Beatrice Trum Hunter | The Natural

More than 50 years ago, Beatrice Trum Hunter published the first natural foods cookbook in America. Now approaching 100, she’s still fighting to help people eat better and live without toxic chemicals.

Beatrice in her kitchen at home in Deering, New Hampshire.

Photo Credit : Gary Samson

Photo Credit : Gary Samson

Photo Credit : Gary Samson

The road in to Beatrice Trum Hunter’s house runs more than half a mile, single lane, straight but hilly, with trees bowing over the road like guardians. It curves past a big beaver pond and ends abruptly at a farmhouse and barn. It’s so quiet. But the door to the farmhouse opens, and a spritely woman descends lightly down the three steps to the grass and walks toward me briskly. Beatrice is a small woman with delicate hands; she’s wearing a dress she made out of Indonesian cotton. She welcomes me as if we are already friends.

Photo Credit : Gary Samson

She leads me inside; her home is modest and utilitarian, but warm, with a pine-paneled kitchen and an eating area near a sunny window. Sunlight comes in through a glassed-in porch running the length of the house. She wants to show me the heart of her house: a pantry as big as a substantial bedroom, lined with shelves, loaded with gallon jars containing edible seeds and nuts, dried fruits and whole grains, much like the aisles of a natural foods store.

It’s October, chilly, and a fire smolders in her rotund woodstove. A large woodbox holds chunks of split wood. “Do you rely on this for heat?” I ask. “Oh, yes,” she says. “I come down in the middle of the night and throw on a chunk.” We settle at her maple drop-leaf table, she at one end, I at the other. I had much to learn about this pioneer of natural foods, this constantly flashing yellow light of caution who has warned us for more than half a century of the dangers that lurk beyond the natural world.

I comment on her New York accent. “That never goes away,” she says. Beatrice grew up in Manhattan, where she met her future husband, John. He was 25 and she was 24. They both worked in public schools, where Beatrice taught visually impaired children. They spent their summers living in Mexico, but felt that they wanted to settle. A teaching colleague had a summer place in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, and suggested that they go there and look around the area. The year was 1948.

“We came up on our Easter vacation. We were driving our old Ford Beach Wagon,” Beatrice says. “Once we crossed into New Hampshire, it was like the air had changed. Finding the house was another matter. We had to walk in with the mud coming over our shoes, city-slicker shoes, you know. Well, I could see how beautiful it would be in the summer. They were asking $2,500 for the whole place, 78 acres with the house, the barn, the cottage, which used to be a blacksmith shop, plus an outhouse. Everything else was in a state of collapse. We said we’d pay cash, and so the agent said, ‘If it’s cash, I’ll let you have it for $1,800.’” The real-estate agent drove through the night to find the former owners in Vermont, who had defaulted. Using a bottle of whiskey for persuasion, he cleared the title.

Beatrice gets up and goes to the back room and returns with a scrapbook containing photos of the house when they first bought it. “It looked like a house that a child would draw,” she says.

They had a well drilled and installedplumbing and electricity; John built an outdoor shower. It took seven years, but the tumbledown place became their paradise. A new world was dawning.

Photo Credit : Gary Samson

John was handsome, and Beatrice was a long-haired beauty, sometimes compared to Nefertiti. “I had hair so long I could sit on it,” she says. She touches her cropped hair, recounting that a reporter once noted that her hair looked as though she’d cut it herself. “My hairdresser was very offended!” she says with a laugh.

And so their lives unfolded in the little town of Deering, population 300 at that time, and 250 long miles from New York City. When they moved permanently to Deering in 1955, John’s mother, the well-known photographer Lotte Jacobi, joined them. A German Jew, she had fled the Nazis in 1935, to New York City, where she opened a photography studio.

“Lotte was like Marie Antoinette in the country,” Beatrice recalls with laughter. “But she did like it. We had a garden, but the way Lotte handled it, John used to joke that each tomato cost us about two dollars.”

They raised the roof in order to put in dormers and built a big porch on the sunny side of the house. “We realized that we could house and feed guests for much-needed income,” Beatrice says. “We put in a pond for swimming and planted pink water lilies.” Outside the kitchen window, I can see the old “swimming pool,” the lilies still in bloom. “It’s like a Monet,” she adds, “gradually taking over the pond.”

