Tropical Storm Irene Will Never Be Forgotten

Five years after the devastation of 2011’s Tropical Storm Irene, those who lived through it in Wilmington, Vermont, remember both what they lost and what they found.

Downtown Wilmington at the height of Irene’s flooding on August 28, 2011. This photograph was taken by local resident Eric Craven, who awoke that morning to find his own apartment filling with water. “My girlfriend and I hastily evacuated and went to my parents’ house,” Craven says. “From there we journeyed downtown, where we witnessed the town being flooded from start to finish.”

Photo Credit : Eric CravenIt had already been an unusually stormy season when Hurricane Irene first made American landfall in North Carolina on August 27, 2011.

What had begun as a tropical wave off the west coast of Africa two weeks before now closed in on America’s Eastern Seaboard with winds reaching 85 miles per hour and torrential rains that would dump as much as 11 inches of water on parts of the Northeast. Eventually downgraded to a tropical storm, Irene was no less destructive. Racking up $15.8 billion worth of damage, Irene’s landing, just weeks shy of the 73rd anniversary of another horrific weather event, came to rival anything that the Hurricane of 1938 had wrought.

In Vermont, Irene was especially catastrophic: six deaths, more than 500 miles of roads damaged or destroyed, many towns made inaccessible for days. Covered bridges in Bartonsville, Quechee, Taftsville, and Northfield Falls were either wiped out or battered to the point of ruin; Brandon’s House of Pizza floated into the middle of U.S. Route 7; in Jamaica four homes were swept out into what one resident described as “liquid earth.” Farther north, the Rochester cemetery was washed out, scattering bones and coffins across town. “It was a horror movie,” one Vermonter recalled. “One I hope I never live through again.”

Perhaps no Vermont town felt the storm quite like Wilmington. Built on the banks of the Deerfield River, this southern Vermont community of nearly 2,000 residents was transformed into an unrecognizable scene of flooding and destruction that Sunday morning of August 28th. Main Street became a tumbling waterway of building sections, propane tanks, farm animals, and waste. When the river finally retreated, it left behind a thick glaze of mud and a downtown of overturned lives. The flood also swept away a young woman who drowned trying to escape a car that had been trapped by floodwaters on Route 100.

The cleanup and recovery from Irene took years. For some, it continues even to this day. To mark the five-year anniversary of the storm, we asked a number of Wilmington residents who lived through it to tell their stories.

‘We’re going to have a problem’

Flooding wasn’t a new phenomenon for the community. A 1927 hurricane had taken out the Main Street Bridge, and the ’38 storm had nearly done the same. In 1976 Hurricane Belle poured more than three feet of water into some downtown businesses. In other years, the Deerfield had spilled into parking lots and buildings. At Dot’s Restaurant it wasn’t unusual for John and Patty Reagan to clear out their basement when a big rain came. “It’s just a part of life here,” one resident says. Still, the preparation for Irene was uneven. Some braced for calamity, others less so.

Susan Haughwout Wilmington Town Clerk

That week I ran into a woman at one of the bars downtown having a cocktail after work, and she remarked about the birds—how they were acting unusual and she felt that something was going to happen. Well, nobody paid attention to her; people thought she was being silly. But she was right.

Photo Credit : Jonathan Gitelson

Patty Reagan Owns Dot’s Restaurant with her husband, John

Even during normal rainstorms we’d get a call from the fire department in the middle of the night to tell us that the river was going to come up. But this time they called us three days before and said, “This is going to be a good one.”

Photo Credit : Jonathan Gitelson

Dana Stone Former Housecleaning Supervisorat Mount Snow Resort

I didn’t really think it was going to flood like it did. Nobody really did. On the morning of the storm, though, the mountain told us that if we wanted to go home we were free to do so. A lot of them decided they wanted to stay there.

Photo Credit : Jonathan Gitelson

Ken March Wilmington Fire Chief

That whole I week I stayed on top of the storm, tracking it and reading as much about it as I could. What I saw was that it was looking to be very similar to what happened in 1938. I saw the highs and lows, where everything was going, and I thought, We’re going to have a problem. We started making preparations the day before, but a lot of people thought I was just crying wolf. You know: It’s not going to hit us. I said, “No, you don’t understand, it’s going to.”

