Continuum | The Farmer’s Life: Dispatches from Chickadee Farm in Craftsbury, Vermont

Honoring women homesteaders and farmers and their way of life.

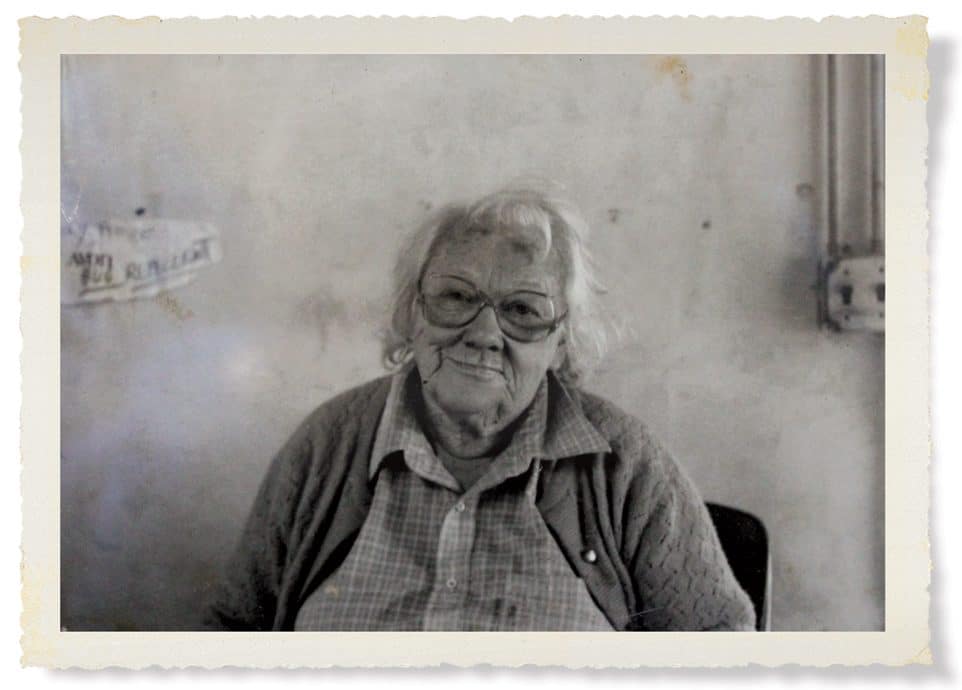

Years after taking this photo, the author never stopped wondering about who this woman was.

Photo Credit : Julia ShipleyA girl from the suburbs, I longed to become a rural woman. Not that I had specific words for this urge — or even role models. My relatives were enamored with fashion and theater, restaurants and sports events, books and museums. But a close friend of the family was a professional photographer; hence I learned to handle a camera early on. Through its viewfinder, I documented my affinities: old stone walls, steers in a field.

One day, in my 12th summer, I begged my father to drive us to the Duncan’s farm stand, not far from where we lived in Devon, Pennsylvania. It was a place that sold sweet corn and watermelons throughout summer, and pumpkins in the fall — all grown on a ribbon of land beneath the transmission lines. When I asked the lady behind the counter if I could take her picture, she replied, “Oh, I don’t know what for.” Her voice was tiny and high, like a child’s, although she was so much older than me.

Photo Credit : Julia Shipley

I took her picture that day, and I’ve kept it with me ever since, packing and unpacking it as I moved from home to home into adulthood. Where I live today is hundreds of miles from her farm stand, yet her picture hangs above my desk, supervising me with that sly tired smile. What does she know? I wonder, now that I am midway between the age of the girl photographer and the old lady she photographed.

Until recently, I knew nothing about this woman personally, nothing at all. But I’d study the sad mirth in her eyes, gazing straight at me — the me of all the ages, regardless of years. Despite the fact that that moment was over, I was still listening.

I wanted to know her name, at least.

I took the photograph off the wall last fall and drove with it back to the farm, where I found an older man relaxing in a chair beside the woodpile. “Could you tell me who this is?” I asked.

“Well, I don’t know, let’s see,” he said, taking the photograph with both hands onto his lap. Then he said tenderly, “Oh. That’s Mom.”

And then he told me about her:

She grew up on a farm, rode a horse to school and smacked its hind to send it home while she was in class all day. In high school, she was the class secretary. My father was the class president.

One spring when Dad broke his leg, she pulled me from school every other day to plant sweet corn.

She always had all kinds of ideas — she was an idea lady, kept notebooks full of ideas. She wanted me to build her a doghouse that was also a cold frame. Everything had to have all kinds of purposes.

She never drank, except she ate raisins soaked in vodka for arthritis. We’d tease her, “How many raisins have you had today?” Never smoked, either. But she was diagnosed with lung cancer on Valentine’s Day; she died on Mother’s Day.

That was 12 years after I took her picture, when she was 80.

The Duncan’s farm stand looks about the same as it did when my dad brought me over with my camera almost 30 years ago. This time, the sweet corn cart is stuffed with potted chrysanthemums; the woman’s son, Stephen, buys them wholesale. Nearby are tables of pumpkins. I pick one and try to pay for it where she used to sit, but Stephen won’t let me. I take a picture of him holding the photo of his mother that I took of her sitting where he is sitting now. As I snap the image, the years and faces ricochet, then, now, what becomes of us, stirring up … oh, I don’t know, what’s the word for admiration and a little sadness?

What I carry away is more substantial than the pumpkin filling my arms, hard against my chest and as lovely as the hues of all those mums: her name. “This lady in the picture, your mom, what’s her name?” I ask Stephen before I leave.

“Evelyn. That’s Evelyn.”

Julia Shipley is the author of three poetry chapbooks and most recently a prose collection, Adam’s Mark: Writing from the Ox House, supported by a 2010-2011 Vermont Arts Council Creation Grant and published by Plowboy Press.

Julia Shipley

Contributing editor Julia Shipley’s stories celebrate New Englanders’ enduring connection to place. Her long-form lyric essay, “Adam’s Mark,” was selected as one of the Boston Globes Best New England Books of 2014.

More by Julia Shipley