The inn had no name. It needed none; it sold itself.The guests, many of whom were naturalists and photographers, loved it, despite its rustic nature and the absence of a phone: “We had a lot of people who wanted to get away from the telephone. We advertised, ‘No entertainment.’”

Photo Credit : Gary Samson

Beatrice prepared three meals a day, using only wholesome natural ingredients. Eggs and homemade muffins and popovers for breakfast, bread and soup for lunch: “We called it soup du jour because it was often made of something from the day before. Meat or fish for supper, vegetables fresh from the garden, fruit and cookies for dessert. I often made cheese-and-onion pie; everybody loved that.” She had a stone grinding machine and made bread from whole grains. Some people stayed all summer.

She cooked and she cleaned and she plumped pillows in the summer. Fall was for lectures, the winter for writing. She never had a best-seller, but her message was persistent: Toxic chemicals hurt both people and the environment. “We ran the guest house for 17 years, and finally I said to John, ‘I can’t continue,’” Beatrice explains. “By that time I was busy with lectures and teaching, book tours, always moving around. I had no time for myself or the guest season.”

Eventually, there came a divide. In their remote paradise, Beatrice and Lotte were laboring in their personal trenches, but John couldn’t settle. “He went from one thing to another,” Beatrice explains. “He never seemed to know what he wanted, but I did.”

In 1980, Beatrice and John divorced. She was 61 years old, and this was her great liberation: “John moved into town, and I stayed here. Whenever he came to see me, I’d stand in the doorway and cry out, ‘Free, free, I’m free at last!’ When I told Lotte that we were separating, she looked at me and said, ‘What took you so long?’”

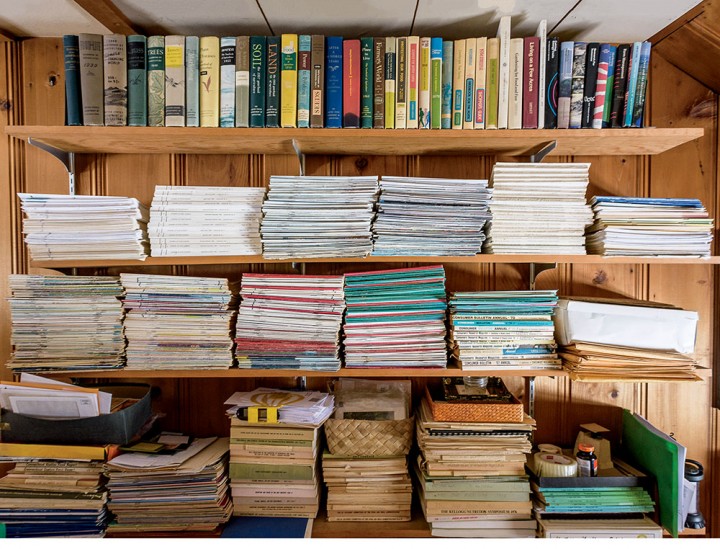

Beatrice is like a jack-in-the-box, getting up and down, going upstairs to retrieve things to show me, and going out onto the porch, which houses the archives that she hasn’t yet donated to Boston University or the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard. In winter she also uses this porch as her gym, walking the 40-foot length of it over and over, putting a yogurt lid down on the floor to retrieve at both ends.

But mostly, Beatrice is a writer, the the topics of nutrition and toxins being of great interest to her. She could hardly have foreseen it, but her early years steered her into this lifelong mission.When she was still in high school, “I began to realize that I was tired, my skin wasn’t good, my hair seemed straggly,” she says. She came across a muckraking book, 100,000,000 Guinea Pigs by Arthur Kallett and Frederick J. Schlink (published in 1933), that proclaimed that the American population was being used as guinea pigs in a massive experiment undertaken by manufacturers of foods and pharmaceuticals. The book became a best-seller. For Beatrice it was the point of no return: “It was a mind-blowing book. It showed how unprotected America was.” She rearranged her life in response.

“The first thing I did was to cut out sugar,” she explains, “and then I began to use more whole grains and more fresh vegetables and fruits. I had rickets as a child. I was brought up on a terrible diet.” Soon, Mr. Schlink, as she still refers to him, became her mentor. He published Consumer’s Research, and he asked her to write for him: “Ultimately I became food editor of Consumer’s Research. I was their food editor for over 20 years, until finally, after more than 75 years, the organization came to an end. They had depended solely on subscriber money.”

