Finding Grace in a Cemetery

I grew up in cemeteries. One Sunday afternoon a month, after Mass, after the midday meal of lasagna or spaghetti and meatballs, my grandmother visited the dead. Mama Rose never learned to drive, so her cousin–Uncle Rum–took her from graveyard to graveyard in his square green Ford. I didn’t have a choice; when Mama Rose […]

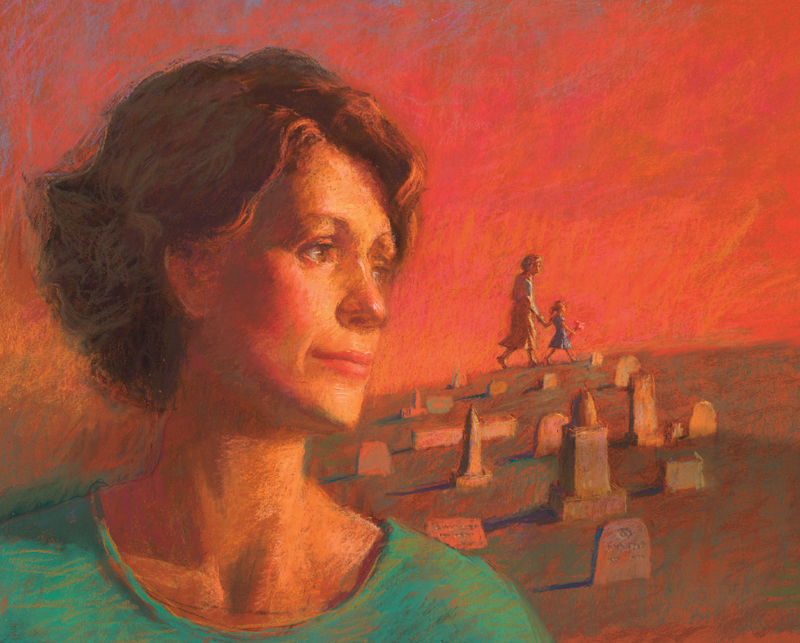

Cemeteries hold not only the dead, but also the living.

Photo Credit : Garns, Allen

Photo Credit : Garns, Allen

I grew up in cemeteries. One Sunday afternoon a month, after Mass, after the midday meal of lasagna or spaghetti and meatballs, my grandmother visited the dead. Mama Rose never learned to drive, so her cousin–Uncle Rum–took her from graveyard to graveyard in his square green Ford. I didn’t have a choice; when Mama Rose ordered us to do something, we did it. My reward for an afternoon tending graves with my grandmother was a sugar cookie from the Rainbow Bakery in Cranston, six or seven miles northeast of our small town of West Warwick, in central Rhode Island.

We went to two cemeteries: an old hilly one behind a church and a more modern one with tombstones laid out in neat, orderly rows. As a child, the drive between the two stretched endlessly, my sugar cookie a far-off treat. But now, knowing that my grandmother didn’t travel far from home (except on her yearly autumn trip to Massachusetts to see the fall foliage along the Mohawk Trail), I imagine they probably only sat at opposite ends of town.

At home, Mama Rose cooked and cleaned with great purpose. Our weekly meals appeared in a familiar pattern of soup on Monday, pasta on Tuesday, a roast–beef or pork–on Wednesday, chops–veal or pork–on Thursday, and something meatless on Friday. Saturday meant boiled frankfurters with beans or homemade pizza and spinach pies. She didn’t appear to take joy in the preparation of our family dinners. Rather, she muttered and moaned as she went through the familiar steps. Hot oil bubbled and splattered in her frying pans, leaving little burn marks up and down her arms. She wore them like merit badges, evidence of how she suffered to feed us. At dinner, she pronounced each roast, each meatball, each bowl of potatoes or green beans, no good. Underdone, overdone, too much salt … none of her labors came out to her satisfaction.

Not so her work on the graves. There, she dug and clipped, watered and deadheaded, until she was satisfied. The graves of her loved ones would be beautiful. Anyone passing any of them would see the care that someone had taken to honor this person, to make this place lovely.

