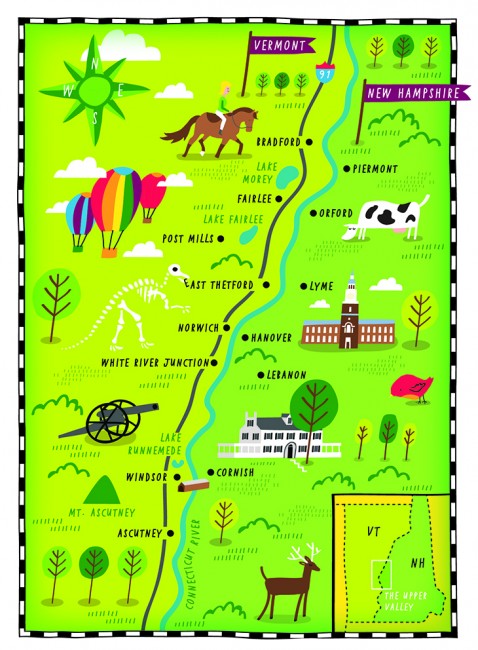

The “Upper Valley” of Vermont and New Hampshire

The “Upper Valley” along the Vermont/New Hampshire border is a collection of little-known small towns featuring the New England we all look for.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Up we floated above Lake Fairlee, over green shores and kids’ summer camps. Whoosh … and up again, the hot-air balloon rising over a ridge and down over woods patched with cornfields, on toward the Connecticut River. On the Vermont bank, a dozen or so small figures were saluting the sunset with tai chi. We hovered briefly above an iron bridge spanning the narrow ribbon of water and drifted southeast over New Hampshire woods, settling down gently in a Lyme hollow.

Fairlee, Vermont, and Lyme, New Hampshire, are in the “Upper Valley,” a distinctive region that at its heart includes towns twinned on opposite banks along a roughly 40-mile stretch of the Connecticut River: from Windsor, Vermont, and Cornish, New Hampshire, in the south to Bradford, Vermont, and Piermont, New Hampshire, in the north. The name was coined in the 1950s by the Valley News to define its circulation area, reaching into both states. What fascinates me is the way it has stuck to an area that includes some of the same communities that in the 1770s attempted to form the state of “New Connecticut,” with Dresden (now Hanover, New Hampshire) at its center. Even today, the river remains more of a bond than a boundary.

Visitors can easily prowl both sides of the river. Interstate 91, set high above the Vermont bank, offers a quick route up and down the valley, but the old highways–New Hampshire Routes 10 and 12 and U.S. Route 5 in Vermont–thread through fields and villages. Older roads hug the river in places, while byways branch invitingly into the hills. Formal attractions are few, but you’ll find river landings, many farm stands, and frequent unexpected discoveries.

Last summer along Route 244 in the Vermont village of Post Mills (in the town of Thetford), I happened on a dinosaur, with a smaller dino beside it, both cobbled from recycled wood. The adult “Vermontasaurus“ is 122 feet long and 25 feet high, fashioned by local students from a collapsed barn roof ; the “babysaurus” was born with blowdown from the larger sculpture, delivered by Hurricane Irene in August 2011. Several eliders and a tow plane rested in the large field, beyond which, a sign announced, is Post Mills Airport. Nothing told me that the long, nondescript wooden building beside the field housed one of the world’s largest collections of hot-air balloons, airships, and contraptions that were never meant to fly but do.

Brian Boland, creator of both the sculptures and the museum, was tinkering around out front. We struck up a conversation, and he told us that virtually nobody in this country was offering hot-air balloon rides in the 1970s when he began making his own and flying them. I soon learned that he’s known internationally as a hot-air balloon designer–and locally as the “Willy Wonka of the Upper Valley.”

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Boland’s adventurous spirit is infectious. In short order I ventured up in his balloon, and then a few weeks later I returned and set out on the Connecticut River in a rented kayak, putting in a mile north of the Cornish-Windsor Bridge, New England’s longest covered bridge, backed by the hump of Mount Ascutney. The mountain is in Vermont, but the river and the bridge are in New Hampshire, because that’s what King George III decreed some two and a half centuries ago. Many disputes later, the boundary was set at the low-water mark on the Vermont side by the United States Supreme Court in 1933.

My takeout spot appeared three miles below the bridge. I climbed through a meadow to the barn that houses North Star Livery. Thirty years ago, just as the river was finally recovering from a half-century’s worth of abuse, Liz Drummond began renting canoes from her family’s riverside farmhouse on New Hampshire Route 12A in Cornish. Today dozens of boats are stacked against the barn, which doubles as check-in desk for North Star and stable for the draft horses that farrier John Drummond raises.

