Remembering December 1941

A 1941 Keene, New Hampshire newspaper provides a glimpse into the early days of WWII. Life in America would never be the same.

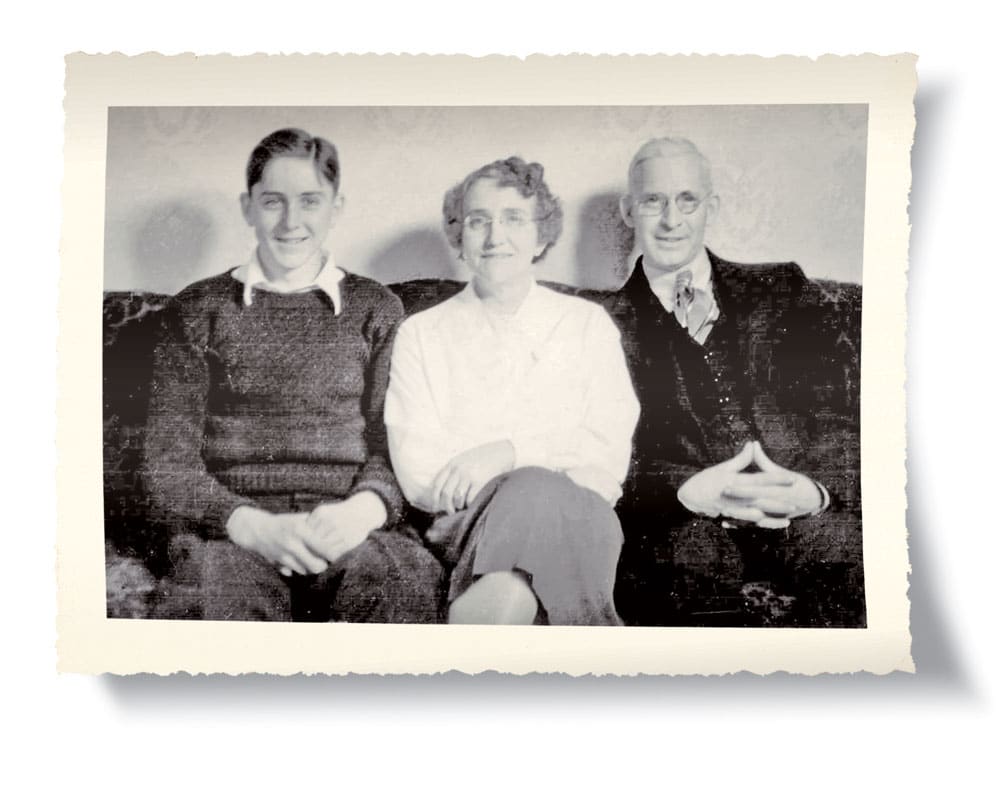

Edwin Hopkins (left)—the first soldier from Keene to lose his life in World War II—at home with his parents Frank and Alice in the late 1930s.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Tom Gray (Hopkins)

December 1, 1941, was the coldest day of the autumn in New England. It was five below zero in northern Maine and 12 degrees above in Keene, a city of about 14,000 in Cheshire County, New Hampshire.

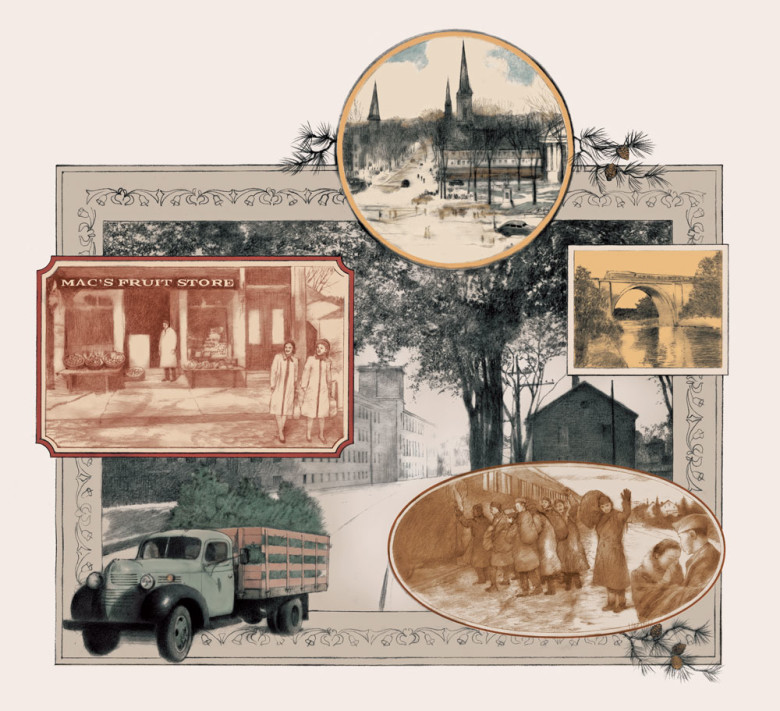

“It seems good to see the little Christmas trees up on the lampposts around the center of the city,” wrote Henry Davis Nadig, a columnist for the Keene Evening Sentinel who styled himself “The Cheshire Cat.” “It won’t be long now before nightly we shall be offering a very cheery appearance to the winter visitor coming into Keene.”

