Trouble on Mount Washington | A Missing Hiker, a Dangerous Rescue, and What Came Next

With freezing rain and snow closing in, a hiker’s grim texts set in motion a desperate White Mountains rescue effort.

On June 17th of last year, a Friday, at a little before 9 in the morning, Xi “Jesse” Chen texted his neighbor and longtime friend Dennis Gu about his weekend plans. A quiet, reserved man, Chen wasn’t one for bragging, but the 53-year-old industrial engineer had reason to feel excited about the upcoming three days. An experienced hiker who’d done extensive wilderness treks in Iceland and parts of Europe, Chen was most at home in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, which he’d begun exploring after moving to Massachusetts in the late 1990s.

Over the previous decade, especially, Chen had devoted many weekends to venturing north from his family’s home in Andover. Sometimes it was with his wife and three children in tow, but most often just with his teenage son, Kaiwen, who had the vim and vigor needed to complete the strenuous multiday climbs his father preferred. A patient observer who hiked with his camera always at the ready, Chen relished the chance to find secluded spots of beauty that he could share with others. As he did, Chen gave himself permission to let the work pressures that often draped over him fall away.

“He definitely seemed lighter when he was on those hikes,” says Kaiwen. “Even just waking up and having a cup of instant coffee, he’d really appreciate it. It was only instant coffee, but it was where he was. He was away from these other worries he might have had.”

