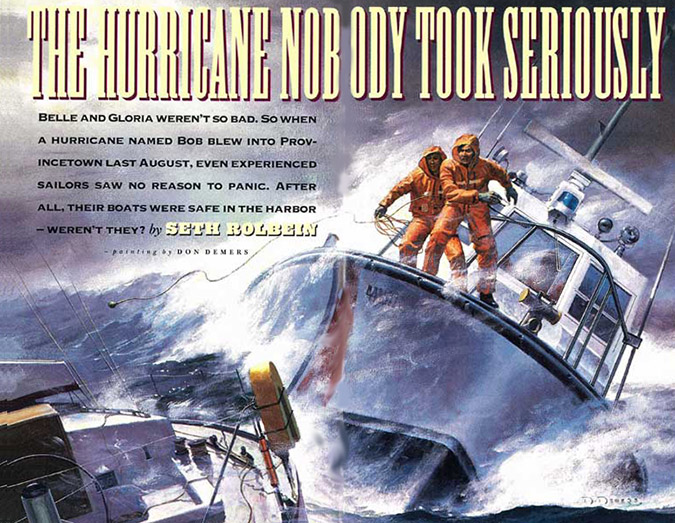

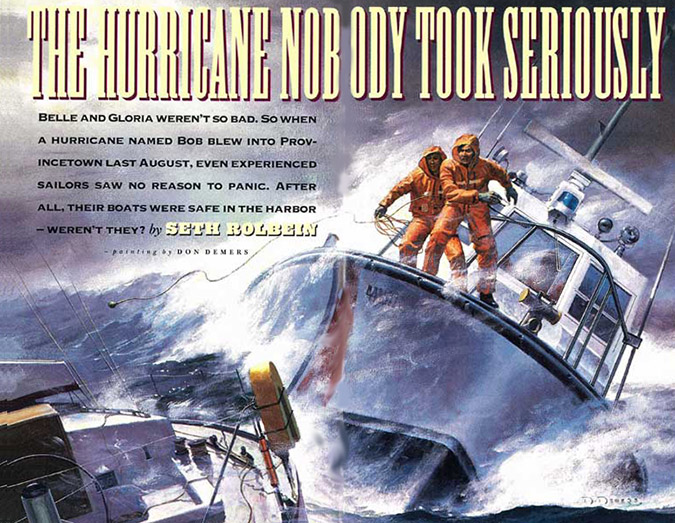

Hurricane Bob: The Hurricane Nobody Took Seriously | Yankee Classic

1991’s Hurricane Bob wasn’t much of a storm. But to four Coast Guardsmen in Provincetown Harbor, it was nine hours of sheer hell.

Belle and Gloria weren’t so bad. So when Hurricane Bob blew into Provincetown on August 19, 1991, even experienced sailors saw no reason to panic. After all, their boats were safe in the harbor – weren’t they?

Excerpt from “The Hurricane Nobody Took Seriously,” Yankee Magazine, August 1992.

Even some of Provincetown’s saltiest characters didn’t take the threat of Hurricane Bob all that seriously.

After all, Provincetown Harbor is one of the safest anchorages in New England, sheltered on the north and west by the spiral arm of Cape Cod and on the south by a barrier beach called Long Point, its inner harbor guarded by a granite breakwater that would cut the legs out from under any wave that might manage to get past the natural sentries.

What’s more, Boston weathermen always predicted disaster. Gloria had been the last hurricane to pass through, Belle before that, and if everyone had believed Boston weathermen back then, all of Cape Cod would have run for the White Mountains. Sure, both storms had huffed and puffed, but they hadn’t blown the house down — or the boat off the mooring. There had been too many windy wolf cries in the recent past to get panicky about Hurricane Bob.

Which made what four men on one 44-foot Coast Guard patrol boat faced on August 19, 1991, in what was supposed to be the security of Provincetown Harbor, that much more remarkable, destructive, and dangerous.

