committed by one or both parents. Yet as far as Monier could tell, neither Lindbergh was ever a suspect. It appeared the police assumed from the outset that there had been a kidnapping and then handed over the reins.

“Something’s not right here,” Monier told Ahlgren.

The two men checked out everything the local libraries had to offer on the Lindbergh case, from biographies to contemporary news accounts to the trial transcripts. Monier’s search took him to St. Anselm’s College, Ahlgren’s to the large public library in Manchester. Now and then they shared their discoveries over the phone.

“Maybe you guys’ll write a book,” Ahlgren’s wife said. At the time, they laughed at the suggestion. But they didn’t stop reading. By fall, simple curiosity had become an obsession.

“Some guys take up golf,” shrugs Monier. “We read.”

In one biography Monier learned that in January 1932, Lindbergh hid his son in a closet, then told his wife, Anne, and the child’s nanny that little Charles was missing. The women searched the house for 20 frantic minutes before Lindbergh admitted the hoax.

When the baby disappeared two months later, one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s first thoughts was that her husband had taken the child as a joke, according to a letter she wrote to her mother-in-law. Monier suspected the same thing.

“This is one strange duck,” he told Ahlgren.

By the end of 1990, the pair realized that there was an overwhelming possibility that Hauptmann was innocent. They also realized that no one had ever asked the question that would be first on the lips of a prosecutor or investigator today: Did Lindbergh do it?

They had some reservations. It wasn’t just that neither had ever written a book. Implicating an icon — even a dead icon — in the death of his child is painful.

“In 23 years in law enforcement,” says Monier, ”I’ve seen all kinds of people fall from grace, but I still don’t like it. Lindbergh was a national hero, and I think we all want to keep flying this guy across the ocean.”

Photo Credit : Wikimedia Commons

But if they were right — and they firmly believed they were right — a hero had permitted an innocent man to die in the electric chair. That, they felt, was worth exploring through the eyes of two individuals who had spent their lives in the criminal justice system.

They sketched out an outline over Monier’s kitchen table one night early in the winter of 1991. Their initial plan was to concentrate on Lindbergh’s background and his actions from the day of the kidnapping through the end of the trial.

Like a cop on the beat, Monier did the background work. He spent his nights and weekends examining the facts as if the crime had been committed in his town. Since nearly everyone associated with the case was dead or no longer talking (Anne Lindbergh has granted no public interview for years and Hauptmann’s widow, Alma, only rarely speaks to the press), he turned to the record. Nights in the library were augmented by endless calls to the archivist at the New Jersey State Police Museum near Trenton, New Jersey, where the original police files are on display.

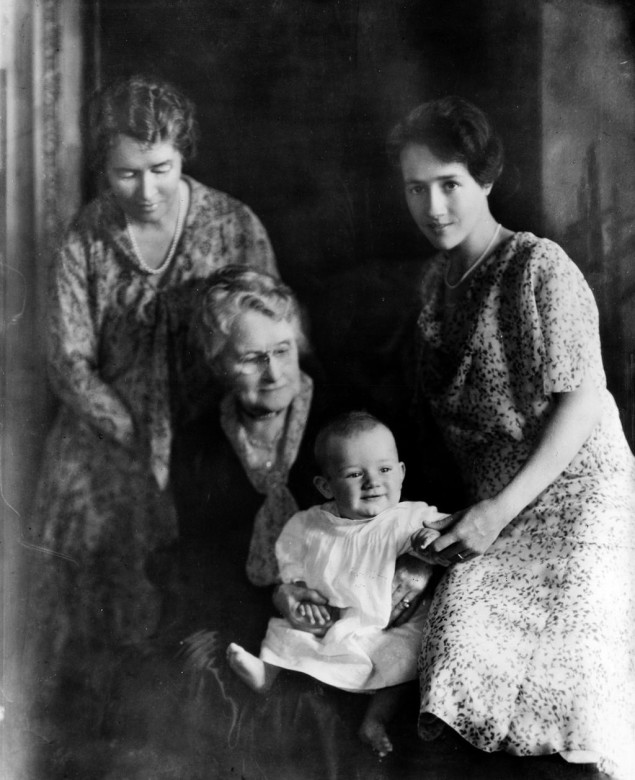

Part of what he found was expected: The Lone Eagle’s historic flight across the Atlantic, followed by a heroic return to New York; a meteoric rise in stature, climaxing with a storybook marriage to Anne Morrow, the daughter of an influential banker and ambassador.

