Feeding Frenzy | Great White Sharks in New England

Sightings of Great white sharks in New England can lead to a boost in business for divers and great white shark enthusiasts.

With his crew on board their boat.

Photo Credit : Courtesy Stanley LarsenThe first onlookers? Locals mainly. Chatham, Massachusetts, residents who’d heard something from someone about something in the water. It was Labor Day weekend 2009, a beautiful late-summer day. They went to the sea, staking out a spot on the town’s wide, sandy beaches in hopes of catching a glimpse, maybe something better. Then the larger crowds came–eager masses of out-of-towners who claimed their own perches–twelve hundred steady regulars keeping watch at Lighthouse Beach alone. They snapped pictures, then headed into town to snap up the T-shirts and other tchotchkes that had suddenly appeared in local gift shops.

The media? They arrived in force, too, rumbling satellite trucks and roving reporters–36 news outlets in all, including the BBC–who gave this thing the whiff of Brad and Angelina. They jammed the phone lines and tracked down key officials; one enterprising journalist even showed up at the home of the town’s harbormaster at 10 one night for an impromptu interview. In this frenzied, all-too-familiar scenario–holiday weekend, prime sunny weather–everyone wanted a piece of the action.

Great white sharks can do that.

Photo Credit : FireflyProductions/Corbis

A little context. The file on unprovoked shark attacks is actually quite slim: worldwide, just 59 documented strikes in 2008. In United States waters there have been only 1,033 confirmed attacks since 1900, a scant six of them coming off the New England coast. In all, just 51 people have been killed by sharks in U.S. waters in the last 110 years, most recently a Florida kite surfer last February.

But that doesn’t diminish how much of a force of nature sharks–whites in particular–really are. The big ones are a showcase of almost mythical heft (up to 5,000 pounds) and ferociousness (a single bite can extract up to 50 pounds of meat). Written accounts of attacks go back as early as the mid-fifth century b.c., to the time of Herodotus, the Greek historian who wrote about Persian sailors who’d been eaten by sea monsters a generation earlier, in 492 b.c. It’s been 2,500 years of wonder and fear ever since.

“When I was kid growing up in Dorchester, [Massachusetts], we’d go swimming and everyone would always say, ‘Be careful–remember what happened to Troy,'” says Captain Tom King, creator of NewEnglandSharks.com, a Web site brimming with historical information about the region’s sharks and man’s interaction with them. “Troy” was Joseph C. Troy Jr., a 16-year-old Dorchester kid whose death in July 1936 is the most recent shark-related fatality in New England. He was swimming with a family friend in the late afternoon, about 150 yards off Hollywood Beach in Mattapoisett, on Buzzards Bay, when an eight-foot white shark suddenly latched on to the boy’s left leg, temporarily bringing him under. Just as quickly as it had appeared, however, the fish swam off, but not before striking a devastating blow. Troy’s leg, according to one newspaper report, had been “stripped of flesh from ankle to thigh by the razor teeth of the sea tiger.” He’d eventually made it to a hospital but had died several hours later as doctors were amputating the limb.

Before Troy, there was Joseph Blaney, a 52-year-old Swampscott, Massachusetts, fisherman who lost his life in July 1830 when a shark attacked his boat. As witnessed by nearby fishermen, Blaney’s vessel was pulled under, reappearing moments later without its captain, who was never seen again. “The sensation created at Swampscut [sic] by this melancholy event … is unprecedented,” reported the Essex Register.

Other stories endure, too: like the 12 days of terror inflicted on New Jersey beachgoers in July 1916, when a great white killed four swimmers and injured a fifth. That real-life tale later inspired Nantucket writer Peter Benchley, whose story of carnage on a small East Coast island in turn inspired film director Steven Spielberg, who then inspired a whole generation of Jaws fans. And on the small Massachusetts island of Cuttyhunk, west of Martha’s Vineyard, people still talk about the day in August 1954 when Charles Tilton and his son harpooned a great white and brought the giant dead fish to the docks for islanders to gawk at.