Though her books sound scientific, Beatrice is neither scientist nor nutritionist. But she holds degrees from Brooklyn College (B.A.), Columbia University (M.A.), Harvard, and New York University, and is a meticulous researcher and comprehensive writer. What she writes, she intends to be understood by average people: “I’m self-taught. I’ve never hesitated to ask for help from reliable sources when I’ve needed it. What to call me? Call me a concerned consumer.”

Beatrice gets up again. “Maybe you’d like something to eat or drink?” She goes into the kitchen, and I follow her to offer help. “No, no,” she says, “I never accept help in the kitchen.” Her kitchen today is the same one that was so busy feeding all those summer guests: a long counter, worn through time, and where once was a flat-basined iron sink with hand pump, now sit a modern electric stove and a small dishwasher. John built the island counter for kneading bread. Everything is made of pine, handcrafted by John and soft from time and constant use. “We wanted it to be low-maintenance and natural,” she explains.

While we talk, she brews a pot of tea, fills a small bowl with whole raw almonds, cores and slices a cherry-red Baldwin apple, and places the slices on a pretty plate. This is her idea of fast food—meals that are simple, just what she can handle at this age, but always nutritious.

It was in this same kitchen that Adelle Davis, who was, at that time, America’s premier health-food writer and the author of a series of cookbooks that began with Let’s Eat Right to Keep Fit, came to call, sometime in the late 1960s. She arrived unannounced, as Beatrice and John had no telephone. When Adelle arrived, Beatrice was making yogurt, which was a somewhat esoteric substance in America at the time. “Adelle was very interested, because she was a great fan of yogurt,” Beatrice recalls. “She wanted to learn my technique.”

Adelle had heard Beatrice speak at a forum in Peterborough, New Hampshire, on the deceptive practices that the food industry was using in packaging. “She came up to me after the talk, and she said, in her gravelly, beer-barrel voice, ‘You’re a gal out of my own heart.’” They became friends; Beatrice later wrote a chapter on meat for Davis’s Let’s Eat Right book and edited some of her manuscripts, without remuneration. “I considered it an honor,” she says now. “Later Adelle went through a lot of personal crises and became quite a drinker and a smoker. But I still consider her a pioneer in the field.”

Another like-minded union came when Beatrice met Paul and Betty Keene, the founders of Walnut Acres in Penns Creek, Pennsylvania, whose products were among the first commercially available organically raised foods in America. Beatrice corresponded with the Keenes, sharing ideas and innovations. It’s important to remember what most Americans valued in the 1950s: DDT, which had been used during World War II to control the insect carriers of malaria and typhus, was promoted now as a pesticide for all those new lawns and for farms as well. Processed foods were overtaking fresh foods from the farm faster than crabgrass. Organic farming was considered un-American, maybe even Communist.

In that climate, Rachel Carson also came knocking on Beatrice’s door, also unannounced, in the late 1950s, before the publication of Silent Spring. “I was very much involved with the pesticide problem at the time,” Beatrice explains, “and when I was speaking before garden clubs, I found that they really didn’t want to hear about pesticides—they wanted to know what to do instead. So I began gathering information for a book I called Gardening Without Poisons.

I was also writing letters to the editor of the Boston Herald on the problem with pesticides.” A friend of Carson’s clipped the letters and sent them to her at her home in Silver Spring, Maryland. Soon after, Rachel Carson and Beatrice, two diminutive Atlases against these giant corporations, became correspondents.

Rachel Carson wrote to Beatrice in January 1958: “She said that she found my material very interesting. And then she wrote, ‘I’m sure I could find the documentation of what you have been writing but it would be much easier and quicker if you could supply them to me.’” Beatrice sat down and the next day sent back an eight-page, typewritten, single-spaced letter to Rachel Carson, listing 75 sources on the dangers of DDT and chlordane—a Google listing before there was Google.