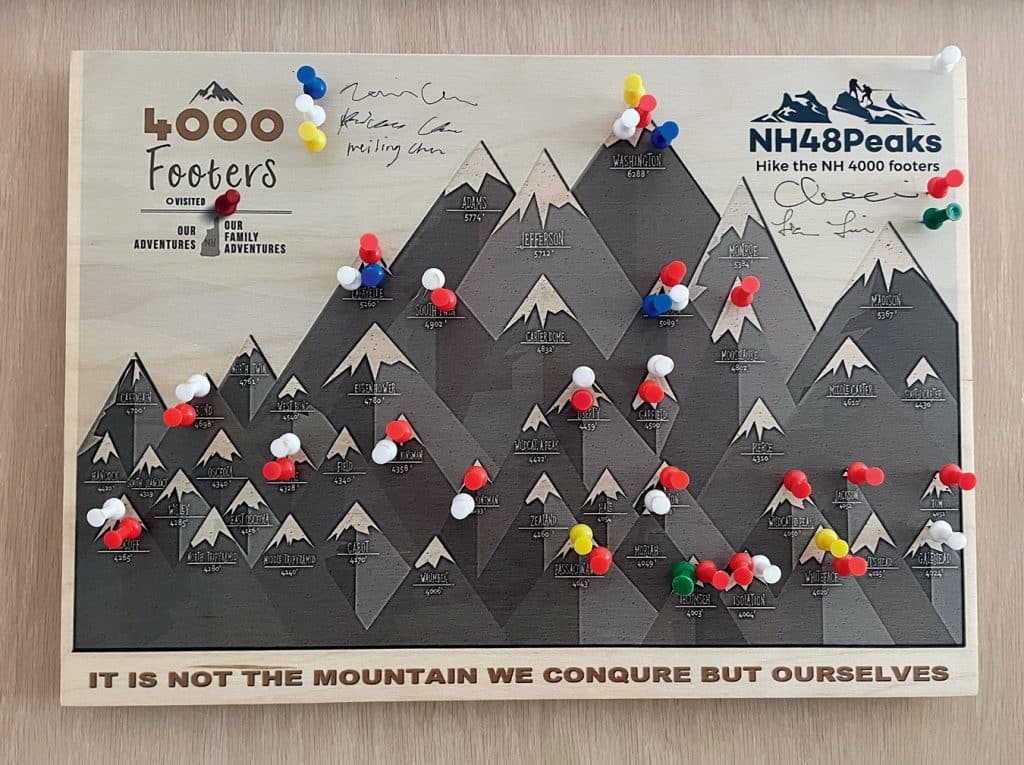

Hiking became central to Chen’s life even when he wasn’t on the trail. A devoted follower of the popular outdoor YouTuber Kraig Adams, he obsessed over finding the newest, lightest camping gear and kept a rolling list on his phone of the hikes he wanted to accomplish, including Mount Kilimanjaro. He also set a personal goal of climbing all 48 of the White Mountains’ 4,000-footers by 2025. On a wall in his kitchen, Chen even hung a map of those peaks, with color-coded pins for the ones he’d completed and the people he’d climbed with. By last June, he had already ticked off 21 of the climbs. Now, as he geared up for another trip to New Hampshire, he planned to knock off a few more.

Chen had set his sights on the Presidential Traverse, a rugged 20-mile journey that crosses seven 4,000-foot peaks, all named after U.S. presidents: Madison, Adams, Jefferson, Washington, Monroe, Eisenhower, and Pierce. One of the more storied routes in the Whites, the Presidential Traverse courses from peak to peak, taking hikers high above the treeline and rewarding them with views that extend deep across far northern New England. But that same terrain offers no relief from the elements, and the weather can turn ugly in an instant. Among serious White Mountain hikers, conquering the traverse is a true badge of honor.

Chen had scheduled his climb for Father’s Day weekend with the hopes that his son, a junior at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, could join him. But when Kaiwen couldn’t free up his schedule, Chen decided to go solo. About an hour before he left Andover, he texted a photo of his pack to his friend Gu.

I booked one year ago, supposed to go with Kaiwen, but he took summer classes and quite busy, Chen wrote. So I have to go by myself. He then added: Anyway this is a Loner Sport.

Awesome, Gu messaged back. Be careful when you are hiking by yourself.

No problem, came the reply. Still more relax [sic] than work.

By that evening, Chen had set up camp at the Madison Tent Site, a serene little spot enclosed by a grove of hardwoods off the Valley Way Trail at the base of Mount Madison. With his drone he made a 10-second video of the area, the camera rising above a proud-looking Chen to reveal the surrounding landscape. Chen did a quick edit of the footage, adding some music to the shot, then posted it on YouTube and sent the link to his family and Gu.

The following day, Chen rose early and set out on a 10-mile course to his base for the night: the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Lake of the Clouds Hut, just south of the highest mountain in the Northeast, Mount Washington. But a gray, wet start soon gave way to torrential downpours and eventually winter-like weather. With just a mile left in his trek, Chen—hammered by freezing rain, snow, and a minus-zero windchill—stopped moving near the summit of Mount Clay, the northern shoulder of Mount Washington. He wouldn’t get below treeline again until after midnight, when an elite mountain rescue team went to find him in conditions that, even by the standards of Mount Washington, were extreme for late June.

“These [Presidential] mountains are weird, because they’re tame most of the time,” says rescuer and veteran ice climber Michael Wejchert. “Something like Mount Washington, it’s unique because people try to climb it 365 days a year. It doesn’t have the worst weather, it’s not the tallest, and it’s not the steepest. But it has a version of all three of those things. And sometimes that mountain can fight back.”

Gu might not have shared Chen’s love of the outdoors, but he understood his friend’s ambitions. The two men’s bond went back to the mid-1980s, when both were physics students at the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology. Gu says his friend then was much like the person he later knew in Andover: hard-working with an appreciation for solitude.

The oldest of two boys born to archaeologist parents, Chen spent his formative years in Fuzhou, the capital of southeastern China’s Fujian province, but it was his early childhood in the countryside that he would recall most glowingly to his wife and children. He had loved to ramble around the fields that radiated out from his grandmother’s house, looking for wildlife, and watched with awe as older boys jumped fearlessly into a nearby river.

While Chen was at the University of Shanghai, his mother died suddenly of liver cancer. Until then, Chen had never imagined leaving his home country. Yet as China began to open up to the world, and he saw friends leave for the United States, he began to wonder what might be next for him.

