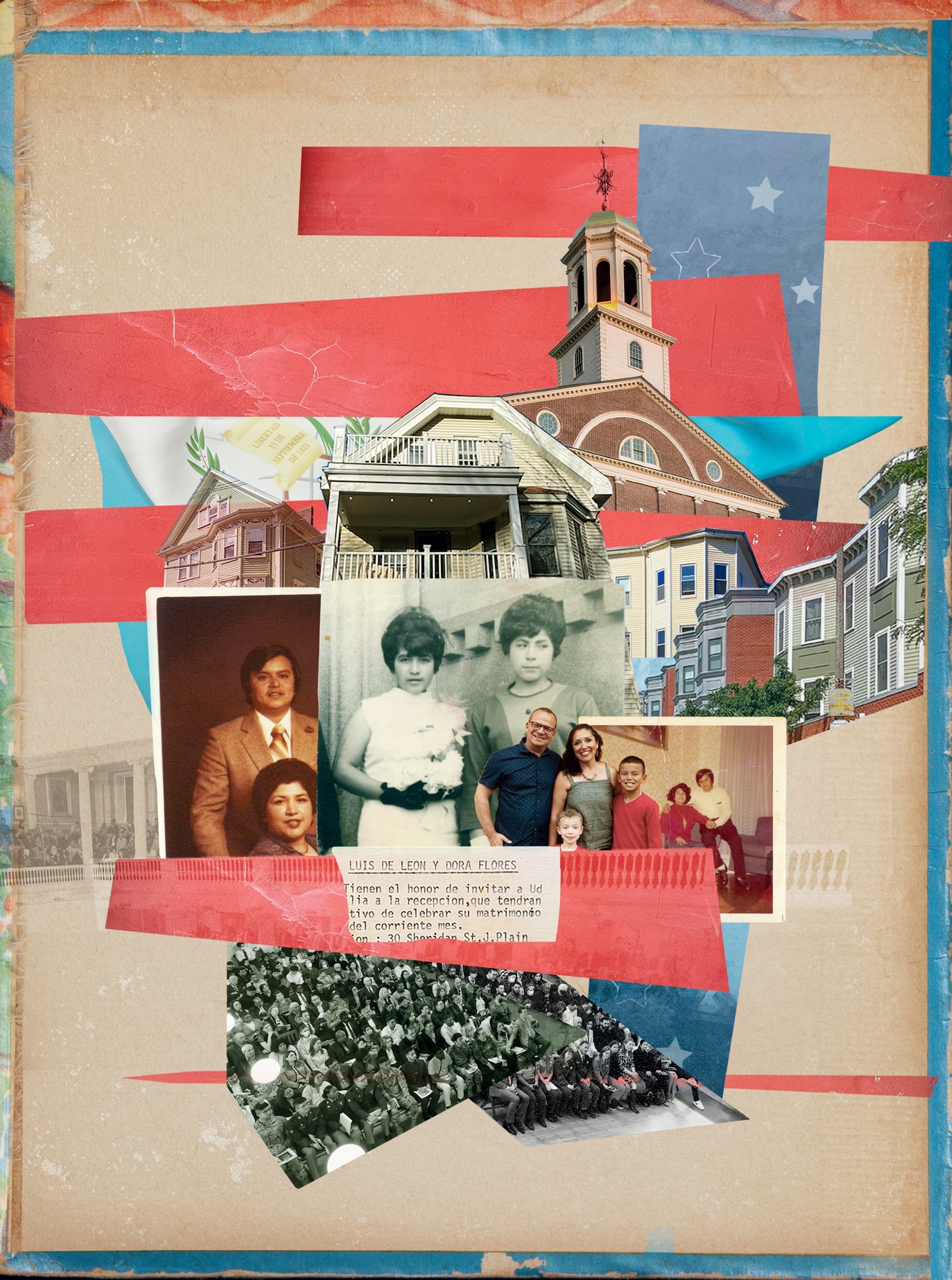

Family photos and scenes around Boston evoke the immigrant story of author Jennifer De Leon’s parents.

