History

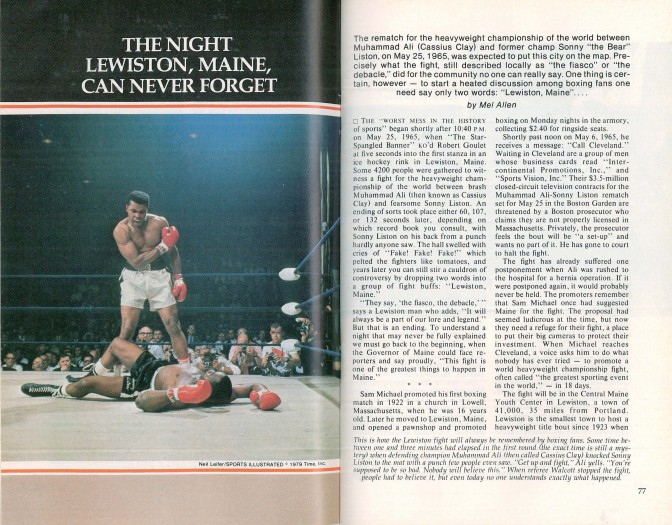

Ali vs. Liston | The Night Lewiston, Maine, Can Never Forget

The May 25, 1965, Ali vs. Liston fight for heavyweight champion of the world was supposed to make Lewiston, Maine, famous. Instead, it became “the fiasco.” Excerpt from “The Night Lewiston, Maine, Can Never Forget,” Yankee Magazine, May, 1979. The rematch for the heavyweight championship of the world between Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay) and former […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanThe May 25, 1965, Ali vs. Liston fight for heavyweight champion of the world was supposed to make Lewiston, Maine, famous. Instead, it became “the fiasco.”

Excerpt from “The Night Lewiston, Maine, Can Never Forget,” Yankee Magazine, May, 1979. The rematch for the heavyweight championship of the world between Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay) and former champ Sonny “the Bear” Liston, on May 25, 1965, was expected to put this city on the map. Precisely what the fight, still described locally as “the fiasco” or “the debacle,” did for the community no one can really say. One thing is certain, however – to start a heated discussion among boxing fans one need say only two words: “Lewiston, Maine.” . . .

The “worst mess in the history of sports” began shortly after 10:40 PM on May 25, 1965, when “The Star-Spangled Banner” KO’ d Robert Goulet at five seconds into the first stanza in an ice hockey rink in Lewiston, Maine. Some 4200 people were gathered to witness a fight for the heavyweight championship of the world between brash Muhammad Ali (then known as Cassius Clay) and fearsome Sonny Liston. An ending of sorts took place either 60, 107, or 132 seconds later, depending on which record book you consult, with Sonny Liston on his back from a punch hardly anyone saw. The hall swelled with cries of ” Fake! Fake! Fake!” which pelted the fighters like tomatoes, and years later you can still stir a cauldron of controversy by dropping two words into a group of fight buffs: ” Lewiston, Maine.”

“They say, ‘the fiasco, the debacle,’ ” says a Lewiston man who adds, “It will always be a part of our lore and legend.” But that is an ending. To understand a night that may never be fully explained we must go back to the beginning, when the Governor of Maine could face reporters and say proudly, “This fight is one of the greatest things to happen in Maine.”

Sam Michael promoted his first boxing match in 1922 in a church in Lowell, Massachusetts, when he was 16 years old. Later he moved to Lewiston, Maine, and opened a pawnshop and promoted boxing on Monday nights in the armory, collecting $2.40 for ringside seats.

Shortly past noon on May 6, 1965, he receives a message: “Call Cleveland.” Waiting in Cleveland are a group of men whose business cards read “Intercontinental Promotions, Inc.,” and “Sports Vision, Inc.” Their $3 .5- million closed-circuit television contracts for the Muhammad Ali-Sonny Liston rematch set for May 25 in the Boston Garden are threatened by a Boston prosecutor who claims they are not properly licensed in Massachusetts. Privately, the prosecutor feels the bout will be “a set-up” and wants no part of it. He has gone to court to halt the fight.

The fight has already suffered one postponement when Ali was rushed to the hospital for a hernia operation. If it were postponed again, it would probably never be held. The promoters remember that Sam Michael once had suggested Maine for the fight. The proposal had seemed ludicrous at the time, but now they need a refuge for their fight, a place to put their big cameras to protect their investment. When Michael reaches Cleveland, a voice asks him to do what nobody has ever tried — to promote a world heavyweight championship fight, often called “the greatest sporting event in the world,” — in 18 days.

The fight will be in the Central Maine Youth Center in Lewiston, a town of 41,000, 35 miles from Portland. Lewiston is the smallest town to host a heavyweight title bout since 1923 when the citizens of Shelby, Montana (pop. 3000), brought Jack Dempsey and Tom Gibbons together. (The people of Lewiston were 75 percent French-speaking. They worked in mills making shoes and bedspreads where the average weekly paycheck was $50.)

