The Encyclopedia of Fall: D Is For Dirt Roads

I hewed the road out of wilderness in 1779 with my pickaxe as one of Colonel Hazen’s men. I took over the yoke in 1789 when one of the oxen sickened, pulling the sled the last hundred miles to Wolcott. I herded a thousand turkeys over to Boston in 1826, making twelve miles a day […]

I hewed the road out of wilderness in 1779

with my pickaxe as one of Colonel Hazen’s men.

I took over the yoke in 1789 when one of the oxen sickened,

pulling the sled the last hundred miles to Wolcott.

I herded a thousand turkeys over to Boston in 1826, making twelve miles a day at best.

I heard the motorcar sound from a growl to a roar carrying folks who were not my kin,

and I drove my own Jeep eighty-eight rutted miles a day delivering mail to this town.

I’ve known dirt roads:

Muddy, dusty dirt roads.

All my roads began as dirt roads.

This condensed history, which emulates Langston Hughes’s poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” is based on some of the people and events making and taking the roads of Vermont. There are still 8,740 miles of dirt and gravel roads running under canopies of sugar maples, skirting lakes, bordering fields, presided over by rogue apple trees at intervals that match streetlights in more urban districts.

The Bayley-Hazen Military Road, commissioned by General Washington, was one of the first roads hewn into the sparsely settled Northeast Kingdom. A decade later, Seth Hubbell brought his family up from Connecticut, under such harsh luck and conditions as to have broken a lesser man’s resolve. Some 220 years later, more than half of Vermont’s 15,820 miles of roads are still in their original form: dirt. Throughout my town in northern Vermont, whether the roads are named for waters (Black River, Seaver Brook, Page Pond, Creek) or hills (Morey, Ketchum, East, Denton) or features (King Farm, Mud Island, Lost Nation, Guy Lot), almost all are dirt. Dirt. Dirt. Dirt.

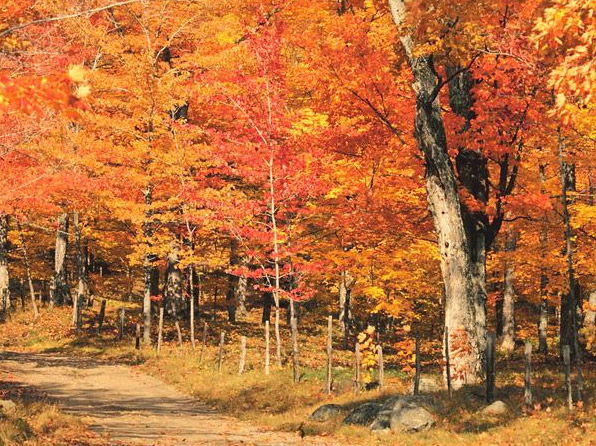

They are man’s handwritten note on the planet, drawn in graphite, against the brilliant crayonings of autumn leaves. Whereas paved roads, like slick prose, make it easy to proceed, roll by at a cool 65 mph, dirt roads are more like written dialect: tricky; cruise control is moot; you earn your translation through patience. Though most of us use these old roads to commute to jobs in other towns, our rural mail carrier spends eight hours feeding each of the 369 mailboxes on her route. Her workplace is made of silt and silica, ground-up granite and melted-down mountains, and she can only go 25 mph on it after it rains.

I’ve known dirt roads:

I ran with my dog on the Bayley-Hazen Road

where it caresses the side of Caspian Lake.

I walked my cow over to South Albany Road and handed the rope to her new owner.

I stopped the car for seven partridge chicks sprint-trickling across to their mother.

I heard the town grader sounding from a growl to a roar nearing my dooryard,

and I bicycled eight miles, leaving a slender dust-ghost in my wake.

I’ve known dirt roads:

Primordial, washboardy dirt roads.

I live on and beside a dirt road.

Read more about Autumn A to Z in the September/October issue of Yankee Magazine

Read more about Autumn A to Z in the September/October issue of Yankee Magazine

Julia Shipley

Contributing editor Julia Shipley’s stories celebrate New Englanders’ enduring connection to place. Her long-form lyric essay, “Adam’s Mark,” was selected as one of the Boston Globes Best New England Books of 2014.

More by Julia Shipley