Time Passes Photographically in Boston

A photograph is essentially a split second in time captured on film or digitally, a record of what light revealed for the instant the shutter was open. Most of the time when you’re looking at a photograph, you are seeing something like 1/125th of a second captured from the eternal present as it passes before […]

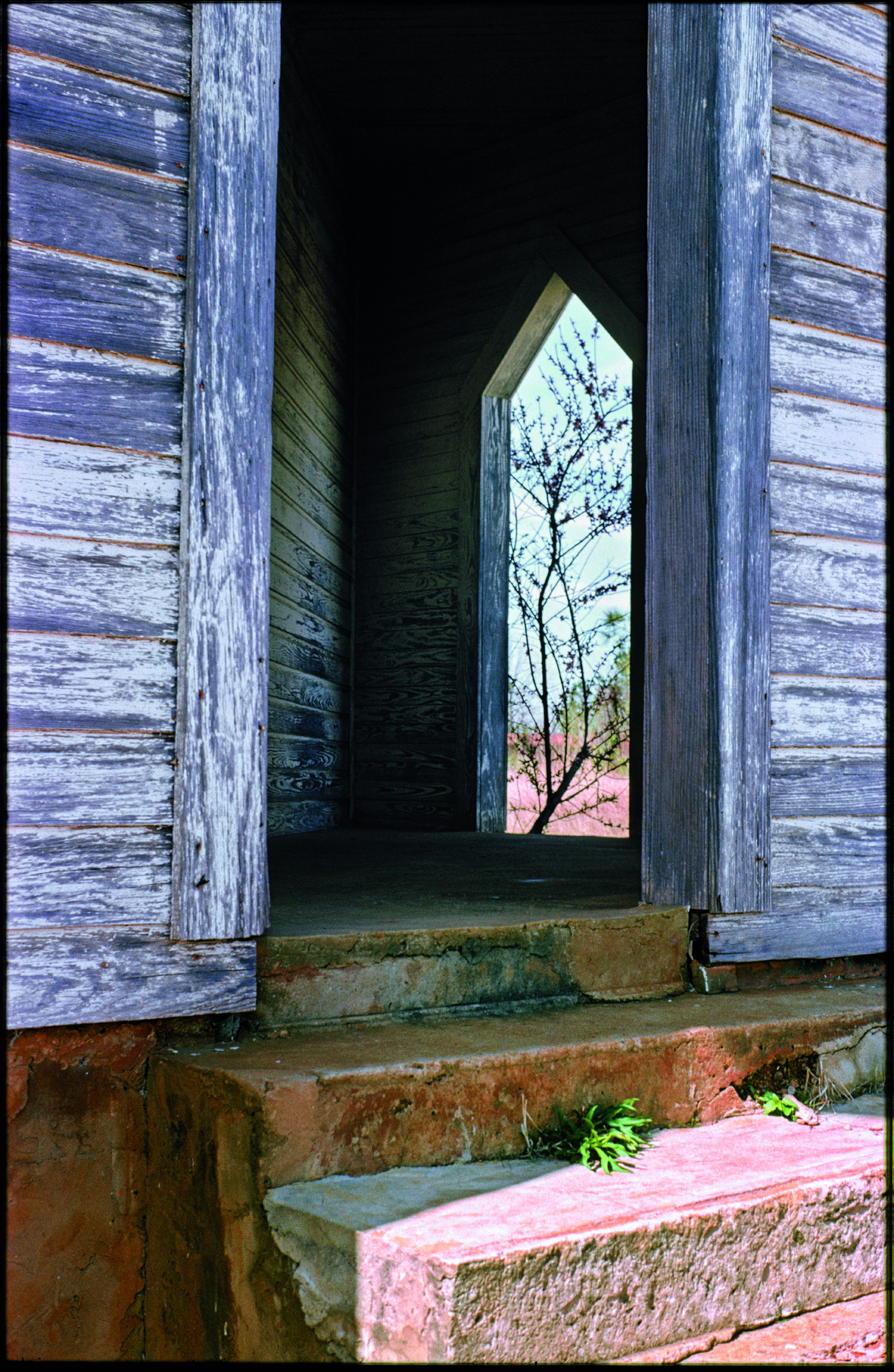

William Christenberry Images #3

A photograph is essentially a split second in time captured on film or digitally, a record of what light revealed for the instant the shutter was open. Most of the time when you’re looking at a photograph, you are seeing something like 1/125th of a second captured from the eternal present as it passes before the eye and the lens.

