Lac-Mégantic Tragedy | The Town is Gone

When an oil train derailed just over the Maine border in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, it ignited a horrific inferno that took 47 lives and forever changed the community and its people.

More than 180 firefighters were dispatched from around Quebec and northern Maine in an attempt to control the devastating fire.

Photo Credit : François Laplante-Delagrave/AFP/Getty ImagesIn the early-morning hours of July 6, 2013, a train carrying more than 10,000 tons of crude oil derailed and exploded in the small town of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, just across the Maine border. What happened in that moment claimed the lives of 47 people and changed the town forever. The aftershocks continue to be felt everywhere in New England where freight cars rumble past.

Photo Credit : François Laplante-Delagrave/AFP/Getty Images

It was the tail end of the first warm day of summer.

And it was a Friday, the crowd was young, the weekend was just ahead–and on the outside terrace of the Musi-Cafe on rue Frontenac in Lac-Megantic, Quebec, even as Friday turned to Saturday, there was still not an empty table.

Or inside, either, where singer/guitarists Guy Bolduc and Yvon Ricard, both now in their forties, hadn’t been off the stage since 9:30. The two, who had gotten their starts in the town’s more honky-tonk bars two decades before and were loved here now as native sons, were playing together tonight for the first time in years. They’d begun the night with a love song–“Rosie” (“Oh Rosie, tu est blanc / Tes yeux m’eclairent / De t’avoir eu un instant / j’etais tellement fier …”), a Quebecois favorite–then moved to the dance tunes that had kept the floor filled for most of the past three hours.

“A perfect evening,” Karine Blanchette, one of the waitresses, would remember later. “Everyone was floating.”

It was a local crowd. There was Stephane Bolduc’s birthday group–he was 37, a widely loved car salesman, nearly destroyed by bereavement only two years before, there tonight with his new girlfriend, Karine Champagne; Genevieve Breton, 28, a green-eyed blonde who “sang every hour of the day,” had found brief fame on Star Academie, Quebec’s version of American Idol, and was now working in a jewelry store down the street; Gaetan LaFontaine, his two brothers, his wife Joanie Turmel, and Joanie’s aunt Diane Bizier, also there to celebrate a birthday; Natachat Gaudreau, 41, a single mother who worked for the town’s school board, and was lately talking of opening a hostel; Mathieu Pelletier, 29, a local math teacher, hockey coach, and father of a 3-year-old. And a secretary, an art teacher, a drummer; a French teacher and a daycare worker out tonight on their first date; a pharmacy worker, a stonecutter, a steeplejack, a second daycare worker; two waitresses, at least three students, and several employees of the particleboard factory and door manufacturer in town.

At 10 minutes after 1:00 in the morning–July 6 of last year–the two musicians announced to the crowd that they’d be taking a half-hour break. Guy Bolduc looked briefly at his old friend as the two left the stage together: “Man, it’s fun to play with you.” Then he moved off toward the bar.

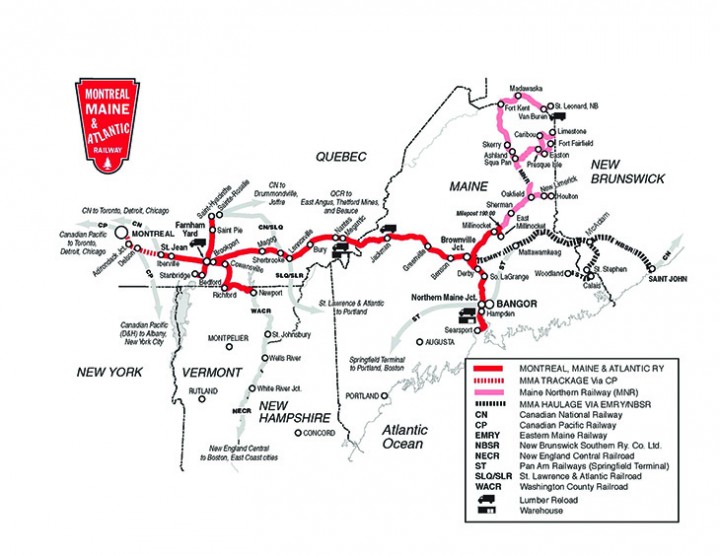

More than two hours earlier, on a rail track in the village of Nantes, seven miles northwest, Thomas Harding, an engineer for the Montreal, Maine and Atlantic (MM&A) Railway, was putting his train to bed for the night. It was a big train: five locomotives and a car just behind to house the radio-control equipment, followed by a loaded boxcar and 72 carbon-steel tanker cars, each carrying 30,000 U.S. gallons of Class 3 petroleum crude–10,300 tons in all, nine-tenths of a mile front to back, bound for the Irving Oil refinery in St. John, New Brunswick, roughly 300 miles east.

