Angels Among Us | Ordinary People with Extraordinary Hearts

Each year, we spotlight ordinary people with extraordinary hearts in our ongoing Angels Among Us series. This year, three inspiring stories.

Give a kid a chance to be a leader, say Coaching For Change co-founders Peter Berman (left) and Marquis Taylor, and good things happen, both at home and in the classroom. “Kids step up to the plate when they’re given responsibility,” says Taylor.

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

CHANGE MAKERS Marquis Taylor + Pete Berman

It’s been a back-and-forth game when Derrick Webb grabs a defensive rebound and pushes the ball toward his team’s basket. Crossing mid-court, he slows down near his coach, Rodrigo Fabio Da Cruz Bento, a freshman at Brockton (Massachusetts) High School, who stabs at his clipboard with a pencil as he talks.

“Get the ball to Jose [Depina],” he says, just loud enough for his point guard to hear him. “Pass it to him.”

Webb nods. When he gets to the top of the key, he flicks a bounce pass to his teammate, positioned 15 feet from the basket. Depina collects the ball and fires up a shot, which cleanly goes through the net.

“There you go!” says Bento, as the player trots back to play defense with a wide smile. “There you go!”

It’s a scene that plays out for the next several hours at Brockton’s East Middle School. Middle school kids are coached and spurred on by high school kids. They, in turn, are overseen by a small group of juniors and seniors from nearby Stonehill College, who give counsel on how to give the younger kids directives, maintain their motivation, and keep them focused. Students helping students, helping students.

In Brockton, an economically challenged city where the high school dropout rate hovers around 10 percent and extracurricular budgets are never safe, this innovative private after-school program, known as Coaching For Change (C4C), builds on this basic idea: Give a young person ownership over what they’re doing and they’ll feel empowered to not just do well, but strive to take on more. On the court, in the classroom, and at home.

The core of it is taught through basketball coaching. Struggling high school students are thrust into the role of being leaders. They organize games and tournaments; they draw up plays and push their players to play harder. Doing this, they find their natural voice as a role model. When you have to teach someone, the reasoning goes, the choices you make, the way you behave, is also altered. Success breeds other kinds of success.

“Kids step up to the plate when they’re given responsibility,” says C4C co-founder Marquis Taylor, who started the program in 2011. “What we’re doing is getting these kids to understand that what they’re doing as a coach requires basic leadership skills, and then getting them to transfer those skills to their community and classroom.”

It’s a story Taylor knows well. A native of Los Angeles, he leveraged his basketball talent to expand a vision for himself that went beyond the streets of his own struggling neighborhood. He earned a full basketball scholarship from Stonehill, then embarked on a career in finance after his 2006 graduation. But the memories hung on, of the coaches who’d mentored him, and of the people he grew up with who never had the chances he did.

“There’s the familiar model,” says Taylor. “You’re a good athlete and you get attention. Hopefully, you get a scholarship, and then you’re off to the races and that changes your socioeconomic status. But what happens when you get cut from the team or the funding for the program gets cut? Kids that are high-achieving get awards and access, and kids at the lower end get access to different services. But then you have all these kids in the middle where nothing is happening. They have untapped potential that needs to be recognized.”

In 2010, Taylor quit his job, enrolled in a master’s program in teaching at Smith College in Northampton, and directed a summer sports program at the Brockton Boys and Girls Club. There, he formed an early incarnation of C4C. Older kids coached and mentored younger ones. When summer ended, kids asked that it continue. Taylor made sure it did. He built an after-school program, sleeping on friends’ couches or in his car just so he could afford the $7,000 to get it launched.

By 2012, he’d landed a $70,000 grant and partnered with Pete Berman, a Sudbury native who’d returned to Massachusetts after working for the United States Soccer Federation, to expand C4C. Over the last four years they’ve built a program that extends far beyond the basketball court. In between the whistle calls and the sounds of sneakers streaking across the floor, universal themes are shared: “Pass the ball. Don’t get mad. Help your teammates.” It’s basketball advice, but it’s also the kind of instruction that has its place in life off the court.

But it’s a misnomer to call C4C just a sports program. At East Middle School, 128 students split their two-day-a-week after-school sessions between the gymnasium and the computer lab, where they work on projects that range from writing and publishing a magazine to producing podcasts and crafting poems, raps, and songs. A third day is devoted strictly to the program’s 32 high school students for homework support and test preparations. Berman and Taylor track their academics through weekly progress updates filed by the school and report cards.