And on it goes: encounters and legends, awe and fear. The frontier may be gone, but sharks serve as a reminder that out at sea, an untamed wild of giants and death still looms. And so the masses descend on places like Chatham, for a glimpse of this mystery–to get a better look at something that’s not entirely understood.

One man whose job it is to understand is Greg Skomal, Ph.D., a 48-year-old marine biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and head of its Shark Research Program, one of the few state-funded programs like it in the country. Skomal, who lives and works on Martha’s Vineyard, matches a toothy, infectious smile with an inviting energy when the subject turns to fish. When the media need to know about sharks, he’s their man.

He first heard of the great whites off Chatham on a Thursday, an early-September day that found him in a windowless hotel conference room in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where he’d been waiting to lead a discussion on the state’s shark regulations, when his cell phone buzzed. On the line was Bill Chaprales, a longtime Cape Cod fisherman who’d worked with Skomal since 1992 tagging sharks throughout Massachusetts waters. Skomal had barely said hello when his friend, who was on his boat in Cape Cod Bay hauling lobster traps, cut him off.

“Two white sharks!” Chaprales burst out. “Two white sharks off Monomoy Island. George [Breen, a spotter pilot] just saw them.”

Skomal asked his friend to slow down. “When George lands,” Chaprales yelled over the roar of his boat’s engine, “just call him!” Then he hung up.

Skomal is no stranger to such calls. Part of his work involves sifting through the information that comes to him, and it’s not that uncommon for a report of a great white to make its way to his Oak Bluffs office from excited charter-boat captains, kayakers, lifeguards, and town officials. Most of such sightings can be chalked up to mistaken identity: basking sharks mainly, whose size, color, and shape resemble a white’s. But with Chaprales and Breen, Skomal knew he was dealing with solid information; both men have been instrumental in the success of his office’s research, which has amassed data on more than 24,000 sharks.

This is a field shaped by what isn’t known; data as basic as population estimates for many shark species are still a mystery. Little is known about where Atlantic whites winter, for example, or the routes they follow after they leave northern waters in mid-autumn. As of early September 2009, not a single Atlantic white had ever been successfully satellite-tagged–something Skomal, by his own admission, was more than a little obsessed to rectify. “I feel like Ahab,” he’d sometimes say. “My great white whale is the great white shark.”

Skomal knew he needed to get up in the air to verify the sharks himself, of course–preferably that afternoon. And if they were indeed great whites, he’d need to gather his tagging equipment, pull his team together, and get out on the water on the next good day.

Just before the meeting broke for lunch, Skomal spoke with Breen. “Yeah, they were whites,” the pilot said. “They were right up in the shallows off Monomoy Beach, in the same area you guys have figured they’ve been.”

For some time now, Skomal had been pushing the idea not only that a small number of Atlantic whites had made it as far north as New England but that these deep-water fish may have a reason to come close to shore. More than a decade of rapid expansion of the grey-seal population on Muskeget and Monomoy islands had introduced an easy and accessible food source, and with it, in recent years, a ratcheting-up of credible info from around Massachusetts: a small dead white washing up on Nantucket in 2008; two gutted seals found on a beach in Chatham in 2007; the sighting by a couple of Chatham beachgoers of a shark cutting a seal in half with a single bite in 2006. And, most revealing, a great white trapped in a saltwater pond and caught live on Naushon Island, off Woods Hole, in 2004.

By 2:30 Skomal was up in the air, crammed into a small single-engine plane, tucked behind Breen, the pilot, and clutching a point-and-shoot camera. Breen angled east, a cloudless sky overhead, the visibility nearly perfect as pilot and biologist approached Monomoy, south of Chatham. They stayed low, about 900 feet from the ground, so that Skomal could scan the water for shapes and shadows. In the distance he saw seals languishing on the rocks and in the dark-blue sea. Then, about a minute later, Skomal saw a long, wide body just a few feet under the water, its white underbelly apparent. Skomal yelled and leaned out the plane’s small door as he snapped away with his camera. Breen then buzzed up to Chatham and turned around to take another pass. On this second run, Skomal caught sight of an even more incredible scene: a loose cluster of five whites patrolling the water, most of them 15 feet or so long, none more than a couple of hundred feet from land. “There was no doubt what they were,” says Skomal. “I’m beaming. I’m slapping George on the back. I’m having the time of my life. What else could they be? It’s New England. Few fish ever get that big.”

