Myrtle the Turtle at the New England Aquarium | Queen of the Deep

Generations of New Englanders know Myrtle the Turtle as an aquarium celebrity. For some, she’s also a timeless comfort in a fast-changing world.

Weighing a quarter ton and coming up on her estimated centennial in the next 10 years, Myrtle may share the New England Aquarium’s Giant Ocean Tank with 1,000 other creatures but is truly in a class of her own.

Photo Credit : Brian SkerryBy Joe Keohane

It’s nasty out on Central Wharf: rain, sleet, snow, high winds. It’s one of those April days when Boston makes a last-ditch attempt to finally and irreparably break the spirit of its inhabitants, which it generally does after coaxing them into relaxing their guard with a string of impossibly beautiful spring days.

I walk into the New England Aquarium an hour before it opens. It’s quiet. I walk through lobby doors I have been walking through since I was a kid, and I walk by penguins I have been walking by since I was a kid, too. Though probably not the same penguins. When the facility opens to the public at 10 a.m., at limited capacity due to Covid-19, it will still be pretty quiet. During the worst of the pandemic, the aquarium was closed. The penguins got used to it. In fact, when the staff was preparing to reopen, they had to reacquaint the penguins with human sounds. They did this by piping in crowd noise at a low volume, and then raising it in increments until the birds were again ready to receive the general population.

The penguins weren’t the only animals that had to adapt, though. At the start of the pandemic, staffers who work with the harbor seals had to acclimate them to the sudden appearance of masks. They did this by taking their masks off and putting them on during feedings, forging in the seals’ minds a connection between the masked person and the caretaker they knew and trusted.

But I’m not here for the penguins or the seals. Led by an aquarium staffer, I walk around the Giant Ocean Tank, on our way to the top. It’s 23 feet tall and 40 feet wide, containing about a thousand Caribbean reef animals and 200,000 gallons of warm water. It glows blue in the darkness of the aquarium, and it still feels vaguely scary, and thrilling, and precarious to be around, as it did when I was a kid.

We climb the last set of stairs leading to the top of the tank, step out, and there she is, as she’s always been, ancient and ageless, the 500-pound dinosaur queen of her domain: Myrtle.

