Curious About George | George Washington in New England

Separating truth from legend proves tricky when you follow in George Washington’s New England footsteps.

A portrait of George Washington graces the wall at Ye Olde Tavern in West Brookfield, Massachusetts, where—as the man’s own diary confirms—he stopped for a bite during his 1789 tour of New England.

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

George Washington is a terrible person to take a road trip with. The conversation is stale, to say the least, and when he does speak, he tends to be a little judgmental. It’s like driving cross-country with a particularly dour father figure, which is exactly the vibe he’s going for.

Washington may be dead and buried, but his words live on. His four-volume diary is available at most public libraries. If you stack the whole thing on a desk, it resembles a foot-high tower of burnt toast and reads about the same. It’s mostly a day-to-day catalog of where he had dinner.

But for history-loving Yankees, there’s one delectable bit near the end. Between October 15 and November 13, 1789, the same year he was first inaugurated, Washington embarked on a rambling tour of New England. His diary from this stretch forms an irresistible travelogue of a New England that has long since faded into history. I couldn’t help but wonder if there was something of it left, though. If I looked hard enough, could I find some trace of his footprints and walk in them? So, with his words as my guide, I hop into my car and head out to glimpse New England through the sage, hypercritical, and sometimes downright curmudgeonly eyes of George Washington.

—

“The Road between these two places is not on the whole bad (for this country)….”

—G.W., October 17, between Fairfield and Stratford, Connecticut

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

Washington did not sleep at the Brookfield Inn. Paul and Melissa Puliafico, the current owners, make that quite clear. If he had, though, he likely would have had something to say about it.

Washington took a southerly route through Connecticut, passing through Stratford and New Haven before hooking north and visiting Hartford and Springfield. Along the way, he sampled the industry of the countryside and recorded brief, blunt opinions of its quality. In Stamford, he found the apples to be “rather above mediocrity.” In Hartford, the wool was “not of the first quality, yet.” In Wallingford, he thought the corn “but ordinary,” and in Rye, New York, the hogs were “large, but rather long legged,” whatever that means.

He gave the same treatment to the region’s accommodations. Fearing that if he stayed at private homes, his presence might be construed as an endorsement in some local political squabble, he opted to sleep only at public taverns (the Best Westerns of the day). And like everything else, he rated them. The Widow Coolidge’s in Watertown, Massachusetts, was “very indifferent.” At the Taft Tavern in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, “the entertainment was not very inviting.”

These critiques seem especially harsh given the circumstances. Washington didn’t plan his stops far in advance. Innkeepers were given little warning—so little, in fact, that when his party reached Brookfield, Massachusetts, on October 22, Mrs. Bannister, the proprietor, turned them away. As the legend goes, she had a migraine and refused to open the door. It was only later that she discovered who had been on the other side.

Today, the Brookfield Inn is a rambling affair, with additions built upon additions. Paul and Melissa have tied the place together with a colonial decor that is homey, if not entirely historic. They bought the property 30 years ago and quickly discovered they’d never be able to afford a full restoration. So they focused instead on returning to the building its dignity. “The room with the fireplace was neon green,” Paul sneers, gesturing to the lounge. “And it had a Formica bar!”

After striking out at the Brookfield Inn, Washington had pushed on to Spencer and stayed at Jenk’s Tavern (“a pretty good Tavern”). Melissa hands me “a snarky little poem” that someone in Spencer had written on the trip’s centennial. “We thank old lady Bannister/and will prize her memory,” the poem reads. “For letting our first President/try Spencer’s hospitality.”

The joke was on them, though: Jenk’s Tavern burned down years ago, as have many of the establishments Washington visited. The rest have either passed into private hands or become museums. It seems ludicrous, but there’s not a single inn in New England still operating that can claim, “George Washington slept here.” The Brookfield Inn is the closest. It proudly advertises, “George Washington almost slept here.”

The inn had subsequent brushes with presidential history. “Calvin Coolidge stayed here a number of times,” Melissa says. “We have a picture of FDR coming out the front door.” But it’s the Washington story that puts them on the map. They say a surprising number of guests ask about it.

The pair lead me to the oldest part of the inn, just two rooms wide. This, they tell me, is where George Washington would have slept if he had, in fact, slept here. Running down the length of the space is an original chestnut beam, which Paul is visibly proud of. He removed two ceilings to expose it, he boasts. “It’s hand-hewn. There’s no saw marks on it anywhere.”

One sturdy piece of history holding everything up. It’s a perfect metaphor for Washington, or at least how we like to remember him. In truth, our country has built on a thousand more annexes than this inn. The structural weight of it is borne across the shoulders of countless Americans—some celebrated, others forgotten. But because Washington went first, because he allowed his back to be the original foundation, we cherish that sacrifice more. Enough so that, 228 years later, history-minded tourists still knock on the door to see the place where Washington briefly considered sleeping, but didn’t.