Photo Credit : Jonathan Gitelson

Lisa Sullivan Owns the downtown bookstore, Bartleby’s Books

We were visiting my family in Rhode Island. My husband, Phil, is a weather junkie and had been watching the patterns and getting concerned about how much rain we’d already had and how wet the ground was. That Saturday he said, “We have to get back. I think there’s going to be water in the store.” My father thought we were crazy: “We’re going to have a hurricane party! We’re in Rhode Island—we’re the ones who are going to get the storm!” He was annoyed that we left.

Photo Credit : Jonathan Gitelson

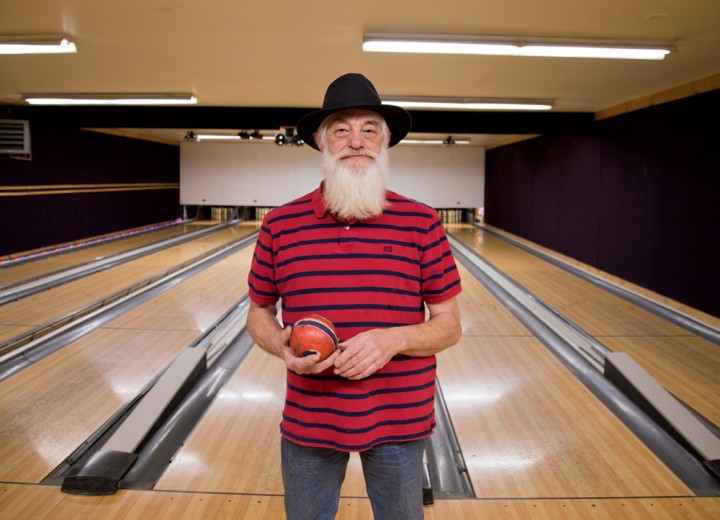

Steve Butler Owns North Star Bowling

We were told to brace for high winds, so the day before the storm I went out and moved anything that might be blown away. I also had a large bundle of clapboards that I threw a tarp over and tied down tight with rope. There was no way they were going to blow away. Well, that pile ended up floating around in the parking lot.

Photo Credit : Jonathan Gitelson

Florence Crafts Lives two miles north of downtown; her husband and sons established a local logging business

My late husband, George, had grown up on this property and was 5 years old when ’38 hit. He watched his house get ruined pretty bad. I’ve lived here since ’56, and we’ve had water in the cellar before, but you could clean it up right away. When I heard the weather report for this storm, it sounded like it was just going to stay west. [The report] never said anything about its coming to Wilmington until later. But just to be safe, I moved a few things, some pictures and a few other family mementos, to the top of my refrigerator.

Five days before Irene struck, the Weather Service issued warnings about potential flooding, and Vermont governor Peter Shumlin declared a state of emergency long before a trace of storm clouds appeared over the state. For those living outside town, it wasn’t even immediately apparent that Irene was more than just a severe rainstorm. But as the rains continued, reports about what was happening downtown began to trickle in, and Irene’s breadth came into focus.

Camille Swanson Nurse at Family Medical Center

Around 9:00 or so my husband, Doug, had tried getting into town and couldn’t. It was already flooded. He came back and said, “Come with me, because you just won’t believe what’s happening.” We went over to a place by Stowe Hill, where it was high enough so you could see the flooding. You just couldn’t believe it. We watched the water just submerge the bowling alley.

Florence Crafts It was a common thing that whenever we thought the river was going to get high, we’d take our cars up to the school. So that’s what we did. But then it came really fast. My son had come over, and he got the truck started. We wanted to get as much firewood as we could loaded into the truck, but we never had the chance. We had to leave.

Steve Butler I remember looking out the window and laughing because there wasn’t even a puddle in the parking lot, not even in the lower-back section that’s always the first to pool up. I thought we’d dodged a bullet. So I took a shower and then headed outside. It was around 9:45. The lot was still dry. I walked 60 feet, and in those 15 seconds the lot filled up with three inches of water. It was so fast I thought a water main had broken. I didn’t think for a second it was a flood. Twenty-five minutes later the water was more than five feet high. My partner, Bev, and I had two dogs in the trailer where we lived behind the bowling alley. I went for the dogs, and we got them loaded into my truck.