Ken Cope, boatswain’s mate second Class, 24 years old, could tell his crew was nervous — maybe excited was a better word — from the tone of the talking and joking as the cards went down for a game of spades. But he felt pretty comfortable. He had two full packs of cigarettes, so that was all right. But more important was his training, only six months earlier, at the Coast Guard’s National Motor Lifeboat School off the Washington coast, which teaches coxswains how to handle heavy weather and surf. Perfect training for a hurricane. He was the natural choice of the station’s officer in charge, Bill Curtis, to take the wheel of the 44.

Looking around the table, he liked what he saw. Dean Demers, 23, machinery technician, five years in the Coast Guard, was the boat’s engineer. After a year running together, Cope knew that Dean was experienced, resourceful, and cool under pressure. Seaman Matthew O’Malley, 19, had also served with Cope for a year, so he knew the ropes — although he was bunmed out about his canceled leave. The fourth was Seaman Apprentice Kevin Yalmokas, also 19, new to the crew, in the Coast Guard since April. Seemed solid; everyone called him “Yak” because of his last name, not because he was a big talker.

And of course there was a fifth personality to consider: patrol boat 44397. At 20 she was older than two of the crew. Of the station’s two boats, this was the one for heavy weather, no doubt about it. The 41-footer was faster, but the 44’s twin engines 185 horsepower apiece, gave her muscle to burn, left a deep V wake wherever she went. Part of the reason she managed only 12 knots was that her steel hull had been made even heavier by lead ballast down below; if she ever flipped in heavy seas, the weight would quickly right her again. She could handle 50-knot winds and 30-foot swells.

By 9:00 A.M. the four crewmen had helped tape the station’s windows at the west end of town and battened down what could be secured ashore. Then they motored a quarter mile into Provincetown Harbor to put the 44 on one of the Coast Guard’s heavy-weather moorings — standard policy with the station on full alert, Condition One. All 37 Coast Guard stations from New Jersey to Maine were doing variations of the same thing. Bigger Coast Guard boats had run to the open seas, a safer place for a large vessel to ride out bad weather than anywhere near the dangerous shallows. Smaller boats had moved behind hurricane barriers like New Bedford’s or into the safety of the Cape Cod Canal.

Cope and his crew expected to ride out Hurricane Bob bouncing around their mooring, with a safe fish-eye view of the storm. Yet Officer Curtis insisted that the crew of the 44 pack 24 hours’ worth of provisions and carry a portable radio to back up the regular communications system. Cope and his crew thought that kind of extreme, although of course they did it.

By 9:45 the winds were at 35 knots, and the card game was suspended; the crewmen, wearing their orange Mustang suits and heavy-weather harnesses, were on deck watching what was, for most of them, their first hurricane at sea. The first call came in: Flyer’s Boatyard, a neighbor of the Coast Guard station in the west end of town, had been working feverishly to pull as many boats as possible from the harbor. But a bunch of floats still bobbed around. John Santos, whose family has run the yard for decades, knew he had to get them to a safer spot, and the far end of the harbor, tucked up against Long Point, seemed like the best place. He had strung the floats together, towing them with two outboards through the rising chop when an engine sputtered and died.

Bad timing, worst case. But this was the kind of work the 44 was built to do; 35-knot winds were well within her range. Cope ordered the boat off the mooring. The crew attached a towline to the front of the makeshift caravan of floats. Cope agreed that the lee of Long Point was the best place to hide. Approaching the shallows, he built up speed and then released the towline. “We kind of slingshot them up onto the beach,” he said.

Cope swung back to his mooring, snagging the line to tie up. The cards waited, but this was one game that would never be played out. The radio crackled again: The Golden Dawn, a Maine fishing boat taking shelter in Provincetown Harbor, called to say she was taking on water.