“Does anyone come to see where Calvin Coolidge slept?” I ask Paul and Melissa.

“No,” they answer in unison.

—

“Finding this ceremony was not to be avoided, though I had made every effort to do it, I named the hour … for my entrance in Boston.”

—G.W., October 23, Worcester, Massachusetts

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

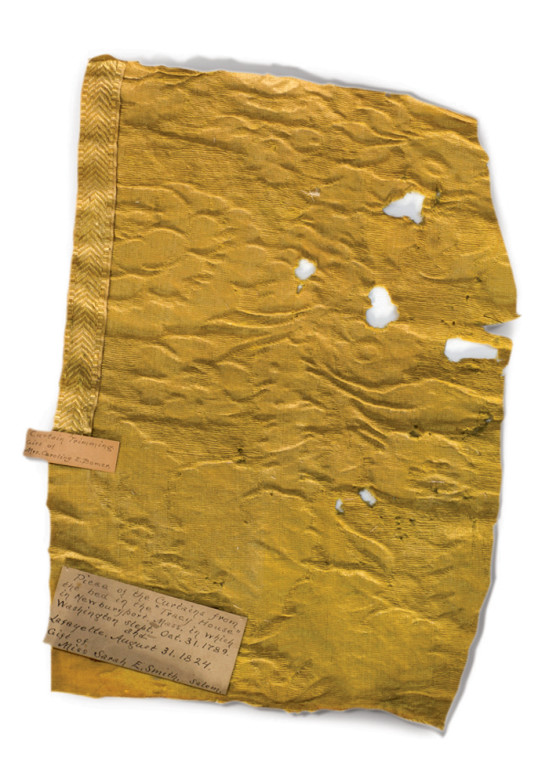

Katherine Chaison lifts the lid of the archival box and reveals her relic: a moth-eaten scrap of fabric dyed a particularly unpleasant shade of yellow. “If you just found this in a drawer, you’d probably toss it away,” she says.

Chaison is young, just seven years out of school, with long brown hair she wears over her shoulder. As curator of the Ipswich Museum in Ipswich, Massachusetts, she has inherited the question that has bedeviled generations of historians before her: What do you do with all these Washington mementos?

We think we know what fame is today, but we don’t. No American is likely to ever achieve the pinnacle of adoration Washington enjoyed during the first years of his presidency. On his tour, he was met by crowds at every stop. He couldn’t pass a village without the selectmen delivering an oration in his honor or firing off a 13-cannon salute. Judging from his diary, he didn’t enjoy it much. There are numerous references to his asking the local elders to tone down the hoopla a notch. They rarely complied.

The pomp and circumstance reached a head in Boston, where he was greeted with songs, poems, and a parade of the city’s workers. A decorative arch erected for the occasion bore the inscription, “To the Man who unites all hearts.” The weather was cold and damp throughout the festivities, but no one minded. The epidemic of sniffles that gripped Boston the next day was lovingly named the Washington Influenza.

At the time, the idea of a king—one perfect man standing above it all—was still hardwired into the American psyche. Whether Washington wanted it or not, following his miraculous victory in the Revolution, he filled that role. For a time, he could do no wrong.

His life became surreal. A gulf of enthusiasm opened up between him and the rest of the world. When he rode through a village, it was just another day for him. For those who saw him, it was the day they’d never forget. As a result, Washington developed an unintentional habit of dropping relics in his wake. Every cup that touched his lips had the potential to be revered for generations as a holy grail. Museums are lousy with such relics. I decide to spend a day on the Seacoast digging a few out of storage.

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

At the John Paul Jones House in Portsmouth, the curators show me a white woolen bedspread that Washington is believed to have slept under. Passing my hand over the still-soft weave, I ask how sure they are of the story. Did he truly touch this? They say they can place it in the home where he stayed at the time, but whether he actually used it is a matter of faith and legend. No one is swabbing these things for DNA, after all.

Across town at St. John’s Episcopal Church, the history is decidedly iffier. On the altar sit two regal red upholstered chairs. “One is a replica,” Sarah Hamill, the church’s archivist, warns me. “The other is the chair we hope George Washington sat in.”

The identical chairs were the seats of honor, and George Washington is known to have sat in one of them when he attended Sunday service at the church (then known as Queen’s Chapel). The problem is, no one noted which. In 1806, the original church caught fire and the parishioners only had time to pull one chair from the inferno. Was it the one Washington blessed with his bottom? Flip a coin.