Photo Credit : Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway, Inc.

There were plenty of trains just like it–some as long as two miles–most of them coming from the same place: North Dakota’s Bakken oil fields, where a boom in shale-oil production (the result of what has come to be known as “fracking”) has created a massive, nearly overnight run on rail freight. Roughly 400,000 carloads of crude were shipped last year on U.S. railroads, much of it through New England to refineries in Canada or the Northeast U.S.–up from fewer than 10,000 five years ago. Some 7,400 carloads went across the state of Maine alone–through Jackman, Greenville, Brownville Junction, and other small towns forming an east/west belt across the middle of the state. More than half of those carloads were transported behind MM&A locomotives headed east to Irving’s St. John refinery.

The tide of oil hadn’t gone unnoticed. Just a week before, on the night of June 27 in the central-Maine community of Fairfield, protesters had erected a large wood-framed sign–Stop Fracked Oil--across the tracks in the center of town, to block a train carrying nearly 100 carloads of crude to the same St. John refinery. Six of the group were arrested. “Our concern is [that] the rails aren’t safe,” one of them, a 64-year-old protester from Verona Island, told the press.

Tom Harding, as permitted by MM&A’s work rules, was the train’s only crew member that July night in Nantes. By the time he had parked it, shut down four of its five locomotives–the lead engine left on to keep pressure supplied to the air brakes–and applied hand brakes on what would later be claimed were 11 of the 72 tanker cars, it was probably around 10:45. His work done, he phoned a taxi to take him the seven miles to Lac-Megantic, where he had a room reserved for the night. As the cab pulled away, its driver would tell police later, the lead locomotive was spitting black smoke.

At 11:30, a 911 call was received: in Nantes, a passerby reporting fire in the train’s lead locomotive. The village fire department responded to the call, shut down the lead engine, extinguished the blaze, and then phoned to notify MM&A of what had taken place. Not long after midnight, two of the railway’s track maintenance crew arrived from Lac-Megantic. They confirmed that the train was secure. At a few minutes before 1:00, the firemen left the scene.

It’s not clear why what happened next happened. One theory is that the air brakes were disabled when the firemen shut down the lead locomotive. Others claim that the hand brakes, not the air brakes, are the critical safety system on an idled train: that if they’re set properly (and enough of them are set), the train will stay in place, even on a grade.

And there was a grade–a barely perceptible, 1.2 percent grade. Nantes is 1,690 feet above sea level. By the time you reach rue Frontenac in Lac-Megantic’s downtown, you’re at a little less than 1,350 feet. And somewhere around 1:00 a.m., unseen on the darkened track, ever so slowly at first, the big train began to roll.

—

Yves Laporte, 60 years old this year, is a window on both a region and a time. In the living room of his home in Marston, on the northwest shore of Lac Megantic, sits a crude, 100-year-old rocker, probably made of birch limbs. “It’s not the most comfortable chair in the world,” he says, “but I like to look at it sometimes.”

The chair was made by his grandfather, Joseph Cliche, and sat on the porch of the home his mother grew up in, on Lac Megantic’s northeast shore a little less than a century ago. The lake, from which the town gets its name, is nine miles long by roughly two miles wide. In a photo he keeps of the house, the chair sits empty on the porch next to his grandmother, who is standing, while the rest of the family–his grandfather in work clothes and broad-brimmed hat; his mother, who appears to be around 9, in braids and leggings with a book on her lap; and several younger brothers and sisters–look out at the camera from their spots at the front of the house. It’s summer, with tall birches overhanging the scene.

Yves lived in that house for several years as a boy. He lives today across the lake from it, in the two-story home, surrounded by birches, that he built with his first wife 38 years ago. His grandfather Joseph, with a brother, Yves’ great-uncle Philibert Cliche, started a broom-handle factory here around 1912, then expanded into clothespins and plywood; by the 1930s it was the largest employer in town. Joseph lies buried in Lac-Megantic’s Sainte-Agnes Cemetery. Yves’ paternal grandfather, Henry Laporte, set up shop here as a baker around 1900, then owned a livery stable and a general store. He also is in Sainte-Agnes. His father, Henry Paul Laporte, ran a sporting-goods store in town, sold gas, and rented out cottages.