At this point there was water filling the truck. When I opened the door, it just gushed out. But I got it started and drove to a nearby spot that’s higher ground.Then we all made it back to the North Star—Bev is short and was on her tiptoes—where I had an apartment rented out on the second level. I knocked on my tenant’s door and said, “Sorry, but we’re going to have to invade your space for a little bit.” That’s where I watched the rest of the storm.

Hannah Swanson Was a sophomore at Twin Valley High School in Wilmington; now a junior at Binghamton University in New York

That river is far away, but water had filled up the field and crossed Route 100. Everything was just water. You could see it rising. Watching the bowling alley and seeing the deck get submerged, all the chairs and tables just floating around, it was crazy. I kept thinking about how we used to have dinner there all the time, and then suddenly there was nothing there.

‘oh my god! oh my god!’

For years residents had looked in awe at the high-water mark on the police station that showed where the Deerfield River had risen during the ’38 hurricane, 65 inches above the sidewalk. At the height of Irene, however, the Deerfield managed to surpass that historic mark. The storm’s onslaught had come fast. The rain had started the night before. By 6:00 a.m., when fire chief Ken March arrived at the station, it was coming down at a steady pace.

Not long after, early breakfast customers filed into Dot’s at 7:00 and looked out at the rising but still contained river. Uncertainty filled the place as diners wondered what exactly Irene would bring. By 10:00 water was pouring over the railings of the Main Street Bridge, bringing with it a fast current of propane tanks, dumpsters, and appliances. “It sounded like an angry freight train,” recalls March, who had begun receiving reports about a possible drowning a few miles north.

Even those who had been prepared for flooding were caught off guard by Irene’s voracity. In one dramatic event, firemen bailed out of the station windows to evacuate the building.

Joe Szarejko Wilmington Police Chief

I got to the firehouse that morning around 6:00 to watch the Weather Channel with Chief March. I checked the river height before going in; it was already rising at that point. Around 15 minutes later I went back out to check it, and the water had risen three feet in just that time. That’s when I knew we were in trouble, ’cause I’d never seen it come up that fast before.

Susan Haughwout

That night before the storm I couldn’t sleep. I was nervous. I tried to doze, but I had the Weather Channel on the whole time. I was pretty panicked. Finally at around 5:00 I got out of bed. I told my husband, “I have to go down to the office and start moving books so they won’t be damaged by flood-waters.” I stopped in at the fire department. I spoke to one of the men: “Do you think I ought to prepare for something worse than the ’38 flooding?” He looked at me and said, “Yes.”

Patty Reagan

We opened the restaurant at around 7:00 that morning, and people started showing up. One of them was Susan Haughwout. It was raining, and we were talking about the storm, but we had no idea it was going to be what it became. But as Susan was getting ready to leave—I’ll never forget this—she turned and looked at us and said, “I’m sorry for your loss.” I was like, “What? Shut up! What do you mean ‘our loss’?” We were still high and dry at this point. But we soon sent everybody home. Then we just started pulling pictures off the wall—the stuff we’d never be able to replace.

Monique Johnson Lives just north of town; her husband, Brian, is with the fire department

Brian got a call to come down to the station around 6:00. I didn’t realize how high the water was getting, because even though we live above the river, you can’t actually see it because of the trees. At around 7:00 he called me and said that the high school had been opened up as an emergency shelter, and [asked me if I could] go down there to help out. I still didn’t get it. I said, “Sure, let me just get some things together and take a shower.” And he cut me off: “No. Nobody’s taking any showers. You need to get down there.” So I started getting things together, like snacks and dry clothes for the guys at the department. An hour went by and I still hadn’t left. My husband called again: “Where are you?” When I started explaining, he said, “I don’t need dry clothes! I just need you to get to the high school right now.”

Lisa Sullivan

We’d gone to Dot’s to get something to eat, and my husband, Phil, saw the water starting to come over the bridge: “We’ve got to go to the store.” So for the next 45 minutes we were moving books from the bottom two feet onto tables and chairs, because we thought maybe a little water gets in here and that’s it.