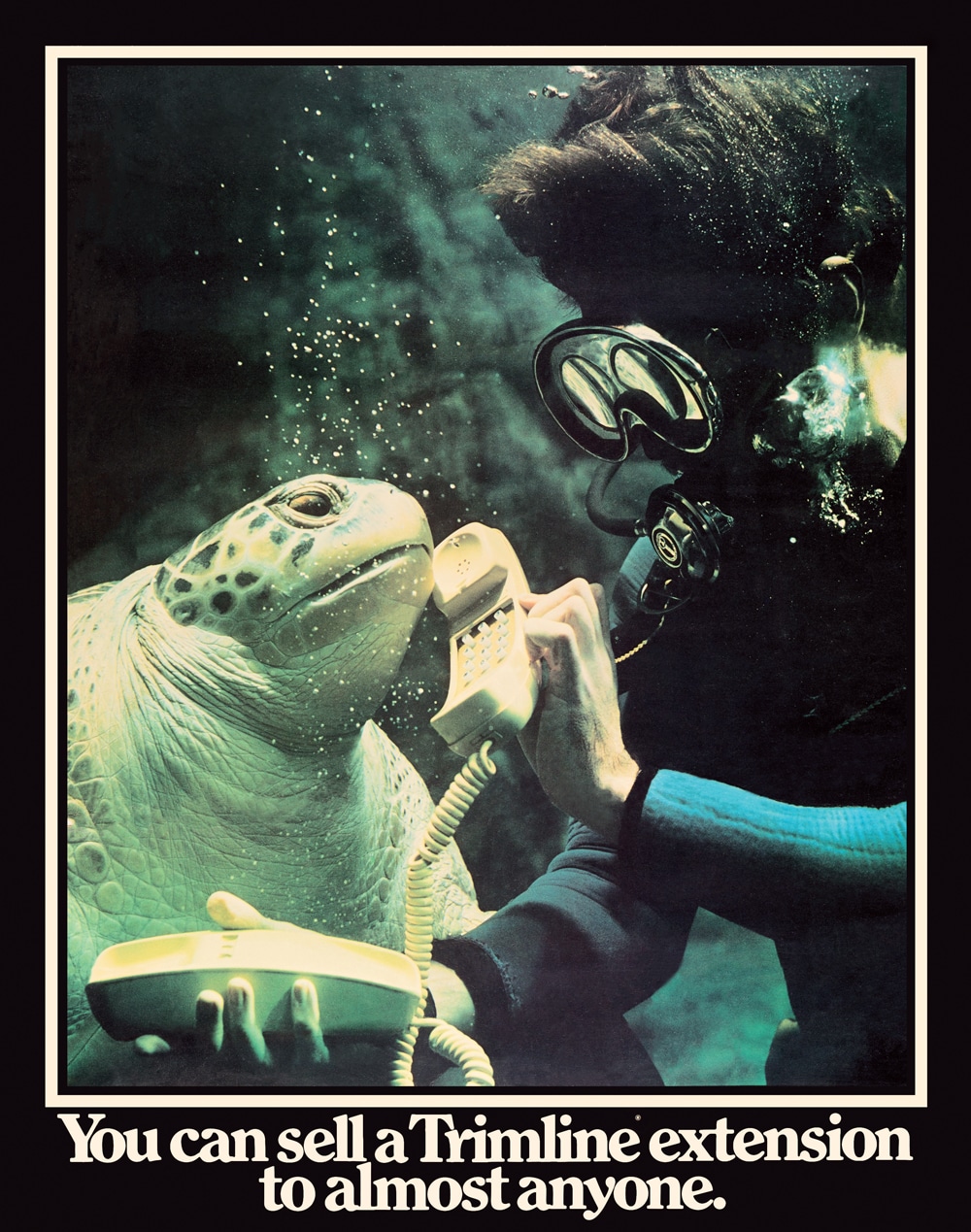

No one really knows where Myrtle the Turtle came from. They know that she came to Boston from a now-defunct aquarium in Provincetown in 1969, and again in 1970, in what was intended to be a temporary exchange. But then the Provincetown facility shut down, and Myrtle became a permanent resident of what was then still a brand-new New England Aquarium. The face of the institution and star of the tank for more than 50 years, she has been visited by millions of people, a few of whom even swam with her. These include Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler and Joe Perry, country star Rex Trailer, three famous clowns (Bozo, Willie Whistle, and Ronald McDonald), and a mime named Trent Arterberry.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of New England Aquarium

When Myrtle arrived here, she weighed 225 pounds. Weight isn’t the best way to gauge a turtle’s age—the size of reptiles can vary wildly depending on where and how they live—but records at the donor aquarium were scant, so it was all that aquarium scientists could go on. At the time, they estimated she was between 20 and 40 years old, which means today she is between 70 and 90 years old, making her the oldest known green sea turtle in captivity. “More realistically, we think she’s in her 90s—somewhere around that range,” says Mike O’Neill, the supervisor of the Giant Ocean Tank. “Hopefully she’ll live decades more.”

O’Neill grew up coming to the aquarium. A native of Hingham, on the South Shore of Massachusetts, he has fond memories of looking at Myrtle from the top of the tank as a kid. Now, in his capacity overseeing the delicate reef ecosystem of the tank, he’s the person most intimately acquainted with her.

“She’s a stellar community member in the Giant Ocean Tank,” he says. That said, she’s also the largest animal in the tank. And as such, she’s unafraid to assert herself, O’Neill says. If another creature is in her space or in a preferred sleeping spot, she’s not above throwing her weight around. Likewise for newcomers: When the aquarium staff introduce new animals to the tank, they’ll first put them in enclosures and drop them into the tank to acclimate them to their new home. If one of these enclosures ends up in a place that displeases Myrtle, she’ll move it. Otherwise, though, “we don’t really have to worry about any negative behaviors, or aggression, or anything like that,” O’Neill says. “She’s just a big gentle giant, basically.”

