The Yankee Interview: The Joke’s on Her

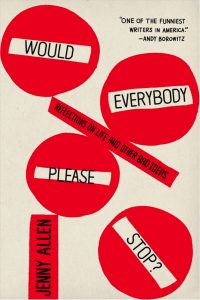

Jenny Allen tells stories. Really funny stories. For years as a journalist, she told other people’s stories—people like Sam Shepard, Arthur Miller, Katie Couric, Sally Field, and Martha Stewart. Now she’s telling her own, whether it’s onstage, writing for The New Yorker, or in her new collection of personal essays, Would Everybody Please Stop? Allen […]

Writer Jenny Allen

Photo Credit : courtesy of Jenny AllenJenny Allen tells stories. Really funny stories. For years as a journalist, she told other people’s stories—people like Sam Shepard, Arthur Miller, Katie Couric, Sally Field, and Martha Stewart. Now she’s telling her own, whether it’s onstage, writing for The New Yorker, or in her new collection of personal essays, Would Everybody Please Stop? Allen finds absurdity, beauty, and humor in almost every situation, including her own bout with ovarian cancer, which inspired her award-winning solo show, I Got Sick Then I Got Better. Now a full-time resident of Martha’s Vineyard, she recently chatted with us about her strong New England roots, where she finds her material, and what’s next for her career.

Photo Credit : courtesy of Jenny Allen

You’re a native New Yorker, but you have a deep connection to New England. When did that begin?

I spent every summer until I went to college in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom. There are pictures of me as a toddler on the lawn of my grandmother’s home in Craftsbury Common, which is a beautiful little town. It’s so pretty that Alfred Hitchcock featured it in The Trouble with Harry—I guess the contrast of shots of a pristine town against whoever got murdered was irresistible to him. Anyway, it’s indelibly etched in my mind as an idyllic place. Maybe it wasn’t, but the New England aesthetic was, with the big town square and the huge common, a green lawn surrounded by a white fence, with a beautiful congregational church. The church I sometimes go to here in Martha’s Vineyard looks exactly the same as the one I went to in Craftsbury Common. There are so many architectural similarities. That’s why I feel at home here.

What was your grandmother like?

Margaret Allen was quite a character, a very bold, creative person. She was a free sprit who made her own rules, or a less flattering description would be that she never thought the rules applied to her. She lived a proper lady’s life in Scarsdale, with a husband and two children, until her husband died very young, in his 40s. She became a full-time piano teacher, and after a brief marriage to one of her piano students—which did not go over well in Scarsdale—she eventually moved down to Berea College in Kentucky and became a professor of humanities, where she taught for 40 years.

She was famously frugal—she’d tear a stick of Beemans licorice gum into two pieces to share, and we’d reuse paper napkins for a week—and she was very good at amassing money. She bought a beautiful summer home in Craftsbury Common … [but] since my grandmother hated idleness and liked being busy, even in the summer, she opened the Kentucky Shop in her home and I worked there every summer.

The Kentucky Shop in Vermont?

Most of the Berea College students were the Appalachian poor. Their tuition was free but in return they had jobs to help sustain the campus, including a serious crafts enterprise where they made exquisite wares, like beautiful woven goods and wooden toys. My grandmother sold their goods out of her home, and she was very proud the proceeds went back to the college…. My job was to wrap presents and tally the sales. It was a big honor to work there. People still remember the shop, this place where their mother or grandmother took them while they were on vacation.

What did you do when you weren’t working at the shop?

While my grandmother would have been difficult to have as a mother—she was always the main event—as a grandmother, she was a lively character. She gave us piano lessons and she wrote plays for us to perform on the lawn. We’d put on little costumes. She loved performance.

Do you think that’s when the seed was planted for your creative work?

Yes! Those summers were really, really fun. She held music workshops, and she had a whole creative theory—which may or may not have been crackpot—called “creative motion,” which focused on music and movement. She had acolytes and self-published books about it. The theory had to do with springing your diaphragm. If we were slumped over at the dining room, she’d say, “Spring your diaphragm!”

And there were these characters who lived in the area. One was Miss Jean, who was a friend of my grandmother’s. She built a wonderful library next to her house. If my grandmother’s thing was her shop, Miss Jean’s thing was her library. It wasn’t the town library, it was Miss Jean’s library, and we’d all go over there—a heavenly, snug, wonderful place. Every summer Miss Jean staged a Shakespeare play, and during the Old Home Days parade she would ride in a chariot wearing a toga and a laurel crown to advertise the play. My last year there, I was in her production of Hamlet. Miss Jean was Hamlet and I was Laertes, and Miss Jean was so old she couldn’t remember any of her lines, which made it hilarious and scary. But it was always thrilling to see Miss Jean in her chariot.