The Golden Dawn sat at the edge of the inner harbor, east of the Coast Guard mooring, less than a mile away. It was tight quarters, with dozens of boats crowded into the protection of the granite breakwater. Cope was glad for his recent training. He remembered to use engine power to help steer, to back one engine and rev the other for tight turns, to drive rather than pivot, simple techniques made possible by two powerful throttles. Dean Demers prepared a pump and made ready to board the fishing boat as they approached, when a new version came back: “He’s not taking on water, he might be taking on water’,” Cope heard on the radio. In the howl of the rising wind, the 44 tossing, Cope looked around angrily. The fishing boat’s battery was dead and needed a jump start, actually, which the Coast Guard could not provide. This was not a life-threatening situation. The 44 turned and fought her way back to the mooring, leaving the Golden Dawn on her mooring inside the breakwater.

In just the 20 or 30 minutes needed to reach the Golden Dawn and return, Cope realized that the winds had doubled to 70 knots. Bob was arriving. Now would be the time to tie up and ride him out, like every other Coast Guard boat in the Northeast was doing. But in Provincetown, it would be different: The Bay Lady II, over 80 feet long, a strikingly handsome steel-hulled boat that offered summertime harbor cruises, was too big for her anchor and mooring. Slowly, inexorably, Bob was pushing her toward the beach, toward a jutting pier, toward a score of other boats moored in her path. On board, the owners called for help.

Cope was willing, but it was Officer Curtis’s call. Do what you can, Curtis told him. “We don’t run away from problems. That’s not why the Coast Guard is here.”

The Bay Lady was close by, on the western side of the harbor. Cope tried to position the 44 as close as possible, fighting chop at every turn, while Demers waited for the right instant to heave a line. Heaving a line across 70-knot winds is not something that can be practiced. Cope jockeyed the 44 to within 25 yards, and Demers hurled the lightweight messenger line; it was a perfect throw, wrapping itself snugly around a stay on the bigger boat. “Beautiful!” Cope yelled to his engineer. “That’s beautiful to see.”

They played out 200 feet of the heavier towing line and started the tow, a 44-foot boat trying to drag an 82-foot boat across hurricane-force winds. “We made all of one knot moving across the harbor,” says Cope. Demers, positioned to the stem, heard the line under so much stress that it was growling, barking like an angry dog. Yet it was holding — so far. The shallows in the lee of Long Point, the same place Cope had taken the floats, was the only place the Bay Lady might be able to anchor. Slowly, the 44 pulled her burden across the harbor. As they neared the point, Cope checked his fathometer to see how much water they had underneath them. No reading. The bottom was churning violently, sand swirling to the surface, blinding the equipment. He made his best guess, got the Bay Lady tight into the lee, and ordered his men to stand by while the sailing boat tried to anchor. As they watched, it was clear their work would be for naught: The Bay Lady was too big, the anchor too small. The boat already was being pushed back across the harbor toward Provincetown.

“There’s nothing left we can do with the boat,” Cope yelled to the Bay Lady’s skipper. “We’ll take you off if you want.”

No, the skipper would stay, unhappy that the Coast Guard wouldn’t. “It was a decision I had to make and live with,” says Officer Curtis, who was monitoring the action by radio. More distress calls were starting to come in. “For the rest of the people in that harbor, it was the best decision.” The Bay Lady, pushed back toward shore, drove aground. She was damaged, but her hull was intact — and she avoided crashing into other boats, avoided the potentially deadly piers jutting nearby.

Freed from his tow, Cope tried to get his bearings. It was not yet noon, but in less than an hour, the face of Provincetown Harbor had changed almost beyond recognition. Dense mist and fog reduced visibility to 20 feet at best. Mean, sloppy chop reached eight to ten feet; the 44 could handle rollers much higher, but this stuff was without rhythm, unpredictable. Gusting past 100 miles per hour, the winds far surpassed what the boat was rated to sustain.

Cope ordered his men to clip their harnesses into the D-rings located all over the boat to prevent them from washing overboard. “Hey, Yak,” Matt O’Malley screamed into the wind, talking to the apprentice seaman. “You better be hooked up good, because when we roll over, I want you to be here when we come up.”