But the water kept getting closer. It was rushing around the store, and Phil said, “I’m worried about the building. We need to open the doors to relieve the pressure.” As soon as we did, one of those large whiskey barrels that we’d put flowers in came rushing into the store. The water was knee-deep.

There was an intense propane smell in the air, because all these tanks were getting pulled off buildings and floating down the street. We were scared something might blow. We ran up the hill behind the store to a spot on Rayhill Road where a bunch of people, including the Reagans, had gathered to watch what was happening to the town.

Monique Johnson

As I was backing out of my garage to go to the high school, my neighbor drove by in a pickup and asked where I was going. When I told him, he shook his head: “Not in the car you’re not.” I climbed into his truck, and he brought me to the high school. It’s only a mile-and-a-half ride, but the only thing I could say as I saw that water and devastation was “Oh my God! Oh my God!”

Ken March

Just before we evacuated the station, I looked out the window and saw the roof of the baseball dugout from the high-school field float right by. It wasn’t long after that I made the call to leave our station. Incident command became my pickup truck, with two radios and a cell phone.

Bert Wurzberger Was weeks away from opening a downtown aquarium store; his parents, Sue and Al Wurzberger, own the nearby 1836 Country Store and Norton House Quilting

I got into the shop around 7:30 that morning. The night before, I’d moved stuff to the second floor just in case.The river wasn’t that high. Within an hour it was waist-deep in the parking lot, and I was scrambling to get the last few things I could to the upstairs. Then I ran up to the Country Store to call my parents. I’ve seen a lot of floods, and I could tell this one was going to be the worst we’d ever experienced. “This is going to be bad,” I said. “Worse than ’76. What do you want me to do?” “Turn off the electricity to the buildings and leave,” they said.

Susan Haughwout

Based on how high the water had been in ’38 and how high our building sits, I figured I needed to move anything in our vault that was shelved below my waist. I wasn’t sure we’d be able to move everything, so I had to calculate which materials were higher priority. The big land-record volumes—they weigh probably 20 pounds apiece and there are 300 of them—contained deeds, mortgages, and liens. Those were first. Then there were documents like old town-meeting records that might be a historical loss, but they weren’t accessed often.

I had a small team of helpers: Ann Manwaring, our state rep; Pat Johnson, the assistant town clerk; and her boyfriend, Larry Nutting. We stacked the land volumes onto office chairs, then wheeled them into the elevator to take to the second floor. It was relentless. I don’t know how many chairs we rolled up and down the building. At one point we couldn’t move the filing cabinets, so Larry, who’s really strong, just started ripping the drawers right out. They were absolutely full. I still don’t know how he did it.

Bert Wurzberger

I just started running up and down Main Street trying to warn people about what was about to happen. I felt like Paul Revere. By this point my building had already come off its foundation. There was this loud crunch, and then it just popped up like a cork.I made my way to the hotel, The Vermont House, which is where I saw Ann Coleman’s gallery building just pop up, slab and all, and float away. It all happened so slowly that I felt like I could have just grabbed it. That was my urge, to pull it back into place.

Ken March

After we’d closed the bridge, one of the selectmen wanted to cross it to get back to his house. I told him I couldn’t allow him. “I’m going,” he said. “No, you’re not,” I said. “Yes, I am,” he said. Now, he’s a bodybuilder, but I had to hold my ground. He said, “What about my cats?” I looked at him and told him, “They’ll take care of themselves. They know how to do that.” He finally turned around and left. He apologized later.

Mark Denault Detective Sergeant with the Wilmington Police Department

Some people underestimated the gravity of the situation. People wouldn’t leave a building when you told them to; then they’d be stranded on a roof. Others drove into the town center, right into the raging water. We had to rescue one lady, whose car had stopped in the water, with a backhoe. She climbed right from her car into the bucket. Another time we had a guy kayak right down Main Street. It was a raging river at that point, but for some reason he thought it would be fun.

Ken March

Emotions were high. The adrenaline had kicked in. The guy who decided to kayak had been under water and by chance had popped back up. Happenstance was the only reason he was alive, ’cause by every right he should have been down in the reservoir with the rest of the debris. The police were hollering at him, and he was flipping out, and then I finally stepped in and said, “Listen to this radio! You’re hearing about a young lady who’s dead and you’re doing this crap!” It finally hit him, and he just started crying.