He found it in an unlikely place: Kansas. Chen arrived at Wichita State University in January 1994 with $5,000 in savings to pursue a master’s in industrial engineering. As it happened, Wichita was also where his future wife, Lian Liu, had arrived nearly four years before from Sichuan province in southwestern China. A nursing student in her final year at tiny Bethel College, Liu met Chen at a house party hosted by the Chinese Student Association at Wichita State. Two weeks later, they began dating. Six months after that, the two married.

“I had friends who thought I was crazy—‘Why are you getting married so fast?’ they asked me,” says Liu. “But it felt right.”

In Wichita, Liu worked at a local hospital while Chen finished his degree. In 1996 Chen graduated and accepted a job with a flute manufacturer in Waltham, Massachusetts. The young couple found a small apartment in nearby Framingham, and Chen kept life in perpetual motion.

“He never wanted to just stay home,” Liu says. “We went to the Cape, we’d go up to Maine. He liked going to the movies, going out to eat, and he liked shopping, much more than me. We’d be out and he’d see something and say, ‘Why don’t you try that on? You’d look pretty in it.’ We’d get home with all this stuff and he hadn’t bought himself anything.”

In 2000 their first child was born, a daughter named Megan. Two years later Liu gave birth to Kaiwen, and in 2005 the couple’s second daughter, Meiling, arrived. Soon after, the Chen family moved to a five-bedroom colonial just a few doors down from his old friend, Dennis Gu, in Andover.

Even as the kids grew older and schedules became more complicated, Chen and Liu, a cardiac nurse at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, made time for family travel. There were camping trips to Maine, weekends on Cape Cod, more adventurous sojourns to the Grand Canyon and other national parks, and holiday treks through Europe. But even on family trips, Chen was always looking for extra adventure—when the family visited Iceland a few years ago, for example, he and Kaiwen arrived there a week early so they could hike and camp along the 34-mile Laugavegur trail.

“He was always looking for ways to challenge himself,” says Kaiwen. “Whether it was his work or the kind of hikes he wanted to do, he never wanted to feel like he was stagnating. And once he set his mind on something, he did everything in his power to actually do it.”

At 9:44 on the morning of June 18, Xi Chen took a series of short selfie videos atop Mount Madison, the first of the four presidential peaks he planned to traverse that day. In several of them he beams widely from beneath the hood of his jacket. The scene around him, however, is a stark contrast. The morning is gray, the peak shrouded in fog, the wind snapping Chen’s outer shell.

Over the next several hours, as Chen made his way up and over the boulder-strewn tops of Adams and Jefferson, a steady rain fell. At 2:50 p.m., Chen stopped briefly to text his wife: Got wet, three miles from any civilization. A bit concerned [about] hypothermia. Chen, who’d set his phone so Liu could track his general progress, then added, Keep an eye on my location.

At 4:26 p.m. Chen texted again. Heading [to] Mt. Washington or Lake in the Clouds hut.

Liu, who had recently returned from picking up Kaiwen in Worcester, felt her worry turn to fear. It’ll get dark early with the weather, she texted back. Let me know when u get there.

Chen replied: If I stop moving then in trouble.

Another hour passed before Liu heard from her husband again. By then, the weather had taken a turn for the extreme. On the summit of Mount Washington, gusts of up to 80 mph were driving the windchill down to 5 below. Sleet and snow had descended across the Presidential Range. Not even the best rain gear could have kept Chen dry, much less warm.

In all probability Chen was already suffering from hypothermia, which strikes when your core temperature drops below 95°F. As it attacks the body—forcing it to shiver excessively and reduce blood flow to the skin and extremities, to protect vital organs—it also attacks the mind. Causing memory loss, incoherence, disorientation, and sheer exhaustion, it can complicate a person’s ability o get help or find safety. At its most extreme, hypothermia can even trick the victim into feeling overheated, causing them to shed clothing.

It’s unclear exactly when Chen stopped walking, but at 5:30 p.m., just a mile from the Lake of the Clouds Hut, he sent out a desperate text to Liu. In trouble. Can’t move.