“I’ll be here,” Yak called back.

Waves slammed into the hull, washing over the deck. Both the secure and standard radios on board took water and shorted; the crew could hear calls on Channel 16, but could not respond. The portable radio that Curtis had insisted they carry became their only voice out.

Cope heard on 16 that the Miss Lisa, another fishing boat, had broken loose behind the breakwater. She had no steering and could not keep from ramming whatever boats were in her way or dashing against the granite meant as protection. Curtis ordered the 44 to respond.

Again they fought east, bucking surges and chop to find the Miss Lisa. She was ghosting toward a dozen or more boats moored in her path. There was little time. Demers heaved the line, hitting his target on the first cast. No 200 feet of line this time. There was no room to let the Miss Lisa swing wide. They kept her tight on the hip, the twin engines of the 44 straining, the line taut and vibrating. Cope knew there was a big green mooring ball on the far side of the breakwater that could hold a fishing boat this size. They came alongside and snagged the ball, tying the Miss Lisa down. She would ride out the storm safely.

Exhaustion was setting in. Cope felt the strain, knew his crew could too. He hadn’t smoked a single cigarette or had one cup of coffee since they boarded that morning. Now, at midday, Bob was at his howling height. Cope steered for the inner harbor, looking for any available shelter. Then engineer Demers heard the one sound he prayed not to hear that day: the alarm bell signaling trouble in the engine compartment.

Seconds later, the port engine cut out. Demers wrestled out of his restraints and went below. As he passed through the crew quarters, he noticed that the cards from the game of spades were scattered all around. He opened the door to the small engine room. The engine wasn’t turning over. Nothing at all. He knew he had to do something fast, but the wild gyrations of the boat were bouncing him around, hampering his ability to work. As the seconds passed, Cope, at the wheel of his crippled boat, fought a rising panic: Without both engines, he could not maneuver in this hurricane.

Cope could see next to nothing in the mist, but he knew he was near other boats, near the breakwater. He looked at the radar to get a fix on his position, but the screen was blank. The wind had ripped the radar equipment off its mount, leaving Cope blind.

Demers ran back up on deck to tell Cope he couldn’t restart the engine. Get the anchor overboard, Cope told his crew. He knew it weighed 60 pounds and ought to hold, even in this chaos. What he didn’t know was that the metal pipe designed to hold the chain and feed it off the bow had broken, binding the line in place. The anchor was jammed.

Cope stood at the wheel, feeling a helplessness he’d never felt on duty before. He suddenly realized that he and his crew could die in Provincetown Harbor.

“Prepare to ground!” Cope yelled. “Strap in! We’ll try to make a controlled landing on the beach!” Now Cope found himself in the position of the boats he had been trying to help — except, of course, there was no Coast Guard to call.

Demers had run back below, trying to feed out the anchor chain, a futile effort with the anchor pipe busted. The open door to the engine compartment was slamming open and shut. He went back to the port engine one last time before following his coxswain’s orders and tried the mechanic’s last resort: He kicked the starter. “It popped back,” he remembers, “and the engine started. Believe me, that made my day.”

Back in control, muscling the 44 toward the inner harbor, Cope spoke to O’Malley. “I’ve found my limitations,” he said. “It’s a hurricane.”

The fog lifted long enough for them to look around. Finger piers were breaking apart, debris was smashing hulls. Shingles from the roof of the fish-packing house filled the air like shrapnel. Demers watched in fascination as the three tall masts of a big sailing boat toppled like trees.

The wind veered from south to southwest without diminishing. The breakwater, now end-on to the wind, no longer caught the biggest waves, which had a mile of open water to build on. Even in the small spaces between piers, the chop was at ten feet. This was no place to rest. Cope headed back out.