In Ipswich, the yellow scrap is a fragment of a drapery from a bed Washington slept in. Years after the trip, the women of the town chopped it up and each took a piece. As with any other relic, it’s difficult to confirm the scrap’s authenticity—and even if it’s real, Chaison points out, there’s no guarantee he touched this part. “It could have been the canopy above everything. But there’s something about his presence that was enough to make this piece worth saving.”

She says mementos like this can be hard to interpret. The scrap says nothing about Washington’s life—it didn’t even belong to him—but it says volumes about the women who saved it. “It’s no different than the paparazzi or our obsession with celebrities today,” she says. “I think we all try to make meaning of our place in the world, and that’s what they were doing.” George Washington was the most important man on the planet. Just being close to him gave their lives a deeper sense of purpose.

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

Historians like Joseph Ellis have argued that this is why the other founding fathers recruited Washington to be the first president (his preference was to stay retired). The newly ratified Constitution was unpopular and people were not yet sold on the idea of being one unified country rather than 13 separate states. Washington’s advisers convinced him that if he lent his face and his fame to the government, he could harbor it through the fragile early years.

In that light, Washington’s laborious slog through New England makes more sense. It was a publicity tour for the nation itself. If he could turn a blanket into a golden fleece just by lying under it, perhaps he could get some of his star power to rub off on the idea of being American.

—

“The roads in every part of the State are amazingly crooked … and the directions you receive from the people equally blind and ignorant.”

—G.W., November 6, Uxbridge, Massachusetts

After a few days in Portsmouth, George Washington was ready to go home. His 57-year-old body had endured three weeks of travel by horse and carriage. He’d suffered enough for his country.

The strain of the trip is evident in his diary. His entries become shorter, his reviews more biting. He hits rock bottom after getting stuck in the hamlet of Ashford for a day because it was illegal to travel on Sunday in Connecticut.

“…my horses, after passing through such intolerable roads, wanting rest, I stayed at Perkins’ tavern (which, by the bye, is not a good one,) all day—and a meeting-house being within few rods of the door, I attended morning and evening service, and heard very lame discourses from a Mr. Pond.”

Photo Credit : Matt Kalinowski

When we call Washington the father of the nation, it conjures an image of some unimpeachable giant, but at moments like this we catch a glimpse of a different kind of father figure. Here is the father who lovingly endures. Here is the dad who sits through his child’s middle-school band recital, loathing every screeching second of it, but who still smiles and says “Good job” at the end, because he wants to raise us right.

I, too, have been on the road too long. I head home, making one final stop at Ye Olde Tavern in West Brookfield. As with everywhere else, Washington didn’t sleep here, but he did stop for a bite to eat. I do the same.

Inside, the lights are low. People mill around the bar, and a group of young Hispanic men are shooting pool and watching a soccer match on TV. Cindy Larson, the owner, meets me at the door and guides me through the dining room to a small sitting area at the far end. This, she says, is where he ate.

The rest of the building sports brand-new wood floors, but not here. During the renovations, Larson has been careful not to alter this room much, forbidding the builders to cut into any of the woodwork. “We’re trying to preserve as much as we can,” she says. “You should have seen them having to re-snake electrical wires without taking the wainscoting off.”

There isn’t a lot here, just two chairs facing a fireplace with a portrait of Washington above the mantel. On one wall hangs a shadowbox displaying all the different kinds of nails they found while removing the floors. There are modern staples and wire nails; triangular, machine-cut pieces from the 1800s; and a few handwrought nails that likely were here when Washington was. Seeing them all lined up, you can sense the long road of history separating him from now.

His legacy has taken some hits along that journey. He’s still revered, for sure, but historians today are just as apt to talk about his failures (his prodigious use of slave labor chief among them) as they are his successes. Even during his lifetime, he saw his star fade. By his second term, partisan newspaper editorials were depicting him as senile or, worse, a traitor to the Revolution.

Washington took it in stride. In truth, he may have been relieved to be humanized a bit; he never seemed comfortable sitting atop Olympus. If he were alive today to see how we remember him—the hallowed bedrooms, the sacred blankets, the mountain sculpted in his likeness—I’m sure he’d blush.

Washington never wanted as much as he was offered. Not taking it was his greatest gift to the country. At the end of the Revolution, some of his officers devised a coup to make him dictator; he suppressed it. At the end of his second term, reelection was assured; he walked away instead. Washington didn’t do the things he did because he wanted to be our first president. He just wanted to make sure he would be our last king.

Justin Shatwell

Justin Shatwell is a longtime contributor to Yankee Magazine whose work explores the unique history, culture, and art that sets New England apart from the rest of the world. His article, The Memory Keeper (March/April 2011 issue), was named a finalist for profile of the year by the City and Regional Magazine Association.

More by Justin Shatwell