Susan Haughwout

As we worked, I’d go outside to check the river. A couple of times I came back inside and told the group, “It’s getting really bad. We better go.” And they just said, “No, we’re not done yet.” At one point I went out and saw that the water had breached the bridge and all this stuff was pouring over it—dumpsters, propane tanks, logs—just flying past.

Finally at around 10:30 I saw that the water was coming up to the sidewalk and told the group that we needed to leave and get to safety. Ann had borrowed my car to get a camera so we could document things, and when we stepped back outside, she couldn’t find my keys. We took a quick look through the office, but it was hopeless. The car was parked in front of the building, right in the path of the water. Poor Ann was so upset, because we both knew it wouldn’t survive, but I didn’t care. I told her, “It’s a car, it’s not a big deal.”

Bert Wurzberger

The water was probably five feet high on Main Street. There was this telephone pole that had started to come down, and right next to it was this giant propane tank. I saw a bunch of people standing in the water on the lawn of the Wilmington Inn. I yelled, “You need to run.” Everybody got out of there except for this 10-year-old kid who just stood there. I don’t know if he froze or what. So I grabbed him and pulled him onto the porch, and at that very second the pole crashed into the water, and there was this huge explosion. It made this incredible Bang!

Patty Reagan

We couldn’t see the part of the building that was the kitchen, which was cantilevered over the river. But seeing everything else happening, I figured it had been sheared off. It was old construction, and I couldn’t imagine it had survived. Later, I couldn’t believe it had hung on. The old girl was tougher than I thought.

‘In an instant she was gone’

Nine miles north, at Mount Snow Resort, the rains made Ivana Taseva, a 20-year-old summer employee from Macedonia, nervous. Taseva had come to Vermont two months before with her boyfriend, Kiril Donev, to work in the housekeeping department. She was pretty, with an infectious smile, and just a week away from her 21st birthday. At around 10:00 in the morning, as Irene pounded the resort grounds, Taseva pleaded with her boss, Dana Stone, to drive her to her apartment in Wilmington. Stone tried to talk her out of it, but then reluctantly agreed.

Dana Stone

I didn’t think going into town was a good idea and told her that the mountain was offering condos for people to wait out the storm. But she insisted on going home. So I agreed to take her and her boyfriend, Kiril. I remember there was a little gully as you left the resort, and it was filled with probably a foot of water, and we blew through it. Ivana just laughed. She loved it. “Let’s do it again,” she said. So I backed up and we went through it one more time and then headed toward town.

The closer we got to downtown, the worse the conditions became. About 15 minutes into it, we knew it was serious, and I kept saying, “We should turn around,” but she just didn’t want to. Maybe she thought she’d feel safer in her own apartment. But then, maybe eight miles in, we reached a point where we couldn’t turn around. I was driving a Ford Explorer, which sits up pretty high, and at one point the water was blowing up over the front end of my car. But I knew we were close to the elementary school, which sits on a hill, so I figured if I could just get there, we’d be all set.

When we first got into the deep water, my car stalled. I was able to get it going, but then it stalled again, and this time it wouldn’t restart. The water was so deep and moving so fast that it just kind of picked us up and we floated, and eventually we ran into another vehicle near the school that was tipped on its side. That stopped us from going any farther.

We were all panicked, but Ivana, who was sitting in the back, was really scared. She kept asking, “What are we going to do?” Kiril said he would get out first. We couldn’t open the doors, so I kept the power on, and we opened the windows and crawled out that way. After Kiril got out, I climbed out the passenger side. By the time I got out, Ivana wasn’t there. I don’t know if she slipped, or panicked, but I mean in an instant she was gone.

The water was up to our knees and rushing past us so fast. We kept hollering her name, but there was no sight of her. Kiril was yelling and crying. We then headed up to the school, and it was there that Kiril told me that she didn’t know how to swim. I didn’t know. If I’d known, I’d have gotten out with him and then we both could have helped her. But I didn’t know until after.

