History

Mailboat on Great Pond, Maine | The Summer Mailboat

Every June 1 since 1950, Dave Webster and his boat have confirmed the start of another season for residents of Great Pond, Maine. Excerpt from “The Summer Mailboat,” Yankee Magazine June 1988 In 1943, the summer Dave Webster turned 15, he began delivering mail by boat on Great Pond, an 8,000-acre lake about 15 miles […]

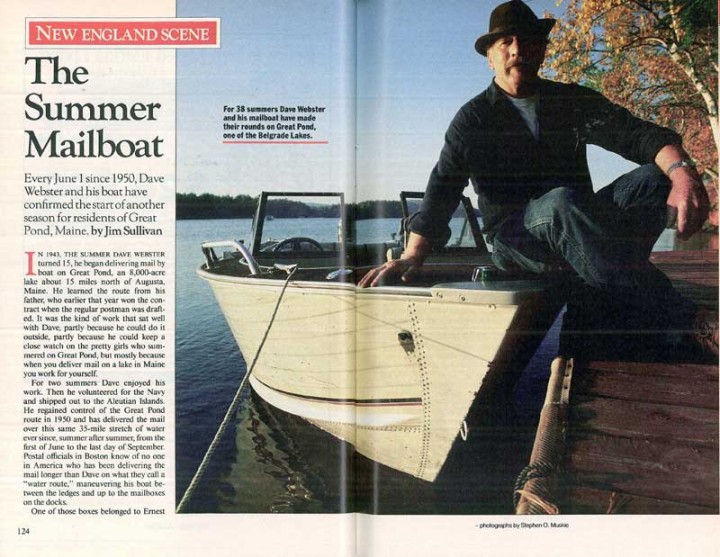

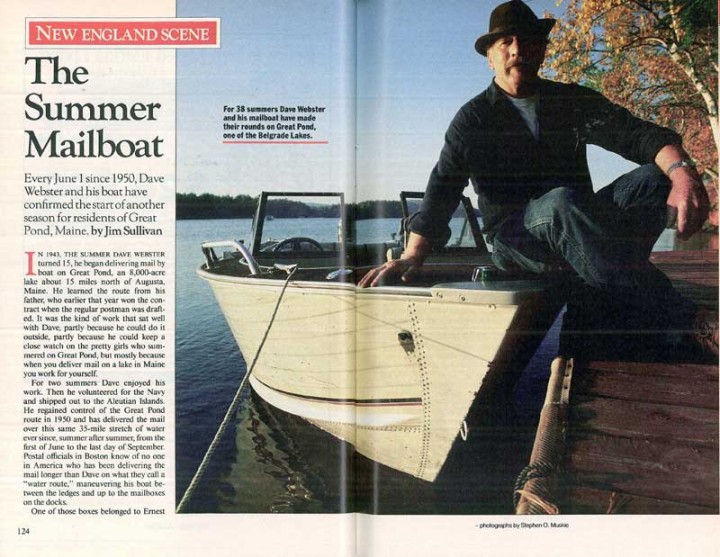

Every June 1 since 1950, Dave Webster and his boat have confirmed the start of another season for residents of Great Pond, Maine.

Excerpt from “The Summer Mailboat,” Yankee Magazine June 1988

In 1943, the summer Dave Webster turned 15, he began delivering mail by boat on Great Pond, an 8,000-acre lake about 15 miles north of Augusta, Maine. He learned the route from his father, who earlier that year won the contract when the regular postman was drafted. It was the kind of work that sat well with Dave, partly because he could do it outside, partly because he could keep a close watch on the pretty girls who summered on Great Pond, but mostly because when you deliver mail on a lake in Maine you work for yourself.

For two summers Dave enjoyed his work. Then he volunteered for the Navy and shipped out to the Aleutian Islands. He regained control of the Great Pond route in 1950 and has delivered the mail over this same 35-mile stretch of water ever since, summer after summer, from the first of June to the last day of September. Postal officials in Boston know of no one in America who has been delivering the mail longer than Dave on what they call a “water route,” maneuvering his boat between the ledges and up to the mailboxes on the docks.

One of those boxes belonged to Ernest Thompson, the playwright who wrote On Golden Pond. He used Dave as a model for a character named Charlie, a mailman who went around saying “Holy Mackinoly.”

“I never said ‘Holy Mackinoly’ in my entire life,” Dave told me right away when I joined him last spring for the first run of the season.