But he also found there was another side to Lindbergh. The man behind the public mask was “a social misfit,” a rigid loner with a penchant for cruel jokes. Once during his airmail piloting days, one of Lindbergh’s roommates returned from a night on the town and took a drink from a pitcher, only to discover that Lindbergh had replaced the ice water with kerosene. The pilot nearly died. “Had it not been for the Lone Eagle flight,” a friend of Anne’s told a British writer, ” [Lindbergh] would now be in charge of a gasoline station on the outskirts of St. Louis.”

Monier was taken aback. “In life,” he says, “we tend to take a few facts and extrapolate an image of someone from that. The image I had was of a hero. But when I began reading, I was surprised to find that this was a cold, aloof guy, whom, frankly, I wouldn’t like very much.”

Monier was also surprised when he examined Lindbergh’s actions surrounding the kidnapping of his first child. Charles Augustus Lindbergh III was born on June 22, 1930. A year later, the baby was left with Anne’s parents while she and Lindbergh surveyed the Orient. The trip was cut short in October, after Anne’s father died.

Construction began on a rambling French manor house on 500 acres outside Hopewell. When the house was livable, the couple would meet there on Saturdays and remain until Monday morning, when Lindbergh left for his job in New York with Trans-Continental Air Transport and would spend the week with Anne at her mother’s estate.

That steady routine was altered on Monday, February 29,1932. The baby had a slight cold, and Lindbergh instructed Anne not to travel and expose him to the weather.

At 7:30 P.M. on Tuesday, Anne and Betty Gow, the child’s nanny, put the infant to bed. They latched two of the three sets of shutters. A set on the east side was warped and wouldn’t latch.

Twenty minutes later, Betty Gow checked on the boy one last time. Lindbergh, who didn’t want his son coddled, had given strict orders that no one was permitted in the nursery again until 10:00 P.M., when Charles was taken to the bathroom.

Around 8:25, 45 minutes later than usual, Lindbergh pulled up the driveway, honking his horn. He and Anne had dinner and then talked in the living room. Around 9:15 Lindbergh said he heard a sound, like the cracking of an orange crate falling off a chair. Anne heard nothing, and their Boston terrier never barked.

A few minutes later, Anne went to her bedroom to read. Lindbergh took a bath. At 10:00 P.M., he was in his study when the nanny asked if he had their child. Without a word, Lindbergh raced upstairs and into the nursery as Anne was coming out. “Anne,” he said, “they have stolen our baby.”

With the staff, Anne searched the house while Lindbergh drove up and down the road, flashing his headlights on the woods. They found nothing.

Upon his return, however, Lindbergh went alone into the nursery. There he found a sealed envelope in plain view on a radiator beneath a window. He ordered that no one touch it until the police arrived in order to preserve fingerprints.

The precaution was unnecessary. Inside the envelope was a ransom demand for $50,000. There were no fingerprints on the envelope or the letter. In fact, there were no prints in the nursery, not even of the Lindbergh family or staff, as if every surface in the room had been washed clean.

Minimal precautions were taken to preserve evidence outside the house, where the police found two holes in the soft ground below the nursery window with the warped shutters – the only window in the entire house that didn’t latch from the inside. In the brush they found an odd homemade ladder. Any other clues that may have existed were obliterated by the horde of police and press who trampled the grounds.

For two months the investigation went nowhere. Then on May 12, 1932, the lifeless child was found in the woods less than three miles from Lindbergh’s estate. Lindbergh identified the body, then ordered its cremation without delay. Any evidence that might have identified the killer literally went up in smoke.

As the boxes in Monier’s home office overflowed with documents, he and Ahlgren strongly suspected that the killing was an inside job. How, they asked one another during their skull sessions, would an outsider know Anne was there on that particular Tuesday evening when they were almost never there except on the weekends? The house sat back a half mile from the road. How would an outsider know which window to go to? Why didn’t the dog bark? And why do it at 9:15 at night, when everyone was still moving around the house?

Their questions piled up like the paperwork. Why, they wondered, did Lindbergh keep the FBI out? When the body was found, why did he order the cremation before a full autopsy?