Photo Credit : Photo illustration by Dana SmithBy Jennifer De Leon

On this sunny October day in Massachusetts, the blue sky stretches wide as my parents, husband, two young sons, and I head to Boston, a city that holds so much history in its pocket—our history.

When my mother was 18, her former elementary school principal loaned her the money for a one-way flight from Guatemala City to Los Angeles. There, she learned English by memorizing five words a day, worked as a live-in nanny for four years, and met my father. He, too, had come from Guatemala, but his time in California was—he believed—temporary. His main goal was to make enough money to buy a motorcycle, then head back home.

As with any good story, there was a plot twist: Soon after they were engaged, my father got a job offer he could not turn down (driving trucks, the most money he had ever made); only it was in a place called Boston, Massachusetts. And so our family map, like the far-reaching sky above us today, widened. It was in this part of the world that my parents married, became U.S. citizens, and raised three daughters.

As we make our way down the Massachusetts Turnpike, my 10-year-old son practically yells from the back seat (a little too loud, because he wears headphones), “Where are we going again?”

“Faneuil Hall,” I reply.

“So, we’re going to see a hall. Wow.”

“Don’t be like that. It’s where your abuelos became citizens.”

“Oh, yeah,” my mom says, sugar in her voice. “I remember that day. Verdad, Luis?”

My father, wearing a jacket zipped up to the neck and a Patriots hat, simply nods. I watch him in the rearview mirror through my white-rimmed sunglasses. Always, I drive. Otherwise I get carsick, a trait I passed on to my boys. They have playlists and lollipops to distract them. I have the road ahead—and stories. Always stories.

Like how my parents were married in a civil ceremony in a courthouse in Manchester, New Hampshire, instead of Boston because they were afraid that officials at City Hall would ask too many questions about their legal status. In the mid-1970s, immigration raids were common, and their paperwork had not yet been finalized. They could not imagine being sent back to their home country like returned mail. Safer to quietly marry just over the border, in New Hampshire.

In the car, my mother loves to share stories. She goes on about fulano (so and so) this, and fulana that, sharing random anecdotes about people I vaguely know. But today, the stories spin on the axis of memory. The day my parents became U.S. citizens in Faneuil Hall. And how, aside from the births of their children, it was the most important day in their lives—that, and when they got married.

First, Faneuil Hall. I admit, I didn’t always know the story. But raising kids of my own is a glorious prompt, really, to hear my parents talk about their past. How when my mother first came to America, she longed to speak Spanish so much that she would open the Yellow Pages, find a random Spanish surname, and dial the number. And how my father used his first paycheck in Boston to buy a winter coat. I love that my boys are inheriting these details, and I hope they will remember this day trip in particular.

After we park, we step onto the sidewalk and stretch a little. Something about autumn in New England always makes me sit up straighter, lean forward, a whiff of cinnamon and sharpened pencils permanently in the air. We are here. In “the city.”

“Be careful!”

“Hold his hand!”

“Did you lock the car?”

I am.

OK.

Yes.

No matter how much time passes, it seems, I am still my parents’ daughter.

And, a mother. “I’m hungry,” my 5-year-old announces. He is wearing a green Gap sweatshirt and sneakers to match. “All right, let’s get some food first,” I say, squeezing his hand.

We walk to Quincy Market, and within 20 minutes, we’re all sitting together on wooden cubes at a table among strangers and tourists for a celebratory meal: Greek salad, clam chowder, chicken lo mein. We ask who wants a bite—Yes, yes, take more. And we smile, at each other, and at our phones for dozens of pictures. There can never be enough.

Afterward, we head toward the actual building, the “hall” where hundreds of naturalization ceremonies have taken place over the years, including that of my parents in the fall of 1982. The location for each year’s ceremony is randomly assigned, my mother explains. Theirs could just as easily have taken place at the Moakley Courthouse, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, or Worcester Art Museum. I imagine my parents on that day, standing—holding hands?—on the creaking wood floor where so many like them had stood before, people for whom American citizenship meant a freedom and protection unlike any other, and possibility, like a lit match to ignite a new life.