At that time, the Sentinel, founded in 1799, was the seventh-oldest daily paper in America, and the oldest to be continuously owned by the same family. Five full-time reporters, two editors, and 22 local correspondents covered the city and its surrounding towns, printing 4,800 copies every afternoon.

Although America was not yet at war, war dominated the news: “Japanese Cabinet Decides to Continue Negotiations, U.S. Philippine Forces Ready” blared the Sentinel’s front page that day. The state office of the Selective Service had been ordered to begin physical exams of draft-eligible young men, and Brig. Gen. Charles Bowen warned that conscientious objectors must base their refusal to serve on religious belief, not “political concepts.” A smaller story at the bottom of the front page noted that the Australian government had warned that a break in relations between the U.S. and Japan “might come at any moment.”

But due attention was paid to ordinary life as well. Mac’s Fruit Store was advertising large Florida oranges for 29 cents a dozen, and steaks were selling for 31 cents a pound at the First National supermarket. There were Christmas sales on everything from holiday cards to storm windows.

Keene High opened its basketball season with a bang, smashing Thayer 42-8. Mr. and Mrs. Jeremiah Driscoll of 21 Richardson Court celebrated their 40th anniversary, and 14-year-old Clifton Chambers Jr. of Surry shot a 135-pound spike horn buck, though it had been a poor hunting season—too warm and not enough snow for tracking. Nevertheless, the Sentinel had some fun with a story about “a deer-colored goat” that was bagged in Swanzey.

“The Cheshire Cat” reported that mild temperatures had made the city “the foggiest I’ve ever seen. Couldn’t even see the lights glowing from Central Square as I came up past the Scenic Theatre,” he wrote, where Sergeant York, the World War I epic starring Gary Cooper, was to open the next day, Sunday, December 7.

Photo Credit : Courtesy Keene Public Library

The Keene area got first word of that day’s attack on Pearl Harbor from the new radio station in town, WKNE. The Sentinel posted the news on a bulletin board outside its office on St. James Street, and it wasn’t until the afternoon of December 8 that banner headlines appeared on the front page: “U.S. Declares War on Japan. Jap Planes Attack Pearl Harbor. Death Toll of 1500.” The next morning, eight young Keene men were in line at the recruiting office when it opened.

More than 20 local men were already serving in Hawaii, and details of the tragedy trickled in for weeks. On December 21, the Hopkins family of North Swanzey got a telegram from the War Department telling them their 19-year-old son Edwin, a Navy fireman third class on board the USS Oklahoma, was missing in action. It was not until February 18, 1942, that Eddie’s death was officially declared. He was Keene’s first lost boy, and in 1943 the city named its new municipal airport Dillant-Hopkins field for him and Lt. Thomas Dillant, an Army Air Corps pilot from Keene who died in a training accident.

Reaction to the war was not always reassuring. To guard against sabotage, all employees at Perkins Machine Company were fingerprinted, and a Sentinel editorial urged “no Japanese light bulbs, no Japanese toys, no Japanese combs and brushes be purchased by its readers.”

Residents buried their fear and grief in war-related work. By Thursday, December 11, 100 volunteer air raid wardens had started training and 39 people had signed up for a seven-week first-aid course at the YMCA. Even local advertising took on a martial tone. “Your weekly food order plays an important part in the defense of your home,” declared a grocery store offering pork roast at 19 cents a pound.

Despite the new reality, the celebration of Christmas went on. The Keene Hairdressers Association sponsored a Dance for Defense featuring the legendary square dance caller Ralph Page to benefit the servicemen and women of Keene. Keene Teachers College put on a Christmas Cantata before 500 music lovers at Spaulding Gymnasium, and Keene High School’s a cappella choir presented their most beautiful concert ever, according to the “Cheshire Cat,” who added that holiday music was essential for “relaxation and spiritual uplift,” as well as to “give reassurance to youth in these tense times.”

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Tom Gray (Hopkins)

Sermons at city churches on December 14 were predictably patriotic, although at the Unitarian Church, Rev. W. W. Lewis reminded his congregation that “the conscientious objector has the right to his position the same as you,” adding that “the time is now to save ourselves from the paganism of hatred.”

Community leaders scheduled a Carol Sing in Central Square for Christmas Eve. A cold rain typical of that winter dampened the enthusiasm, though, and the turnout was disappointing. It was perhaps the lowest moment of the lowest month of the year. The war news continued gloomy, with the Japanese advancing all over the Asian front. The British bastions of Hong Kong and Singapore fell, and on December 24, U.S. forces withdrew from Manila, leaving it to the invaders. Even the weather, the picturesque snow of a New England winter, was missing in action.

The Sentinel’s Nadig strained for a hopeful note. “We are fighting, we know, on God’s side, and therefore, no matter how black and how apparently discouraging may be the material evidence of the very present, the great and enduring forces of good will be victorious,” he wrote. “The Star of Bethlehem still shines, and it is the large and ever-present hope of millions of people all over the world.”

The concert was scheduled to end at 10 p.m., but a few drenched diehards stayed around to sing an impromptu version of “America” before drifting home. As they did, the rain petered out, and the skies began to clear.