Do I need to call rescue? she asked.

Yes, he replied at 5:47. Could die.

Liu immediately dialed 911, but she was told that without her husband’s exact location, no rescue could be mobilized. As Liu urged her husband to message or call 911, Kaiwen sprang into action, taking the general location that his father’s phone had shared and using Google Maps’ satellite view to get a fix on his father’s approximate longitude and latitude. Liu relayed that information to a 911 dispatcher, who told her an officer with New Hampshire Fish and Game would call her back.

As Liu waited for the call, she tried again to reach Chen. When he didn’t pick up, she texted, pleading with him again to message 911 to solidify his location. Called 911, she wrote. They want you to call, or text 911 though I told them latitudes/longitudes. She waited a few minutes more, then: Are you awake?

Several minutes passed before Chen messaged his wife for the last time:

I am lost. Need help.

When Lieutenant Mark Ober of New Hampshire Fish and Game received a report at 6:34 p.m. of a missing hiker near Mount Washington, it had already been a long evening. A few hours earlier, he’d coordinated the rescue of a group of hikers who were experiencing hypothermia near Mount Madison. Now, Ober was stationed in his truck in Shelburne, overseeing the rescue of an injured hiker on Mount Hayes by three of his department’s conservation officers.

For nearly two decades, Ober has been in charge of the state’s rescue operations in the northern White Mountains. It’s the heart of a busy region for hikers: Just a day’s drive from places like Boston, New York City, and Portland, Maine, the White Mountain National Forest attracts more than 6 million visitors a year. In a given year Ober fields some 80 emergency calls, though not all require a rescue effort.

“You get people here in the summer who are literally just tired and want to be carried down,” says Ober. “Or they’ve lost a shoe, or a sole has come off a sneaker, and can we hike some new boots up to them? Or they didn’t bring a headlamp or flashlight and they’ve underestimated the time it’s going to take them to make it down. If it’s summer and the weather is nice, I’ll tell them, ‘You’re going to spend the night, because we’re not coming to get you.’”

For true emergencies, though, Ober has a choice of different teams to deploy. In the summer and early fall he leans on his department’s own specialized group of conservation officers or the region’s two main volunteer outfits, the Androscoggin Valley and Pemigewasset Valley search-and-rescue squads. But when the situation calls for navigating harsh winter weather above treeline—where both conditions and terrain can be especially treacherous—he turns to the “special forces” of the Whites: Mountain Rescue Service, or MRS.

Composed of some of the world’s most elite guides and climbers, MRS was born in 1972 as a response to the region’s growing popularity and the increasing number of dangerous backcountry rescues that came with it. Fatalities in the Whites were nothing new—the first reported hiking death on Mount Washington happened in 1849, and 77 additional lives had been lost on the mountain by the time MRS was founded—but pressure to prevent them had reached a tipping point. A coalition of officials from the Appalachian Mountain Club, Fish and Game, and the U.S. Forest Service came up with an innovative plan: Build a dedicated rescue operation with the growing number of young, expert climbers who had moved to the White Mountains. It was just a matter of months before the newly formed MRS proved its worth.

“There was a guy in just his bathing suit who had decided it would be a good idea to hike Whitehorse Ledge,” says Rick Wilcox, a world-renowned ice climber and MRS cofounder who led the organization from 1976 to 2016. “A few of us went over there, and there were these firemen standing around at the bottom, looking at each other and this climbing rope they had. I went over to the chief—‘Hey look, we are a part of this rescue team that can help you.’ He kind of brushed us off. ‘Nah, we got this.’ Then an hour passed and nothing had happened. I went back up to him and said, ‘Give us 15 minutes and we can get that guy down.’ That’s what we did, and that really started things off for us.”

In the half century since, MRS—whose 40-member team spans generations of climbers—has led more than 350 missions. There’s nothing glamorous about being a part of the crew. You’re on call 24 hours; many rescues, especially the most complicated ones, happen at night; and outside of a free ski pass to the local mountains, there’s no compensation.