A warm breeze out of the west rocked the boats tied to the dock, their bows squeaking against the old timbers. There was a faint chop on the water. Dressed in a white T-shirt and new dungarees cut off at the kneecaps, Dave walked ahead, carrying a batch of mail in a white canvas bin.

“We’ve got a hundred boxes out there now,” he said. “That’s four times as many as we used to have when my father first took the route on and probably twice as many as L.L. Bean’s brother Irving used to have when he delivered mail before us.”

He tucked the mail in the open bow of a 16-foot powerboat, then put his hands on his hips and stared out over the lake. He studied it, like a carpenter checking the grain in a piece of lumber. I said something about how he must know this lake better than anyone.

“I’m commencin’ to learn it,” he said. “Commencin’ to learn it.” With a turn of the key he started the engine, shifted into reverse, and we backed away from the dock.

Only a handful of these water routes survive in the Northeast. “I don’t make any money on it,” Dave told me with resignation. “But I’ve grown attached to it.” Five years ago he sat down with an accountant, and when they figured out all the extra costs of the mail route, it was clear Dave was losing money. Reluctantly he asked the Postal Service for a raise.

“If you got a job, you hang onto it,” he said. “I was trying to get an increase without them taking the route away. It wasn’t like I wanted top dollar. I just wanted to break even.”

The Postal Service gave him half of what he asked for, $6,200 a year, which figures out to about $4.50 an hour. “That’s if everything goes smoothly,” Dave pointed out. “If the mail boat breaks down somewhere on the lake, then two boats have got to be called out. One boat tows the broken-down boat in, and the other boat continues on with the mail. Somehow you’ve got to fulfill your obligations. I mean, people are depending on you.”

They were depending on Dave this morning. Women peeked from behind lace curtains in camp windows, checking and rechecking the lake while men puttered around in the yard, nailing a spare shingle on the woodshed or cutting wild grass away from the garden. Dave throttled back to an idle as he inched his way up to each dock. There he stood and balanced himself in the center of the boat, one hand gripping the steering wheel to steady the boat while the other reached for the mail. Everyone hustled down to the boat to scoop the mail out of Dave’s hand.

He smiled and answered their questions about who had returned for another season. To the summer residents of Great Pond, Dave is more than a mailman. He is the link connecting them and one of the elements that makes a community of a hundred separate cottages rimming the shore of a giant lake. A tax lawyer from Camden, New Jersey, still dressed in wingtip shoes, remarked, “If it wasn’t for Dave Webster, this wouldn’t be Great Pond.”

Back out on the water, Dave stood at the steering console, his shoulders pitched forward slightly, his eyes intent and squinting against the glare, searching for rocks below the surface. He steered the boat around little tufts of island like a waiter making his way through a crowded restaurant. He made sweeping turns in the open water where there seemed to be no danger. “The quickest path between two points is not always a straight line,” he said, swerving to the left. “You can’t just head for that boathouse over there and hope to make it. There’s a lot you just don’t see out here.”

In an age when so many things change from year to year and constancy is only a dream, Dave Webster is one fixture that the summer residents of Great Pond can count on. He brings good news and bad, checks and bills, but he is there every day and that is enough.

One woman came down half-running with a wide grin on her face. A dog nipped at a dangling thread trailing from the hem of her faded flower-print dress as she made her way through the children’s toys and uncut firewood strewn across the yard. “The season starts when I see you come along, Dave,” the woman said, her hands on her hips.

“Yeah,” Dave replied. “Summer officially begins.”

Excerpt from “The Summer Mailboat,” Yankee Magazine June 1988

In 1943, the summer Dave Webster turned 15, he began delivering mail by boat on Great Pond, an 8,000-acre lake about 15 miles north of Augusta, Maine. He learned the route from his father, who earlier that year won the contract when the regular postman was drafted. It was the kind of work that sat well with Dave, partly because he could do it outside, partly because he could keep a close watch on the pretty girls who summered on Great Pond, but mostly because when you deliver mail on a lake in Maine you work for yourself.

For two summers Dave enjoyed his work. Then he volunteered for the Navy and shipped out to the Aleutian Islands. He regained control of the Great Pond route in 1950 and has delivered the mail over this same 35-mile stretch of water ever since, summer after summer, from the first of June to the last day of September. Postal officials in Boston know of no one in America who has been delivering the mail longer than Dave on what they call a “water route,” maneuvering his boat between the ledges and up to the mailboxes on the docks.