Certainly, she has little reason for existential concern. The Giant Ocean Tank is a low-stress environment for a green turtle. This sets Myrtle apart from her peers in the open ocean. “If you’re an adult sea turtle in the wild,” O’Neill says, “your concerns, in terms of ending your life prematurely, are going to be predation from large sharks and other big intimidating creatures, boat strikes, fishing gear entanglement, and things like that.”

Though green sea turtles, aka Chelonia mydas, still appear around the world, they are an endangered species, due to the aforementioned factors, as well as a few more, including oceanfront development, climate change, and illegal trade (not for nothing have they been nicknamed “the soup turtle”). The beaches where sea turtles lay their eggs—more than 100 at a time, generally—are eroding and getting warmer. The waters in which they swim can be polluted, and the sea grasses and reefs they rely on for food are being degraded. The situation is not improving, either: According to a 2013 report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, “As recently as the 18th and 19th centuries marine turtles were very abundant, with some populations numbering well into the millions. But in the last several hundred years, we have overwhelmed the species’ ability to maintain their numbers.” All this makes Myrtle more significant, and more valuable to researchers, but it also doesn’t touch her personally. “She doesn’t have to worry about any of those things here,” says O’Neill.

Green turtles are great wanderers and brilliant navigators, with females returning faithfully to the same nesting grounds in which they were born to lay eggs every few years. They can migrate thousands of miles between foraging—which they do in the coastal waters of some 140 countries—and nesting, which they do on beaches in 80 countries. Some may traverse an entire ocean basin in their lifetimes. Myrtle does not have that kind of latitude, obviously, but she can move pretty freely in the tank, O’Neill says. Greens are the second largest of the seven species of sea turtle, behind the leatherback, but despite their bulk, they are agile swimmers. They can maneuver almost like drones, thanks to their four flippers. Green turtles are solitary by nature, but exploring the heavily populated reef, and watching and occasionally descending upon the divers charged with its maintenance, helps keep Myrtle stimulated, and by extension keeps visitors to the aquarium stimulated.

“I don’t know of many sea turtles that have had the legacy that Myrtle has had,” O’Neill says. “In the 50 years she’s been here, when you do the back-of-the-envelope calculations, that’s like 60 million people who have seen her. The whole point of having the aquarium is to promote ocean creatures and ocean life, and get people to care about the ocean. And that Myrtle has been able to have that big an impact, as just one turtle, is pretty awesome.”

And she will, he believes, continue. “In general, she’s doing great,” says O’Neill. “I’m hoping to have a full career here and retire, and still Myrtle will be in the giant fish tank. That’s my goal.” O’Neill is 31 years old.

Myrtle’s morning begins when day breaks over the tank. She generally sleeps through the night, usually at the top of the reef near the surface, her rhythms regulated by artificial lighting designed to replicate the changing light of the passing day. At 8 a.m., relative darkness yields to blue LED light, which simulates dawn. This stirs her. Then the blue light yields to white light, which wakes her up completely. By 9 a.m. she’s swimming, her serrated beak fixed in an expression of grim disapproval, her vast bulk hovering around the feeding platform. There, at 10 a.m., she will be fed by a volunteer named Alan Marshall.

Alan is a retirement plan administrator at a local advertising firm. He’s also a certified diver and a longtime member of the aquarium. About three years ago, when his company cut his hours, he volunteered here. He loves it, he says. He is a classic old-school Boston guy, equal parts gregarious, boyish, wised-up, witty, and sarcastic. He doesn’t really drop his r’s—few do at this point—but everything he says comes out with a little top spin on it, in a way that marks him as a local. He works here one day a week, helping to feed Myrtle and donning the dive suit to clean the tank. “We vacuum, and scrub, and do the windows,” he says. “My wife wishes I’d like to vacuum and dust at home as much as I do here. I think she’s buying me a whole setup for home, so I can put all the equipment on and then vacuum. But I said, ‘It doesn’t really ring the same.’”