“Climbers take care of other climbers, and that means anybody who goes into the mountains,” says Joe Lentini, a member of MRS since 1976. “I’m still a climber and I love the mountains, and as long as I’m able to help, why wouldn’t I do this work?”

Shortly after receiving the 911 dispatch, Ober called Lian Liu. He told her that a team would be assembled to find her husband, but that it might take a few hours before the rescue could begin. MRS crew members were scattered around the White Mountains region, equipment needed to be gathered, and it would take time to reach the most viable trailhead—which happened to be just below the summit of Mount Washington. And given the conditions, he couldn’t guarantee they’d even reach Chen. “We’ll do our best to rescue your husband, but not at the cost of the rescuers’ lives,” Ober said.

Ober then contacted Jeff Fongemie, vice president of MRS and lead snow ranger on Mount Washington. At 7:26 p.m. Fongemie sent out a rescue request to all MRS members through a WhatsApp text:

We’ve been asked by Fish and Game to get a hypothermic hiker off the summit of Mt. Clay to the Auto Road. It’s currently 32 degrees [with] freezing rain and northwest winds 50 to 60 miles per hour, with rain turning to snow. We are needed for this non-technical but nonetheless challenging rescue.

One of the first to respond was MRS president Michael Wejchert. A 35-year-old writer and climber who lives in North Conway with his wife, Alexa Siegel, a nurse and MRS team leader, Wejchert had just returned home from the grocery store when Fongemie’s text appeared on his phone. He immediately began pulling together supplies—stocking a couple of thermoses with hot Gatorade, stuffing extra clothes, including a dry suit, into a pack. Then he met up with three other MRS volunteers at International Mountain Equipment, an outdoor gear retailer that Wilcox owns in North Conway, where MRS keeps a cache of essential rescue gear such as sleeping bags, wilderness stretchers, and makeshift tents.

By 9:25 p.m. Wejchert was at the base of the Mount Washington Auto Road with his five-man team: Ryan Driscoll, Tim Doyle, Joe Klementovich, Charlie Townsend, and Steve Larson. Because freezing rain coated the upper reaches of the auto road, Ober had phoned for a truck with chains from the Mount Washington State Park crew to ferry the rescuers to just south of the summit. Klementovich and Townsend climbed into the cab while Driscoll, Wejchert, and Larson lay down in the bed and covered themselves with a tarp to fend off the rain.

“We’re bouncing around with no idea where we were,” Driscoll recalls. “Then the truck stopped and I remember hearing, ‘OK, this is where you guys get out.’ We pulled that tarp off and the rain was just pouring down. I looked around for a second and thought, This is going to be pretty bad.”

Waiting in Andover for word about the rescue seemed excruciating to Lian Liu, who wanted to be as close as possible to her husband. So she told Kaiwen and her younger daughter, Meiling, that they would drive to North Conway and find a hotel room. She phoned Dennis Gu to tell him the news and asked him to pick up her other daughter, Megan, after she finished work in Boston, and bring her home, where Liu’s sister would eventually meet her.

Meanwhile, Kaiwen pulled out his winter hiking gear. If the rescue team couldn’t get to his father, then he would. Maybe he didn’t have the strength to get him back down, he reasoned, but he could at least bring his temperature back up by getting him inside a sleeping bag with dry clothes on and pocket warmers stuffed around him. Kaiwen showed Liu a map. “If we go up the Mount Washington Auto Road, we can pick up a trail that’s a mile from where Dad is,” he told her. “You can stay in the car while Meiling and I go find him.”

Liu stayed quiet. She understood her son’s desperation but knew she couldn’t allow her children to put their own lives in danger. As Kaiwen continued gathering his equipment, she decided to not talk about the idea until they reached North Conway.