One of those boxes belonged to Ernest Thompson, the playwright who wrote On Golden Pond. He used Dave as a model for a character named Charlie, a mailman who went around saying “Holy Mackinoly.”

“I never said ‘Holy Mackinoly’ in my entire life,” Dave told me right away when I joined him last spring for the first run of the season.

A warm breeze out of the west rocked the boats tied to the dock, their bows squeaking against the old timbers. There was a faint chop on the water. Dressed in a white T-shirt and new dungarees cut off at the kneecaps, Dave walked ahead, carrying a batch of mail in a white canvas bin.

“We’ve got a hundred boxes out there now,” he said. “That’s four times as many as we used to have when my father first took the route on and probably twice as many as L.L. Bean’s brother Irving used to have when he delivered mail before us.”

He tucked the mail in the open bow of a 16-foot powerboat, then put his hands on his hips and stared out over the lake. He studied it, like a carpenter checking the grain in a piece of lumber. I said something about how he must know this lake better than anyone.

“I’m commencin’ to learn it,” he said. “Commencin’ to learn it.” With a turn of the key he started the engine, shifted into reverse, and we backed away from the dock.

Only a handful of these water routes survive in the Northeast. “I don’t make any money on it,” Dave told me with resignation. “But I’ve grown attached to it.” Five years ago he sat down with an accountant, and when they figured out all the extra costs of the mail route, it was clear Dave was losing money. Reluctantly he asked the Postal Service for a raise.

“If you got a job, you hang onto it,” he said. “I was trying to get an increase without them taking the route away. It wasn’t like I wanted top dollar. I just wanted to break even.”

The Postal Service gave him half of what he asked for, $6,200 a year, which figures out to about $4.50 an hour. “That’s if everything goes smoothly,” Dave pointed out. “If the mail boat breaks down somewhere on the lake, then two boats have got to be called out. One boat tows the broken-down boat in, and the other boat continues on with the mail. Somehow you’ve got to fulfill your obligations. I mean, people are depending on you.”

They were depending on Dave this morning. Women peeked from behind lace curtains in camp windows, checking and rechecking the lake while men puttered around in the yard, nailing a spare shingle on the woodshed or cutting wild grass away from the garden. Dave throttled back to an idle as he inched his way up to each dock. There he stood and balanced himself in the center of the boat, one hand gripping the steering wheel to steady the boat while the other reached for the mail. Everyone hustled down to the boat to scoop the mail out of Dave’s hand.

He smiled and answered their questions about who had returned for another season. To the summer residents of Great Pond, Dave is more than a mailman. He is the link connecting them and one of the elements that makes a community of a hundred separate cottages rimming the shore of a giant lake. A tax lawyer from Camden, New Jersey, still dressed in wingtip shoes, remarked, “If it wasn’t for Dave Webster, this wouldn’t be Great Pond.”

Back out on the water, Dave stood at the steering console, his shoulders pitched forward slightly, his eyes intent and squinting against the glare, searching for rocks below the surface. He steered the boat around little tufts of island like a waiter making his way through a crowded restaurant. He made sweeping turns in the open water where there seemed to be no danger. “The quickest path between two points is not always a straight line,” he said, swerving to the left. “You can’t just head for that boathouse over there and hope to make it. There’s a lot you just don’t see out here.”

In an age when so many things change from year to year and constancy is only a dream, Dave Webster is one fixture that the summer residents of Great Pond can count on. He brings good news and bad, checks and bills, but he is there every day and that is enough.

One woman came down half-running with a wide grin on her face. A dog nipped at a dangling thread trailing from the hem of her faded flower-print dress as she made her way through the children’s toys and uncut firewood strewn across the yard. “The season starts when I see you come along, Dave,” the woman said, her hands on her hips.

“Yeah,” Dave replied. “Summer officially begins.”

Excerpt from “The Summer Mailboat,” Yankee Magazine June 1988

In 1943, the summer Dave Webster turned 15, he began delivering mail by boat on Great Pond, an 8,000-acre lake about 15 miles north of Augusta, Maine. He learned the route from his father, who earlier that year won the contract when the regular postman was drafted. It was the kind of work that sat well with Dave, partly because he could do it outside, partly because he could keep a close watch on the pretty girls who summered on Great Pond, but mostly because when you deliver mail on a lake in Maine you work for yourself.