Photo Credit : Courtesy of New England Aquarium

At 10 a.m., when the aquarium officially opens, Alan walks out of a staff area behind the top of the tank with a plastic bin containing a few pounds of greens and seafood. “Today,” he announces, “we got some capelin—or as we like to say in the kitchen, capelini—some squid tacos, which is basically squid stuffed with capelin and some vitamins. And then some lettuce, and Brussels sprouts, and cabbage. Brussels sprouts are usually big, she’s a big fan, but lately she’s been shunning those Brussels sprouts. So we look silly when we say that it’s her favorite.”

Alan opens the gate at the edge of the tank and steps out onto the feeding platform, and Myrtle surfaces obligingly. The aquarium sources most of her food from a local restaurant supply company, and Myrtle’s caretakers try to switch it up. Green turtles are omnivores and foragers. They like variety. “We tried green peppers,” Alan says. “Not a big fan. We tried kale. Not a big fan. I mean, who is? We tried some other green things. We tried beets—not that those are green, but somebody thought that would be fun to see how she reacted to the beets. Maybe get her poop to turn red. I don’t know. She didn’t eat the beets. Nobody ate the beets.”

Feeding time in the Giant Ocean Tank is carefully coordinated. Green turtles are typically very curious creatures. If there is any other human activity in the tank—if divers are down cleaning the substrate, say, or feeding the other inhabitants—Myrtle will go check it out, an experience one staffer likens to having a spaceship come down on your head. Oftentimes, though, she just wants her shell scratched. The top layer of her shell, where the big scales or “scoots” are, is akin to human fingernails. There is sensation there, and, as she readily reminds people, it frequently requires attention.

I lean over to take a photo of Myrtle. “Don’t drop that,” Alan says. “Though you look like you know not to drop that.”

“Do a lot of people drop phones in the tank?” I ask.

“There have been a lot of things dropped in the tank,” Alan says. “I would say phones are probably the least dropped. Glasses are a good one here. Somehow hotel room keys—I don’t know how your room key comes out, but maybe it’s attached to the phone. Hair pins. Lens covers for good cameras. We try to get them right away.”

At various points in the feeding, Alan offers me his assessment of his position at the aquarium.

“It’s awesome,” he says.

“It’s so awesome,” he says later.

“It’s super awesome,” he concludes.

All the while, Myrtle bobs and wheels and eats a few feet from me. And as I watch her, I’m strangely moved.

What is it about this animal? I mention to Mike O’Neill how poignant it is to come here as a 43-year-old man and visit an animal I have seen since I was a kid, and find her looking pretty much the same as she did 35 years ago. “There’s something special about turtles,” he says. “Humans really like turtles. And Myrtle is one of the best examples of a charismatic creature that is extremely memorable. Folks may not keep in mind all the species of fish, or what’s in one exhibit versus another, but almost everybody who has come here has that imprint from Myrtle.”

“But why do you think it is?” I ask. “What does she evoke, exactly?”

“Oh man,” he says, sitting back. “I mean, then I feel like we have to get into human behavior and cognition. I don’t know. Maybe it’s that they have the longevity that they have, or they have the size that they have. But yeah, for some reason, turtles have been a fixture for humanity for a long time.”

Photo Credit : Webb Chappell/New England Aquarium

Among indigenous societies going back thousands of years, some saw a special kinship between turtles and humans. Native cultures ranging from Asia to the Americas believed that the world is carried on the back of a turtle. That earthquakes happened when the turtle moved. That the world may someday return to the sea. Native Americans were among them; some called North America “Turtle Island.”

It wasn’t until European explorers arrived, though, that demand for the animals exploded. It has been said that green turtles made the peopling of the so-called New World possible. Which means, ironically, that our society was built on a turtle’s back, in a sense. Because green turtles had the misfortune of being the most delicious of the sea turtles, favored both for their meat and their calipee—the cartilaginous material on the inside of the shell—they quickly became a sought-after foodstuff for European explorers, traders, and pirates in the 17th century. Finding them was a godsend. They provided an abundance of good protein, and, stored on their backs in ships’ holds, they could go weeks or months without food or water, providing a welcome break from the seaman’s usual grim diet of hardtack and salt beef. Turtle meat, oil, and sometimes eggs were also seized upon as antidotes to both scurvy and erectile dysfunction, treatments for syphilis and general listlessness, and, in one instance, a means of caulking a hole in a stranded ship. Not for nothing did Christopher Columbus call turtles “the most valuable reptile in the world.”