“Carson was struggling with cancer at the time,” Beatrice recalls, “but she didn’t want that known publicly, so she got a wig, and then her book came out in 1962. She was interviewed on CBS; I still remember the reporter. He starts off with something like ‘Are you the little woman who has created all this fury?’ You know, condescending. Later they wanted to present both sides, since many of their sponsors were chemical companies. So they brought in the head of research at American Cyanimide. He looked fierce, like the Grand Inquisitor sitting opposite this very pleasant, gentle-looking lady in the wig. He was nasty and aggressive, and she simply sat there, very calmly, giving the facts. In the end, she won hands-down because he became the ‘hysterical woman’ and she was the voice of reason.”

Rachel Carson died in 1964 at the age of 60. Adelle Davis died 10 years later at the age of 70. Beatrice is still here to process this time of turmoil in American life, when a curtain opened and people realized that toxic chemicals were taking a toll on people and nature. “Our consciousness was raised,” Beatrice concludes.

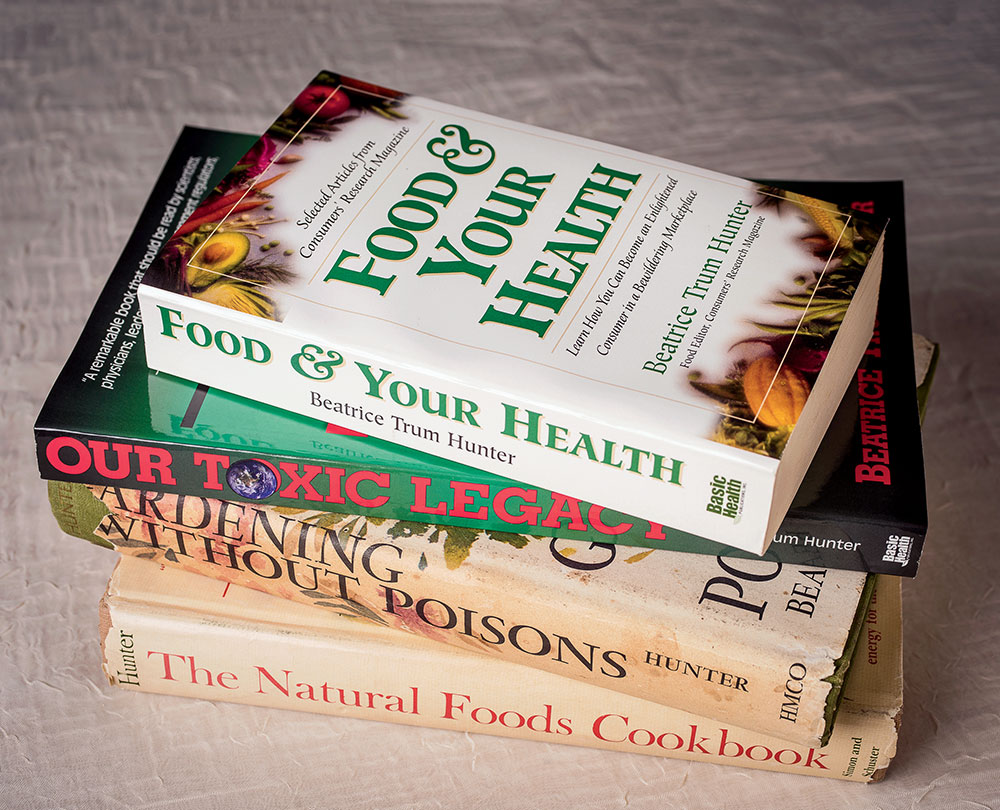

Beatrice Trum Hunter’s The Natural Foods Cookbook was published by Simon & Schuster in 1961, the very first natural foods cookbook published in this country. She based a lot of it on her cooking for those summer guests. In 1964, Houghton Mifflin reissued Gardening Without Poisons, which had first been published in 1961 by a group of gardening enthusiasts. “I’ve always felt that I’ve been before the wave,” she says now, sitting in her spartan home. “I never thought I’d live to see supermarkets with whole foods. I’m amazed at the number of people who have written to me to tell me how I’ve changed their lives.

“So in that way, it’s great, but in the other way, the industrialized approach to agriculture, monoculture, GMOs [genetically modified organisms], and the use of antibiotics with farm animals, these are all much bigger than before and very formidable.”

Beatrice is only ahead of the wave in her thinking and in her writing. Otherwise, she is considerably backward: She owns neither a computer nor a cell phone nor any other “newfangled” devices. She finally had a hand-me-down phone installed in the 1980s; it’s concealed inside a cabinet at the bottom of her stairs. She relies on handwritten correspondence to keep up with her friends, who live far and wide. “People call me a Luddite,” she notes, “but that makes me feel proud.”