No, they don’t. In the ever-changing environment that is the North Atlantic, where the clashing of the Gulf Stream and the Labrador Current creates a swirling mix of temperatures even in summer, the hospitality extends to only a small migratory number–blues, sand tigers, porbeagles, makos, threshers, baskers, and dogfish, predominantly–of the more than 450 species of sharks that rule the world’s oceans.

But that doesn’t diminish the importance of learning about these fish. And the most crucial research tool a marine biologist like Greg Skomal has at his disposal is the pop-up satellite tag, a $3,500 piece of technology that can help scientists piece together the story of a particular shark and its migratory habits over a period of several months. But its utilization requires a confluence of perfection.

The device itself isn’t all that impressive looking. The researcher sticks the tag–about six inches long, with a mushroomed head and a short antenna–at the back of the dorsal fin with a small dart. Then a miniature computer inside the tag harvests three main pieces of information: light levels, water temperatures, and ocean depths. At a preprogrammed time, the tag sends out a burst of electricity, which quickly corrodes the aluminum pin that keeps it tethered to the dart. When it’s released, the tag floats to the water’s surface and begins winging packets of info to the nearest satellite, which then transmits them back to computers on earth to be interpreted and analyzed.

But to collect all that information, there can’t be any hiccups. Not only does a shark have to be close to shore; it has to be within three feet of the water’s surface for the researcher to even have a chance of tagging it– a precision-driven process that involves the deft touch of an experienced harpooner standing at the end of a narrow, shaky pulpit extending 20 feet out from the boat’s bow. Get all that right, and things can still get screwed up by a faulty tag, which is what happened to Skomal in 2004 when one device popped off the Naushon shark just a few days after he’d attached it. “I was heartbroken,” recalls Skomal. “I went from the highest highs in life to the lowest lows.”

Then there’s the weather. If it’s too windy or too cloudy, plane spotters can’t find sharks. Friday, for example–the day after Breen’s initial spotting–had been cut short after thick clouds rolled in over the Cape. Saturday, however, proved perfect. Deep-blue skies, limited wind, calm water; by 8 a.m. Skomal and his small crew–his assistant John Chisholm and Bill Chaprales and his son Nick–were circling the Chatham waters in Chaprales’s boat, guided by spotter pilots George Breen and Wayne Davis, a few hundred feet off Monomoy Beach.

The sharks were there, too, easy enough to locate, and three times Nick motored the boat up to a fish only to find that it was too deep to be tagged. Finally, at a little past 8:30, the crew rolled up on a small shark, maybe eight feet long, swimming in the shallows. With Skomal standing just behind him, Chaprales staked out his position at the end of the pulpit and waited. The 12-foot aluminum pole dangled from his right hand over the water, positioned not for throwing but for dropping onto the unsuspecting shark. After a few tense moments, he let it go, the small dart landing perfectly on the fish. “Yeah!” he yelled. Skomal and the others whooped it up, all of them taken aback by the sheer ease of it all. “We’d been out there an hour,” Skomal says. “I’d been waiting 30 years for this, but then …” He pauses and smiles: “… Greed kicks in. We’re here. Let’s not screw around. Let’s get more.”

Over the next week, in between bouts of stormy weather, the team tagged four more of the estimated 12 sharks that had come near Chatham. Reporters jumped on the news. All those tourists arrived. And the whole Chatham frenzy began its two-week run. “There were people coming down to the beach thinking literally that they could pet a shark,” says Chatham’s harbormaster, Stuart Smith. “They figured there were that many of them. ‘I’m here to see sharks. Where are they?'”

