On Islandness | First Person

The memory of living surrounded by ocean can last a lifetime. Learn how time spent on an island can change you forever in this essay by Brian Doyle.

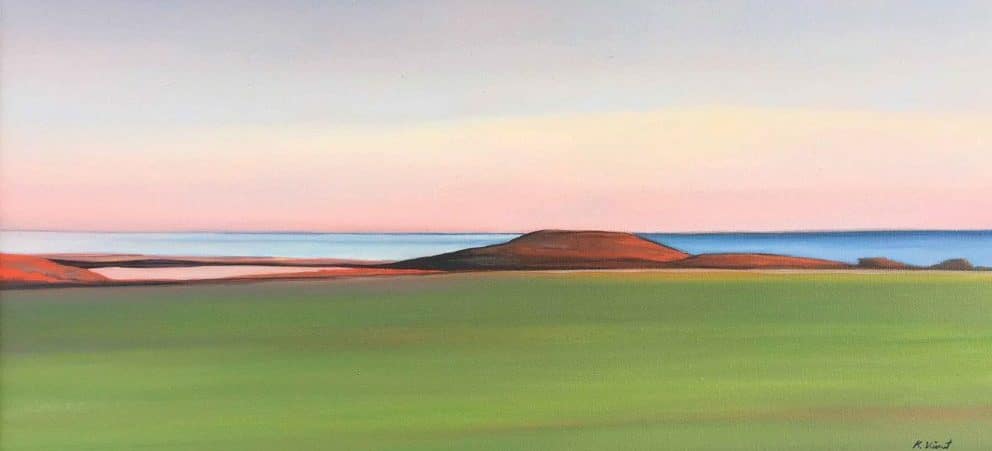

Slowly Setting, by Kenneth Vincent

Seals bobbing up like cheerful bald uncles in the river near the lighthouse, and night herons groaning out of the trees on their way to work at dusk, off to their nightly winnowing of the frog population; bluefish pursuing prey into the shallows along the beach with such violent fury that you could almost hear them snarling and gnashing and cursing and slashing; deer sleeping in tiny hollows beneath black pine and black oak; friends of various shapes and sorts and styles, from dear to casual; our one policeman, who knew everyone on the island all too well, all too well, as he said; snow drifting across the road in tendrils and dervishes; blackflies and greenheads descending in their zillions, ravenous for blood and snickering at the latest product guaranteed to fend them off, as if anything but torch and armor would suffice to battle a blackfly intent on poking a dozing essayist.

Only once, for a year, did I live on an island, and all these years later I begin to think that we should all live on an island, at least once, at least a little while, just to have done so, to have been detached from the pompous main, the arrogant majority. To live on an island is somehow to acknowledge and salute the small, the isolate, the humble; on an island there is no question that you are at the whim and mercy of the sea, with which there is no serious argument, it being far more powerful and patient than the most obdurate rock. An island is itself a temporary battlement, thrust into the air only for a moment in the much longer story of the ocean, from which came all things, and to which all things return; but to perch on that narrow turret for a while is to be powerfully reminded that empires and nations and countries and cities finally are small, and the ocean is immense, a profligate language of which we know only a few words, a story we are just beginning to read, as awed and amazed as children.

Islands are owned by the sea and loaned to people; islands are us, small and brave and temporary. It says something piercing of human beings that island residents love their stony ships, and are proud of their independence from the larger land, and they depart their islands with reluctance; much as we love the fragile vessels into which we are born, and think ourselves utterly different from all other such beings, and mourn the time when we too depart the earth, to sail into the stars, as what we were washes eventually back into the sea.

Two or three times in the first years since I walked off that jetty that morning I went back to that island, and spent a day strolling the beach, and sipped ale in the pub, and drove along the only road, watching for a flash of foxes; but some part of me knew that I did not live there any more, that I was a guest, and no longer a resident; and I stopped going. But this morning, thinking of that long lean quiet unassuming friend, I feel not sadness, that I left, but joy, that the island is resident in me. I hope and pray that it will always be so.