In 2008, Beatrice resided for several months in an assisted-living facility. “I was sick and didn’t think I was going to make it,” she explains. Having learned a lesson from Lotte, who never threw anything away and left Beatrice to deal with all her weighty possessions, she got rid of most of what she owned, including her books and cameras: “I gave them all away. Fortunately, I didn’t sell my house.” She recovered and returned to her home.

Beatrice’s voluminous correspondence, including that with Adelle Davis and Rachel Carson, is contained in 43 cartons on file at the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center in the Mugar Memorial Library at Boston University. When I went to explore some of those letters, the groaning cardboard boxes were wheeled in to me on steel carts. Each year, Beatrice continues to add boxes to the collection. All her books, many now hard to find, are in the collection at Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America.

Beatrice is an inveterate recycler and proud of it. “My friends call me the Great Recycler,” she says. Anyone who receives a letter from her will find it inside an envelope saved from other correspondence, cleverly turned inside out to be used anew. Often, her letters are written on the backs of requests for donations or subscription renewals. When others complain about junk mail, she delights in the opportunity it presents. She uses the insides of billing envelopes to make origami birds; the pages of old magazines become small boxes, a skill she learned in kindergarten. She gathers flower petals and leaves from her land and presses them into botanicals—beautiful portraits of her woods, which she gives to friends. She keeps Lotte’s archives at the Dimond Library at the University of New Hampshire, organizingand sorting whenever a friend can drive her there. “There’s always plenty to do,” she says.

Seven years ago, she turned in the keys to the last in a long line of Volkswagens. She can recite all the colors and models, beginning with a dark-green microbus and ending with a red semi-automatic Super Beetle. “The last one actually had a heater that worked,” she boasts. “I used it until prudence told me it was time to stop driving.” She exists in her secluded place in the forest with the help of friends and neighbors who visit and take her shopping.But there are long stretches of time when she’s alone. “Being here, I’m never bored; I feel totally comfortable,” she says. “I hear people talking about cabin fever; I can’t understand it. I’m not a hermit, but there are great pleasures in solitude.”

Everyone wants to know Beatrice Trum Hunter’s secret to a long life. She doesn’t find it remarkable: “It’s not genes. My mother lived to be 80, and my father died in his 70s. Keeping busy is important, and it doesn’t always have to be serious. A sense of humor helps, as does being adaptable.”

Beatrice has three nephews she’s very fond of, but no other family. In many ways, her friends are her family: “I always felt that I was dropped by gypsies into a family with whom I had nothing in common. We all find our families after a while, and I’ve found a number of wonderful mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters!”

While excluding sugar and processed foods from her diet has perhaps helped extend Beatrice’s life, what sustains her is her writing: “I never could separate work from play, and to me, writing is like breathing. Writing is a lonely occupation, and I think being alone is wonderful in terms of having quiet. Even if the telephone rings, to me it’s like a great big crystal chandelier being shattered. And time goes by so rapidly when I’m writing. I look at my watch and I can’t believe it, how the time goes by.”

A small plane drifts overhead. Crickets chafe in the late-afternoon sun. Beatrice is out on the porch again, this time looking for an article she wrote in 2012 for Price–Pottenger’s Journal of Health and Healing on the dangers of antibacterial soap, which has only recently come under attack. Once again, ahead of the wave.

Beatrice sees her time in assisted living as a rehearsal for the inevitable. What’s odd is that she sees the passage of time in reverse, now that she’s back home: “I found that when I was there, I thought about everything in short little boxes. But now that I’m home, I find I can think in a broader way, much further into the future.”

Beatrice is a woman of great humor who loves nothing more than a good laugh. Despite her mirthful outlook, she maintains the hope that the deadly serious messages that she’s been putting out there all these years can still take hold. A woman who hasn’t eaten sugar or processed foods since her earliest years, a woman who has retained vigor and beauty and who takes pride in rejecting the new world—you might say she’s the living example of how to live well and long. Naturally.

Note:We are saddened to report that Beatrice Trum Hunter passed away May 17, 2017 in Hillsborough, New Hampshire. She was 98.