“The lake is in my blood,” Yves says, as he finishes recounting the last of his ancestors. “It is in my family’s blood.”

Most people you meet here will tell you a similar story. This isn’t a place you just end up in or pass through. If you’re here today, it’s likely because your father was here 50 years ago–was a logger or a barber, or worked in a pulp mill or the railyards–and his father 50 years before that. It’s a hard place to live, on the northern slopes of the Appalachians in southeastern Quebec, the largest town for 60 miles in any direction, where the temperature can drop to 40 below in January and the snows that come in October last sometimes into May.

The earliest white settlers, most of them fishermen and farmers, from Scotland, England, and French Canada, didn’t come until the early 1850s. Next came the loggers, drawn by the vast swaths of old-growth forest that surround the region on three sides (its eastern border is the lakeshore), and by the Chaudiere River, which has its source in Lac Megantic, then flows north 115 miles to end at the St. Lawrence. In 1884, when the Canadian Pacific Railroad began construction of the last leg of its rail line linking Montreal with the port of St. John–and chose the lake region as the link point of its two legs–the town was formally christened. The railroad has been its heartbeat ever since.

Yves’ father used to tell him stories, he says, about the war years, the early 1940s, when trainloads of Canadian soldiers, bound for Halifax and from there to the Western Front, would come through Lac-Megantic on their way east: “It was their last stop before the U.S. border. They’d get off and party all night, then leave again in the morning. There were five or six hotels here–it was a big, happy town in those days.”

The last passenger train stopped here 20 years ago–but the freight traffic increased almost yearly: lumber and farm products, pulp and paper, local granite. Factories grew around the sawmills and quarries; today, on the north edge of town, an industrial park houses a door manufacturer, a furniture maker (where Yves has worked for 35 years), and a maker of particleboard, and employs nearly a fifth of the town’s population.

The region prospered modestly, with Lac-Megantic always its hub. Over time, a natural division took place: the southern bank of the Chaudiere, anchored by the parish of Notre-Dame-de-Fatima, became home to the town’s working class–its factory workers, loggers, and jobbers–while on the north bank, the business owners, store clerks, teachers, and bank tellers built their lives around l’eglise de Sainte-Agnes.

But for all that, it was a small town: 2,600 people at the close of the 19th century, still fewer than 6,000 today. Its growth was slow, its hardships were shared; and even between the two shores, from the earliest days there was the sense of a common lot.

“You have to understand how it is with us here,” says Gilles Blouin, a local native who heads the region’s genealogical society and claims as many as “30, 40, 50 cousins” in the area. “I may not know Jacques, but I know Jacques’ parents, or I know his grandparents, and probably some of his cousins. So in that way I know him, and I honor him. We all of us here, we stem out of the same few peasants.”

—

Driving southeast out of Nantes along Quebec Route 161, you follow the railroad tracks through six miles of scrub forest. The road is flat–or seems so–and mostly unbending. There are no houses to be seen, and rarely any cars; here and there a narrow dirt side road will curve off into the pines. Every mile or so, a disused boxcar, ancient-looking and smeared with graffiti, will appear to your right on a rusty strip of siding.

Then you pass through a crossroads and things begin to change. A U-Haul place. Then a gas station. A garden center, a body shop, a car dealer. The road widens, the cars increase, there are stoplights now and side streets: a Walmart, a hospital, a motel, a McDonald’s; a cemetery (Yves’ family’s resting place), its front row of gravestones only feet from the roadside on your right. The road has become a strip now–but not for long, and just as quickly it changes and narrows again: The stores become smaller, more modest, spaced more widely, as though the planners had somehow changed their minds in the middle.

Near the end of it all, on your left, its pair of Gothic spires dwarfing everything in sight–nearly everything in town–is l’eglise de Saint-Agnes, 100 years old last year.

You’ve been traveling rue Laval, the road into Lac-Megantic, running southeast along the lakeshore toward the river. A quarter-mile before it gets there, it bends ever so slightly to the south; this is rue Frontenac, which will take you two more blocks to the river. These last two blocks just past Sainte-Agnes, this quarter-mile just before the river meets the lakefront, is the core of the old city. And as anyone here will tell you, it is still the city’s heart.

