Innovations & Ingenuity | New England’s Gifts

New England Innovations | People and Deeds That Have Inspired a Nation The mosaic-making robot doesn’t have fingers, just a single suction cup that has a sure touch with glass and ceramic tiles. It plucks them from a tray and places them into a 12-inch-by-12-inch grid, creating abstract patterns or recognizable images. Standing next to […]

Photo/Art by David Julian

New England Innovations | People and Deeds That Have Inspired a Nation

The mosaic-making robot doesn’t have fingers, just a single suction cup that has a sure touch with glass and ceramic tiles. It plucks them from a tray and places them into a 12-inch-by-12-inch grid, creating abstract patterns or recognizable images. Standing next to the steel cage that houses the robot is Ted Acworth. He points to a next-generation robot across the room.

“It’s 10 to 20 times faster than the original one,” he says, “but we haven’t filed the patents on it—so no pictures.”

If Acworth had started a company two centuries earlier, no doubt it would have been a water-powered textile mill, turning the craft of weaving into a high-volume business. In 2015, his company, Artaic, is having much the same effect, reducing the cost and speeding up the time required to create a custom-designed mosaic for an office lobby or the master bath of a vacation home.

Artaic and the other start-up businesses that are its neighbors in a former Army supply depot on the edge of Boston Harbor are only the youngest shoots from a tree that has been growing in New England for a few centuries now. Just across the water from Artaic was the shipyard where Donald McKay built the fastest vehicles on earth—clipper ships—in the mid-1800s. Go up the Charles River a half-mile and you’re at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, whose labs designed the radar systems that helped the Allies win World War II, and also the guidance computer that helped Apollo spacecraft reach the moon. Farther up the river in Waltham is Route 128, the highway that in the 1980s was home to many of the companies that first introduced computers and productivity software to the workplace.

New England doesn’t have a monopoly on ingenuity and entrepreneurial drive, of course, but we’ve been at it longer than many parts of the world. And almost every week, you can bump into a delegation visiting from Madrid or Dubai, poking into Harvard’s labs and the start-up workspaces nearby, trying to figure out the formula that produces both important scientific breakthroughs—such as cancer-hunting nanoparticles—and also high-paying jobs.

The formula isn’t complicated, just very hard to copy: start a few universities, and give them a century or three to get very good at attracting the best professors and the smartest students, and also research money from government agencies and large corporations. When students or professors start businesses, make sure there are investors nearby willing to take risks on unproven ideas. Lawyers who can file patents are essential, as is cheap office space in old mill complexes or Army warehouses.