“A few years ago we had this kid,” says Berman. “He struggled academically, had been kicked off sports teams, and had a tough home life. He started the program and he didn’t say a word. But after that first semester his teachers asked me to save a spot for him because the program was all he talked about. The more time he spent with us, the more he opened up and asked to take on other responsibilities. He made a point of coaching some of the hardest-to-reach kids. He’d been where they were and they listened to him. I remember walking into school one day, and he grabbed me and said, ‘I didn’t show you my report card.’ It was all A’s and B’s. Now he’s on the track team and he’s one of the fastest kids in the state.”

C4C tries to show these high school kids a future that may be bigger than they imagined for themselves. Four times a year, Taylor and Berman lead the students on college campus visits. “It’s a chance to expose them to an atmosphere that is foreign to them,” explains Taylor. “Many of our students are first-generation and college is not something that they see as a natural next step.”

Can this model work elsewhere? Taylor and Berman believe it can. As they have with Stonehill, they see a chance to partner with additional colleges to bring C4C to other under-resourced schools throughout New England, and ultimately, around the country, in an effort to replicate the kind of results—better grades and school attendance—that they’ve helped their Brockton kids achieve.

“This program gives these kids a connection to something,” says Charlene Mont-Rond, a social studies teacher who serves as C4C’s site director at East Middle School. “Kids aren’t ending up in the principal’s office and they’re showing up more at school. A lot of our current eighth-graders are asking about becoming mentors. They’re thinking about the future and that’s great.”

For more on C4C, visit: c4cinc.org

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

EVERYBODY LOVES ROLAND Roland Bousquet

Sometimes the most extraordinary places can be found in unexpected spots. One such destination exists in a plain downtown building in Mexico, Maine. There, you’ll find Roland Bousquet, who hosts a monthly Veterans Appreciation Day for anyone who has served in the armed forces.

On the third Tuesday of every month, he opens his doors at 10 a.m. and over the next 12 hours welcomes his guests into The Paper Plate, a converted function space that resembles a living room. There are couches and chairs, fresh coffee, and instruments and games to play. Some visitors come for an hour; others stay much longer. Nobody pays for a thing. “It’s a place for them to hang out, meet new friends, and just have a good time,” says the 70-year-old Bousquet, who lives in an apartment above the retired storefront space.

Bousquet launched Appreciation Day in November 2014, but really, it was half a century in the making. In the early 1960s, a medical condition denied Bousquet the chance to continue his Navy career and serve in Vietnam. Over the next several decades, he built a life in his hometown. He ran the family’s general store, later working as a bus driver and school custodian. All the while feeling guilty about not being able to serve his country. Even now, it still chokes him up.

“In my heart I felt I deserved to fight with my friends and do my fair share,” he says. “This is my way of offering my duty to my country. I just had to do it.”

The (mostly) men filter in throughout a day. Sometimes only a few; other days the room is packed. Some have known combat. The names of the wars change: Korea, Vietnam, Desert Storm, Iraq and Afghanistan; and the faces and bodies of the men change with them: the aged and the younger. It doesn’t matter in this room since there is rarely talk of war. Instead, they talk about the weather and sports and children, the price of oil and the economy—but what they are saying just by walking in there is that they are not alone. Bousquet has given them the gift of shared space. In return they’ve given him something, too. A few months ago, he hosted 25 visitors for dinner. “I was in my glory,” says Bousquet. “I was hustling back and forth like a chicken with his head cut off. At one point, a song broke out. I just had the best day of my life.”

Bousquet’s generosity does not stop here. He loans out his building to other charities. He builds birdhouses to give to children at the local hospital, and during the holidays he gives candy and homemade cookies to police and fire workers, as well as town employees. In a struggling mill town like Mexico, where the past can sometimes overshadow the present, Bousquet’s outreach has not gone unnoticed.

“He’s an all-around good guy,” says Mexico’s town clerk, Penny Duguay. “The kind of person who would do anything for you. You wouldn’t find a person in town who has a bad thing to say about him.” Bousquet shrugs off the praise. For him, these acts of kindness are as essential to him as breathing. “You just never know what someone has lived through,” he says. “I want people to feel appreciated. That’s my job. That’s what I do.”

