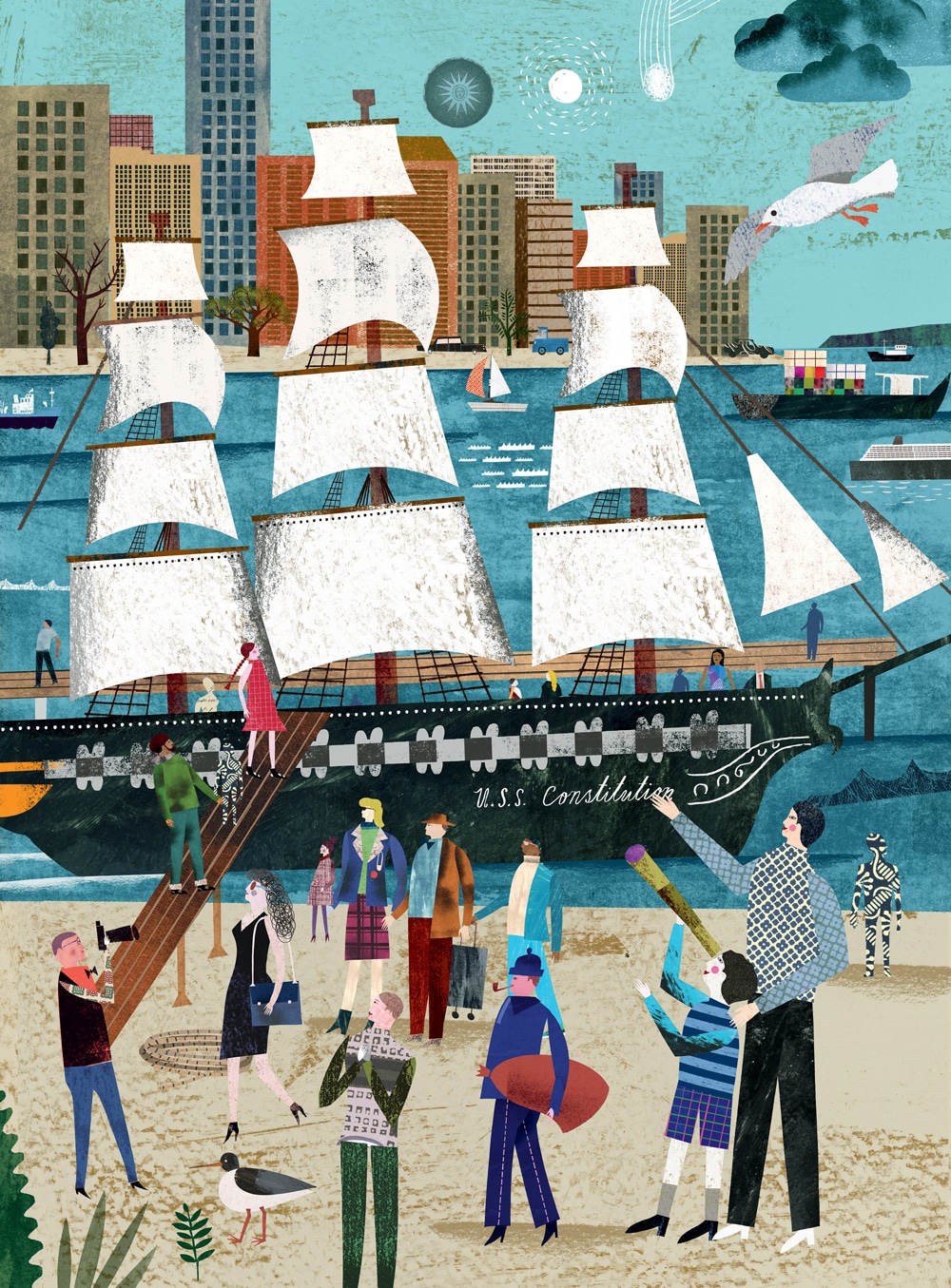

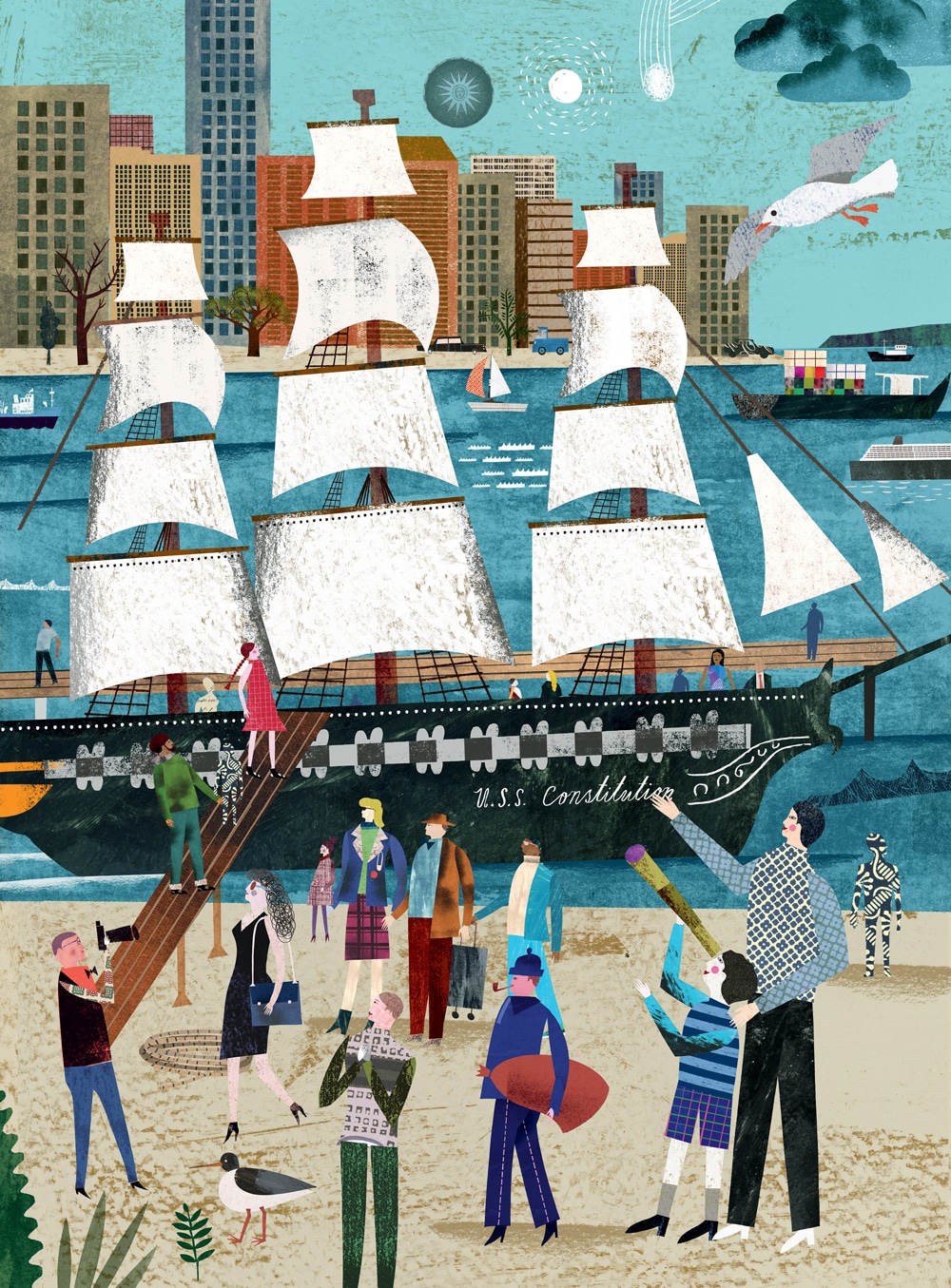

The USS Constitution & Voyages of the Imagination | New England from the Water

Even without leaving the dock, legendary ships like the USS Constitution can carry us away.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

It takes great effort to convince my son that what we are approaching is not, in fact, a pirate ship.

The USS Constitution stands tall and proud at its wharf in the Charlestown Navy Yard, its masts peeking above the museums clustered alongside like barnacles. My son remains skeptical. In the mind of a 6-year-old there is only one use for so much sail and timber, and it usually involves eye patches.

“So it’s an army ship?” he asks. Close enough.

It’s a cold and rainy Saturday in Boston, but the tour group is still packed. While historic homes might have a hard time bringing in the crowds, historic ships never seem to—even with so many to choose from. New England’s waterfront is littered with vessels you can sail only in your imagination. Whaling ships, warships, pleasure yachts, and submarines. Ships with a single linen sail, and ships with nuclear-driven turbines. Ships that carried cargo, and ships that ferried our ancestors. All of them preserved and mounted to the dock like so much nautical taxidermy.

Our guide leads us aboard and dives into her presentation. Tours on historic ships don’t vary much—they all draw on the same maritime greatest hits. There’s the review of the cramped living spaces, the talk of limited diets. If the ship dates before the 20th century, the fun fact that beer was a healthier choice than water will likely be mentioned. Our guide’s explanation of how sailors used the bathroom is a crowd-pleaser I’ve heard on at least six other ships.

Of course, the tour is never the main event; the ship is. There’s just something about being on these old vessels that speaks to so many of us. My son clearly has the bug. He bounces from one compartment to the next, filling my phone with grainy photos of his discoveries and starting every sentence with “If we were real sailors….”

I admire the honesty of his enthusiasm. He is unapologetically here to role-play. We adults have to at least try to hide it. Hands buried in our pockets, we lean over cannons with a look of practiced disinterest, while in our minds the deck crashes and splinters under the force of incoming fire.

