Low Tide in the Hills

Down on the coast, they understand the tides. They live by the tides–and not only as a practical matter for seagoing folk, but more subtly, as well. Twice a day, the harbors, bays, and coves fill and empty, fill and empty. The edge of the continent comes close, then pulls back. Down on the coast, […]

Down on the coast, they understand the tides. They live by the tides–and not only as a practical matter for seagoing folk, but more subtly, as well. Twice a day, the harbors, bays, and coves fill and empty, fill and empty. The edge of the continent comes close, then pulls back. Down on the coast, the everyday setting is bracketed by the daily ebb and flow of the sea.

There is also a tide upcountry, in the hills, but its nature is different. The hill-country tide isn’t on a day-to-day cycle. To the north and west, far from the shore, the tides project themselves over the seasons; they’re an image of the progress of winter, spring, summer, fall. Inland, the flood tide of autumn comes in early September with the peak of growth in woods, fields, waysides, and gardens. The tide ebbs gradually, then more quickly through the weeks of autumn color and past them into November. Sometime in late November, early December, the tide of the year is finally out. The hayfields are mown; the cornfields are cut down to stubble. The season’s shallows, bars, and ledges lie bare, stretched out before the onlooker all the way to winter.

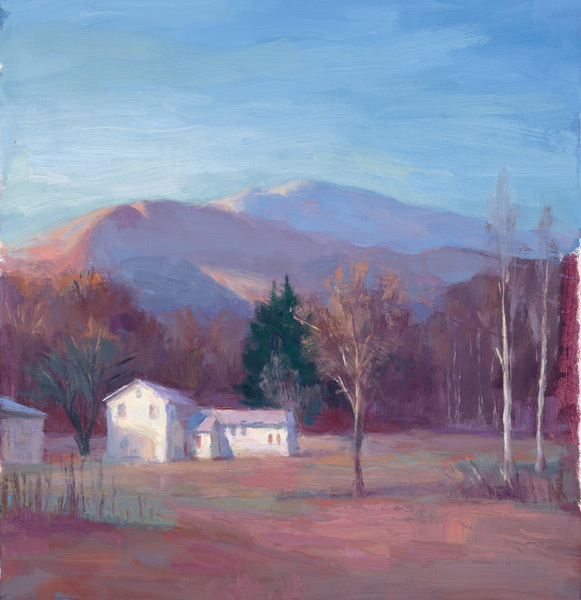

The hill-country tide in the fall doesn’t work its force on the ocean. Its medium isn’t water, but light. The warm, dusty light of summer and early fall, suffused with the colors of the red and yellow leaves, withdraws from the skies, leaving a deeper, inkier blue, indigo succeeding upon the lighter cerulean of the warmer months. Clouds gather. Under the new, darker sky, the hills seem to pull in a little closer, except where a break of sun, illuminating a section of the landscape, emphasizes its scale, its distances.

The ebbing of the light at this season is of a piece with other changes. The tides in the hill country are in people’s lives and minds as much as they are in the daylight, in the weather. At this time, the verge of winter, the flow and flux of the region’s inhabitants is at its lowest. Whatever birds were going to head south for the winter have long since left. Among their human neighbors, the summer visitors and the admirers of foliage are gone. The skiers and holiday travelers have yet to arrive. The fall chores of putting away, battening down, covering up, are done–or if they’re not, they’d better be soon. The land lies deserted, unused, a broad tidal flat where those who are still around and so inclined may contemplate this season’s subdued but distinctive beauty.

Low tide in the hills is no more than a moment in the year, but it’s not hard to witness, given the right timing. For the past 10 or 12 years, I’ve had a good look at it, thanks to a little trip I have occasion to make every fall at this time. Just as November clicks over to December, I find myself up north, driving across the top of New England on good old Route 2. U.S. 2 is one of the great unsung highways of pre-Interstate America. You can pick it up in Houlton, Maine, and ride it clear to the Pacific, just north of Seattle. Seattle is a good town, no doubt, but it’s a long way away. I prefer to do my traveling without leaving home.

I get on Route 2 in Bethel, Maine. I head west, through Gorham, New Hampshire, and over the mountains to St. Johnsbury, Vermont. It’s a matter of some 75 miles, mainly two-lane, the eastern half of the way running along the valley of the Androscoggin River. Then on the left, south, the White Mountains: Mount Adams, Mount Washington, often showing a light dusting of snow on their upper slopes. At this time of year, I have the road pretty much to myself. Driving through the big valley around Jefferson, New Hampshire, I might be an out-of-season insect, making its lonely way across the deep end of a swimming pool that’s been drained for winter. The country, a crowded, bustling vacationland in summer, is pretty well emptied out. The towns and villages, the big old hotels and other lodgings, the popular tourist attractions, are untenanted. All along the way, the countryside is plain, stripped–quietly, patiently waiting to receive the coming winter. In St. Johnsbury I turn south, leaving the tideland, under its lofty purple sky, to itself for another year.

The autumnal tides of light, cloud, and shadow that annually visit and revisit the hill country are figurative tides. They’re a matter of feelings, of perceptions. Low tide in the hills can’t be measured, it doesn’t obey the almanac, but it makes a welcome passage in the outdoor year, for those who will attend.