By the 19th century, green turtle meat had broken free of the lowly ship’s hold and risen to become a symbol of Victorian affluence among Americans and the English. It spread to the white aristocracy in the West Indies. It was believed to line the stomach, increasing the body’s capacity to ingest even more rich food. According to one account from the period, turtle soup “has become a favorite food of those who are desirous of eating a great deal without surfeiting … by the importation of it alive among us, gluttony is freed from one of its greatest restraints.” Europeans took an animal that was sacred to the people they were conquering, and turned it into a means of helping themselves achieve ever higher levels of self-gratification (there’s a metaphor for you). The demand for green turtle meat nearly wiped out the species. The population never recovered.

Yet sea turtles were a fixture long before humanity came onto the scene, in fact. As far as we know, they have been around for more than 100 million years. They are basically dinosaurs, only unlike dinosaurs they made it to the 21st century. In 1979, the naturalist Jack Rudloe remarked upon this: “It’s hard to say what the turtle’s key to success is. Even though his movements are generally slow, his hearing is poor, and he has little in the way of brains, the turtle can be called one of the most successful animal stories in the world.”

So to see Myrtle up close is not only to connect with the history of Western civilization; it’s also to connect to the deep history of the planet, to a world that existed long before the genus Homo blundered into existence a few million years ago. To look at Myrtle is to look at time itself. There’s a stillness, a quiet awe that comes over you when you see a representative of a species that has lasted 50 times longer than your own.

In his journal in 1856, Henry David Thoreau, that august New Englander, wrote about this, too:

The young turtle spends its infancy within its shell. It gets experience and learns the way of the world through that wall. While it rests warily on the edge of its hole, rash schemes are undertaken by men and fail. French empires rise or fall, but the turtle is developed only so fast. What’s a summer? Time for a turtle’s egg to hatch. So is the turtle developed, fitted to endure, for he outlives twenty French dynasties. One turtle knows several Napoleons. They have no worries, have no cares, yet has not the great world existed for them as much as for you?

Portraying turtles as being blithely unworried by the world may be a case of Thoreau being Thoreau, though. Certainly an animal that lays as many eggs as a green turtle can’t fairly be called oblivious to the hazards of life in the world. Of all the eggs that green turtles lay, very few actually make it, with the vast majority falling prey to ghost crabs, bluefish, gulls, and the like. And yet they endured. Over millions of years, the species ran the numbers, adapted, and survived. Seeing the result of that—one of the very few that hatched out of an egg buried on a beach, boiled out of that sand with 100 would-be siblings, scrambled to the sea, entered the sea, and survived in the sea for 20 to 40 years, defying crushing odds set by man and nature alike—is like meeting a survivor of the Somme. Seeing such a creature gliding unhurriedly through a warm tank, inches from you, knowing what you know and what she’s done, is awesome.

Photo Credit : Vanessa Kahn/New England Aquarium

Is that why Myrtle makes us feel the way we do? Awe, as psychologists are only beginning to discover, confers some unusual benefits. Studies have shown that awe makes us feel more humble, more connected to others, and more generous. It expands our perception of time, and improves our mood and well-being. How does it do this? Paradoxically by making us feel insignificant. Researchers have found that when people experience awe, they experience something called “the small self.” Experiencing awe makes us feel small relative to our surroundings. In doing so, it makes our personal concerns feel smaller, and that makes us feel better.

When people talk about awe, they usually talk about things like mountains, or transcendent religious or spiritual experiences. But could it apply to a turtle? I asked UC Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner, one of the first in his field to study awe, what he thought. “Awe arises with encounters of vastness we don’t understand,” he replied. “Giant sea turtles are amazing—and I find them awe-inspiring—because they are vast in many ways: their size, their age, and how they move extraordinarily slowly.” He concluded: “A great source of awe.”