These monthly visits bored me. If Mama Rose forgot about me, I stayed in Uncle Rum’s car with WPRO, the local AM pop radio station, turned on low. I closed my eyes and breathed in the cherry tobacco scent from Uncle Rum’s pipe, humming along with Herman’s Hermits or the Monkees until Mama Rose and Uncle Rum returned.

Usually, though, I was required to tag along behind them. I averted my eyes from the other people in the cemetery, black-clad mourners at newly dug graves; the old ladies fingering rosary beads; the solitary awkward person kneeling stiffly at a stone. Grief and its members made me nervous and afraid. Growing up Italian, I heard my share of stories about witches and ghosts, deathbed dramas, brutal accidents in which cars plunged into icy rivers and children went up in flames. My bedtime stories were filled with images of a young boy buried in his Cub Scout uniform, a baby born with the cord wrapped tightly around her neck. We are all soldiers in grief, my grandmother seemed to want to tell me. But I bowed my head and tried not to breathe the dirt and flower smell of the cemetery.

At her mother’s and her husband’s graves, Mama Rose remained stoic. Just as she approached her cooking, armed with a wooden spoon and a frown, she approached these graves. Uncle Rum toted the plants; Mama Rose marched forward with the spade and the watering can. I lagged behind. When she finished, she stayed on her knees and prayed silently. Then she stood, wiped her hands on her skirt in a kind of That’s that motion, and waved for Uncle Rum to follow her. Sometimes she remembered some distant relative buried nearby, and Uncle Rum carefully drove up and down each path until her memory triggered and she’d yell for him to stop. At those graves, she simply said a prayer and took a survey of how well kept they were, something she reported to us when she got back in the car. It doesn’t look like her daughter comes here at all, she might say, clucking her tongue and shaking her head.

But at the graves of her children, Mama Rose was not methodical or calm. She’d had 10 children–seven girls and three boys–and lost a son and a daughter as adults. I knew the details of their deaths as well as I knew that I would have soup for dinner on Monday and pasta on Tuesday. Her daughter Ann, my namesake, had died at the age of 23, during routine surgery to extract her wisdom teeth. Her son, whom we all called Uncle Brownie but to whom she referred as Tony, had died of a heart attack on Valentine’s Day when I was 3.

I dreaded these visits. Mama Rose pounded the ground and cursed God, raising her fist to the sky as if someone were actually watching. She threw herself onto the graves, tracing their names with her wrinkled hands and sobbing. She dug with a ferocity, jamming the plants into the upturned earth. Dirt filled the creases in her fingers and palms and under her nails. I couldn’t bear to watch.

Eventually she stood and wiped her tear-stained cheeks. Soon I’d be standing in the Rainbow Bakery, waiting for her to select her own dozen pastries–prune Danish and fig squares–so that I could point out the exact cookie I wanted. Back in Uncle Rum’s car, I’d bite into its thick sweetness, feel the grainy sugar on my tongue.

Outside my window, the familiar streets of my childhood passed slowly by. Down Providence Street and the little white school where my brother and I, my mother and her nine siblings, and even Mama Rose herself had gone. Up Prospect Hill, with its dilapidated, rundown houses at the bottom slowly giving way to the houses built by the immigrants, like Mama Rose’s parents. They had stone walls and lush gardens; grapevines, fig trees, tomato plants spiraled upward on high stakes. Women bustled down the street, their kerchiefed heads bent. Men in sleeveless T-shirts chomped on stogies. Children played. This was life. This was home. As soon as Uncle Rum parked the car, I burst from it, crumbs on my jacket and face, as if I could run from what I’d just seen.

There was a cemetery in the woods behind our house. In this small square bordered by a stone wall, the graves were marked with half-buried, jagged, broken stones. The carving was faded. Beer bottles and cigarette butts littered the area. This cemetery didn’t seem like the ones where Mama Rose took me. The people here had died 100 years ago or more. They were strangers, their names exotic: Jeremiah, Prudence, Isaiah, Abigail. Unlike the Debbies and Kathys and Susans who filled my life, these people were from another era, another world.

