Lost Towns of the Quabbin Reservoir

The lost towns of the Quabbin Reservoir aren’t your typical ghost towns. Learn why they were abandoned, and how they came to be under water.

The Dana Congregational Church was once an integral part of the town. Now, just some stones and the path that once led to its front door remain.

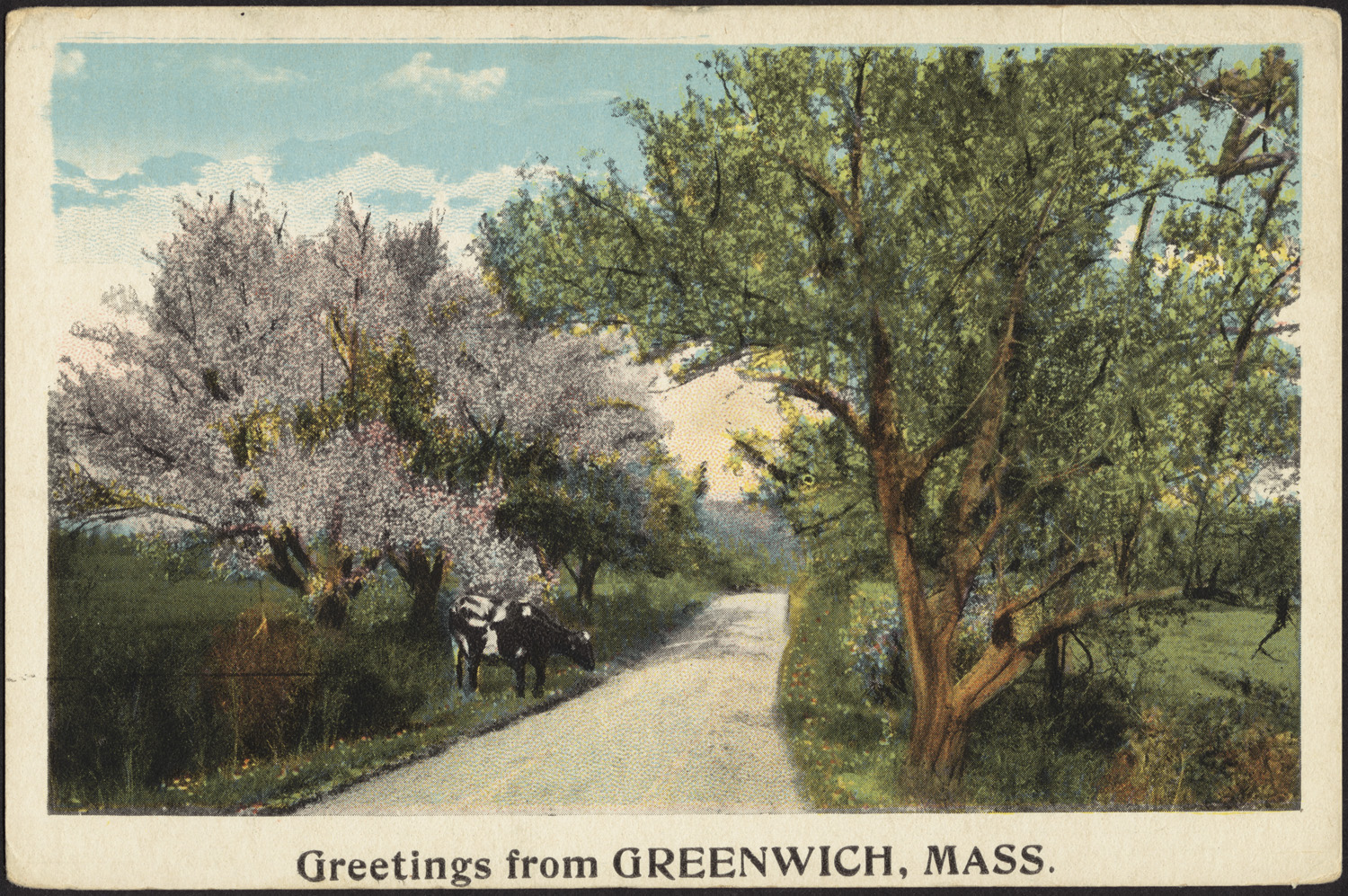

Photo Credit : Bethany BourgaultThe four lost towns of the Quabbin Reservoir — Dana, Enfield, Greenwich, and Prescott — are not your typical “ghost towns.” You won’t find dusty streets, old saloons and blowing tumbleweeds here. After all, these ghost towns are underwater. They teem with life, but not the human life that they once supported. The foundations remain, but their former residents have long since settled elsewhere.