I put the same question to Summer Allen, a neuroscientist and turtle enthusiast who has also studied awe. “I wonder if the fact that Myrtle is both so big and so old might play a role in eliciting awe,” she replied. “I also wonder if there’s something about the fact that sea turtles are so different from us that could play a role. They are prehistoric creatures that spend almost their entire lives alone. They don’t parent their offspring or form social bonds. They travel thousands of miles and somehow make their way back to the nesting beach where they were born. They live amongst whales and sharks and probably creatures no humans have seen before. Their existence is so utterly different from ours.”

As alien as her kind may seem, however, Myrtle is familiar. She is the stranger we know. She is part of our personal history, at least those of us who have been seeing her for years. And maybe this is the final clue to why we feel the way we do about her. Staffers I talked to at the aquarium spoke often of the power of multiple generations experiencing Myrtle. A man, such as myself, can take his daughter, as I have, to see an animal that he saw when he was her age. And the animal will be where she’s always been, and she will be about the same.

Photo Credit : Keith Ellenbogen

And that, too, is awesome. Through 50 years here, as everything changed around her, Myrtle has stayed constant. Almost every tall building in the city was erected during her tenure here, including the Hancock Tower and the aquarium’s next-door neighbor, the Harbor Towers. The nearby Central Artery was razed and replaced by the Big Dig and the Green-way. The Bulger brothers happened. Busing happened. Gay marriage. The Internet. Gentrification. The Gardner Museum heist. The marathon bombing. Kevin White, Ray Flynn, Tom Menino, Marty Walsh, and Boston’s first female mayor and Black mayor, Kim Janey—they all happened. The 1986 and 2004 Red Sox happened. Tom Brady’s six Super Bowl wins happened. The Celtics won seven championships, and the Bruins two. The old Boston Garden was torn down. Bill Weld jumped into the Charles River, and then as if by magic all of Boston’s dirty water was made clean.

All the while, as the city underwent vast physical, and social, and demographic, and economic upheaval, Myrtle quietly wheeled, and glided, and napped, and ate. She is a fixed point in the recent history of a dynamic place, and there is something reassuring about watching a creature that has been unchanged and untouched during a period of such relentless turbulence. She is a fixed point in the life of a city that for all its historical import has changed beyond recognition.

Rarer still, though, Myrtle is a fixed point in the equally tumultuous lives of the millions who have come to see her. And it was this that was on my mind as I watched her wheeling and gliding on that nasty day in April 2021. We were struggling to emerge from the pandemic, and grappling with multiple other crises besides. The year had taken a toll, and had found me feeling intensely nostalgic, which is by no means my default mode. This isn’t uncommon: Psychologists have found that people frequently experience nostalgia in times of intense stress or hardship, or when they feel their lives have become somehow severed from their pasts in a way that keeps the two halves from fitting together as they once did. This sensation might occur because one’s life has changed drastically, or because the world has changed drastically, or both.

Certainly that was 2020 for most of us. Nostalgia can remind us of people we love, or memories we cherish, or episodes when we overcame something and became stronger, all of which can help us cope with present difficulties. By reflecting on the past and applying it to the present, we can create a feeling of continuity, and mend the break between our old lives and our new lives and perhaps feel less adrift in the currents of time and history, and more whole.

Is it in a turtle’s power to do that? Maybe. And maybe that’s why we come to see her. Maybe that’s the key to her power: tranquility in chaos. Grace and persistence against terrible odds. Continuity. Times may be hard, the future uncertain, the comforts of the past slipping away, but maybe there are worse places to be than on the back of a turtle.

When not communing with ancient sea turtles, Joe Keohane’s been spending a lot of time looking at how we humans connect with each other. Join in our first “Conversations with Yankee” webinar on December 9 to hear him talk about his new book, The Power of Strangers: The Benefits of Connecting in a Suspicious World. To register, go to newengland.com/conversationsyankee.