Photo Credit : Dana Smith

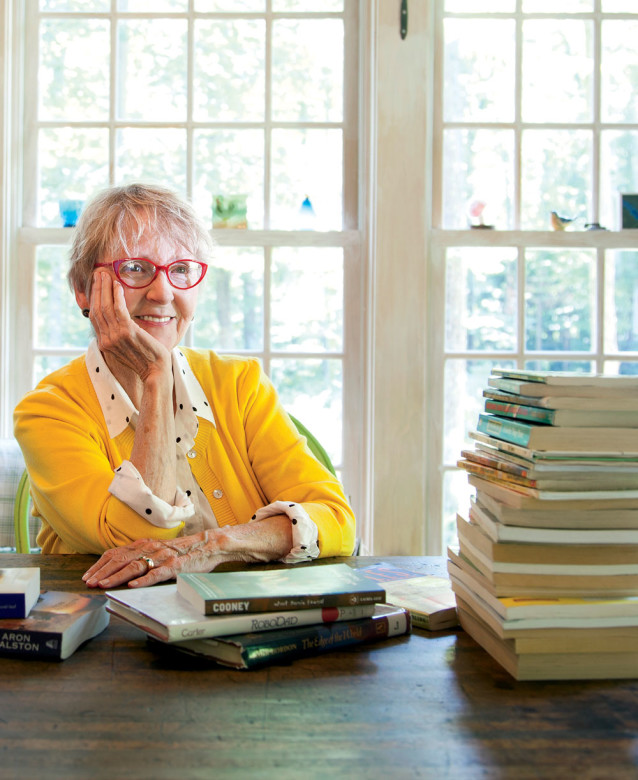

THE BOOK LADY Nancy Cayford

The conversation is still burned into Nancy Cayford’s memory.

In the fall of 1993, Cayford, a Dublin, New Hampshire, resident, who had been working to help address the poverty on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, was chatting with a 10-year-old girl she’d met there.

“What would you like to be when you grow up?” Cayford asked.

“Nothing,” the girl replied.

“She couldn’t come up with a vision for her life,” Cayford explains. “I was stunned.”

And propelled to act. She wanted to give the kids she’d met a chance to discover a bigger world. She couldn’t bring them to those places, so she did the next best thing. Back home, she and a friend organized a book donation drive, and over the next several weeks collected more than 600 titles to give to the Pine Ridge schools.

It was a pivot from her previous attempts to help the community. But then, Cayford has never feared change. A Maine native who’d grown up on a potato farm in Aroostook County, Cayford began her working career as a nurse, then pursued her dream to become an artist and went on to become perhaps the country’s preeminent maker of decorative floor-cloths, a popular 18th-century home accent. Her work is displayed in homes all over the country, including Old Deerfield, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Then in 1991, Cayford, who was about to turn 50, felt the call to do service work. It was on a stop out West, during a cross-country trip with her husband, Phil, that she discovered her purpose was to work with the Oglala Lakota. She closed her business, spent a year studying Native American culture (“I didn’t want to just come in as some do-gooder”), and carefully forged contacts within the community. She began by helping struggling artisans establish businesses, then worked to set up a bike donation program. During one visit she packed more than 100 bikes inside, on top of, and strapped around her husband’s VW van for the drive to Pine Ridge.

But it’s been the book drives that have fueled her work these past two decades. Through her nonprofit, Friends of the Oglala Lakota, Cayford works with a team of dedicated volunteers from southern New Hampshire to collect and donate thousands of titles each year. It’s a group effort to be sure, but as it’s always been, it’s Cayford who makes it all happen.Every age group is accounted for; every school on the reservation, a recipient. Boxes are packed in Cayford’s retired art room and sent to Pine Ridge throughout the year. Every October, she visits the reservation for two weeks, visiting schools, meeting old friends, and checking in on what kinds of books are needed. Among the teachers and librarians, she’s simply known as The Book Lady.

“It’s in my blood to help these people out,” says the now-75-year-old Cayford, who has expanded her mission to fund small college scholarships for high school graduates. “I love them and I love the land. It reminds me so much of Maine. I’m not going to stop. I continue on.”

For moreon Friends of the Oglala Lakota, visit: lakotafriends.org

LEARN ABOUT MORE ANGELS: 2015 Angels Among Us2014 Angels Among Us2013 Angels Among Us

Ian Aldrich

Ian Aldrich is the Senior Features Editor at Yankee magazine, where he has worked for more for nearly two decades. As the magazine’s staff feature writer, he writes stories that delve deep into issues facing communities throughout New England. In 2019 he received gold in the reporting category at the annual City-Regional Magazine conference for his story on New England’s opioid crisis. Ian’s work has been recognized by both the Best American Sports and Best American Travel Writing anthologies. He lives with his family in Dublin, New Hampshire.

More by Ian Aldrich