None of it made sense. “What we had,” says Ahlgren, “was the number-one suspect obscuring factors. What we didn’t have is a why and a how. The first thing that came to mind was abuse or neglect.” They remembered the cruel jokes and hoaxes, including the incident two months before the kidnapping when Lindbergh hid the baby in the closet. From that, they theorized that this began as a practical joke with tragic consequences. “In law enforcement,” says Monier, “we have a truism: The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior.”

In their scenario, Lindbergh arrived home from New York at his usual time and parked his car at the edge of the long driveway. Then he climbed the ladder to the nursery, maybe planning to walk in the front door with his son in his arms. Lindbergh would know which window was unlatched and that no one would be in the nursery after eight. He might also be able to approach the house without alerting the dog.

On the way down, they speculated, he accidentally dropped the boy to his death, which would account for an extensive skull fracture. He would still have had time to hide the body in the woods and pull up the drive at 8:25, honking so that everyone noted when he came home. Given Lindbergh’s public profile, no one was likely to suspect him at the outset. Once he took control of the investigation, Lindbergh decided what questions were asked and of whom. In the original outline, Monier and Ahlgren had almost nothing about Bruno Richard Hauptmann. To them he was a minor character. “People forget that others were also arrested for extortion,” says Ahlgren. ” We looked at Hauptmann as no different from the others.” Once they began to write, they realized that approach wouldn’t work. The reason was simple: To make a case against Lindbergh, they also had to exonerate Hauptmann. After all, he had the money. “So much for outlines,” says Ahlgren.

The job of analyzing the trial fell to Ahlgren . During his career he had defended people like Hauptmann, who were too poor to pay for their defense. When he went through the record, Ahlgren was appalled by what he found.

Bruno Richard Hauptmann was arrested on September 19, 1934, more than two years after a $50,000 payment was made to a man in a New York cemetery who came to be called “Cemetery John.” Earlier that month the slight German carpenter had cashed several gold certificates from the ransom with merchants in the Bronx. Although at the time of his arrest there was no further evidence linking Hauptmann to the murder, the police decided that he was the killer.

The trial was a media circus. The New York Daily Mirror hired lawyer Ed Reilly to represent Hauptmann and to provide an exclusive news pipeline. Reilly often showed up for trial with a hangover.

The defense had almost no money for expert witnesses and no access to police records, both of which would be standard practice today. Hauptmann, who spoke English with difficulty, wasn’t given a translator. Throughout the proceedings, Lindbergh sat at the prosecution table with a holstered pistol under his arm.

Much of the state’s evidence smelled unreliable to Ahlgren. At the trial, one man positively identified Hauptmann as “Cemetery John,” even though he had previously told the police that the carpenter wasn’t their man. Three New Jersey locals claimed they had seen Hauptmann near Lindbergh’s estate on or near the day of the kidnapping. One, who had just been fired from his job for stealing company funds, had been unable to identify Hauptmann in a photographic lineup and misdescribed his car prior to the trial.

Another was 87 years old and partially blind. During a post-trial interview with New Jersey governor Harold Hoffman, who was so disturbed by the verdict that he launched his own investigation, the old man identified an 18-inch-high silver cup filled with flowers as a lady’s hat.

The third testified that he had seen Hauptmann lurking about Hopewell on two separate occasions and that he had reported this to the police. The opposite was the case: Before the trial, he had told the police he hadn’t seen anyone suspicious prior to the child’s disappearance. Later he admitted to Hoffmann that his testimony was due in part to a desire to share in the reward money.

None of this information was available to the defense.

In retrospect, Ahlgren identified nine factors of evidence that ultimately sent Hauptmann to the electric chair. The most important may have been the money.

“Hauptmann may have been an extortionist,” says Ahlgren, “but the issue is: Was he the guy on the ladder in New Jersey? If the defense had admitted his involvement in the extortion attempt, they would have eliminated most of the testimony against him. He may have gone to jail for a short period of time, but he wouldn’t have gotten the electric chair. Instead they had all these witnesses who made Hauptmann look like a liar about the money. And if he’d lie about the money, well, why wouldn’t he lie about the murder?”

A few days before Christmas 1935, with Hoffman’s investigation underway and Hauptmann’s execution imminent, Lindbergh moved his family to Europe, where he remained for the next several years. Bruno Richard Hauptmann was executed on April 3, 1936.