With only two hotels in Lewiston, the Poland Spring House, 12 miles away, houses the crush of 600 journalists — about the number which covered World War II — arriving for the fight. The famous but time-worn resort that once catered to the rich and famous looks to one writer, “as though the Kaiser would step out any second.”

In the lobby cigar ashes tip into $928 worth of souvenir ashtrays, compliments of the Maine tourist office. The broad-shouldered men who sit in the wicker chairs along the half-mile of veranda have names like Louis, Marciano, Walcott, Sharkey, and Patterson. But the real attraction is Sonny Liston, who has moved his training camp here from Dedham, Massachusetts.

The fists of Sonny Liston measure 15-1/2 inches. No ordinary boxing glove fits them and his must be custom-made. They are probably the largest fists in heavyweight history and have devastated the ranks: three of his last four fights ended in first-round knockouts. He is called “the ultimate weapon in unarmed combat.”

It was his last fight, though, 15 months ago in Miami, against the then-named Cassius Clay, that has put Liston in the unexpected role of challenger. Then, a fatigued and cut champion did not answer the bell for the seventh round, suffering, he said, from an injured left shoulder.” I took Clay too light before,” he tells reporters. “This time I’m gonna bring my lunch. We may be in there a long time.”

He lives in the Mansion House, a separate hotel built in 1796, amidst old-world elegance. He trains in the ballroom, and spars in a ring with chandeliers overhead and sunlight filtering through green stained glass.

He runs on the golf course in his familiar hooded sweatshirt. Once he surprises a greens keeper tending a water hazard who glances at the hooded spectre emerging suddenly from the mist — and topples into the pond.

Experts say they have never seen him train so hard. “He’s ready,” they say, and they discount that at 33 he gives away 10 years to Ali. Nobody is surprised when the odds-makers make him a solid favorite to regain his title. The doctor who examines Liston for the Maine Boxing Commission leaves the room in awe. “He’s the fittest man I’ve ever examined, ” he says.

But his sparring partners are worried. It is obvious to them he has left more than his championship on the stool in Miami. They reach him frequently with right-hand counter-punches as he lunges in, off-balance. They hope he has merely over-trained. When reporters ask for a prediction, though, they are fixed with the “hard brown eyes” ‘that people say knocked out Floyd Patterson before the left hook arrived.

“Don’t blink,” Liston growls, “or you’ll miss the knockout.”

Every night Muhammad Ali dreams the same dream. At the opening bell he rushes across the ring and shivers Liston with a right. Liston falls, a look of astonishment on his face. Standing over him, Ali shouts, “Rise and shine. Rise and shine.” When he awakens before dawn in his Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, training camp, trainer ‘Bundini Brown is shaking him. “Rise and shine, champ. Rise and shine.”

The dream is so real that Ali, uncharacteristically, says he has no prediction. “If I told you what would happen nobody would come,” he explains. He offers a poem, instead, and reporters can make of it what they will.

The fight was moved from Boston to Maine. Wherever the Bear goes he’ll end up in pain.

Liston the Bear said,” I was a big fool. This time I’m flat on my back instead of the stool.”

When the fight was over and the champ left town

Everyone for Liston wore a big frown.

In Ali’s camp is old-time comedian Stepin Fetchit. He sings and dances and keeps everybody “loose.” He also reportedly has taught the champion a secret punch. He calls it the “anchor punch” and says he learned it from the immortal Jack Johnson who told him to pass it on, when the right man came along. Nobody has heard of an “anchor punch” and attribute its appearance now to Ali’s usual bravado. “It’s my secret,” Ali insists. “You’ll believe it when you see it.”

Ali, at 23, is a stronger, better fighter than he was for the first Liston bout. He is supremely confident. “Last time I was ducking just to get away,” he explains. “This time I’m looking to set him up.” He tells the world, “The Secretary of the Interior should declare my face a natural resource,” and tells his manager, Angelo Dundee, he may hide a muleta in his boxing trunks and play Liston like a matador with his bull.

A week before the fight, however, a cloud appears that has little to do with Sonny Liston but which threatens to upset the fighters more than right-hand counters. There are police reports from New York that a red Cadillac carrying a Black Nationalist assassination squad is enroute to Maine to avenge the shooting of Malcolm X, a Black Nationalist who defected from the Black Muslims. Ali, the most prominent Muslim in America, is the likely target. A special police detail from New York slips quietly into Lewiston.

State police increase their security around Chicopee. When Ali runs in the morning he sees police hats poking from behind bushes along his route. “I’m too fast to be hit by a bullet,” Ali tells reporters, most of whom feel they assuredly are not. There are reports that bullet-proof shields have been ordered for the press section and the Boston Globe takes out extra insurance on five of its sportswriters. “I don’t want Lewiston to go down in history as the place where the heavyweight champion was killed,” says Lewiston police chief Joseph Farrand.