For two summers Dave enjoyed his work. Then he volunteered for the Navy and shipped out to the Aleutian Islands. He regained control of the Great Pond route in 1950 and has delivered the mail over this same 35-mile stretch of water ever since, summer after summer, from the first of June to the last day of September. Postal officials in Boston know of no one in America who has been delivering the mail longer than Dave on what they call a “water route,” maneuvering his boat between the ledges and up to the mailboxes on the docks.

One of those boxes belonged to Ernest Thompson, the playwright who wrote On Golden Pond. He used Dave as a model for a character named Charlie, a mailman who went around saying “Holy Mackinoly.”

“I never said ‘Holy Mackinoly’ in my entire life,” Dave told me right away when I joined him last spring for the first run of the season.

A warm breeze out of the west rocked the boats tied to the dock, their bows squeaking against the old timbers. There was a faint chop on the water. Dressed in a white T-shirt and new dungarees cut off at the kneecaps, Dave walked ahead, carrying a batch of mail in a white canvas bin.

“We’ve got a hundred boxes out there now,” he said. “That’s four times as many as we used to have when my father first took the route on and probably twice as many as L.L. Bean’s brother Irving used to have when he delivered mail before us.”

He tucked the mail in the open bow of a 16-foot powerboat, then put his hands on his hips and stared out over the lake. He studied it, like a carpenter checking the grain in a piece of lumber. I said something about how he must know this lake better than anyone.

“I’m commencin’ to learn it,” he said. “Commencin’ to learn it.” With a turn of the key he started the engine, shifted into reverse, and we backed away from the dock.

Only a handful of these water routes survive in the Northeast. “I don’t make any money on it,” Dave told me with resignation. “But I’ve grown attached to it.” Five years ago he sat down with an accountant, and when they figured out all the extra costs of the mail route, it was clear Dave was losing money. Reluctantly he asked the Postal Service for a raise.

“If you got a job, you hang onto it,” he said. “I was trying to get an increase without them taking the route away. It wasn’t like I wanted top dollar. I just wanted to break even.”

The Postal Service gave him half of what he asked for, $6,200 a year, which figures out to about $4.50 an hour. “That’s if everything goes smoothly,” Dave pointed out. “If the mail boat breaks down somewhere on the lake, then two boats have got to be called out. One boat tows the broken-down boat in, and the other boat continues on with the mail. Somehow you’ve got to fulfill your obligations. I mean, people are depending on you.”

They were depending on Dave this morning. Women peeked from behind lace curtains in camp windows, checking and rechecking the lake while men puttered around in the yard, nailing a spare shingle on the woodshed or cutting wild grass away from the garden. Dave throttled back to an idle as he inched his way up to each dock. There he stood and balanced himself in the center of the boat, one hand gripping the steering wheel to steady the boat while the other reached for the mail. Everyone hustled down to the boat to scoop the mail out of Dave’s hand.

He smiled and answered their questions about who had returned for another season. To the summer residents of Great Pond, Dave is more than a mailman. He is the link connecting them and one of the elements that makes a community of a hundred separate cottages rimming the shore of a giant lake. A tax lawyer from Camden, New Jersey, still dressed in wingtip shoes, remarked, “If it wasn’t for Dave Webster, this wouldn’t be Great Pond.”

Back out on the water, Dave stood at the steering console, his shoulders pitched forward slightly, his eyes intent and squinting against the glare, searching for rocks below the surface. He steered the boat around little tufts of island like a waiter making his way through a crowded restaurant. He made sweeping turns in the open water where there seemed to be no danger. “The quickest path between two points is not always a straight line,” he said, swerving to the left. “You can’t just head for that boathouse over there and hope to make it. There’s a lot you just don’t see out here.”

In an age when so many things change from year to year and constancy is only a dream, Dave Webster is one fixture that the summer residents of Great Pond can count on. He brings good news and bad, checks and bills, but he is there every day and that is enough.

One woman came down half-running with a wide grin on her face. A dog nipped at a dangling thread trailing from the hem of her faded flower-print dress as she made her way through the children’s toys and uncut firewood strewn across the yard. “The season starts when I see you come along, Dave,” the woman said, her hands on her hips.

“Yeah,” Dave replied. “Summer officially begins.”

Excerpt from “The Summer Mailboat,” Yankee Magazine June 1988

In 1943, the summer Dave Webster turned 15, he began delivering mail by boat on Great Pond, an 8,000-acre lake about 15 miles north of Augusta, Maine. He learned the route from his father, who earlier that year won the contract when the regular postman was drafted. It was the kind of work that sat well with Dave, partly because he could do it outside, partly because he could keep a close watch on the pretty girls who summered on Great Pond, but mostly because when you deliver mail on a lake in Maine you work for yourself.