When we got to the school, we told them what happened. They gave us some blankets to warm up, and then we went out and looked some more. But there was no way we could go out into the water again—it was moving too fast. I saw buildings floating down, propane tanks—it was like some kind of horror movie. And we couldn’t get any police or ambulance out to us. Nobody could reach us.Eventually we were taken by ambulance to the emergency shelter at the high school. It had taken a couple of hours for them to arrive. You wanted to believe that she’d made it, but all that water, the fact that she couldn’t swim, it just didn’t seem likely.

She was so young. She had her whole life ahead of her. I’d rather it had been meinstead of her. I still blame myself for it, ’cause I was the one who drove them. I mean, if I’d just said, “No, we’re not going,” everything would have still been the same. She’d still be alive.

‘I cried like hell, ’cause I’d lost everything that I’d worked for’

Nearly as quickly as the waters had submerged Wilmington, they receded. By 6:00 that night, the Deerfield was nearly back to its normal level. But in its wake it had left a downtown that was both devastated and surreal.

Buildings had been blown open by the strong waters, a few even lifted off their foundations and taken downriver. Dot’s kitchen clung to life over the now-placid but still-brown river; trees and bushes were strewn with colorful yarns from a local shop. Logs, fuel tanks, and other debris were piled up at the bridge. Hanging over everything was the thick stench of propane fumes.

For a town still reeling from the Great Recession, Irene’s arrival just weeks from the start of the crucial foliage season was a hardship that for some business owners was too much to bear.

Patty Reagan

Our first look inside the restaurant was around 6:00 that night. The building was undermined all the way around, but we were able to look in through the windows. It was funny, because the tables were all still set. They’d just floated right to the front of the building. I’ll never forget that.

Al Wurzberger

The next morning I got up early and drove downtown. I opened the door to my store, and water just poured out with all this stuff—T-shirts, sweatshirts, candy. I just stood there and cried like hell, ’cause I’d lost everything that I’d worked for. Almost 50 years. That was my barn. That’s what I’d wanted ever since I was 7 years old, and it seemed like it was gone forever.

Steve Butler

Nothing was where it was supposed to be. Two of the lanes pushed up like a tepee that was probably two feet high. By the time we got to the freezers, all the food was spoiled. I ended up hauling 17 dumpsters of trash out of here. That alone cost me more than $10,000.

Florence Crafts

After the rain, the sun came out with a rainbow, so I walked down to my house. The refrigerator had flipped over; so had the big gun cabinet, which had pictures and souvenirs. In the basement there was two feet of mud. The year before, my grandsons had put on a new roof for me, because the old one had been leaking. I’d been worried about the water coming in from above, and instead it came in from the bottom.

Al Wurzberger

Two days after the storm, there were already volunteers here. One fella yelled at me, “Hey you! Come on over here. There’s a crowbar—start tearing this wall off!” Okay. And then somebody else said, “Well, you own it, right?” Yeah. “Okay, we need crowbars; we need hammers.” As days passed, we needed insulation; we needed wood. And I’d go up to W&W Building Supply, and I’d throw the stuff into my truck. We broke screw guns; we had to buy new screw guns. We wore them out.

I ordered wood from a place in Greenfield, Massachusetts. At first they told me they couldn’t deliver because the roads weren’t good enough, but an hour later I got a call from the owner: “We’re in the goddamn wood business. We’ll plank the road.” That’s what they did.

Steve Butler

After two and a half months, we finally got heat in the building: big propane heaters with fans to circulate the air. They were the only things inside the place; everything else had been cleared out. When we left that evening, I was smiling, and I told Bev, “We might not have hot water tomorrow, but we’ll have warm hands to work with.” That was November 15th.

The next day I came in and saw that the ceiling had started to fall down. The building had been drenched with demolding chemicals, and the moisture from the attic had been drawn down into the Sheetrock. It was the only time I was nearly brought to tears. But then I started laughing out loud. Bev looked at me and said, “What’s wrong with you?” “Look on the bright side,” I said. “Now we’re going to get a new ceiling.”

Lisa Sullivan

For so long we were just riding this adrenaline to get things done. But eventually that goes, and I remember just reaching a point that winter where I thought, I can’t bear to do another thing. We’re still a total disaster. I didn’t have it in me to go to another meeting about the recovery or do any more work. So I took a few months and just did some more things with my kids, who’d probably felt neglected. I mean, all through that fall we were making grilled cheese for dinner at 8 o’clock at night and then just crashing. It felt important to take a step back and just feel normal again.

