New England’s Vampire History | Legends and Hysteria

Audiences swoon for them in books and onscreen, but when New England had a “real” vampire panic, there was nothing romantic about it. Read more about New England’s vampire history.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

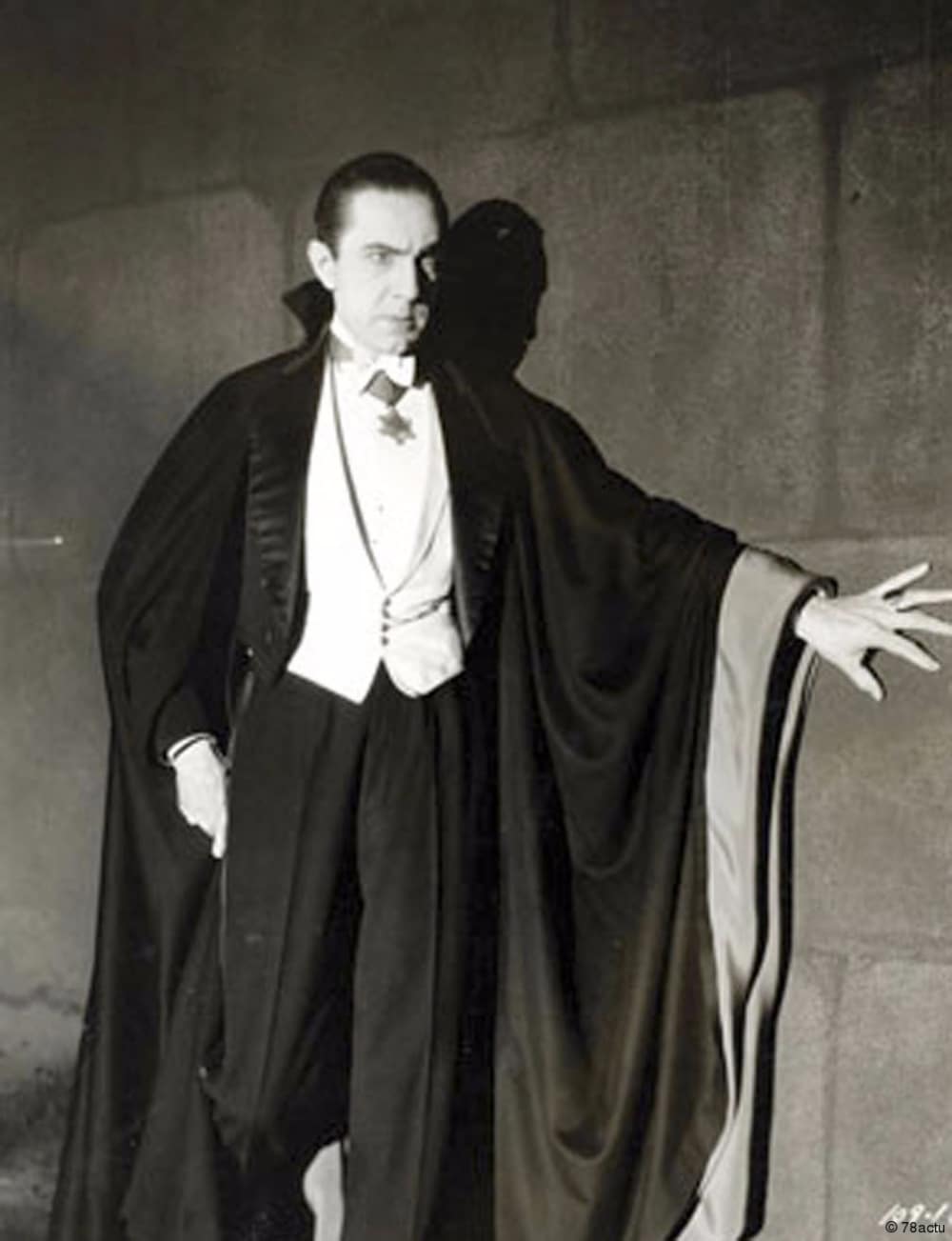

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanVampires are an omnipresent part of today’s popular culture. We tune in to watch them battle handsome werewolves, seduce the young and innocent, and sometimes get their butts kicked by a cheerleading slayer. In the 1960s, the popular TV show Dark Shadows told the spooky but melodramatic tale of Maine vampire Barnabas Collins and his family; Stephen King’s 1975 horror novel, Salem’s Lot, likewise revolved around a vampire enclave in Maine. More recently, the 2006 movie The Covenant offered a story of vampires at a Massachusetts prep school. But did you know that New England actually has a long vampire history? In fact, there was a time when Rhode Island was considered the “Vampire Capital of America.”