For two summers Dave enjoyed his work. Then he volunteered for the Navy and shipped out to the Aleutian Islands. He regained control of the Great Pond route in 1950 and has delivered the mail over this same 35-mile stretch of water ever since, summer after summer, from the first of June to the last day of September. Postal officials in Boston know of no one in America who has been delivering the mail longer than Dave on what they call a “water route,” maneuvering his boat between the ledges and up to the mailboxes on the docks.

One of those boxes belonged to Ernest Thompson, the playwright who wrote On Golden Pond. He used Dave as a model for a character named Charlie, a mailman who went around saying “Holy Mackinoly.”

“I never said ‘Holy Mackinoly’ in my entire life,” Dave told me right away when I joined him last spring for the first run of the season.

A warm breeze out of the west rocked the boats tied to the dock, their bows squeaking against the old timbers. There was a faint chop on the water. Dressed in a white T-shirt and new dungarees cut off at the kneecaps, Dave walked ahead, carrying a batch of mail in a white canvas bin.

“We’ve got a hundred boxes out there now,” he said. “That’s four times as many as we used to have when my father first took the route on and probably twice as many as L.L. Bean’s brother Irving used to have when he delivered mail before us.”

He tucked the mail in the open bow of a 16-foot powerboat, then put his hands on his hips and stared out over the lake. He studied it, like a carpenter checking the grain in a piece of lumber. I said something about how he must know this lake better than anyone.

“I’m commencin’ to learn it,” he said. “Commencin’ to learn it.” With a turn of the key he started the engine, shifted into reverse, and we backed away from the dock.

Only a handful of these water routes survive in the Northeast. “I don’t make any money on it,” Dave told me with resignation. “But I’ve grown attached to it.” Five years ago he sat down with an accountant, and when they figured out all the extra costs of the mail route, it was clear Dave was losing money. Reluctantly he asked the Postal Service for a raise.

“If you got a job, you hang onto it,” he said. “I was trying to get an increase without them taking the route away. It wasn’t like I wanted top dollar. I just wanted to break even.”

The Postal Service gave him half of what he asked for, $6,200 a year, which figures out to about $4.50 an hour. “That’s if everything goes smoothly,” Dave pointed out. “If the mail boat breaks down somewhere on the lake, then two boats have got to be called out. One boat tows the broken-down boat in, and the other boat continues on with the mail. Somehow you’ve got to fulfill your obligations. I mean, people are depending on you.”

They were depending on Dave this morning. Women peeked from behind lace curtains in camp windows, checking and rechecking the lake while men puttered around in the yard, nailing a spare shingle on the woodshed or cutting wild grass away from the garden. Dave throttled back to an idle as he inched his way up to each dock. There he stood and balanced himself in the center of the boat, one hand gripping the steering wheel to steady the boat while the other reached for the mail. Everyone hustled down to the boat to scoop the mail out of Dave’s hand.

He smiled and answered their questions about who had returned for another season. To the summer residents of Great Pond, Dave is more than a mailman. He is the link connecting them and one of the elements that makes a community of a hundred separate cottages rimming the shore of a giant lake. A tax lawyer from Camden, New Jersey, still dressed in wingtip shoes, remarked, “If it wasn’t for Dave Webster, this wouldn’t be Great Pond.”

Back out on the water, Dave stood at the steering console, his shoulders pitched forward slightly, his eyes intent and squinting against the glare, searching for rocks below the surface. He steered the boat around little tufts of island like a waiter making his way through a crowded restaurant. He made sweeping turns in the open water where there seemed to be no danger. “The quickest path between two points is not always a straight line,” he said, swerving to the left. “You can’t just head for that boathouse over there and hope to make it. There’s a lot you just don’t see out here.”

In an age when so many things change from year to year and constancy is only a dream, Dave Webster is one fixture that the summer residents of Great Pond can count on. He brings good news and bad, checks and bills, but he is there every day and that is enough.

One woman came down half-running with a wide grin on her face. A dog nipped at a dangling thread trailing from the hem of her faded flower-print dress as she made her way through the children’s toys and uncut firewood strewn across the yard. “The season starts when I see you come along, Dave,” the woman said, her hands on her hips.

“Yeah,” Dave replied. “Summer officially begins.”