My brother Skip and I went there to play. On our way, we had to cut through part of a golf course, and Skip often got sidetracked finding stray balls that he could resell to golfers. But I liked to sit in the cemetery and make up stories about its inhabitants. I populated my stories with infant children lost in epidemics, fathers lost at sea, mothers dead in childbirth. These characters loved passionately and died heroically. If I remembered to bring a trash bag, I picked up all the litter and scraped the dirt from the tombstones, tidying. You like it so much here, I’m going to bury you here when you die, Skip would tease me, his pockets bulging with golf balls. No, I’m going to bury you here! I’d yell back.

In 1982, at the age of 30, Skip died in a household accident. Years before, he had converted to Judaism to marry his Jewish girlfriend. In the shock after his death, forced to find a grave for him, my parents settled on a Jewish cemetery nearby with the help of his by then ex-father-in-law. I didn’t think it was suitable for my agnostic brother, but those cemeteries of my youth lay along roads tangled by years and memory. The old one in the woods was probably gone, mowed down by developers who had built new houses in those woods. So on a hot July morning, we buried my brother right off Route 95, across the street from one of our favorite restaurants, Greg’s. Planes were taking off and landing at the airport down Post Road. None of it seemed right–mostly that my vibrant, funny brother was dead. Does your face hurt? he’d ask me when we were kids. Because it’s killing me! Once he had calculated how old we’d each be in the year 2000. You’ll be 49, you’ll be 49, I’d chanted over and over, an unthinkable age. Old.

My mother went to that cemetery daily. After Mama Rose’s death, she had taken over the role of gravekeeper. I was never sure how diligently she tended those graves; I didn’t want or need to know. From time to time she’d mention that she’d been to the cemeteries and that she felt better for having gone. With my brother’s death, she became vigilant in the care of his grave.

That cemetery sits so close to the exit off the highway for so many things we do weekly: discount stores, Greg’s, plane trips. Each time we drive past it, even now, my mother cranes her neck to find Skip’s grave among the countless ones there. As for me, I never went back after the funeral. Perhaps it was all those Sunday trips to cemeteries with Mama Rose that had turned me away from the idea that visiting graves brings us closer to our loved ones. Perhaps it was a cynicism that took root in me after my brother died. I can’t say for sure. But even when my father died in 1997 and we buried him in the veterans’ cemetery, I didn’t visit his grave. Once, on a gray afternoon when my missing him grabbed hold of me and wouldn’t let go, I drove there. I stared at his name on the headstone and tried to feel something: better or different. But I felt only the sadness I’d felt since he’d died.

When the unthinkable happened five years later and my own 5-year-old daughter, Grace, died suddenly from a virulent form of strep, I was thrown into the world of cemeteries and funeral parlors, forced to make decisions while my feet dragged across a kitchen floor still covered in glitter from an art project she’d done less than 48 hours earlier. My husband and I had to choose a casket, a cemetery, a gravesite. Can you do this? I asked him. Not only could he do it, but by doing it he took some form of solace. He could help our child in these final parental decisions. I could not. Looking back, I suppose I could pretend it wasn’t real if I didn’t have to choose the small white coffin, or tour the cemetery in search of the best spot to leave my daughter. My husband’s ability to do these things, and to do them well and with love, remains one of the bravest things I’ve ever witnessed.

Swan Point Cemetery here in Providence is beautiful. That first spring when I moved here from New York City, Lorne and I would stroll its curving paths, beneath pink dogwood blossoms, and read the names on the older stones, choosing which ones we liked for our own, unborn children. A picture of me from that spring sits on a bookshelf in our home: The blossoms are dazzling, and I see in my own eyes the hope and optimism of new love, of a future that seems bright and happy.