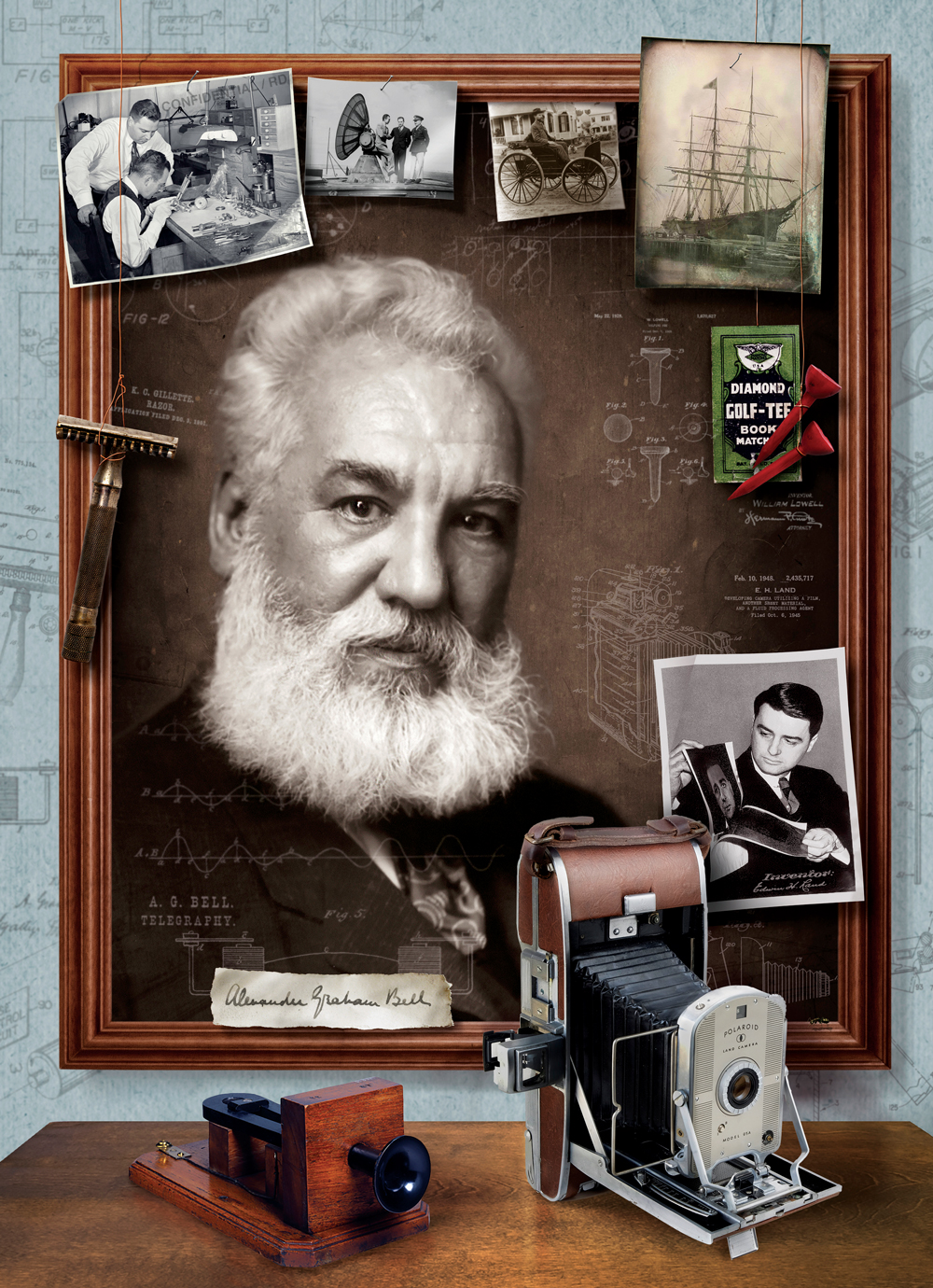

It gave us the telephone; Alexander Graham Bell was a Boston University professor renting cheap space above a telegraph supply shop. It gave us The Wizard of Oz; two of the three founders of Technicolor were MIT alumni whose first office was in a railroad car, so they could hook it to a train and go wherever someone might be crazy enough to want to make a motion picture in color. Harvard was less supportive of entrepreneurial faculty in the 1980s than it is today, so one of the founders of Biogen left his teaching position for a few years to help pioneer the modern biotech industry. The company today sells several drugs that treat multiple sclerosis, and may be getting close to one that slows the progress of Alzheimer’s disease.

Most of New England’s entrepreneurial activity orbits university campuses like electrons. In Burlington, Vermont, a team of recent Middlebury College graduates is building software that can convert architectural plans into three-dimensional digital environments; put on a virtual reality headset and you can amble through structures that haven’t been built yet, turning your head to see out windows or down hallways. In Manchester, Southern New Hampshire University is filling brick mill buildings with software developers, designers, and counselors who run two different online colleges, with faculty and students across North America. Two Brown University seniors built a website that would collect orders for T-shirts and produce them only when enough orders came in; they’ve now raised more than $55 million in venture-capital funding for their company, Teespring, headquartered in Providence.

A few blocks from the heart of the MIT campus in Cambridge, there’s a two-story brick building called LabCentral that’s filled with 29 young biotech businesses that share expensive lab equipment. One tenant is Vaxess Technologies, which is using a protein found in silk to stabilize vaccines, so that they can be transported and stored without refrigeration. The founders are from Harvard, though the original scientific breakthrough was made by professors at Tufts University.

Leading a tour of LabCentral, co-founder Johannes Fruehauf mentions that one of the building’s prior tenants was Edwin Land, the inventor of instant photography, who maintained his private research lab here. But as is often the case in New England, there are layers beneath layers. Before Land’s lab, the building was on one end of the first “long distance” telephone call, between Alexander Graham Bell in Boston and his assistant, Thomas Watson, in Cambridge. And the rails that serve as lintels for many of the building’s windows refer back to the original tenant: Kimball & Davenport, the first builder of passenger railroad cars in America.

The building, and the region, has always been home to “people who aspire to do great things,” in Fruehauf’s words. And something about the history, Fruehauf says, needles his tenants a bit when they show up to work every morning: “Guys, there have been smart people here before you. You’ve got to live up to the challenge.”