“How am I supposed to know?” Smith would tell them. He’d point to the water, where they could see Skomal and his crew in the distance searching for the fish. “There,” he’d say. “They’re somewhere out there.”

They are out there. But aside from people like Skomal and those who still manage to carve out a living catching fish, the chance to see a shark, to get close to the mystery, is rare. In part, that explains what happened in Chatham. It also explains the late-July circus that happens every year in downtown Oak Bluffs: the Boston Big Game Fishing Club’s “Monster Shark Tournament,” the longest-running such event in New England and perhaps the largest of its kind in the world. It’s a unique, if controversial, setting, where man and shark aren’t walled off by aquarium glass or a movie screen. Nowhere do the fascination with and fear of these fish converge as they do here.

Photo Credit : James, Steven

It’s July 2009, and this year, 130 captains have forked over the $1,500 entry fee and steamed their boats–everything from swanky 80-foot luxury crafts from Florida to smaller 30-footers from nearby Plymouth and Nantucket–here for a chance to win some cash and perhaps get a shot at a record or two. Right now, though, none of those boats is in sight. They’re all en route, returning after a full day of trolling and chumming in faraway fishing hotspots with names like “the Fingers,” “the Dump,” and “the Banana.”

And so we wait, a few thousand eager spectators, congregating at the southwest side of the harbor in anticipation of the first boat and a look at the tournament’s first shark. Teenage boys dangle their legs over the water on the sea wall, while their bikini-clad girlfriends stretch out next to them. Slightly inebriated, swaying to the music blaring from nearby speakers, an older crowd in dinghies mingles over in the harbor. The largest contingent stand and sweat under the beating sun around a metal fence marking off the weigh station.

That’s where I am when a bowling ball of man standing next to me pointedly asks, “You wanna see what a shark can do?”

And really, that’s the question we’re all asking: What can a shark do?What’s it capable of doing? By seeing a real one, maybe we’ll get a few answers. This guy, though, already has a good idea, and he’s more than eager to show me. With a deep, loud laugh he places his hand on my left shoulder and pulls up his right pant leg, revealing a long scar that wraps around his shin. It’s a lasting imprint from a nasty shark bite he received a couple of years ago while trying to haul in a fish on a small boat somewhere between Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. “One hundred and seventy stitches,” he says nonchalantly. “Lost a lot of blood.” He laughs. “No more shark fishing.”

But he’s not ready to give up at least seeing what others have battled for, and for that he can thank Steve James. James, whose background is in marketing and industrial design, is the man behind the tournament. He’s a one-man show, a powerful energy force who demands a lot from his volunteers and from the fishing captains who have an eye on the prizes, which total well into six figures in cash and equipment. There are strict weight limits, and boats are allowed to place only three species: mako, porbeagle, and thresher. It’s why at the end of the weekend the contestants will have killed only 13 sharks.

The tournament goes back to the mid-1980s, when the Boston Big Game Fishing Club, the outfit that oversees the event, was created by a small collection of Boston athletes and sports personalities–Bobby Orr, John Havlicek, and Curt Gowdy among them. But it was a sleepy little event, one that for the first decade of its existence couldn’t compare with the likes of the more-celebrated shark hunts in places like Montauk and Florida. By the mid-1990s Orr and the rest of the gang had relinquished their connection to Boston Big Game, and the tournament was running on fumes.

Steve James had taken second prize in 1996 when he’d hauled in a 454-pound blue shark. Sensing that the competition needed a more enterprising mind behind it, he approached the club’s owner about taking it over. In 1998, James organized and ran his first Monster Shark Tournament. The event grew quickly. A little press coverage didn’t hurt, either, and in 2001, when a 1,221-pound mako was caught off Chatham, the Boston Big Game brand made national headlines. ESPN signed on to broadcast the tournament, and by 2005, with the economy still roaring, James’s event was regularly attracting more than 200 boats a year and pumping up the local economy to boot, by funneling dollars into the Wesley Hotel, bars like The Lampost, and eateries like Nancy’s, where the jaws from that record-setting mako now hang.