On his last day of workouts before leaving for a Holiday Inn near Lewiston where he will stay three days before the fight, Ali is leaning against the ropes sparring with his boyhood friend from Louisville, Jimmy Ellis. Ellis is a light heavyweight who six years later will meet Ali in the ring for keeps, but now he is trying to prepare Ali for Liston’s body blows. Ali is not at his best. He has argued with his wife, Sonji, who balks at the Muslim strictures: no makeup, no dancing, no short dresses. It is an argument that will persist until their divorce six months later. Ali is wondering what to do about her when suddenly Ellis crashes a right to his ribs.

In his room Ali lies down and rubs his side with wintergreen and alcohol. Even though he is known for his boxing and his speed rather than his punching power, he vows to go for a quick knockout. He cannot afford to let Liston hit the side. In their first fight, he remembers, Liston hurt him plenty with body punches. He thinks of the dream and considers this his sign that he must catch Liston unawares. He leaves Chicopee early the next morning. He has boasted he will” raid the Bear’s camp” and Saul Feldman has tied two black bears from the state game farm to posts outside the Poland Spring House in anticipation. Ali pulls up to the Holiday Inn in his brightly painted bus he calls “Big Red.” Even though he is three hours early, there are several hundred people waiting for him. He stands on the balcony and shouts: ” I am the savior of boxing. You’re looking at history’s greatest fighter. There will never be another like me.” Everyone laughs. Then Ali goes inside and lies down, holding his side. He has forgotten about raiding the Bear’s camp, and the black bears cough on their chains until darkness comes, and they are trucked back to the game farm.

Tuesday, fight day, is the biggest day in Lewiston since John Kennedy held a rally in the park in 1959. The crowd begins to gather at twilight, assembling on a hillside overlooking the Youth Center, armed with binoculars, looking for celebrities. Newly erected transmitting towers rise behind them, ready to beam the fight for the first time to Europe, Africa, and Russia. Western Union personnel, crammed into trailers in the parking lot, try frantically to keep pace with words, already half a million strong, more than for any fight before. UPI has grabbed the four fastest track men from local Bates College and has them primed to race down the smoky aisles into the night with round-by-round reports clutched in their hands.

Ali arrives at 9:15 in his bus. He enters by a rear door through a cordon of state policemen. Around him a security force of over 300 men, the largest ever for a sporting event, search pocketbooks for concealed weapons. Ali appears unconcerned. As he disappears down a corridor he is singing at the top of his voice, “Let’s Dance.” When Liston arrives he is dressed in blue jeans and a sweatshirt. He walks past the troopers saying nothing, staring straight ahead. Sam Michael sits five rows back from ringside. There is nothing left to do. He had constructed three rings before this last one, trucked at the last minute from Baltimore, satisfied Angelo Dundee who regards a ring as his fighter’s home for 15 rounds. It is obvious there will be no sell-out — in fact the 4200 announced attendance will be the lowest for a heavyweight title fight in modern times — but Michael is happy. Intercontinental has promised Michael the rematch should Liston win as expected. “If the fight is a corker, Lewiston will be the fight capital of the world,” he tells friends.

The referee is Jersey Joe Walcott. He is a former heavyweight champion who once was belted out in two minutes by Marciano with jeers of ” Fake! Fake!” ringing in his ears. He is a popular man with an infectious smile whose previous work as a referee in a title bout provoked controversy.

The knockdown timekeeper is Francis McDonough, a small, bespectacled 63-year-old retired printer who is tanned from a winter in Florida. His job is to count off the seconds a fallen fighter remains on the canvas, sweeping his arm up and down as the referee counts in unison. Since Maine rules stipulate only the referee can stop a fight, he is merely a beacon a point of reference by which to pick up the count. In a glaring oversight, Walcott never locates his knockdown timer before the fight. When the crucial moment arrives, he will look in vain for the small man barely visible over the ring apron.

The official timer is a 55-year-old high school teacher named Russell Carroll. He has timed fights for three decades. He was timekeeper at the world’s quickest fight — 10-1/2 seconds — that ended when AI Couture ran across the ring a split second before the bell and belted his opponent as he turned from his corner. Afterwards the rules were changed, so that record time will stand forever. There is no official clock hovering high above the crowd as in Madison Square Garden, so his stopwatch must supply the official time. This is the first time he will time a fight without his personal watch. His own watch does not have a reset button, that when pressed sets the time back to zero. The one provided by the boxing commission does.

In the locker room Bundini Brown smears vaseline into Ali ‘s shoulders, working it into the torso with vigorous strokes. Somebody leans into the room and shouts, “Ten minutes!” Bundini wipes the vaseline off with a towel. Ali takes a deep breath and walks to the rear of the locker room where he says his prayers.