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

I picnicked at the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish. Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907) is best remembered for his public pieces, including the Shaw Memorial on Boston Common and the General William T. Sherman statue at the entrance to Central Park, among many. With his wife, Augusta, he bought a vintage 1817 tavern, set high above the river here. Initially a summer retreat, “Aspet” became a year-round home; as commissions poured in, he added a studio and other buildings, and the property was elaborately landscaped. The house retains its original furnishings, but it’s the 195-acre grounds and the beauty of the reproduced sculptures that make this a must-see destination, especially on summer Sundays, when the public is invited to picnic before a (free) concert on the lawn.

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Old farms were selling cheap in the wake of the Civil War; many of the sculptor’s prominent artist friends came to visit and soon bought nearby homes of their own. This “Cornish Colony” flourished from 1885 to 1935, and its spirit lingers today. Cornish was home to painter Maxfield Parrish until his death in 1966; writer J. D. Salinger lived quietly in Cornish until his death in 2010.

Whether Saint-Gaudens ever climbed Mount Ascutney, nobody knows. Certainly it dominated his view, and a hiking trail there dates from 1825. I’d never thought of climbing it myself before last summer. Ascutney is also the site of one of the oldest Vermont state parks, good for camping, mountain biking, and hiking, and a popular launch spot for hang gliders. A well-surfaced “parkway” spirals gently up from Route 44 in Windsor to a parking lot 2,800 feet above the river, and from there trails access various views. I headed up the 0.8-mile trail to the summit, not realizing how rugged the short climb of 344 vertical feet actually is. But what a reward: a 360-degree panorama from the fire-tower deck, sweeping into New Hampshire from the White Mountains down, and west and north across Vermont farms and forests, rolling into the Green Mountains.

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

When I descended, I drove north on U.S. 5 and then west along Route 244 again, turning north at Lake Fairlee, up a farm road and into the hills, drawn by a flyer for Open Acre Ranch. Its reasonably priced trail treks–fine-tuned to the ability of individual riders, on 400 private acres –sounded too good to be true. But this was the Upper Valley.

A small sign announced the ranch, and the horses looked promising. Owner Rebecca Guillette explained that she keeps around 40 mounts, catering to the summer camps on nearby Lakes Morey and Fairlee. She guided me out onto a dirt road and then onto narrower, leafier trails, lined with crumbling stone walls. We broke smoothly into a canter on the uphill stretches (I held gratefully onto the saddle horn), emerging eventually onto a high meadow, with views across to the Vermont hills and to the foothills of New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

What you don’t see is the riverside village of Fairlee, one of my favorite places to lunch, at either the Whistle Stop Cafe or the Fairlee Diner. Then there’s a must stop at Chapman’s Country Store, opened in the 1890s as a pharmacy, now specializing in hand-tied fishing flies, USGS maps, and tips on where to find walleyes and rainbow trout. It’s also a source of Mexican silver, Indonesian jewelry, wine, used books, toys, and more.

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

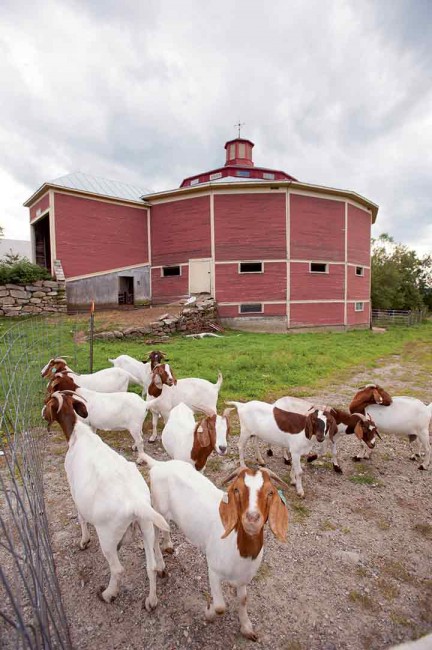

The roads in this quiet, northern end of the Upper Valley are beloved by bicyclists and about as good as it gets by car. North of Fairlee, the steep cliff face known as “the Palisades” gives way to open farmland along U.S. 5, with river views along the six miles to Bradford. A turn east at the light just south of the village leads to Farm-Way, Vermont’s answer to L.L. Bean, a family-run phenomenon spread over 16 acres, and a source of everything from shoes (25,000 pairs) to kayaks to syrup. Cross the bridge beyond to sleepy Piermont and New Hampshire Route 10; then head south through cornfields. Stop to buy aged Toma raw-milk cheese or ice cream at Robie Farm and, over the Orford line, rich cheddar, feta, buttermilk, or yogurt from the Devon cows at Bunten Farm, with its vintage barns and handsome 1835 brick house. One barn here houses Ariana’s, a small restaurant that’s literally “farm to table” and one of the best places to dine in the Upper Valley. South of the village, with its striking Federal homes spaced regally across a ridge above Route 10, you’ll find an 18th-century tavern housing Peyton Place, another outstanding restaurant.