It was here that you came, from Nantes or Lac-Drolet or Stornoway or any of a dozen other villages, long before the city spread north to the strip you drive in on today, to buy your tools or your groceries, check out a book, or listen to music. The library never left here, nor the local bank. Small restaurants and specialty stores–a bistro, several cafes, a chocolate shop, an antiques store, a lingerie boutique–replaced the businesses that moved to the strip, filling the storefronts of the century-old red-brick buildings that lined both sides of the street. The Musi-Cafe was one of these–by most accounts rue Frontenac’s most desirable destination–with its polished-oak bar and palm-ceilinged outdoor terrace. On the sidewalk outside, each and every cement square was centered in decorative granite. The gaslight-style streetlamps sat atop raised planters, each one spilling flowers.

One morning early last summer, Yves remembers, he was sitting in his car, stopped at the railroad crossing at the head of rue Frontenac, waiting for a train to pass: “And I was just looking out the window, at the street, at all of it–the flowers under the streetlights, the potted palm trees on the porch of the Musi-Cafe–and thinking how nice it all was. So clean and good to look at. Just really nice. It made me proud.”

—

No one saw the train begin its slow roll on the track in Nantes. It was dark–almost moonless–there was no one around, and as slowly as it must have been moving, it wouldn’t have made much noise. The first reliable sighting might have been by two teenagers, Alex Gagnon and Daniel Sivret, who were buying gas near the crossroads at the head of rue Laval in Lac-Megantic, two-thirds of a mile from the downtown, when the train passed just north of them.

“It was going too fast,” Alex would say several days later, “and there was no fire underneath, nothing to show that the brakes were on. I said to Daniel, ‘Imagine if it derails?'”

The track from Nantes to Lac-Megantic, like the road that runs alongside it, is mostly straight. The first turn comes just inside the crossroads entering the city, about where the two boys made their sighting–and the train cleared that turn. The next is a little sharper, just at the head of rue Frontenac, where the track veers east, away from the road. The train at that point, according to later estimates, was traveling between 60 and 70 miles an hour, roughly six times the speed limit. It was 1:14 a.m.

Some people talk about the noise. Others remember the smell, or the way the ground shook, or how the whole world turned orange–“brighter than the middle of the day, a blinding orange”–then black. Some people say they were paralyzed; others can recall only running. Some people say there was screaming; others say no, that no one screamed at all.

One man in town, an attorney named Robert Giguere, remembered later that he used to worry sometimes, even before it happened: “But then I would say to my wife, ‘No, we’re safe here. We live in a town where the trains can’t just race through, where they have to stop at a station.’ Who would have thought–a train without lights, without a driver, in the middle of the night?”

There were likely about 25 people still inside the Musi-Cafe, and another 15 or 20 on the terrace outside, when the five front locomotives plowed into the turn, making it halfway around, and then left the track, pulling free from the cars behind them. (They would be found later, still intact, a half-mile east.) Those on the terrace, many of them there for a smoke between sets, saw it happen: “A black blob that came out of nowhere, no lights, no signals, moving at a hellish speed,” one man would remember. They began running. Inside the bar, there was a trembling. Gaetan Lafontaine’s older brother, Christian, took his wife by the arm and muscled her outside. Gaetan was headed the other way, deeper into the bar, to find his wife, Joanie; their bodies would later be found together. The lights went out. The front windows turned orange. Somebody yelled “Fire!” Genevieve Breton, the young singer, at the bar with her boyfriend to buy a bottle of water for the walk home, turned with him and ran, but lost hold of his hand somewhere in the darkness.

One by one, the tanker cars derailed. Several of them ruptured, then exploded, sending a river of molten oil through the streets. A wall of fire went up, 100 feet high, as the derailed cars piled into one another, forming a three-story mountain of steel. The Musi-Cafe was engulfed. Those still inside, and others escaping too late, died instantly. (“Vaporized” was the word the coroners would use.) The temperature reached 3,000 degrees.

“The entire town was on fire to my right,” Yvon Ricard, the musician, who had been among the smokers on the terrace, would tell reporters later. “There was this big mushroom cloud … Wires were falling, transformers were exploding … We were running around houses, through backyards; we stopped running when we couldn’t feel the heat on our backs.”