Robert Goulet stands in the center of the ring, looking magnificent in a tuxedo, and offers prayers of his own: in a few minutes his rendition of the national anthem will be heard around the world, and he cannot remember the words. Somewhere between his car and this ring he has lost his palm notes. He was raised in Canada and “The Star-Spangled Banner” has always been a troublesome work. When he climbed into the ring reporters at ringside heard him mutter, “What am I going to do?”

That he cannot hear when the organ begins does not help. Only when technicians wave frantically at him to get going does Goulet realize that the organ is careening along on a solo. The song belts him immediately: “Oh! Say can you see by the dawn’s early night?” and bedevils him the rest of the agonizing way. (At another juncture ” fight” is substituted for “night.”) When he finishes, the first UPI trackster streaks away carrying this report: “The Clay Liston fight has begun and the following is a round-by-round report.” By the time he reaches the trailers, Western Union has a message for him. As Russell Carroll strikes the gong for round one, he is gripped with a sensation that “something is going to go wrong.”

Ali circles, holding his elbow close to his side. Liston moves cautiously, sluggishly, to meet him. Barely over a minute slides by with only minor skirmishing when suddenly Liston lunges from a crouch. His left foot is off the ground and he is off-balance. At that moment Ali bounces off the ropes and throws a right that travels eight inches before landing flush on Liston’s cheekbone with a downward twist. The blow snaps Liston’s head down at the same time it lifts his foot high off the canvas. Most people do not see the punch, only Liston’s collapse, as though a wind gust has tossed him to the ground.

Ali is hysterical. “Get up and fight. You’ re supposed to be so bad. Nobody will believe this,” he yells, standing over Liston. Walcott is afraid Ali will kick Liston and he tries to steer him to a neutral corner. But Ali is uncontrollable. Liston is not knocked out. But neither is he in. His is a misty world. Francis McDonough dutifully slaps his arm up and down on the table. At the count of eight, Liston is on one elbow, but Ali is glaring down, his fists ready, and Liston, who has not heard a referee ‘s count, slides back down.

By the time Walcott has pushed Ali back, McDonough’s count has reached 20, where he stops. Liston has fought grimly back from his mist, and as he finally stands he blinks in bewilderment as though emerging from a tunnel. Now Walcott assists Liston, holding him while he looks in panic around the ring apron for the knockdown timer. Not knowing what to do, he dusts off Liston’s gloves, and, as incredible as it seems, the fight continues.

This galvanizes Nat Fleischer into extraordinary actions. Fleischer is the grand old man of boxing, the feisty editor of Ring Magazine.

He runs to Russell Carroll, minding his stopwatch, and yells, ” Stop the match! The fight is over!” Carroll, flustered, presses the reset on his watch, without realizing it. He is not sure if the fight is on or off. Ali is hitting Liston again, so Carroll restarts his watch.

Fleischer turns to Walcott who wants somebody to get him out of a horrible mess.” Joe,” he screams, “the fight is over! ” Walcott turns away from the fighters. Liston is trying gamely to fight back and later one writer wondered, What would have happened if Liston had knocked Clay out while the referee consulted with Fleischer and McDonough? Walcott is convinced that Liston has been counted out.

When Walcott separates them and leads the challenger away Liston thinks the round is over. He thinks he was lucky to escape that one. He looks back and sees Ali’s arm raised by Walcott. Only then does he know the fight is over.

The fight establishes several dubious firsts. It is the first fight stopped by a magazine editor. It is also the first fight stopped without the referee’s counting one second over the fallen fighter. And it is the first fight to record “official” times of 1 minute, 1:47, and 2:12, the discrepancies due to Carroll’s inadvertent resetting of his watch, and to differences of opinion as to when the fight was actually over.

At 2 A.M. Liston serves coffee in the Mansion House, while his wife Geraldine cries softly in a corner. “Fourteen years is a long time,” she says. “I’m glad it’s over.” But Liston will fight again. He wins 16 straight in a comeback that ends when Leotis Martin knocks him out. His last fight is in a smoky little fight club in Jersey City on June 29, 1970. Six months later he dies in his home, alone. When he falls his fists evidently smash against a bench, for when he is found seven days later the bench lies in splinters by his head.

Ali is stung by the cries of “Fake” that fill the hall. “I hit him hard enough to knock out any man,” he says. “I told you I had a secret,” he adds. “That was my anchor punch. It’s lethal.” After the fight, Ali fights many times, but the anchor punch is not heard of again.

Only a handful of reporters actually saw the punch. Those that did were convinced of its power. However charges of “fix” filled the papers for days. Jimmy Breslin called the fight “the worst mess in the history of sports.” Another writer added, ” It was boxing’s shot in the arm — embalming fluid.” Of all the Maine officials, Francis McDonough suffered the most. He said his job was to count over a fallen fighter, and that he did. He did not tell Walcott to stop the fight, only that Liston had been down for at least 20 seconds. He stopped speaking to reporters. When he died three years later, much of his obituary concerned his role in the ill-fated fight, a task that from 68 years of life consumed 20 seconds.