But here on this shark-charged island, where Jaws-themed souvenirs always sell, James–who is unafraid to make statements like “Steve James defined big game fishing in New England”–is both revered and reviled. “I won’t even go downtown when it’s going on,” says one longtime shop owner. “It’s not a Vineyard event. I don’t like my home being known for this. I hope it stops altogether.”

She’s not alone. In 2007, voting on a nonbinding ballot question that asked whether the community should continue to allow public property to be used for events like the shark tournament, Oak Bluffs Town Meeting attendees almost ended it right there. A year later, the board of selectmen voted 3 to 2 to deny one-day liquor licenses to any shark tournament, putting an end to James’s pre-event banquet at a local park. Then in 2008 the Humane Society of the United States flew in Wendy Benchley, widow of Jaws author Peter Benchley, to speak out against the tournament and the detriment to the world’s shark populations that it posed. But James has been defiant. If anything, the controversy and the attacks have fueled him. In the press, he blasted Benchley as a contradiction.

“She’s inherited the fortune of the person most responsible for tainting the public perception of what sharks are about,” he said. “You couldn’t find anybody more ill-prepared to discuss this topic.” And in the wake of the liquor-license ban, he told reporters he had no plans to shut things down. “I will continue to hold this event until I’m 70 years old,” he said. “I might start holding three of these tournaments each summer. Who’s going to stop me?”

The weather, for one thing. On this weekend, James’s tournament has been cut short by a nasty storm that has pretty much wiped out the first day of fishing. Two nights ago winds and swells blasted boats, blowing out the windows on one 45-footer. The few that did try to fish the next morning fared even worse. One 29-footer went under about five miles south of the island–which only amplifies the crowd’s excitement and the stakes for today’s weigh-in, an all-or-nothing affair that can be won by a single catch. And James, who patrols the weigh-station area with a microphone, is both lobbyist and entertainer, pushing the importance of tournaments like his, where biologists stand ready to dissect the hauled catches for future research, all while the Jaws theme music blares from a pair of large speakers.

Around 3 p.m., the first boat steams in to the crowd’s cheers as it backs up to a pair of posts where its catch, a 299-pound thresher, is winched high in the air. The bloody stump of a fake hand hangs from the side of the boat. “I hope it’s got a fat belly,” yells one unimpressed spectator. As the fish is laid out and later chopped up into beefy steaks, James peppers the onlookers with more questions. “Who knows what kind of fish this is?” he asks. “Thresher!” they respond enthusiastically.

And on it goes. A 259-pound mako and a 320-pound thresher follow. The winner is a 361-pound porbeagle, a thick-bodied deepwater fish of the same family as the mako and great white. The contented (and richer by $25,000) captain of the boat, the Karen Jean II out of Marshfield, Massachusetts, sips from a can of Budweiser as James announces its weight and length (“Seven feet!”).

When it’s over and the evening takes shape, music blasts from several docked boats as crews drink and dance. On land, the spectacle of the day’s catch is on full display, as the head of one shark sits atop a cooler for passers-by to admire. Two high-school girls are particularly engrossed. “Oh, my gosh,” says one, a pretty blonde in pink pants and a multicolored top. “I gotta take a picture of this!” She leans in close with her camera phone, putting herself just a few inches from the severed head. She snaps and squeals in delight at her find. In a matter of seconds it’s winged out into the ether, to her sister, who’s horrified by sharks. “But she really wanted to be here!”

On an island that’s still a year-round home to a number of longtime fishing families whose roots here reach back generations, when it comes to sharks there’s one fisherman in particular whose name pops up again and again: Stanley Larsen. In the late 1950s his father and uncles were among the first longliners in Atlantic waters, ushering in a new era in a tuna and swordfishing industry still dominated by harpooners. Larsen grew up on the Vineyard and began fishing as a boy, going out with his dad’s crew on trips that took them 150 miles out, lasting several weeks at a time, “till the boat was filled up.”