Shortly after Liu and her children left Andover, she received a call from Ober letting her know a rescue team had been mobilized. Relief washed over her. A plan was in place to find her husband. She wouldn’t need to talk Kaiwen out of a search. She told herself her husband would be OK. Maybe he was injured, she thought, but he was going to get off that mountain, and perhaps in a day or two he would be home. She repeated this hope inwardly as she drove. Kaiwen stared stoically ahead; his sister cried softly in the back seat.

Shortly after 10 p.m., they arrived in a rainy North Conway. Liu pulled into the parking lot of the first hotel she found and reached for her phone. Are u awake? she texted her husband. We arrived in North Conway now.

Then she called Ober. He had more good news: The MRS team was hiking to her husband’s location.

Wejchert and the others moved briskly in single file. Their course was a quick descent along the Gulfside Trail, the northern Presidentials’ main hiking artery and the route Chen had seemingly tracked since leaving the top of Madison. From the moment he stepped out of the truck, however, Wejchert was cursing himself for wearing glasses instead of contacts. With freezing rain pelting the lenses, he took them off and positioned himself in the back of the line, allowing his headlamp and the lights of those in front of him to guide him over the ice- and snow-covered terrain. The group moved largely in silence so they could concentrate on their footing.

At about the one-mile mark, Doyle and Driscoll, who had taken the lead and were tracking the group’s position by GPS, saw that they were coming up on Chen’s approximate location. They motioned to the others to begin looking for signs of him—a flickering headlamp, perhaps, or a stray piece of gear. Seconds turned to minutes as they pushed farther north on the Gulfside before circling back to where it junctions with the Jewell Trail. It was there that the men finally spotted Chen, about 15 feet off the path. He lay on his back, unconscious, his bare hands clenched on his chest. He was wearing his puffer jacket, an outer shell, rain paints, and boots. He did not have a hat on. Nearby were the scattered contents of his pack, including his tent, which he may have tried to set up for shelter.

After Doyle, a trained EMT, did a quick assessment of the unresponsive Chen, the crew worked quickly to get him into a sleeping bag, wrap him tightly with a tarp, and strap him down on the rescue stretcher. At 11:03 p.m. the squad began to carry Chen to the Mount Washington summit. Minutes later, they were joined by a second team of six Fish and Game conservation officers and three more MRS members.

The expanded team hiked uphill through 80 mph winds and steady freezing rain. Crews of six carried Chen for short stretches, switching off to conserve energy. For the final push to the summit, the team followed the tracks of the Cog Railway. At 12:45 a.m. they reached a waiting state park truck. Just over a half hour later, Chen was loaded onto an ambulance at the base of the Mount Washington Auto Road and sped 19 miles to the Androscoggin Valley Hospital in Berlin.

Lian Liu was already at the hospital when her husband arrived shortly before 2 a.m. Concerned about Covid and still not allowing herself to even consider that her husband might not survive, she had come alone, leaving Kaiwen and Meiling at the hotel. In the ER, Chen was settled onto a bed, his arms strapped down, a CPR machine on his chest. At the same time, a respirator machine worked to get oxygen into his body, as he wasn’t breathing on his own. His core temperature hovered in the 60s. Liu waited outside his room for a few long minutes before the doctor invited her in. “It doesn’t look good,” he warned her.

Over the next two hours the ER team worked frantically to revive Chen. Heat lamps surrounded his bed, and he was hooked to an IV that circulated warm saline solution through his body. As the doctor and nurses labored, Liu sat quietly by her husband’s left side, her hands clutching his, her head bowed and pressed down against them, as though in prayer. Increasingly desperate to get Chen breathing, the team tried to intubate him but couldn’t unlock his jaw. As a last-ditch effort, they performed a tracheostomy, but his condition never improved. He didn’t even have a viable pulse by then.

Shortly before dawn, the doctor approached Liu. “Do you want us to continue?”

Liu told him she needed more time. “I can’t do anything until my kids are here,” she said. Liu called her sister and asked her to drive Megan north and then bring all three of her children to the hospital.