Lewiston today enjoys a certain pride in the fight. After all, how many people can name where Ali fought Zora Folley, say, or Cleveland Williams. But go anywhere where people are talking boxing and to start an argument you just say two words: “Lewiston, Maine.”

“It’s part of our lore and legend,” the man says, and for Lewiston, at least, the fight will never really be over.

The rematch for the heavyweight championship of the world between Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay) and former champ Sonny “the Bear” Liston, on May 25, 1965, was expected to put this city on the map. Precisely what the fight, still described locally as “the fiasco” or “the debacle,” did for the community no one can really say. One thing is certain, however – to start a heated discussion among boxing fans one need say only two words: “Lewiston, Maine.” . . .

The “worst mess in the history of sports” began shortly after 10:40 PM on May 25, 1965, when “The Star-Spangled Banner” KO’ d Robert Goulet at five seconds into the first stanza in an ice hockey rink in Lewiston, Maine. Some 4200 people were gathered to witness a fight for the heavyweight championship of the world between brash Muhammad Ali (then known as Cassius Clay) and fearsome Sonny Liston. An ending of sorts took place either 60, 107, or 132 seconds later, depending on which record book you consult, with Sonny Liston on his back from a punch hardly anyone saw. The hall swelled with cries of ” Fake! Fake! Fake!” which pelted the fighters like tomatoes, and years later you can still stir a cauldron of controversy by dropping two words into a group of fight buffs: ” Lewiston, Maine.”

“They say, ‘the fiasco, the debacle,’ ” says a Lewiston man who adds, “It will always be a part of our lore and legend.” But that is an ending. To understand a night that may never be fully explained we must go back to the beginning, when the Governor of Maine could face reporters and say proudly, “This fight is one of the greatest things to happen in Maine.”

Sam Michael promoted his first boxing match in 1922 in a church in Lowell, Massachusetts, when he was 16 years old. Later he moved to Lewiston, Maine, and opened a pawnshop and promoted boxing on Monday nights in the armory, collecting $2.40 for ringside seats.

Shortly past noon on May 6, 1965, he receives a message: “Call Cleveland.” Waiting in Cleveland are a group of men whose business cards read “Intercontinental Promotions, Inc.,” and “Sports Vision, Inc.” Their $3 .5- million closed-circuit television contracts for the Muhammad Ali-Sonny Liston rematch set for May 25 in the Boston Garden are threatened by a Boston prosecutor who claims they are not properly licensed in Massachusetts. Privately, the prosecutor feels the bout will be “a set-up” and wants no part of it. He has gone to court to halt the fight.

The fight has already suffered one postponement when Ali was rushed to the hospital for a hernia operation. If it were postponed again, it would probably never be held. The promoters remember that Sam Michael once had suggested Maine for the fight. The proposal had seemed ludicrous at the time, but now they need a refuge for their fight, a place to put their big cameras to protect their investment. When Michael reaches Cleveland, a voice asks him to do what nobody has ever tried — to promote a world heavyweight championship fight, often called “the greatest sporting event in the world,” — in 18 days.

The fight will be in the Central Maine Youth Center in Lewiston, a town of 41,000, 35 miles from Portland. Lewiston is the smallest town to host a heavyweight title bout since 1923 when the citizens of Shelby, Montana (pop. 3000), brought Jack Dempsey and Tom Gibbons together. (The people of Lewiston were 75 percent French-speaking. They worked in mills making shoes and bedspreads where the average weekly paycheck was $50.)

With only two hotels in Lewiston, the Poland Spring House, 12 miles away, houses the crush of 600 journalists — about the number which covered World War II — arriving for the fight. The famous but time-worn resort that once catered to the rich and famous looks to one writer, “as though the Kaiser would step out any second.”

In the lobby cigar ashes tip into $928 worth of souvenir ashtrays, compliments of the Maine tourist office. The broad-shouldered men who sit in the wicker chairs along the half-mile of veranda have names like Louis, Marciano, Walcott, Sharkey, and Patterson. But the real attraction is Sonny Liston, who has moved his training camp here from Dedham, Massachusetts.

The fists of Sonny Liston measure 15-1/2 inches. No ordinary boxing glove fits them and his must be custom-made. They are probably the largest fists in heavyweight history and have devastated the ranks: three of his last four fights ended in first-round knockouts. He is called “the ultimate weapon in unarmed combat.”

It was his last fight, though, 15 months ago in Miami, against the then-named Cassius Clay, that has put Liston in the unexpected role of challenger. Then, a fatigued and cut champion did not answer the bell for the seventh round, suffering, he said, from an injured left shoulder.” I took Clay too light before,” he tells reporters. “This time I’m gonna bring my lunch. We may be in there a long time.”

He lives in the Mansion House, a separate hotel built in 1796, amidst old-world elegance. He trains in the ballroom, and spars in a ring with chandeliers overhead and sunlight filtering through green stained glass.