Dozens of boats, large and small, had ripped off their moorings. Sailboats careened across the harbor at eight knots or better under bare poles, with no one on board. The Miss Sandy, a well-known Provincetown fishing boat, had parted a line at the wharf and was swinging, not yet loose. Cope positioned the 44 against the Miss Sandy, trying to muscle her back into position, relying on locals who had braved the winds and were standing on the pier ready to tie her down again. Suddenly, they screamed for the Coast Guardsmen to turn around: The Golden Dawn, the same boat that had called for help before Bob truly arrived, was running free behind them, a 65-foot domino about to knock down a score of boats that lay in its path.

Once again Demers had to heave a line, and on the second try he got it to the rampaging fishing boat. Cope pulled her in tight behind the 44.

“Where do you want to go?” Cope screamed to the Golden Dawn’s crew. “Which beach do you want to land on?” The shrieking wind drowned their answer. “Finally, I figured to hell with it,” he remembers. “We moved west and put him on our mooring. We figured there was no way we were getting back to see it.”

One Provincetown native, Jimmy Costa, who was on the waterfront trying to protect his own boat, couldn’t believe what he was seeing: “That dragger [the Golden Dawn] was sideways to all the other boats in the area. If the Coast Guard hadn’t come, grabbed him, and pulled him out of there, he would have taken some stores on Commercial Street out, let alone the boats.”

After securing the Golden Dawn, Cope turned east. Todd Motta, a Provincetown fishing boat captain, was in trouble on the Liberty Belle. Like many, Motta had figured he could ride out the storm tied to the wharf. But his wooden hull absorbed a pounding from other boats tied alongside. When Motta released his lines to try to run out of the harbor, debris (probably from a lobster pot torn free) fouled his propeller and stalled his engine. Motta was drifting toward the beach. He managed to plant three anchors in surging shoal water, but he was taking a beating. Cope swung around the wharf and pulled nearby. Compared to some of the heaves Demers had made that day, this one was a piece of cake. Cope towed the Liberty Belle to a safe spot beside the pier.

“What do you need?” Motta shouted to Ken Cope.

“A cup of coffee,” Cope shouted back. He could see his hands shaking from fatigue. But he could also see, with relief that felt even better than coffee, that Bob was laying down. The hurricane was as fast moving as it was intense. It was eerie, almost supernatural, how quickly the winds were dying. They had dropped back to 35 knots, calm enough for another game of cards.

Cope had lost track of time. When he looked at his watch, it read 6:00 P.M. After nine hours of brutal pounding and fierce concentration, he and his crew were physically and mentally exhausted. Slowly Cope eased the 44 away from the wreckage downtown and motored back to the Coast Guard pier.

The magnitude of what they had been through wouldn’t become apparent until the next morning: Of the estimated 150 boats in Provincetown Harbor, 38 had sunk on their moorings. Another 45 boats had broken free and beached along the shore.

Two factors, one natural, one human, kept the toll from being much higher. As luck would have it, Bob struck during low tide, saving a great deal of property from much worse damage. And Officer Curtis had ordered the Coast Guard 44 off its mooring with a solid crew on board.

As reports from around the Northeast came in, it was soon apparent that this small boat may have been the only Coast Guard vessel active during the hurricane. Without doubt, Ken Cope and his crew recorded the most rescues performed anywhere on the coast that day.

“I’ll tell you, I’ve never seen anyone work that hard retrieving boats,” says Jimmy Costa, who watched from the shore. “It’s amazing they did what they did in the conditions they were in. I could see the bottom of their boat at times, I could see his paint job, I could see his propellers coming out of the water. They were right on their side. Just to maneuver, let alone tow, is unbelievable. I don’t know how those guys were working lines. They saved an unbelievable amount of money and grief. I’m still shocked nobody drowned.”

“The crew kept me together,” says Cope. “They performed perfectly. I couldn’t have asked for any more. Even when the anchor wouldn’t come out and the engine wouldn’t start, they didn’t panic. But I’ll tell you, that’s nine hours I never want to do again.”

Excerpt from “The Hurricane Nobody Took Seriously,” Yankee Magazine, August 1992.