There are a hundred stories of that night like this: of horror, near-death, and crazy, panicked flight. They are told by the survivors, about what they witnessed and how they survived, sometimes about someone who was with them, someone they might have loved who is gone. But these are only half the stories, and the others are less often told.

Of those who went to the Musi-Cafe that night, probably 26 or 27 (the exact number is hard to know) never came home. They were laborers, secretaries, business owners, waitresses, teachers, coaches, musicians, and the parents of at least 14 children. The youngest was 18; the oldest 52.

But Marie-France Boulet died that night, too, in the bedroom of her home on rue Frontenac; she was 62. And Talitha Coumi-Begnoche, 30, along with her two daughters, Bianka and Alyssa, ages 9 and 4. (“I would have preferred dying with them,” their father would say later.) And Roger Paquet, 61, who worked in the wood-pellet plant in town and lived alone on the lakeshore two blocks from the tracks. And 19-year-old Frederic Boutin, in an apartment across the street. And a 93-year-old widow, a retired bookkeeper and his wife, a couple in their twenties, an accounting student and a food worker who lived in apartments above the Musi-Cafe, and seven or eight others.

All dead in their homes when the one and a half million gallons of molten oil swept through the downtown like a tsunami. There were probably 20 of them, in addition to the other 27: 47 in all. The funerals would go on for three months.

—

I arrived for the first time in Lac-Megantic two months later, the Wednesday after Labor Day. For weeks I’d been reading the stories: hundreds of stories from scores of news sources. Every day brought more. In the first wave were the victims’ tales: the families’ anguish, the orphaned children, the death toll rising by the day. (It would be July 19, 13 days after the derailment, before the number stopped at 47.) Then came the chronicling of the physical losses: businesses, historic buildings, the library with its books and family archives, the downtown under a blanket of oil. And, from the first day to the last, the stories of human kindness: letters, dollars, clothes, toys, books; a benefit concert and plans for a fundraiser in sister city Farmington, Maine; a message from the queen; the flags at half-mast, for a week, on every government building in Quebec.

But the biggest single group of stories, once the first days had passed, were the stories of the trains. Many of the earliest ones involved the engineer, Tom Harding, and whether he’d set enough hand brakes. Next came the ones about Ed Burkhardt, CEO of MM&A’s parent company at the time, Rail World: how he’d arrived in town with a police escort four days after the derailment and been jeered by residents. There were stories about MM&A’s safety record–which by most accounts was frighteningly bad–about the condition of its tracks and its rules allowing one-man crews and oil-laden trains to be left unattended overnight. There were stories about oil trains in general and the hazards of their unchecked growth. “A massive, reckless increase,” wrote one columnist for The Guardian. He called the crash site “a corporate crime scene.”

Finally, and once they started, almost unendingly (and still today with no end in sight), there were the stories of the lawsuits. By the time I arrived in Lac-Megantic in September, I’d learned of a dozen or more: against MM&A; against Rail World; against Canadian Pacific, which had contracted with it to ship the oil; against Irving Oil, Western Petroleum, the Union Tank Car Company, several North Dakota oil companies. There have been dozens more since. Some are class-action suits, some countersuits; some were filed in Canada, others in the U.S. The amounts total hundreds of millions of dollars. They’ll be going on for years.

My first stop was at the McDonald’s on Laval, the strip on the way into town. Nearly every table was filled, mostly with families, sometimes three generations. Small children chattered underfoot; adults talked between tables, loudly, familiarly, all of it in French.

From there I drove south on Laval, three-quarters of a mile, until I came to the barricades. All vestiges of the old downtown had been erased, were still being erased. What had been rue Frontenac–the town’s library, post office, grocery store, a discount store, a hairdresser, a funeral home, several dozen offices, shops and apartments, as well as its three or four best restaurants–was now a quarter-mile wasteland of worked-over earth, twisted railcars, and human remains, cordoned off behind crime-scene tape and wire fencing, with police at either end. Huge backhoes plowed through four-story mountains of scorched dirt, as trucks carried off load after load. As far away as rue Champlain, 1,000 feet from the tracks, the paint on the houses was blistered and falling away. It was as though a bomb had been dropped.

I looked for the sign I’d read about in the papers, handwritten in block letters, posted alongside the tracks just outside the exclusion zone: You–The Train of Hell. Don’t Come Back Here. You’re Not Welcome Anymore. But someone had removed it.