Yet I recall a line from one of Annie Dillard’s great essays: “There is another kind of seeing that involves a letting go.” What did my parents let go of that day they lifted their right hands? A past, yes. A country, yes. But also: never again having to worry about not belonging.

We zigzag our way through the crowd, step outside into what is still one of the sunniest October days I can remember, and approach the grand brick building with arched windows, its white steeple making it look even grander. Did it used to be a church? Was the architectural design intentional? Did the building always hold such significance?

“This is it?” my son asks.

From where we stand on the steps of Quincy Market, I can’t help but see the building through his eyes. The structure resembles a child’s drawing, something he might scrawl with crayons. Simple, but significant.

“Sí,” my mom replies, and sneakily hands him some Sour Patch Kids. My children, like me, are inheritors of the sweetness that comes with being a United States citizen, which for us was based simply on the latitude and longitude of our birthplace. Simple, but significant.

On our way home, we decide to drive through Jamaica Plain, the neighborhood where my parents used to live. My mom narrates the past with every street we pass—stories and anecdotes and more than a few murmurings of “Oooh, I remember….” My dad chimes in every so often with: “Take a left.” Soon, names circle back like familiar spices—Francisca, Irma, Esperanza—as well as the mention of real estate prices, and regrets for not having bought a triple-decker as an investment. Back then, though, their eyes were on marriage, having their first child, and, of course, citizenship. After they were sworn in that day in Faneuil Hall, they had filed applications for their parents and siblings, extending the possibility of freedom to other branches of the family tree.

As we reach Sheridan Street, where they had rented a second-floor walk-up, everything is smaller, narrower: roads, driveways, spaces between houses. But in my mom’s memory, it is all massive. She taps the window. “Oh, that hill! I remember in winter. Oh, no … when I was pregnant. Forget it!”

“There,” my father says, when we arrive at the exact house.

The boys tilt their heads up at the second floor, as if a younger version of their grandparents will step out onto the balcony and wave. I look up, too, picturing my parents as a newly married couple, on the verge of a life together.

“This is where you had your wedding reception?” I ask, putting the car in park.

“Forty-eight years ago this October,” my mother says.

While I have seen the triple-decker before, years ago, now I can also imagine my mother standing in the courthouse in Manchester, New Hampshire, on a Monday morning, her hair pressed into thick black waves, maybe playing with her knuckles as she waits for my father to return from a quick drive to the convenience store to buy film. A camera was one of the first things she had bought in the United States. She has no pictures of herself as a child. Not one. Since then, she has made up for the empty photo albums of her past.

When my father finally returned to the courthouse, she was relieved. But then they realized they didn’t have any wedding rings. They had shopped for ones in Downtown Crossing, but two rings cost a thousand dollars. That amount of money could buy land in Guatemala, my father said. So instead they pushed coins into a candy machine in the courthouse lobby and waited for a plastic egg that held rings.

Not too long ago, my mother found a copy of their wedding reception invitation. She used plain card stock, cut into one-by-two-inch rectangles, and typed on each one:

LUIS DE LEON Y DORA FLORES

Tienen el honor de inviter a Ud

y familia a la recepcion, que tendran

con motivo de celebrar su matrimonio

el 25 del corriente mes.

Direccion: 30 Sheridan St. J. Plain

Hora: 7 P.M.

Muchas gracias por su asistencia.

That Saturday evening, they ate tamales and danced in the space made by pushing the couches against the walls. Someone snapped a picture of the two of them sipping champagne with their arms linked inside each other’s.

Maybe this is what it means to move countries, to have one arm always linked to the past, as the other binds to the future. Maybe I am not so different from them. Even though I was born in Boston, I, too, have always felt an in-between-ness, and a deep connection to Guatemala—what the poet Pablo Neruda called “the tiny dark-skinned country at America’s waist.” I know, now, that this connection began from hearing my parents’ stories, these portals to the past. It is why I want my children to hear them. It is, I believe, why my mother and father raised their hands inside the Manchester courthouse and Faneuil Hall so long ago: to embrace the new, but never forget the old. And so, half a century later, on this glorious autumnal day, we all stand together. We angle our heads back, and squint in the sun.