He runs on the golf course in his familiar hooded sweatshirt. Once he surprises a greens keeper tending a water hazard who glances at the hooded spectre emerging suddenly from the mist — and topples into the pond.

Experts say they have never seen him train so hard. “He’s ready,” they say, and they discount that at 33 he gives away 10 years to Ali. Nobody is surprised when the odds-makers make him a solid favorite to regain his title. The doctor who examines Liston for the Maine Boxing Commission leaves the room in awe. “He’s the fittest man I’ve ever examined, ” he says.

But his sparring partners are worried. It is obvious to them he has left more than his championship on the stool in Miami. They reach him frequently with right-hand counter-punches as he lunges in, off-balance. They hope he has merely over-trained. When reporters ask for a prediction, though, they are fixed with the “hard brown eyes” ‘that people say knocked out Floyd Patterson before the left hook arrived.

“Don’t blink,” Liston growls, “or you’ll miss the knockout.”

Every night Muhammad Ali dreams the same dream. At the opening bell he rushes across the ring and shivers Liston with a right. Liston falls, a look of astonishment on his face. Standing over him, Ali shouts, “Rise and shine. Rise and shine.” When he awakens before dawn in his Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, training camp, trainer ‘Bundini Brown is shaking him. “Rise and shine, champ. Rise and shine.”

The dream is so real that Ali, uncharacteristically, says he has no prediction. “If I told you what would happen nobody would come,” he explains. He offers a poem, instead, and reporters can make of it what they will.

The fight was moved from Boston to Maine. Wherever the Bear goes he’ll end up in pain.

Liston the Bear said,” I was a big fool. This time I’m flat on my back instead of the stool.”

When the fight was over and the champ left town

Everyone for Liston wore a big frown.

In Ali’s camp is old-time comedian Stepin Fetchit. He sings and dances and keeps everybody “loose.” He also reportedly has taught the champion a secret punch. He calls it the “anchor punch” and says he learned it from the immortal Jack Johnson who told him to pass it on, when the right man came along. Nobody has heard of an “anchor punch” and attribute its appearance now to Ali’s usual bravado. “It’s my secret,” Ali insists. “You’ll believe it when you see it.”

Ali, at 23, is a stronger, better fighter than he was for the first Liston bout. He is supremely confident. “Last time I was ducking just to get away,” he explains. “This time I’m looking to set him up.” He tells the world, “The Secretary of the Interior should declare my face a natural resource,” and tells his manager, Angelo Dundee, he may hide a muleta in his boxing trunks and play Liston like a matador with his bull.

A week before the fight, however, a cloud appears that has little to do with Sonny Liston but which threatens to upset the fighters more than right-hand counters. There are police reports from New York that a red Cadillac carrying a Black Nationalist assassination squad is enroute to Maine to avenge the shooting of Malcolm X, a Black Nationalist who defected from the Black Muslims. Ali, the most prominent Muslim in America, is the likely target. A special police detail from New York slips quietly into Lewiston.

State police increase their security around Chicopee. When Ali runs in the morning he sees police hats poking from behind bushes along his route. “I’m too fast to be hit by a bullet,” Ali tells reporters, most of whom feel they assuredly are not. There are reports that bullet-proof shields have been ordered for the press section and the Boston Globe takes out extra insurance on five of its sportswriters. “I don’t want Lewiston to go down in history as the place where the heavyweight champion was killed,” says Lewiston police chief Joseph Farrand.

On his last day of workouts before leaving for a Holiday Inn near Lewiston where he will stay three days before the fight, Ali is leaning against the ropes sparring with his boyhood friend from Louisville, Jimmy Ellis. Ellis is a light heavyweight who six years later will meet Ali in the ring for keeps, but now he is trying to prepare Ali for Liston’s body blows. Ali is not at his best. He has argued with his wife, Sonji, who balks at the Muslim strictures: no makeup, no dancing, no short dresses. It is an argument that will persist until their divorce six months later. Ali is wondering what to do about her when suddenly Ellis crashes a right to his ribs.

In his room Ali lies down and rubs his side with wintergreen and alcohol. Even though he is known for his boxing and his speed rather than his punching power, he vows to go for a quick knockout. He cannot afford to let Liston hit the side. In their first fight, he remembers, Liston hurt him plenty with body punches. He thinks of the dream and considers this his sign that he must catch Liston unawares. He leaves Chicopee early the next morning. He has boasted he will” raid the Bear’s camp” and Saul Feldman has tied two black bears from the state game farm to posts outside the Poland Spring House in anticipation. Ali pulls up to the Holiday Inn in his brightly painted bus he calls “Big Red.” Even though he is three hours early, there are several hundred people waiting for him. He stands on the balcony and shouts: ” I am the savior of boxing. You’re looking at history’s greatest fighter. There will never be another like me.” Everyone laughs. Then Ali goes inside and lies down, holding his side. He has forgotten about raiding the Bear’s camp, and the black bears cough on their chains until darkness comes, and they are trucked back to the game farm.