‘it was like being hugged, when you walked into that building’

Slowly, things did get better. At the center of the recovery effort was the emergency shelter that had been established at the high school. The early visitors were a group of wedding guests who’d been stranded in town and a National Guard troop that arrived via high-water vehicles. Cots were set up in the gymnasium. In the library, sophomore Hannah Swanson oversaw a free child-sitting service, and the school’s head cook, Joe Girardi, churned out food for anyone who came through the doors. The whole experience was punctuated by a community supper every night, where exhausted residents could catch their breath and take solace in the fact that they weren’t alone. “It was this incredible time of fellowship,” recalls Nicki Steel, a local photographer.

It was also from there that Steel dispersed an army of volunteers, and leaders like Monique Johnson and Camille Swanson welcomed donations. Even those who’d had little connection to the town offered something. A bakery in Bennington delivered fresh bread every day, while truckloads of clothes came from Springfield, Vermont, and Portland, Maine. Offers of help came in from people around the country.

Wilmington’s community-wide recovery effort would continue for months, from a benefit concert called Floodstock that raised $80,000, to a group of second-home owners who pooled together money to help local businesses rebuild. Friends of the Deerfield Valley, a nonprofit, alone raised $175,000 for Steve Butler’s North Star Bowling.

Monique Johnson

That first night we tried making spaghetti in the home-economics room, where they had two regular-size ovens. But the school lost power, and we were running on a generator, so we couldn’t get the water to boil. A police officer rode in the bucket of a bucket loader to Shaw’s to get cold cuts and bread. For water we had only the drinking fountains, which we knew wasn’t going to be enough, so another officer took the butt of his gun and smashed open the drink machine. So that first night we were making sandwiches and stealing energy drinks out of the cafeteria.

Susan Haughwout

There was one young woman who was having a panic attack—shaking, feeling faint—and she had a bad cut. I’d heard that among the wedding guests there was a doctor, so I went into the gymnasium and asked, “Is anyone here a doctor?” A young guy, probably 30, raised his hand. “Well, I’m an anesthesiologist,” he said. “Good enough,” I told him. “We have a triage issue in the cafeteria, and we need your help.” He ended up spending quite a bit of time with the woman and helping her out.

Monique Johnson

Because it was the end of summer, people were dropping off all this extra produce from their gardens. One day we got a big box of peaches, and somebody took them home and made peach cobbler. Joe turned a bunch of donated heirloom tomatoes into this amazing salad. Any time of day there was food available—desserts, sandwiches, anything you could imagine. The building took on a life of its own.

Nicki Steel

It became magical the way things happened when we needed them to. One day a woman who was helping out in the kitchen came back from her break in tears. On her way home she’d passed a family doing laundry in a bucket in their front yard. She ended up stopping and taking their clothes home to wash them. I was like, “Oh my God, I bet there’s a lot of people who can’t do their laundry.”

Literally as we’re discussing this, a woman from Mount Snow—I didn’t even know her—happened to overhear me and said, “I can help with that.” She took out her phone, made a call to someone, then handed the phone to me. “This is Ruby from Mount Snow housekeeping” was the voice on the other line. For the next three days they drove down, picked up bags of dirty clothes from residents, and washed them in their big industrial machines.

Camille Swanson

Everyone wanted to help. If you said you needed something once, the next thing you knew, some big truckload would come and deliver it. We needed some diapers; well, before you knew it, 4,000 diapers were being dropped off. It was like, Oh my God.

Steve Butler

I’ll never forget it. They were serving gourmet food—to anyone who walked in the door. And the atmosphere—all those volunteers made you feel like the most important person in the world. It was an unbelievable feeling. It was like being hugged, when you walked into that building. It felt so good.

Monique Johnson

One of the big network news shows came to town, and they wanted to know if there was one person they could highlight for their person of the week. I remember thinking, There’s no single person to feature; it’s everybody. Everybody came together. They put on their boots and did what needed to be done.

Susan Haughwout

We’d had, in the years before the flood, a couple of controversies in town that had created divisions. For some, it was quite serious. They maybe weren’t as friendly with people as they once had been. But during this time of recovery, of coming together and helping out, that all disappeared. It was like this wonderful time of renewal.