Photo Credit : Aldrich, Ian

Today Larsens live all over the Vineyard–many, including Stanley, in Menemsha, an active fishing village on the island’s southwest side, marked by fabulous water views and steep home prices, even by Vineyard standards. It’s on Menemsha that Steven Spielberg and his crew descended for part of the filming of Jaws in 1974, building Quint’s shack down at the marina and recruiting local talent as extras and support personnel. Not far from the mayhem of Spielberg’s project–the unanticipated five months of filming, the technical difficulties, the constant budgeting issues that pushed islanders to refer to the movie as Flaws–Stanley Larsen owns and operates the Menemsha Fish Market on Dutcher Dock.

On a warm mid-November day I visit Larsen at his store. A steel-gray sky hangs overhead, high winds whip around the island, and save for one fisherman who’s shelling scallops, the marina is still. Larsen, a fast talker with a medium build and busy eyes, doesn’t fish anymore. Stiffer regulations and steeper expenses pushed him out of the business. But for a time in the 1980s he was one of the few guys to hunt sharks exclusively. He’d come to it by default: The large swordfish stocks his father and uncles had known had been almost wiped out. He’d made up for it with shark fins, a controversial delicacy in demand in Asia for shark-fin soup. The practice of finning–it essentially entails cutting off just a small section of the shark and dumping the rest of the fish–was made illegal in U.S. waters in 2000, but for a period Larsen was fetching $20 a pound.

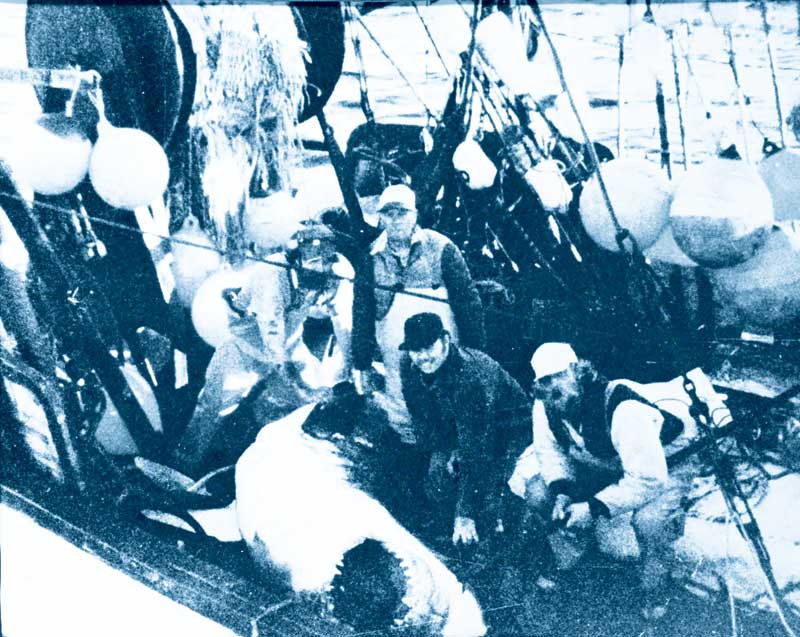

Photo Credit : Courtesy Stanley Larsen

It’s dangerous work. When a bull shark latched onto his cousin’s leg, Larsen had to pry open the fish’s mouth with crowbars. Another time, just seconds after his crew had hauled in a 150-pound mako, the fish started thrashing on the deck, pushing the crew toward the bow before flopping its way down the staircase toward the engine room. “I grabbed it by the tail and just started holding it,” Larsen recalls. “Another guy grabbed a rope and wrapped it around the tail, and we just pulled it back up. It was pure adrenaline that got that shark back on the boat.”

But the story he tells most often is the one he’s advertised the most. Larsen’s main business is fish, but he’s carved out some shelf space for items like T-shirts that say Amity (the island’s name in Jaws) and colorful wooden signs in the shape of a great white. But the stopper is a large faded print of Larsen and his crew with a great white, taken in 1983–and, of course, there are the jaws from that fish.