Photo Credit : Boston Public Library

Lost Towns of the Quabbin Reservoir

The Quabbin area was settled in the early 1700s, and grew to a population of about 2,700 by 1938. It was well on its way to prosperity, despite hard hits from the Great Depression. But there had been talk of the area’s demise for years — since at least 1922. The eastern part of the state needed drinking water, and the government needed a place to put it. The Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission had its eye on the Swift River Valley, and there wasn’t much that the residents felt they could do to divert its gaze.

Initially, the residents thought they would be safe. The scope of the project — relocating all those people and the homes, schools, churches, and shops that they and their ancestors had worked for so long to develop — would surely cause the government to look elsewhere. As if that weren’t enough, they would also have to exhume and relocate 7,613 bodies from local cemeteries. Surely there was a better solution.

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

The Swift River Act legalized the impossible, though, and after its passage in 1927, residents of the valley faced a hard deadline. They had until April 27, 1938 to pick up and move their entire livelihoods elsewhere, aided by a governmental allowance of $108 per acre lost. That night, a ball was held in the town of Enfield to give the residents one last night together as a community. Those who were unable to get tickets danced to the music on the Town Hall’s lawn — no one was going to miss this event. When the clock struck midnight on April 28, the towns were legally no more. The flooding began several months later.

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Today, the Quabbin Reservoir is 39 square miles of gorgeous lake landscape. It holds 412 billion gallons of water, picking up another 1.6 billion for every inch of rainfall. It continues to serve as an irreplaceable water supply for eastern Massachusetts residents. Though it is no longer the largest manmade source of water in the world, it is still among the largest in the region.

The last of the towns’ residents moved out in late 1938 (some were delayed by that year’s infamous hurricane). The promise that their sacrifices would be for the greater good was just a small offset to the bitter sadness they felt about being forced out of their homes. Those who had lived out their entire lives in the area felt the loss most deeply — the flooding process took several years, meaning that some would never get a chance to go back. Younger residents who were eventually able to visit found some comfort in the area’s new, natural beauty, but felt the sharp sting of nostalgia all the same.

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

The road to the old town common in Dana is now one of the most highly trafficked trails near the reservoir. Much of Dana, including the common, was at enough of an elevation that when the waters came, it stayed high and dry. What remains is a small, triangular patch of grass marked by memorials and cellar foundations. Photos of the buildings as they were before the flooding show visitors what they would have been looking at, had they planned their visit 80 years earlier.

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

The easiest way to reach the area is to park at Gate 40, off of Route 32A in Petersham, and take the 1.7-mile stroll down Old Dana Road. Once there, visitors can see the foundations of old homes, the school, town hall, the Eagle Hotel, and a field where the cemetery once was. The bodies that once occupied this plot of land now reside in Quabbin Park Cemetery in Ware.

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Each cellar has a story; each foundation gives a clue about lives lived long ago. Some are easy to miss — the treetops emerging from their depths appear to be bushes. Others remain more fully intact, a testament to the craftsmanship of those who built Dana all those years ago.

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Photo Credit : Bethany Bourgault

Surviving residents, who, over the years, have worked to ensure that their hometowns will not be forgotten, are now in their 90s. They’ve organized reunions and dedication ceremonies, erected monuments, and maintained trails. Informative books, educational tours, and a welcoming visitor center have helped to secure the area’s history in the consciousness of the next generations, perpetuating the countless stories of the towns that history almost forgot. Now, many descendents of those residents have taken on the task of preserving those stories, too.

You certainly don’t have to be a descendant of the Quabbin towns to enjoy the area, though. The natural, forest environment has made the Quabbin Reservoir a desirable resource for local fishermen, explorers, and naturalists. Be sure to read up on the rules of the trails before your visit — some trails don’t allow dogs or bikes. It’s also worth doing some research on the stories that have been shared over the years. That way, when you’re in the area, you can see what they once saw.

It’s the best way to make a “ghost town” come back to life.

The Dana town common can be reached on foot less than two miles from Gate 40, off Rt. 32A in Petersham, MA. Check out the WGBY/PBS documentary, “Under Quabbin” for a unique look into the reservoir’s waters.

This post was first published in 2016 and has been updated.

SEE MORE:

Nine Men’s Misery | A Historic (and Possibly Haunted) Site in Cumberland, RI

Mount Wachusett Ghost | The Legend of Lucy Keyes

Wayside Inn Ghost | Real or Imagined?

Bethany Bourgault

Bethany Bourgault interned with Yankee Magazine and New England.com during the summers of 2015 and 2016. She recently graduated from Syracuse University, majoring in magazine journalism with minors in writing and religion. She loves reading, exploring the outdoors, ballroom dancing, and trying new recipes. Keep up with her adventures at bethanybourgault.com.

More by Bethany Bourgault