Vampire History in New England

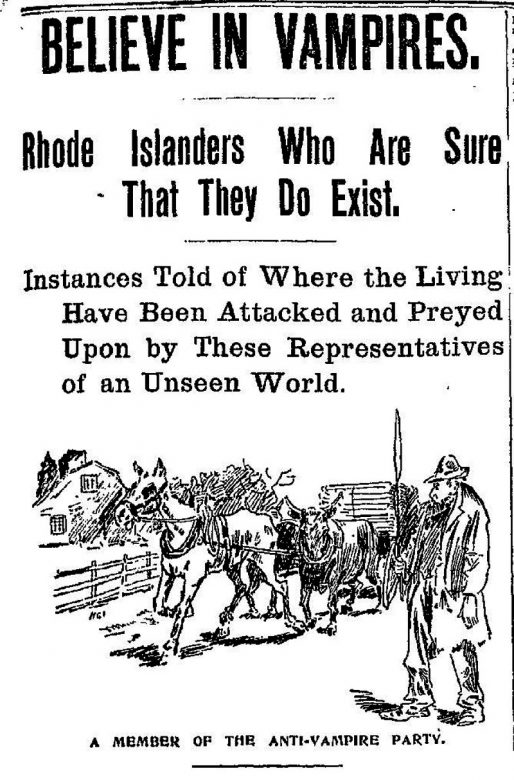

New England vampire history and hysteria kicked off a full century after the region’s better-remembered witch trials, and although Rhode Island was seemingly the epicenter, it was a region-wide phenomenon. The New England vampire panic that started in the 1790s built upon earlier “outbreaks” in Europe, as communities grasped for explanations for infectious diseases before such illnesses were scientifically understood.

Photo Credit : Wikimedia Commons

In early New England, the disease that we now know as tuberculosis was commonly called “consumption.” The classic symptoms are a chronic, sometimes bloody cough, along with fever and weight loss. To helpless loved ones, it appeared as though the victim was withering away — aka being consumed. Without medicine to slow its spread, TB was a devastating affliction. By the dawn of the 19th century, it was responsible for approximately one out of every four deaths in the eastern U.S. To this day, tuberculosis remains the world’s most deadly infectious disease, responsible for well over a million deaths each year.

Based on what they were seeing (and a good dose of superstition), many early New Englanders believed that vampires, not disease, were responsible for the symptoms. Of course, not everyone bought into the superstition: In June 1784, a letter to the editor of The Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer from a Willington town councilman cautioned readers against being misled by a “quack doctor” who encouraged families to dig up and burn dead relatives to stop consumption from spreading (legend being that the surest way to stop a vampire was to burn its vital organs).

Photo Credit : Wikimedia Commons

New England Vampire Legends | Vampire History & Hysteria

Rachel Harris | Manchester, Vermont

One of the earliest known cases of New England “vampirism” to have a name attached to it was that of Rachel Harris, who died of tuberculosis in 1790. The year after her death, her widower, Captain Isaac Burton, married her stepsister, Hulda. Before long, Hulda began exhibiting symptoms similar to Rachel’s, and family and friends therefore reasoned that Rachel was the culprit. In February 1793, more than 500 Manchester residents braved frigid temperatures to watch the liver, heart, and lungs be removed from Rachel’s exhumed corpse and burned on a blacksmith’s forge. According to some versions of the tale, portions of the organs were preserved to make a medicine for Hulda. Regardless, she died that September. Following her death, did the good people of Manchester realize the error of their ways? Sort of: They reasoned that perhaps Rachel hadn’t been a vampire at all, but rather a witch.

Abigail Staples | Cumberland, Rhode Island

In February 1796, the Cumberland town council granted permission for Stephen Staples to exhume the body of his 23-year-old daughter, Abigail, who had died of consumption. Shortly after Abigail’s death, her sister, Lavinia, had started showing the familiar symptoms of consumption. Lavinia told of dreams in which a shadowy figure sat heavily on her chest and drew out her breath; during one of those dreams, she reportedly called out Abigail’s name. The town officials consented that Staples could “try an experiment” to save Lavina’s life, despite noting the decision was made “against the better conscience of this council.” There is no record of what came of the exhumation — or, for that matter, of Lavinia.

The Spaulding Family | Dummerston, Vermont

In his journal entry of September 26, 1859, Henry David Thoreau noted, “The savage in man is never quite eradicated. I have just read of a family in Vermont – who, several of its members having died of consumption, just burned the lungs and heart and liver of the last deceased, in order to prevent any more from having it.” At the time, Thoreau himself had long been battling tuberculosis, of which he would die three years later (although in his case no one seems to have suspected vampire involvement). As for the episode to which Thoreau referred, it’s likely the 1790s ordeal of the Spaulding family. Having lost six of his 11 adult children to consumption, Lieutenant Leonard Spaulding was desperate. When yet another daughter grew ill, the body of the most recently deceased child was dug up and the vital organs removed and burned. Incidentally, one vampire-adjacent belief of the day was that vines would grow between buried caskets, and that once all of the burials in a plot had been so connected, another family member would die. When Spaulding’s son Reuben was buried in 1794, his grave was set apart from those of his other family members, possibly to break the chain.