Camille Swanson

That last day there was bittersweet. I think we were all kind of sad. There had been such a purpose in our lives. We were in this bubble with total focus. It was so cool to be in a situation where nothing matters except where you are at that moment in time. When it was over, I think we all sort of wandered around aimlessly a while after.

‘I still have nightmares’

Five years after Irene, Wilmington is thriving. Businesses like Dot’s, North Star Bowling, and Bartleby’s Books are in completely renovated homes, while new restaurants and a hotel have recently opened. But residents watch the river more closely when a big rain hits. There’s added sympathy when the news reports about some community having suffered a weather event, and in downtown Wilmington there’s a bench that honors the life of Ivana Taseva. On the police station, above the Hurricane of ’38 mark, there’s a line that indicates the new record flood line, 71 inches. As it was for those who lived through the Hurricane of 1938, the memory of what the storm brought endures.

Lisa Sullivan

Four months after the flood, Anna, my store manager, and I went to the American Booksellers Association conference in New Orleans. The entire time we just kept thinking, Here we are where Katrina hit, and what happened to us was just this tiny version of what they had experienced. We rented a car and drove around the Ninth Ward. Here it was, six and a half years after the hurricane, and the place was still devastated. So many of the homes were still rough, and people were walking because bus service hadn’t returned. It gave us perspective. Our houses are okay, we have cars, and people haven’t had to move hundreds of miles away in order to live.

Dana Stone

I haven’t really found any peace. I still have nightmares about the accident. Every year around when it happened, I get real shaky. My heart sometimes starts pounding.

Hannah Swanson

My friends and I think of the storm as this kind of passage from childhood to adulthood. Like there was our life before the flood and there’s our life after it. During that storm, a lot of us had to take on all these new responsibilities, and I don’t think any one of us ever felt like we came back to what life was like before Irene hit us.

Steve Butler

I’m the most humble, thankful, grateful person in the whole wide world. I wasn’t born or brought up here, but I got more help than anybody should rightfully expect for 10 lifetimes.

Nicki Steel

For months after the storm I didn’t want to take any pictures. It felt like the landscape here had been so changed. You’d be going through your life, not really thinking about the storm, then you’d drive around a corner and see something that was devastated and be reminded of it again. I’ve talked to other artists who’ve felt the same way.

It wasn’t until a year after the storm, when I was up in the Northeast Kingdom, that I felt the adrenaline rush to shoot again. I ended up creating a series of images I call Hearts in Nature. They’re shots of naturally occurring things that are in the shape of a heart. I didn’t set out to do it, but I guess it was part of the healing process.

Susan Haughwout

We created a list of the records we knew were lost, so that we could leave a record behind for future clerks, who wouldn’t have gone through the experience with us and wouldn’t know, when they went to look for something, why they couldn’t find some document. There are gaps. So when someone goes to look for, say, the Board of Civil Authority minutes from, you know, 1995 to 2011, they’ll find a little note saying, Well, it would be nice to have those, but they were lost in the flood.

Florence Crafts

I guess some people thought that I shouldn’t have fixed my house up, that it wasn’t worth it. But it’s my home. And if it happens again, I won’t be here. And if I am, I’ll be too old then, and I’ll just pack my bag and move out. I’ll let somebody else take over.

Nicki Steel

That first Saturday morning after the storm, I went downtown with paints and a brush to mark where the flood level had risen to. After all we’d gone through, after that whole first week, I felt like I needed to do that. For so long we’d looked at that ’38 mark and couldn’t imagine that the waters had ever gotten that high. And now we’d been through something where the water had gotten above that. I guess that by painting that new mark, I wanted to show that this had happened to us. That we had survived.

Ian Aldrich

Ian Aldrich is the Senior Features Editor at Yankee magazine, where he has worked for more for nearly two decades. As the magazine’s staff feature writer, he writes stories that delve deep into issues facing communities throughout New England. In 2019 he received gold in the reporting category at the annual City-Regional Magazine conference for his story on New England’s opioid crisis. Ian’s work has been recognized by both the Best American Sports and Best American Travel Writing anthologies. He lives with his family in Dublin, New Hampshire.

More by Ian Aldrich