Is it the sense of adventure that draws us here? Did we simply watch Master and Commander too many times? I don’t think so. Mankind has waxed poetic about life at sea since we first learned how to lash two logs together. In our culture, the image of a person standing at the bow of a ship evokes the purest sense of freedom, as though this improbable perch is where we were all truly meant to be. John F. Kennedy once said, “We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea … we are going back from whence we came.”

Freedom? On the sea? Freedom is a creature of the land. Freedom is a full belly and a warm bed. Freedom is the ability to walk 100 feet in any direction you choose without plunging into the abyss.

A ship on the ocean is a prison surrounded by the world’s widest moat. It has often been a place of grueling labor and corporal punishment. On ships of yore, the only person who was remotely free was the captain, and he still ran the risk of contracting scurvy or becoming the chew toy of a great white whale.

We know all this, and yet the romance is undeniable. As I follow my son down the narrow steps from the gun deck to the crew quarters, I feel that tingle in my spine. We are in a magical place, even if we can’t quite name the spell we’re under.

Touring the deck where row after row of hammocks would have hung, I can imagine myself lying there exhausted, freezing, or sweating, depending on the latitude, and I know I would have been miserable. But perhaps that’s secretly the draw. Perhaps the romance and the adventure—all the swashbuckling and cannons—are just a veneer over some deeper yearning.

You see, the one thing all these historic ships have in common is that they represent enormous gambles that paid off. The crew of the Constitution set sail to battle the British navy, the largest and most impressive armada of the time. This ship should have been sunk, but it wasn’t. The settlers who boarded the Mayflower were on a long-shot colonization bid. They all could have been lost in a storm, but they weren’t. The sailors who signed on to the Charles W. Morgan volunteered for the ridiculous task of fighting whales from a rowboat. No one should have walked away from that, but many did.

Every museum preserves a moment in time. Maybe the reason I’d rather tour a historic ship than any of the historic homes where these sailors went on to live is because the ship preserves the moment when the story was in doubt—the moment when people were tested, and passed. Historic homes remind me too much of my own life: the warm hearth, the crowded kitchen, the sense of gentle aging. It’s comfortable, but sometimes that is the last thing we want.

Most of us today play for much lower stakes than the men and women who risked their lives on these old creaking ships. We should all be thankful for that. But let’s not deny the existence of that reckless urge to risk it all, to sign our names to some audacious task and walk wide-eyed into the crucible. Can we be blamed for coming aboard these ships and fantasizing about cutting the ties that bind and steering ourselves toward some challenge? Is it crazy to think that in that moment when we stand exhausted and fist-clenched before the eye of the storm, we might see something in ourselves that we never saw before?

My son’s hand finds mine as we mount the gangway and leave the Constitution behind. The day is young, and we are bound for more pedestrian adventures. I ask if he had a good time, and of course he says yes, though I’m not really sure we had the same experience. On the dock, we stop for one final photo to remember the day by. He poses before the ship, the masts framing his exuberant face, then he clenches one eye closed and lets out a boisterous, triumphant “Arrrrrrghhh!” —Justin Shatwell

For more information on visiting the USS Constitution and its namesake museum, which are open year-round, go to ussconstitutionmuseum.org.

Docked and Loaded Sail through history on a lore-filled museum ship.

Thanks to New England’s four centuries of maritime history, the region is rich in preserved specimens of the shipbuilder’s craft—from wooden merchant vessels to modern iron fortresses—that still welcome visitors aboard. And landlubbers, rejoice: This is adventure sans seasickness.

Mayflower II After being gone nearly four years for a stem-to-stern restoration, the pride of Plymouth, Massachusetts, returns to its home berth in May. And since 2020 is also the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing, expect a doozy of a homecoming. plimoth.org/mayflower

USS Massachusetts Long enough to carry two Statues of Liberty laid end to end, the battleship nicknamed “Big Mamie” anchors the world’s largest collection of World War II military vessels, at Battleship Cove in Fall River, Massachusetts. battleshipcove.org

Charles W. Morgan From Arctic ice to typhoons, this 1841 whaling ship navigated countless perils during 37 globe-trotting voyages. Today America’s oldest commercial vessel still afloat enjoys its well-earned rest at Connecticut’s Mystic Seaport. mysticseaport.org

USS Albacore Located just a stone’s throw from the shipyard where it was born, this 1950s Navy research sub in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, offers hands-on exploration and an audio tour featuring the stories of former crew. ussalbacore.org

Ticonderoga The fact that it took 65 days to haul this 1906 steamboat two miles from Lake Champlain to its resting place in a field at Vermont’s Shelburne Museum is just one chapter of the fascinating tale of “the Ti.” shelburnemuseum.org

I had the wonderful privilege of viewing Constitution’s 200th birthday sail from a vessel just outside the security perimeter. The day was overcast, with just enough breeze for her to move under sail alone. Too great a risk to her old timbers to try again; I’ll always treasure that magical sight.

I had my military retirement ceremony on Old Ironsides in 2013.