In Keeping Time: Cycle and Duration in Contemporary Photography (through January 25) at Boston University’s Photographic Resource Center, seven photographers focus variously on human, celestial, and photographic cycles, creating images that are visual records not of split second revelations but of temporal processes they have observed or conceived.

Like Eadweard Muybridge’s classic multiple-camera photo sequences of men and animals in motion, the photographs in Keeping Time operate at the intersection of art and science, their aesthetic value inexorably tied to the artists’ little experiments with time.

Stuart Allen of San Antonio, for instance, creates “Light Maps,” creating panoramic chromatic sequences that resemble minimalist paintings by recording the changing color of ambient daylight on a piece of white sailcloth.

Erika Blumenfeld of Marfa, Texas, that little high desert outpost of conceptual art colonized by Donald Judd, documented 93 days between vernal equinox and summer solstice by holding a hand-made light recording device up to the sun every day 6:17 p.m. She then created a looped silent video by sequencing her transparencies based on the timing of her own heartbeats. The result is a kind of hypnotic projection.

Rebecca Cummins of Seattle brings her own tablecloths to cafes and traces on them the shadows thrown by bottles and glasses. Then she photographs the linear records of where light has fallen, or failed to fall.

Chris McCaw of San Francisco uses military reconnaissance lenses and a hand-made camera to track the sun across the sky, overexposing vintage paper such the solar passage is virtually burnt into it.

Sharon Harper of Cambridge, Massachusetts, creates “Moon Studies and Star Scratches” by making multiple exposures of the night sky at set intervals on a single sheet of paper. The images that the star light paints read almost like the tracings of scattering electrons.

Matthew Pillsbury of New York City simply leaves his shutter open during the duration of a little human event such as a phone conversation or a movie to create “Screen Lives,” blurry vignettes of real life in which stationary objects remain in focus while human motion is smeared across the print.

Byron Wolfe of Chico, California, created his book Everyday: A Yearlong Photo Diary (Chronicle Books, 2007) by photographing an ordinary event every day between his 35th and 36th birthday. The images range from a bite taken out of a plum and a quilt hanging on a line to a child’s toy horse lying in the grass and the contents of a refrigerator.

Photographic Resources Center curator Leslie Brown might have included any number of other photographers whose work deal with the passage of time and light. Just a few blocks away, in fact, the Bakalar Gallery at Massachusetts College of Art is currently (through December 6) featuring William Christenberry Photographs: 1961 to 2005, a retrospective of 58 photographs by the legendary Washington, D.C. photographer, painter, and sculptor who has been returning to his birthplace in Hale County, Alabama, almost annually since 1968 to record the changes (and sometimes the lack of change) in the rural South. Christenberry’s photographs of modest Southern buildings over time have become an iconic statement about the passage of time in a place time forgot.

Photographic Resource Center, 832 Commonwealth Ave. Boston MA, 617-975-0600. Bakalar Gallery, Massachusetts College of Art, South Building, Huntington Ave, Boston MA, 617-879-7333.

Edgar Allen Beem

Take a look at art in New England with Edgar Allen Beem. He’s been art critic for the Portland Independent, art critic and feature writer for Maine Times, and now is a freelance writer for Yankee, Down East, Boston Globe Magazine, The Forecaster, and Photo District News. He’s the author of Maine Art Now (1990) and Maine: The Spirit of America (2000).

More by Edgar Allen Beem