There’s some wonderful synergies here, because you now work at the Martha’s Vineyard Playhouse.

I do help out wherever I can, but mostly I’m a kind of literary manager. I read play submissions and recommend which ones that MJ Bruder Munafo, the artistic director, might want to consider—mostly for our Monday Night Specials, a staged reading series that we do every summer…. We also produce three to five plays a season, and I confab with her about those as well.

And I’m working on a play right now, which will use some of the humor pieces from my book [Would Everybody Please Stop?] that lend themselves to monologues.

Tell us a little about the book.

Tell us a little about the book.

It’s a collection of humor pieces and personal essays … [that] go from very silly to poignant. The personal essays speak from a point of loss, like experiencing health issues and navigating life after children and marriage. All of them—except the piece about Elmer Fudd—are loosely from the perspective of a woman who’s hit some potholes driving through life.

Are you that woman?

Well, the humor pieces are a version of me, if you turn the kaleidoscope a little bit. She’s a slightly more nervous and crankier version of me—she’s me at my most flailing-around. For instance, I love Buddhism and meditation, but the me in the book can never get meditation right. She thinks that mindfulness is when you sit down, calmly breathe in and out, and right then in the present moment rack up all the terrible things in your life that might happen—especially the ones you don’t know are happening—so that when they do happen, you’ll be prepared.

In the humor pieces, I’m being driven more crazy than I actually am in real life, but successfully coping with things isn’t as funny.

Andy Borowitz included you in his book The 50 Funniest American Writers. How do you approach writing humor?

For me and my humor, the joke has to be on me. I don’t often write about politics, and I don’t have a great imagination, so my writing’s usually grounded in what’s going on around me—domestic things that befuddle and bewilder me, like living in an old house and having things fall off it all the time. Or how the garden turned out. I wrote a piece about my garden for The New Yorker. My cucumbers were microscopic, the size and shape of cashews. It was really hard to look at them—they were like those tiny infants who suffer from failure to thrive. I felt like I’d failed them.

And if you’re writing about a woman of a certain age, it’s the same in New York as it is in Martha’s Vineyard. For instance, when I flirt with men I try not to enumerate my health issues, but I wrote a piece about trying to flirt with someone at a wedding, and my so-called persona, the exaggerated me, thinks she’s being cute and beguiling when really she’s talking about her acid reflux and her approaching deafness in one ear. Basically, she’s driving this man away. I’ve had a couple of men detail their physical aliments to me over coffee dates, and I think they made a mental note of “not a great idea to do that.”

You write mostly monologues. Why?

I ask myself the same question. I don’t know why that is. It seems to be what I hear in my head. I’d love to write a full-length play, but I can only hear one voice in my head right now—that’s not exactly true, but mostly I just hear one voice. Maybe this is a release from years of expository writing, where I was the omniscient narrator. I got tired of reporting. I might return to it, but something in me wanted to write monologues, to do something different that excited me. Maybe after all those years of reporting, I needed a voice.

What stories do you still want to tell?

That’s a great question. I really want to find a way to talk about my mother, who was a difficult person. I’d like to say I came to enjoy her company, but I never really did. Those of us who have difficult parents love them, but they make it hard for us to do so. I felt that I was able to tell her as she lay dying that I loved her and I meant it, but she was difficult right up to the end. I wish there were a sweeter story to tell and that I could find a way to tell that story.

I also want to write more stories about moving from a comfortable 35-year life as a city girl in NYC to a different locale. To tell more stories about a woman of a certain age—I don’t know why I keep saying that phrase—who’s been in some ways quite spoiled, and made assumptions about how her life would continue in a particular socioeconomic bracket, and then that’s not true anymore. And I’d like to make good on something I’ve taken notes about for years, to write about the ongoing search for a life of the spirit and a way to live that reflects that. The woman in my pieces—the cranky, bewildered, anxious character—lives inside me, but so does the person who wants to live with peace, equanimity, generosity, and a loving spirit. Those things are not always compatible with humor.

For more on Jenny Allen, go tojennyallenwrites.com. You can also see her onstage this year in Deb Margolin’s Imagining Madoff at 59E59 Theaters in New York.