Photo Credit : Wikimedia Commons

Sarah Tillinghast | Exeter, Rhode Island

Sarah Tillinghast was the first of “Snuffy” Tillinghast’s 14 children to die. When his surviving children claimed that Sarah continued to visit them at night, it might have seemed part of the natural grieving process. But by 1799, five more Tillinghast children had died of consumption and another was gravely ill. When the bodies of the dead were exhumed, all except Sarah were found to be in advanced stages of decomposition. Her heart was removed and burned in front of the family home. Describing the episode decades later, in 1888, writer Sidney Rider observed that “peace then came to this afflicted family, but not, however, until a seventh victim had been demanded.”

Nancy Young | Foster, Rhode Island

After Nancy Young died at age 19 in 1827, her sister “commenced a rapid decline in health with sure indications that she must soon follow [Nancy to the grave].” When Nancy’s other siblings began to decline, their father, Captain Levi Young, asked his neighbors and friends to exhume and burn her remains “while all the members of the family gathered around and inhaled the smoke from the burning remains.” This cure apparently did not work, as five more children died.

The Ray Family and “J.B.” | Jewett City, Connecticut

In 1845, 24-year-old Lemuel Ray died of consumption at the age of 24. His death was followed by that of his father a few years later, and then his brother. Three years later, when Lem’s oldest brother, Henry, fell ill, the family took drastic measures: exhuming and burning. Henry died despite their efforts.

Interestingly, an accidental discovery in the 1990s suggested that perhaps the Rays were not the region’s first “vampires.” Just a few miles from the Ray farm, some kids discovered a skull. Further investigation revealed an unmarked graveyard where 29 bodies were buried. Archaeologists determined that one of the bodies, which showed signs of tuberculosis, had been dug up and reburied with the head removed and turned face down, and the femur bones arranged on the chest in the shape of a cross formation. The only marking on the grave was the initials “J.B.”

Mercy Brown | Exeter, Rhode Island

The best-documented case of suspected vampirism in New England was that of Mercy Brown, whom we’ve written about before. In 1883, Mercy’s mother died of consumption. Seven months later Mercy’s 20-year-old sister died, and a couple years after that both Mercy and her brother Edwin grew ill. Edwin was sent away to recover, but Mercy soon died. Mercy’s father, George, was by then desperate to save his remaining children and — though he was said not to believe in vampires — consented to have his family’s bodies exhumed. As The Providence Journal reported on March 21, 1892: “Dr. Harold Metcalf, the medical examiner of the district, who examined the bodies … is not one to believe in the vampire superstition…. He made his examination … without exceptional results, according to his own belief, but found in one of the bodies, to the satisfaction of many of the people down there, a sign which they regarded as proof…. When he removed the heart and liver from [Mercy’s] body, a quantity of blood dripped therefrom. ‘The vampire,’ the attendants of the doctor said — and then, conforming to the theory of the necessity of destroying the vampire, burned the heart and liver.”

As it happened, the New England vampire scare started winding down toward the end of the 19th century. Perhaps not coincidentally, this was around the same time that Robert Koch identified the bacteria responsible for causing tuberculosis.

What’s your favorite tale of vampire history in New England?

This post was first published in 2018 and has been updated.

I don’t know of a real connection but the story of “Dark Shadows” from the tv soap took place in southeastern Massachusetts and in the town of Westport there is a cemetery where the Collins family is buried. I saw the cemetery years ago when I lived in that area. It would be interesting if research showed there was an actual connection and some inkling of the truth.

Actually, “Dark Shadows” took place in the town of Collinsport, Maine, 50 miles east of Bangor on the coast in Hancock County. This fictional town would be just north of Mount Desert Island. The Collins family mausoleum on the TV series was located at Eagle Hill Cemetery.

I understand the stake through the heart method of killing a vampire started in Rhode Island when it was said a vampire could only be killed by denying it blood for sustenance. The stake would be driven into the exhumed body through the bottom of the casket into the earth. Presumably to keep the suspected vampire from leaving its grave to hunt for victims. Supposedly they only hunted at night because they would be recognized by townspeople who knew that they had died. Vampires were not believed to be killed by sunlight, garlic , holy water or anything except starvation.

Supposedly corpses can continue to grow their fingernails for a short time, and when caskets were opened, and people saw the longer fi gerbils and toenails, they assumed the corspe was the ,iving dead. There was another issue too which corpses undergo that would make it seem like the person was still roaming the earth, but I can’t remember now. Likely the towns where vampirism was suspected was made up of Europeans who had superstitious beleifs about the undead. Likely a small community of natu4zlizwd citizens from foreign countries with such beleifs. There was also werewolf scares too around the country. (Plus of course witches and warlocks scares that ended badly for innocent people too)