There was to be a meeting that evening. Billed as a “public information session for the people of Lac-Megantic,” it was intended, the announcement said, to present the planners’ vision for “the creation of a new commercial hub.” I’d arranged for a translator, who turned out to be Yves. We’d never met before.

The meeting room, a makeshift auditorium inside the city’s two-year-old, $29 million, warehouse-like Sports Center, 500 feet from the wreckage site, was packed. On a raised stage in front sat the mayor–a former schoolteacher named Colette Roy-Laroche–and three or four provincial politicians and consultants whose names and titles I never learned. Behind them was a six-foot-high display of maps and colored diagrams: streets, roads, footpaths, parkland, and local landmarks, seemingly all of it divided into “green zones” and “blue zones.” Several of the officials addressed the crowd. The old downtown, they said, had been too contaminated by oil, which had fouled the soil in every direction, to be any longer usable. The oil would be pumped out wherever possible, but that would take time. Meanwhile, the downtown would be relocated, much of it to the river’s south shore, the neighborhood known as Fatima. There would be a bike path and gardens; part of the old downtown would be refashioned as a memorial park. All this, the mayor said, would serve to get businesses back on their feet, “unify the city,” “commemorate the dead,” and “integrate the story of the catastrophe for future generations.” Sixteen million dollars was available for the job, with more expected to follow.

The crowd was polite but plainly unhappy. A man whose brother had died in the fire rose to complain that the state’s coroner was still holding his body: “And now you tell me that the site of his house will be buried under a park.” It wasn’t right, he said. A red-haired woman said that she’d moved here years ago from Montreal because she liked the feel of a small town: “And now you’re talking about making us into something we’re not. I say no, no–please, sirs, keep us small!” The crowd applauded loudly.

On the way out with Yves, I asked him what he thought: Did he like the new plans, or did he agree with the red-haired woman? Oh, he said, it didn’t matter what he thought: “They’ll do what they want with it–and in the end it will look like the sports center, ugly and gray, like a factory. The town will survive, but for us who grew up here, who grew up with the old buildings, it will never be the same.”

—

There is almost no one in the region, it seems, who hasn’t been touched. I asked Yves whether he’d lost anyone. No, he said, not personally–but his niece’s best friend, whose birthday party he’d just attended, was among those who died in the Musi-Cafe, as was a co-worker, Yves Boulet. Henriette Latulippe, who’d died in her apartment next door, was the sister of a neighbor. “One way or another, I guess I knew maybe 10 of them,” he said.

“If you see somebody [on the street], well, first off you know it wasn’t them,” a local woman told a reporter after the deaths. “So then you ask, ‘How’s the family?’ And if they can talk, you know the family [is safe]. And then you say, ‘And everybody else?’ And that’s when you hear, ‘My son’s girlfriend, my cousin, my niece …'”

Photo Credit : Dario Ayala/The Gazette

Father Steve Lemay is the presiding priest at l’eglise de Sainte-Agnes. We met in mid-September at his office in the church rectory on rue Laval, 500 feet north of the derailment site. He spoke softly, in halting English. The background growl of heavy machinery would occasionally intrude.

He had just completed his 20th funeral, he said. There were 27 more still to come, with the remains of these last victims–often no more than a bone fragment or single tooth–still being held by the government coroner, awaiting identification. It was a heartbreaking process to witness, he said: “But for some people, it is hard to complete the grieving without something [tangible]. And they are willing to wait.”

He told me about how he had gone to the hospital early that first morning to give comfort to any injured survivors: “But no one was there, and after a time I understood that there would be no one [coming].” So he went instead to the high school, where the people were already gathering. There were many families there, he said, and many old people. But the hardest to witness were the mothers and fathers who couldn’t find their children.

“And they would come up to you with family photographs: ‘Avez-vous vu mon fils?’ they would say. ‘Avez-vous vu ma fille?’ And there would be nothing you could answer.”

Later that day, he said, there began to be lists: “Lists of the lost, lists of the living–and people would look at them, and know. That was very hard. To see such pain. I was praying for myself, praying for all of us.”

He feared the coming winter, he said: “It will be very hard. Winter is always hard here, the dark and the cold, and we are many miles away–but this one will be harder. We have to learn to be by ourselves, to remember that we are connected, that we are together. In that way we will help each other … That is the only solution to tragedy. God is present in the things we do to help each other. It is the only way.”