Larsen was combing the waters for swordfish on his big 52-foot shrimper southeast of Georges Bank. He’d harpooned his first fish when the white showed up, going underwater to take a bite of the catch before coming back up. So it went for three days; nearly the entire catch was ruined. Finally, Larsen went for the shark himself. He circled the area where he’d anchored. Around and around he went for two hours, hoping the white would pop up again. When it did, Larsen went after it.

“I harpooned him, but as soon as I did, he swung right around and swam toward the boat, coming toward it like he was going to attack it,” Larsen says. By his own estimate, the shark ran about 20 feet in length and weighed some 3,000 pounds. “Just before he got to the boat, he went straight down.” The shark was mortally wounded; the fight was over. Larsen’s crew eventually got the great white onto the boat’s deck, where they cut out the jaws and discarded the body.

Thanks to Larsen’s pilot, word of the encounter made it back to the island before the crew did. “The docks were lined with people,” Larsen says, “maybe a thousand of them. They thought we had the shark on the boat.” Larsen’s picture made it into the local paper, and the jaws became the stuff of legend around the marina. Even today, shark tournament entrants come into his shop and ask his advice. “I tell them to take a big old hunk of farmed salmon and put it at the end of the line,” he says.

It’s pushing late morning now, and Larsen has other business to attend to. A French couple struggles with their English to order a few lobsters from the tanks that line the front of his shop. Before I leave, I ask Larsen if I can take a picture of him with his shark jaws. We head outside, where he stands right in front of the shop’s door. “Make sure you get my sign in the photograph,” he says, raising the jaws triumphantly.

For now at least, the great white isn’t the perceived monster it once was. With depleted stocks, it’s now officially endangered, and the public’s reverence for the fish has spiked dramatically in recent decades. Just 50 years after Charles Tilton and his son received a hero’s welcome for their harpooning of that shark off Cuttyhunk, in September 2004 Greg Skomal found himself a target of Cape Cod residents who were concerned about the safety of a 14-foot female great white trapped in a saltwater pond on Naushon Island. “I was getting threats if I didn’t save the shark,” Skomal says.

But does that reverence have its limits? Where will public sentiment fall if what happened in Chatham in September 2009 occurs regularly? And what if the arrival of the whites comes in the middle of the season, not at the end of it? Will fear outweigh wonder?

All pertinent questions, because it’s possible that what happened in Chatham is a harbinger of things to come. Skomal believes that. In fact, he’s of a mind that along with the southern tip of Seal Island in South Africa and certain areas of the California coast, Massachusetts waters, with their ever-expanding population of seals, could become another shark hot spot.

That of course could be a boon to marine biologists like Skomal, who in mid-January received the first packets of info from a pair of great-white tags that popped up less than 50 miles off the Jacksonville, Florida, coast. But it could also be a threat to a jittery tourist industry, so dependent on human dominance of the waters. Recreation and nature may be headed for a collision.

“White sharks have been predominantly offshore, but with their incursion into shallow waters that may be changing,” cautions Skomal. “It could play out similarly to other hotspots. Predictable number of seals, predictable number of white sharks–potential human safety consideration. I can’t tell you how that’s going to play out. We know off the coast of California there are white-shark attacks on human beings. That happens. Not in big numbers. But all it takes is one.”

Then, just maybe, another kind of feeding frenzy might begin. Great white sharks can do that.

For more information on shark species, check out The Shark Handbook by Greg Skomal (Cider Mill Press, 2008) or visit: NewEnglandSharks.com

Ian Aldrich

Ian Aldrich is the Senior Features Editor at Yankee magazine, where he has worked for more for nearly two decades. As the magazine’s staff feature writer, he writes stories that delve deep into issues facing communities throughout New England. In 2019 he received gold in the reporting category at the annual City-Regional Magazine conference for his story on New England’s opioid crisis. Ian’s work has been recognized by both the Best American Sports and Best American Travel Writing anthologies. He lives with his family in Dublin, New Hampshire.

More by Ian Aldrich