Lorne took our children, Sam and Grace, bike riding in Swan Point. He pointed out all the graves of the dignitaries buried there, governors and writers and historic figures. Sometimes they played hide-and-seek among the majestic stones. On another, later, spring day, he drove me down the winding roads, pointing to a spot on a hill, another nestled in trees. Through his tears, he talked about the beauty and virtue of each. Whatever you want, I said, because in that moment there was no perfect spot for Grace except back home with us, where she belonged.

In the months that followed Grace’s death, I heard parents in grief groups talk about the hours they spent at their children’s graves. Many times, the caretaker at Swan Point had to gently tell Lorne to go home. What was wrong with me that I didn’t want to go there? I tried. I’d drive through the East Side of Providence, across the wide and shady Blackstone Boulevard, through the grand entrance to Swan Point Cemetery. I’d park my car and sit on my daughter’s grave and cry, just as I’d been doing back home. Her grave, without a headstone yet, was covered with flowers and seashells, small perfect stones and notes, left by the people who’d loved her. I took comfort in these things, in knowing that she’d been loved and not forgotten.

At Christmas and on her birthday, Lorne and Sam and I visited the grave. We brought flowers and a tiny Christmas tree, and once I left a roll of Smarties, her favorite candy. With each visit, I cried; I hated that I was standing at my little girl’s grave. The injustice of it, the lack of sense to it, the enormity of loss overshadowed everything else when I stood there.

As the years passed, my father-in-law was buried beside Grace, my friend Barbara a few graves away. We came to know the parents of the young woman who had died a day before Grace and was buried right nearby. Each of their graves was marked with a headstone, but this final act for Grace remained undone.

We took a trip to Barre, Vermont, and walked among whimsical, outrageous headstones in a cemetery there. Holding hands, we read aloud funny rhymes and marveled at the boats and motorcycles and sports equipment etched into stones. I was reminded on that trip of the day Lorne and I had spent in a cemetery in France, seeking out the graves of Jim Morrison, Gertrude Stein, and Maria Callas, and of other cemeteries we’d visited, simply to behold the grave of Shelley or Shakespeare. Like the tiny forgotten one from my youth, these cemeteries had seemed removed from grief. But now I imagined the parents or spouses or children who had stood at those graves.

One night, my husband took me to hear a woman speak. She was an artist, a stonecutter who carved incredibly beautiful headstones in an old barn in Foster, Rhode Island. She spoke of how she talked with families to learn about the person who had died. She spoke about etching letters in old-fashioned scripts, and of buying pink and gray stone from Ireland. She spoke with love and pride. I knew she would make Grace’s headstone, and I knew it would be beautiful. But that knowing did not ease my grief.

Over the course of many months, we met with her, bringing pictures of Grace and telling stories, choosing colors and fonts, talking about life and hope. Still, when the headstone was finished, with its elegant curves and writing, with the magnificent figure of a dancing girl and the circle carved from it to allow light to shine through, I could only cry at its beauty, and at its necessity in my family’s life.

Last Christmas, we went to Grace’s grave, just as we do every year. From there, we drive to my mother’s for a lunch of antipasto, Italian wedding soup, and lasagna. Like that sugar cookie waiting for me, the thought of that lunch, served on my mother’s red Christmas plates on a poinsettia-covered tablecloth, gives me strength. Our son, Sam, towering over us now at 6 feet 4, and our daughter, Annabelle, whom we adopted from China four years ago, come with us. Lorne leaves one long-stemmed white rose. The winter sun shines through that careful circle in the headstone. The little girl carved into it dances.

We stand silently, each lost in our memories, our own grief. Back in the car, Lorne begins to slowly pull away. Stop! Annabelle shouts. We have to wait for Grace to get her flower.

It doesn’t work that way, baby, I explain, thinking, wishing, If only it did. In that moment I realize why I don’t go there. No matter how beautiful the stone, no matter how abundant and fragrant the blossoms, I don’t find Grace there.

In grief, we seek that which we can no longer have: our brother, our father, our daughter. Grace is nowhere, and she is everywhere. I find her as I walk along the beach; in the summer rain; in the opening notes of a Beatles song; in Sam’s hugs and Annabelle’s laughter and my husband’s hand in mine. I find her.