Two days after we met, on September 21, Father Lemay would preside at the funeral of Marie-France Boulet. Another local with a century-long family history in the town–one of 11 siblings, nearly all of them still here–she had died in her home, behind the lingerie shop she owned on rue Frontenac. The searchers had found nothing to identify her, only some charred gold pieces that had once been earrings and the half-melted remains of a souvenir spoon, which the authorities handed over to her family in a Ziploc bag. But she’d been gone almost three months by then; they’d decided to go ahead with the funeral.

I’d eaten dinner with her sister Paule, as well as Paule’s husband, Jacques Fortier (who served as translator) and her niece Alexe, several days before at a restaurant on rue Laval. I’d phoned her after reading a letter she’d written to the local weekly–“The right to information and the right to speak!” they’d headed it–in response to what would become known as Bill 57, an act of the provincial legislature giving the city sweeping powers in rebuilding, including the right to expropriate any home or business in the Fatima neighborhood on the river’s southern bank, at a price determined by formula, to make room for the new downtown.

The concern of the city’s leaders, at least as I understood it, was that if the rebuilding didn’t begin right away and progress at lightning speed, the accumulation of lost dollars in the downtown, coupled with the physical devastation and the jobs lost at the businesses that had been destroyed or shut down, could result in a mass exodus that would cripple the city for decades. Although I never met anyone willing to dispute this concern on its merits, almost no one seemed able to live with its result: that Bill 57, which would pass in its final form the day after my dinner with Paule, would reverse a century of culture and demography, that it would do so more or less by fiat, and would do it overnight.

Paule’s letter, in which she had pleaded that her neighbors not cede the town’s future to a “group of clever people with drawing boards,” was an impassioned piece of writing: wounded, uncrafted, almost a written cry; I was anxious to meet its author.

She was cautious at first, polite but only barely acknowledging me as she directed her words, always in French, toward her husband. It went this way for the first half-hour or so, the two of them talking mostly to each other, but always in answer to my questions: first about that July night and early morning, how they’d dropped Marie-France off at her house around 10:15 after returning from a family event, then been awakened at 2:00 a.m., “the sky bright as morning,” by Jacques’ son banging on the door; then about the family’s night-long vigil at another sister’s house as news came in and worry turned quickly to despair; and finally about the pain of having nothing of her sister, “not even a tooth,” to bury or say goodbye to.

“We are not alone, of course,” Jacques said at one point, almost as if to apologize. “In so many families today, in so many homes, there is pain.”

“It is true,” Paule’s niece said now, surprising us all. She was young, about 20, and had barely spoken up to this point. “For the first month after it happened, everybody cried,” she said now quietly, in perfect English, looking at me across the table. “It was all they did. They just watched the news and they cried.”

When the talk turned at last to the subject of her letter–the city’s seeming indifference to its people–Paule’s tentativeness was suddenly gone. She is fiftyish, dark-haired and pretty, and when she gets emotional her voice grows quicker and her green eyes seem sometimes on the edge of tears.

“Who is deciding these things?” she was asking of us suddenly, referring now to the architects of the city’s new plan. “Where do they live, these people who tell us where to work and where to live, who tell us what to do with our town? In Montreal? In Ottawa? Who are they? How can they say this to us, or to the people of Fatima: ‘Move your town, forget what is past’? ‘Here, we give you money, now go away’? How can you ask a people to forget their history?”

It was something I’d been hearing a lot in the week just past. I’d heard it from Yves, who was clearly saddened by it, even angry at certain moments, but in the end seemed more resigned than anything else. “I’m not really a fighter,” he had told me one day over lunch. “So my opinion isn’t going to matter very much in the end.” I’d heard it from a 68-year-old retired poll worker named Louis-Serge Parent, who compared it to the rebuilding of postwar Berlin: “The politicians in the end, they’re always going to take over. It all happens behind the scenes …” And I’d heard it, maybe most succinctly, from a reporter for the local weekly, Claudia Collard, who simply registered its sadness: “It’s too big, what’s happened to them–too big to even think about. First they lost their people; now they’re losing their town.”

But no one I’d met seemed more personally afflicted than Paule. “The town is my earth,” she told me now. “It is where I was born, it is where I have lived my life–and now they tell us to move it. No! I would rather they lay down a big slab of concrete [in the old downtown] and let us live our lives there, do our business there, and leave the people in Fatima alone … This thing they are doing, I cannot imagine it. The town I was born in, where my sister died, where all these people died, a big gray hole without life.”