Tuesday, fight day, is the biggest day in Lewiston since John Kennedy held a rally in the park in 1959. The crowd begins to gather at twilight, assembling on a hillside overlooking the Youth Center, armed with binoculars, looking for celebrities. Newly erected transmitting towers rise behind them, ready to beam the fight for the first time to Europe, Africa, and Russia. Western Union personnel, crammed into trailers in the parking lot, try frantically to keep pace with words, already half a million strong, more than for any fight before. UPI has grabbed the four fastest track men from local Bates College and has them primed to race down the smoky aisles into the night with round-by-round reports clutched in their hands.

Ali arrives at 9:15 in his bus. He enters by a rear door through a cordon of state policemen. Around him a security force of over 300 men, the largest ever for a sporting event, search pocketbooks for concealed weapons. Ali appears unconcerned. As he disappears down a corridor he is singing at the top of his voice, “Let’s Dance.” When Liston arrives he is dressed in blue jeans and a sweatshirt. He walks past the troopers saying nothing, staring straight ahead. Sam Michael sits five rows back from ringside. There is nothing left to do. He had constructed three rings before this last one, trucked at the last minute from Baltimore, satisfied Angelo Dundee who regards a ring as his fighter’s home for 15 rounds. It is obvious there will be no sell-out — in fact the 4200 announced attendance will be the lowest for a heavyweight title fight in modern times — but Michael is happy. Intercontinental has promised Michael the rematch should Liston win as expected. “If the fight is a corker, Lewiston will be the fight capital of the world,” he tells friends.

The referee is Jersey Joe Walcott. He is a former heavyweight champion who once was belted out in two minutes by Marciano with jeers of ” Fake! Fake!” ringing in his ears. He is a popular man with an infectious smile whose previous work as a referee in a title bout provoked controversy.

The knockdown timekeeper is Francis McDonough, a small, bespectacled 63-year-old retired printer who is tanned from a winter in Florida. His job is to count off the seconds a fallen fighter remains on the canvas, sweeping his arm up and down as the referee counts in unison. Since Maine rules stipulate only the referee can stop a fight, he is merely a beacon a point of reference by which to pick up the count. In a glaring oversight, Walcott never locates his knockdown timer before the fight. When the crucial moment arrives, he will look in vain for the small man barely visible over the ring apron.

The official timer is a 55-year-old high school teacher named Russell Carroll. He has timed fights for three decades. He was timekeeper at the world’s quickest fight — 10-1/2 seconds — that ended when AI Couture ran across the ring a split second before the bell and belted his opponent as he turned from his corner. Afterwards the rules were changed, so that record time will stand forever. There is no official clock hovering high above the crowd as in Madison Square Garden, so his stopwatch must supply the official time. This is the first time he will time a fight without his personal watch. His own watch does not have a reset button, that when pressed sets the time back to zero. The one provided by the boxing commission does.

In the locker room Bundini Brown smears vaseline into Ali ‘s shoulders, working it into the torso with vigorous strokes. Somebody leans into the room and shouts, “Ten minutes!” Bundini wipes the vaseline off with a towel. Ali takes a deep breath and walks to the rear of the locker room where he says his prayers.

Robert Goulet stands in the center of the ring, looking magnificent in a tuxedo, and offers prayers of his own: in a few minutes his rendition of the national anthem will be heard around the world, and he cannot remember the words. Somewhere between his car and this ring he has lost his palm notes. He was raised in Canada and “The Star-Spangled Banner” has always been a troublesome work. When he climbed into the ring reporters at ringside heard him mutter, “What am I going to do?”

That he cannot hear when the organ begins does not help. Only when technicians wave frantically at him to get going does Goulet realize that the organ is careening along on a solo. The song belts him immediately: “Oh! Say can you see by the dawn’s early night?” and bedevils him the rest of the agonizing way. (At another juncture ” fight” is substituted for “night.”) When he finishes, the first UPI trackster streaks away carrying this report: “The Clay Liston fight has begun and the following is a round-by-round report.” By the time he reaches the trailers, Western Union has a message for him. As Russell Carroll strikes the gong for round one, he is gripped with a sensation that “something is going to go wrong.”

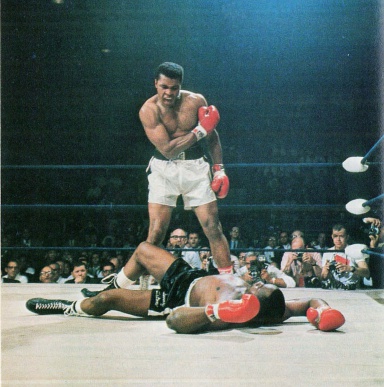

Ali circles, holding his elbow close to his side. Liston moves cautiously, sluggishly, to meet him. Barely over a minute slides by with only minor skirmishing when suddenly Liston lunges from a crouch. His left foot is off the ground and he is off-balance. At that moment Ali bounces off the ropes and throws a right that travels eight inches before landing flush on Liston’s cheekbone with a downward twist. The blow snaps Liston’s head down at the same time it lifts his foot high off the canvas. Most people do not see the punch, only Liston’s collapse, as though a wind gust has tossed him to the ground.

