A Chorus of Memories | A Celebration of Boston’s Black Nativity

Reconnecting with the soul of Boston’s Black Nativity on its 50th anniversary.

Members of the Children of Black Persuasion chorus sing “Mary, Mary, What You Gonna Name Your Baby?” in the 2017 production of Black Nativity.

Photo Credit : Idly GaletteEditors’ note: At the time of publication, the 2020 performances for Black Nativity had not been confirmed. For the latest updates, go toblacknativity.org.

Some childhood memories are tethered to the present like a docked boat. I live a short distance from the lake I swam in as a child, and I can stand at the shore today and easily bring up the feeling of floating on my back in cold currents while my 9-year-old eyes squint in the July sun. But other past events feel a lifetime away, with memories small at the horizon. I need effort to draw them in.

This was true when I heard the news that Black Nativity, Boston’s gospel-song play written by Langston Hughes, would be celebrating its 50th season this December. First, it struck me as both an astonishing accomplishment and a foregone certainty. Black Nativity is a steadfast institution, telling year after year the story of the birth of Jesus through music, dance, the Gospel of Luke, and Hughes’s own poetry. These shows have been woven into holiday rituals for tens of thousands of families since 1970.

Photo Credit : Hakim Raquib

I live in rural New Hampshire, and the six formative years I spent as a Black Nativity cast member felt dim and far away. So I went on a search for touchstones to connect me back to those important memories.

I did not have to search long. My mother reminded me I’d first seen the showat age 5. “You just wanted to dance in the aisles the whole time,” she said. And it came back to me: the popping, layered rhythm of African drumming that echoed the intensity of Mary’s birthing pains as she danced the dramatic peak of the show. The original drum score created by late Nigerian musician, educator, and activist Michael Babatunde Olatunji has been a soul-shaking feature since its inception. Recently I listened to a recording of the 1995 show, and the voices still raised the hair on my arms.

When I was a teenager, I saw Black Nativity in the Tremont Street Baptist Temple. “The Dialogue: What Child Is This?” was beautifully arranged as a duet by the show’s original music director, John Andrew Ross. The song’s slow, pronounced bassline stood in spare contrast to the rocking, jubilant numbers. The stage was completely dark except for the spotlit faces of Black Nativity veterans Janice Allen and Alda Marshall, who sang that night. I had little religious education, but the performance moved me to tears. That night I decided to become a part of the tradition. After the show I told my mom, “I want to sing that song next year.” It was the biggest goal I’d set in my life.

* * * * *

Edmund Barry Gaither, the executive producer of Black Nativity, was there when John Andrew Ross first brought the idea of doing the show to Elma Lewis, who later became Black Nativity’s artistic director. The show has been produced in many venues over the years. Its current home is in downtown Boston, at the Emerson Paramount Theater on Washington Street.

On a recent Zoom call with the production team, Gaither talked to me about what Black Nativity represents. “A tradition is property that exists with an energy you become a part of; you join it. Black Nativity is the property of Boston’s Black community. It is available to men and women of goodwill everywhere. And it also confers an obligation—you are joining something you’ve got to live up to once you step into it.”