From here the road keeps its distance from the water, but you can angle off onto River Road, dipping down beneath a covered bridge and along past more Federal-era farmsteads on the way to Lyme. River Road continues on, but I usually turn inland to the green, framed by buildings all sheathed in white clapboard, from the handsome 1812 Congregational Church and four-story Lyme Inn to the general store, post office, and commercial buildings housing finds such as Stella’s Italian Kitchen & Market and Long River Studios, a shop and gallery selling art and artisanal wares. Below Lyme, New Hampshire Route 10 keeps its distance from the river along the 10 miles or so to Hanover.

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Few college towns are as visitor-friendly as Hanover, New Hampshire, the geographical center and cultural hub of the Upper Valley. The Dartmouth Green doubles as the town common with a seasonally staffed information kiosk. Surrounding it are the historic and architecturally striking buildings of Dartmouth College, including the Hopkins Center for the Arts, a major performance venue; the Hood Museum of Art, with its outstanding collection; and the recently revamped Hanover Inn, a lodging and dining destination in its own right. South Main Street’s blocks are few but offer some remarkable places to eat and to linger. Ice-cream lovers will be happy to know that Forbes magazine recently rated Morano Gelato–the creation of Morgan Morano, who grew up in Hanover but perfected her skills working in Italian gelaterias–as home to the best gelato in America. (Bill and Pam Miles and John and Jenn Langus are the shop’s new owners; Morgan Morano is the business’s executive chef.)

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Across the bridge in Norwich, Vermont, the Montshire Museum–blending both states in its name–is a science center fit for a city. With hands-on exhibits there’s plenty here to stimulate curious minds of all ages and to demystify a whole range of scientific phenomena, from the valley’s morning fogs to the physics of bubbles. Outdoors you’re invited to manipulate the flow of water downhill and to identify bird calls and insect sounds along trails through 110 riverside acres.

Norwich is a gracious Vermont town, with Dan & Whit’s, a famously old-style general store, at its center, along with the welcoming Norwich Inn, known for good food and a fine brewpub. It’s also home to King Arthur Flour and its flagship baker’s store, a cafe, and a baking-education center, drawing fans from across the country.

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

South from Norwich, you might want to hop I-91 (exit 13) for the 19 miles back down to Windsor. Known as “the Birthplace of Vermont,” Elijah West’s tavern in Windsor is the place where delegates from both sides of the Green Mountains gathered to draw up a constitution for the “free and independent state of Vermont”: a sovereign republic (until it joined the Union in 1791). This Old Constitution House is now open to the public on weekends.

Even when it’s closed, though, I stop here and walk the path leading to Lake Runnemede, a local destination for birders and another good picnic spot. I think it’s the pond in Thy Templed Hills by Maxfield Parrish, depicting a mountain resembling Ascutney, towering behind the water. The original of this painting hangs in the local People’s United Bank branch nearby, and, although bank ownership keeps changing, the painting is here forever, a gift to the tellers from Parrish for “keeping my account balanced.”

There are more obvious attractions in Windsor, as well: the American Precision Museum, a mellow brick armory where rifles were first made with interchangeable parts just in time for the Civil War, and, north of town, the ever-evolving 34-acre Artisans Park riverside campus, with visitor-friendly enterprises that include Simon Pearce Glass, Harpoon Brewery and its beer garden, Great River Outfitters, the Vermont Farmstead Cheese Factory, and the 14-acre Path of Life Garden.

Photo Credit : Kindra Clineff

Squirreled away in a former freight shed down by Windsor’s Amtrak station, a wayside center offers visitor information about both sides of the river. It’s one of eight such centers along the 255 miles of river shared by New Hampshire and Vermont; it represents 30 years of concerted effort by a volunteer bistate commission, today almost forgotten, having achieved its goal: the 2005 formal recognition of the Connecticut River National Scenic Byway.

“Upper Valley” figures in the names of dozens of local organizations and businesses–and it’s where many residents will tell you they live, before mentioning which state. For me, it’s New England’s most distinctive bistate region, a place of constant discovery, even adventure.