—

I returned three months later, a week before Christmas. It was cold now, below zero both days I was there. The city seemed empty: the locals indoors, the roads mostly carless, the gawkers and reporters long departed from downtown. At the wreckage site, now under half a foot of snow, the workers toiled on, but the work was different from before. Much of the ground had been leveled, the wrecked tanker cars and old dirt carried off; newly poured concrete risers marked the contours of future streets, heading southeast off what remained of rue Frontenac toward the river and, once across, to what will be the new downtown.

On the northern riverbank, in what used to be a part of the Sports Center’s parking lot, its beginnings were already in place. Four modular concrete buildings, to house a liquor store and other tenants still to be announced, were largely complete: the core of what will be a 45,000-square-foot strip mall. Across the river in Fatima, in the snow in front of the now-shuttered l’eglise Notre-Dame-de-Fatima–which after 67 years had celebrated its last Mass in September–a sign informed passersby that the site would soon be the home of the city’s new supermarket.

But there was grace, too, to be seen–even what might be called hope. In the snow along the triangle of land at the foot of l’eglise de Sainte-Agnes, a small forest of lighted Christmas balsams, one for each victim (including a 48th for the volunteer firefighter who had taken his own life shortly after), most with photos or other mementos in their branches, tapered gradually downhill toward the river. Donated by a local tree farmer, they’d been planted in irregular rows, then lit together by the families three weeks before Christmas in a ceremony after evening Mass. Seeing them there, their lights shimmering like colored fireflies at the base of rue Laval–a stone’s throw from where those they remember had died–I couldn’t help but be reminded of what Gilles Blouin, the local genealogist with “50 cousins,” had said to me three months before: “We will come out of this closer, I think. It has happened already, I have seen it. The sorrow of losing someone loved–a brother, a son–today reunites a family that was estranged, that had hardly talked in years. Shared loss can be powerful that way.”

I met with Yves my second morning in town. Nothing much had changed, he told me; nearly everything they’d announced at the town meeting in September was coming to pass. He seemed despondent. I said so, and asked him why. He talked for a few minutes about the coming of winter, then about the new buildings going up in Fatima: “Just metal and concrete, it’s so impersonal.”

He grew quiet before he spoke again. “The town is gone,” he said. “It was gone the morning of July 6th, no matter what they do.”

That night, my last in Lac-Megantic, I had dinner with Paule and Jacques at a small restaurant across the street from Sainte-Agnes. Both seemed more subdued than I remembered. At some point, mostly to make conversation, I asked Paule whether she’d written any more letters to the paper since we’d met. She shook her head no. I asked whether she thought she would. Jacques translated the question. She shook her head again, more vigorously this time. For a moment I thought I had upset her.

“I have stopped writing,” she said. “I have stopped talking. I just want to go.”

I was confused. Jacques clarified: She meant that she wanted to leave the city. She wanted to move away.I asked why. Where would she go? Jacques passed on her response: “This is not the city where I was born. My earth is not here anymore.” She seemed about to cry.

She excused herself then, and Jacques and I were alone. He had tried to talk to his wife, he told me; her family had tried as well: “Her brother tells her she’s just running away from things, that that can’t be the answer.” But none of it was getting through, he said: “Her whole family is here. Her friends, her whole life. But she says she wants to leave. For me, I love it here, the people, the lakes, the big mountains. But she wants to go. I don’t know. I don’t know what to say anymore.”

It was close to 9 o’clock. Outside, in a lightly falling snow, we stood in the doorway of the restaurant, drawing out our goodbyes. Across the street in front of Sainte-Agnes, the twinkle from the 48 clusters of tree lights cast a bluish glow. I would be leaving in the morning. I said again how sorry I was for their loss and that I hoped the new year would be brighter. I shook their hands and turned to go. Paule pulled lightly on my sleeve: “Please, come see my sister’s tree.”

We walked together across the street, then climbed the slight grade onto the snowfield where the cluster of trees had been planted. Crude footpaths in the snow, some more well-trodden than others, crisscrossed around and among them. Marie-France’s tree was near the center. For a minute or so we stood around it, none of us speaking, as Paule dusted the snow off its upper branches, removed a small photo, caressed its glass briefly, then returned it to its place.

Geoffrey Douglas is the author of four books of nonfiction and is currently at work on his first novel.