Ali is hysterical. “Get up and fight. You’ re supposed to be so bad. Nobody will believe this,” he yells, standing over Liston. Walcott is afraid Ali will kick Liston and he tries to steer him to a neutral corner. But Ali is uncontrollable. Liston is not knocked out. But neither is he in. His is a misty world. Francis McDonough dutifully slaps his arm up and down on the table. At the count of eight, Liston is on one elbow, but Ali is glaring down, his fists ready, and Liston, who has not heard a referee ‘s count, slides back down.

By the time Walcott has pushed Ali back, McDonough’s count has reached 20, where he stops. Liston has fought grimly back from his mist, and as he finally stands he blinks in bewilderment as though emerging from a tunnel. Now Walcott assists Liston, holding him while he looks in panic around the ring apron for the knockdown timer. Not knowing what to do, he dusts off Liston’s gloves, and, as incredible as it seems, the fight continues.

This galvanizes Nat Fleischer into extraordinary actions. Fleischer is the grand old man of boxing, the feisty editor of Ring Magazine.

He runs to Russell Carroll, minding his stopwatch, and yells, ” Stop the match! The fight is over!” Carroll, flustered, presses the reset on his watch, without realizing it. He is not sure if the fight is on or off. Ali is hitting Liston again, so Carroll restarts his watch.

Fleischer turns to Walcott who wants somebody to get him out of a horrible mess.” Joe,” he screams, “the fight is over! ” Walcott turns away from the fighters. Liston is trying gamely to fight back and later one writer wondered, What would have happened if Liston had knocked Clay out while the referee consulted with Fleischer and McDonough? Walcott is convinced that Liston has been counted out.

When Walcott separates them and leads the challenger away Liston thinks the round is over. He thinks he was lucky to escape that one. He looks back and sees Ali’s arm raised by Walcott. Only then does he know the fight is over.

The fight establishes several dubious firsts. It is the first fight stopped by a magazine editor. It is also the first fight stopped without the referee’s counting one second over the fallen fighter. And it is the first fight to record “official” times of 1 minute, 1:47, and 2:12, the discrepancies due to Carroll’s inadvertent resetting of his watch, and to differences of opinion as to when the fight was actually over.

At 2 A.M. Liston serves coffee in the Mansion House, while his wife Geraldine cries softly in a corner. “Fourteen years is a long time,” she says. “I’m glad it’s over.” But Liston will fight again. He wins 16 straight in a comeback that ends when Leotis Martin knocks him out. His last fight is in a smoky little fight club in Jersey City on June 29, 1970. Six months later he dies in his home, alone. When he falls his fists evidently smash against a bench, for when he is found seven days later the bench lies in splinters by his head.

Ali is stung by the cries of “Fake” that fill the hall. “I hit him hard enough to knock out any man,” he says. “I told you I had a secret,” he adds. “That was my anchor punch. It’s lethal.” After the fight, Ali fights many times, but the anchor punch is not heard of again.

Only a handful of reporters actually saw the punch. Those that did were convinced of its power. However charges of “fix” filled the papers for days. Jimmy Breslin called the fight “the worst mess in the history of sports.” Another writer added, ” It was boxing’s shot in the arm — embalming fluid.” Of all the Maine officials, Francis McDonough suffered the most. He said his job was to count over a fallen fighter, and that he did. He did not tell Walcott to stop the fight, only that Liston had been down for at least 20 seconds. He stopped speaking to reporters. When he died three years later, much of his obituary concerned his role in the ill-fated fight, a task that from 68 years of life consumed 20 seconds.

Lewiston today enjoys a certain pride in the fight. After all, how many people can name where Ali fought Zora Folley, say, or Cleveland Williams. But go anywhere where people are talking boxing and to start an argument you just say two words: “Lewiston, Maine.”

“It’s part of our lore and legend,” the man says, and for Lewiston, at least, the fight will never really be over.

I was there. I was 17 and a senior at Brunswick High School. I am from the small town of Topsham, Maine. I had bet many of my BHS classmates that Ali would win the fight. I had about $75 in bets. As a Senior I worked about 30 hours a week in Senter’s, a Brunswick ladies store. $75 was about two weeks pay. I had no significant financial responsibilities at the time, so $75 was just lark money.

Because I could not easily find a place find a place to park close to the Arena, I was just entering the Arena when the crowd erupted. After, I drove slowly home down RT 196 to Topsham.

I have always thought of it as a thing I did. Now at 67, I remember it as a great adventure. Time doth glorify memories.

2/19-2015 Bonita Springs, Florida

One of the great write-thru’s of modern boxing. Loved reading this, first when published and on second read in 2020.