Even if Hauptmann was innocent, was Lindbergh cold enough to let another man die in the electric chair? The authors think he was. “They didn’t call him the Lone Eagle for nothing,” Monier says.

What they needed was an eyewitness who could place Lindbergh in Hopewell early in the evening on March 1, 1932. They began to hunt for Ben Lupica.

In 1932 Lupica was a Princeton Academy high school student living near Hopewell. A few hours before the kidnapping, he was passed by a man on the road with a ladder in his car.

The prosecution never called him as a witness. Ahlgren was troubled. “Here was the only guy to have seen someone driving around Hopewell with a ladder, and they didn’t call him ,” Ahlgren says.

But where to find him? No Ben Lupicas were listed in the phone book, and Princeton Academy no longer existed.

Ahlgren wondered if Princeton Academy could have been a prep school for Princeton University? He worked out the dates when Lupica might have graduated and then placed a call to Princeton University’s alumni association.

It was a long shot that paid off. Ben Lupica was now a retired chemist still alive in upstate New York. Despite the dozens of books and articles written about the case, no one had interviewed him since the trial. Through his wife, he agreed to meet with them.

Sixty years after the event, Lupica’s memory was sharp. He was retrieving the mail when an oncoming car with New Jersey plates pulled over to its left on the narrow dirt road to pass him. The lone driver was wearing a fedora.

Lupica hadn’t paid attention to the driver: “He was a white guy,” he told Monier and Ahlgren. “He could have been anyone, anyone in the whole world.”

Ahlgren understood then why the prosecution hadn’t called Lupica. Hauptmann’s car had New York plates.

Something else Lupica said made both of their pulses race: He wasn’t sure, but Lupica thought the car was a Dodge because it had a distinctive grille and no hood ornament. The other car with a distinctive grille and no hood ornament was a Franklin, the same car Lindbergh drove.

When their book Crime of the Century: The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax was published last spring by Branden Books, a small Boston publisher, Ahlgren and Monier were suddenly thrust into the public eye. They did more than 100 radio interviews and took a trip to New York, where Arthur Miller interviewed them for “Court TV.” An Associated Press story was published around the country.

Not all the reactions were positive. Reeve Lindbergh, a 47-year-old writer living in northern Vermont, thought the book was a cruel attack on her parents. “Yes, my father had a fine sense of humor,” she told The Boston Globe. “But to suggest he was capable of murder is unthinkable.”

Geoffrey C. Ward, who scripted a PBS “American Experience” segment on Lindbergh, agreed. “It seems to me obscene to blame the father of a murdered child for the murder without any evidence at all,” says Ward, who concluded Hauptmann was guilty as charged.

Yet Ahlgren and Monier aren’t alone. In January, Atlantic Monthly Press published Lindbergh: The Crime, an account of the case by Noel Behn, the best-selling author of Kremlin Letter and The Brink’s Job. According to Behn, who says he obtained access to Governor Hoffmann’s papers during the eight years he spent researching his book, the child was killed by one of Anne Lindbergh’s close family relatives. “A cover-up,” he says, “was orchestrated by Lindbergh.”

In the meantime, Ahlgren and Monier have received letters and calls from the descendants of domestic help and bluecollar workers from around Hopewell. Most, like the daughter of an airplane mechanic, claim that their parents had told them over the years that Lindbergh was somehow involved in the death of his son. “Every time the subject of Hauptmann came up,” the woman wrote, “my dad would say, ‘They killed an innocent man. Lindbergh did it.’ “

They know the case may never be resolved. “When I lay awake at night,” says Monier, ”I’d like a better resolution. There are just too many unanswered questions.”

Ahlgren believes they could get an indictment against Lindbergh based on their research. “But I don ‘t know if we could get a conviction,” he says.

Monier agrees: “You’d be taking on a giant.”

Still, both have come to look at their own roles in the criminal justice system in a new light. “For me,” says Ahlgren, “it has to do with Hauptmann’s prosecution. I realize the legal protections we have today aren’t that old, and they’re not necessarily here forever.”

“The other side,” says Monier, “is that police officers have a tough job to do, and we have to do it carefully if we don’t want guilty people to go free.” Beyond that, he adds, “I think my perceptions of how we look at historical figures has changed. I realized that the last chapter on a public figure is never fully complete.”