As a nurse, Liu understood what she was seeing and knew what it meant, but as she waited for her family to arrive, she veered between hope and despair. She made calls to the major hospitals in Boston to see if she could have her husband transferred—though without a stable pulse, Chen couldn’t be moved. But she also thought about what survival might look like for Chen, a man who prided himself on his physical fitness. He had told his family that if he were in an accident that left him dependent on others, he didn’t wish to be kept alive. Liu began to realize that even her husband’s best-case scenario wouldn’t be what he wanted, and that she would have to carry out his last wishes. “I needed to advocate for him,” she later said.

It was a little before 9 on Sunday morning when an exhausted Liu greeted her children in the ER lobby. Then she led them to Chen’s bedside, where they all held his hands and said their good-byes.

By the end of the day, most of the MRS team had learned of Chen’s death. He was one of 21 hiking fatalities in the White Mountains in 2022, including three right at the end of the year. For rescuers like Wejchert, their work can immerse them in a person’s worst moment—maybe even the final moments—and the impact of that can linger long after the exhaustion and adrenalin have disappeared.

“Many people that next day just go to work at their jobs, whether it’s guiding or banging nails,” says Wejchert. “But it doesn’t mean they’re not thinking about it. They’re just trying to keep going. When you’re [on the rescue] you kick into this gear where you don’t humanize the situation, in a way. You’re in this mode of doing what you have to do. It’s only afterward where you start to feel sad. You read a news story about who they were, the family they had.

“It’s hard, but we do this for a reason. There are people who need our help. I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a situation where somebody on the team was like, ‘I’m sick of these people.’ I think when you first start climbing or hiking you think, Oh, that person’s an idiot for [making that mistake]. You feel like you’ll never be that person. But we’ve all been around the block a few times. We know it either has been us, or it could easily be one of us.”

Aweek after Xi Chen’s death, a local hiking group of Chinese-Americans completed the entire Presidential Traverse in their late friend’s honor. Over the course of the 16-hour trek, the hikers placed a framed photo of Chen at different cairns and took pictures of it to share with Liu and her children.

Liu showed me a few of the snapshots when I met her last November at the family home in Andover. It was the first of several meetings, including interviews with her two oldest children. Like their mom, Kaiwen and Meganoften spoke in the present tense when discussing their father. “It still doesn’t feel real,” Liu said at one point, quietly.

Chen’s presence in the house was impossible to ignore. His vast collection of hiking gear was still clustered in the basement. Framed pictures from hikes and family trips hung on many of the walls. On a coffee table were photo albums he’d meticulously constructed. One had a cover photo of his three young children, smiling and piled on top of each other, at a rest stop just off New Hampshire’s Kancamagus Highway. “Foliage camping trip on Columbus Weekend is a new family tradition,” read one of the captions inside. In the kitchen there still hung the map of Chen’s completed 4,000-footers. “You can see he only did two of those with me,” Liu said with a small laugh.

Over the course of our conversations, Liu returned to the questions she kept asking herself. How had a man who was so meticulous gotten himself into such a dangerous situation? Why had he waited so long to ask for help? What else could have been done to save his life? There are no answers, of course. No easy ones, anyway.

And yet, there have been some moments of comfort. Discovering photos from a favorite family trip. Remembering how her husband loved to watch American Idol and how he playfully insisted on cueing up the song “Home” by contestant Phillip Phillips whenever the family returned from a vacation. Recalling how a food-obsessed Chen would keep his family waiting no matter how hungry they might be so he could find the perfect restaurant.

Or this:

A few years ago, Chen told Megan that when he died he hoped to be buried by a tree. Last fall, as the family visited a nearby cemetery, they came across a pretty little spot that sits a bit off on its own and is slightly shaded by a red maple. It was as though the plot found them, says Liu. Later this year it will become Xi Chen’s resting place. A pretty little spot that’s drenched in sunshine and fresh air. The kind of place he always relished finding.

See More:

7 White Mountains Hiking Safety Tips From a Longtime Guide and Mountain Rescuer