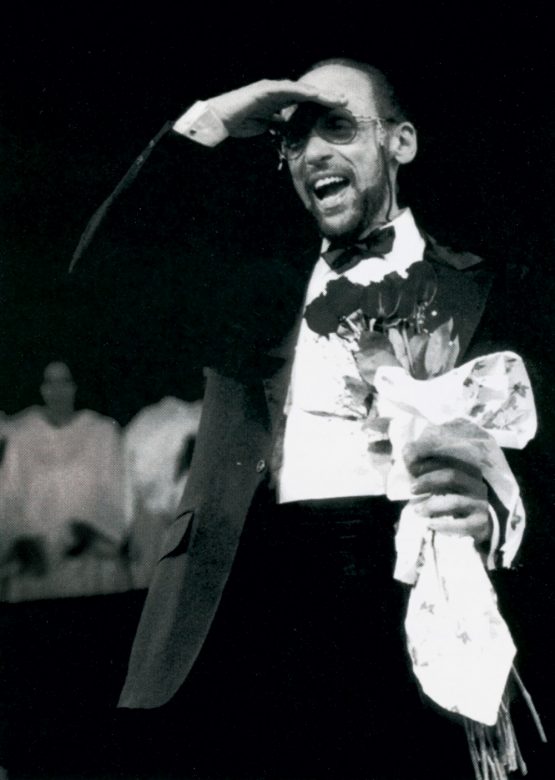

Photo Credit : Courtesy of the National Center of Afro-American Artists

In October 1993, I stepped in. My mother brought me to the basement of Eliot Congregational Church in Roxbury, where the auditions and rehearsals were held. Returning performers greeted each other like family and gathered to revisit the score and teach new members. The 75-plus people who made up the cast were a mix of professional and amateur singers from across Greater Boston. Our ages ranged from 6 to over 60.

I was 16 and warmly welcomed by women who had been there for years. They told me where to stand and made sure I had the sheet music. The show’s “stage mothers” are the support team that ensures everyone is fed, bobby-pinned, disciplined, hugged, and encouraged backstage. They are indispensable communal glue.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of the National Center of Afro-American Artists records at Northeastern University’s Archives and Special Collections

It was a nudge from a motherly mentor that gave me the courage to approach Mr. Ross and audition for the soprano solo in “The Dialogue.” I had prepared for weeks but still felt jittery as I walked to the front of the room and stood rigid by the piano in front of everyone. When the last note faded, Mr. Ross sat for a moment, then said, “You deserve to sing that part, and the audience deserves to hear you.” When I asked him who would sing the duet with me, he said simply, “It shall be revealed to you. You may go back to your section.”

I didn’t realize at the time that the part I auditioned for had always been sung by adults. Encouraging young people to stretch and build confidence was a founding principle instilled by Elma Lewis, the show’s co-creator. “She made sure the children learned important lessons. It was a training. They could do extraordinary things if they had the confidence in themselves,” Gaither recalled.

Elma Lewis passed away in 2004, followed by John Andrew Ross two years later. They had been iconic fixtures for decades, synonymous with the show. The vacuum of energy created when charismatic leaders leave their posts often means the creations cannot stand on their own, but Black Nativity’s engine still runs, reliable and strong.

Photo Credit : Idly Galette

Milton Wright, the current musical director, told me why the show remains vital. “We bring authenticity. Gospel in itself is a genre that highly appreciates personal adaptation.”

Betty Hillmon has worn many hats in Black Nativity since joining the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts in 1975. “It is an open show for the cast,” she told me. “And the role that is most popular among the children is Mary. In their minds they can do that dance—or any solo. They are preparing themselves, and we don’t tell them that they can’t.”

“We have retained the best features, and everyone brings their artistic genius,” Gaither added.Many of the children who grew up performing in Black Nativity want the same experience for their kids. Kafi Meadows, the co-chair of Black Nativity’s 50th anniversary celebration committee, has a daughter in the show. “She pushes herself,” Meadows said. “The growth is good for children. It’s an opportunity for character development.”

Photo Credit : Idly Galette

After we said good-bye on that Zoom call I sat in front of my dark computer screen. I could grasp once again how those early years on stage had shaped me. The sense of self that I gained had never gone away. And if I ever wanted to step back in, I have a permanent place in that tradition. I may move to the alto section, since my voice has changed, but there will always be a robe for me. The disconnect I’d felt from those memories spoke more to my challenges in trying to find that feeling of community here in New Hampshire. Black Nativity evokes feelings of being seen and accepted in ways that are much harder to practice where I live now.

I remembered the first time I carefully stepped out from the chorus to the front of the pitch-black stage to sing my solo. My bare feet were cool on the floor of the cavernous old temple on Tremont Street. I lifted my head and squinted when the bright spotlight hit my face.The expansive feeling was familiar—not like floating, but like being held and carried, supported at my back. It was the feeling of being connected and alive, at home in my skin.