Sanctuary for Desperate People in Boats | New England’s Gifts

Gruesome images today of refugees, fleeing poverty and war in North Africa and the Middle East, only to drown in Mediterranean waters, are arousing horror and sympathy around the world. European governments are faced with painful decisions: How many can they take in without being overwhelmed? The crisis is a reminder that New England has […]

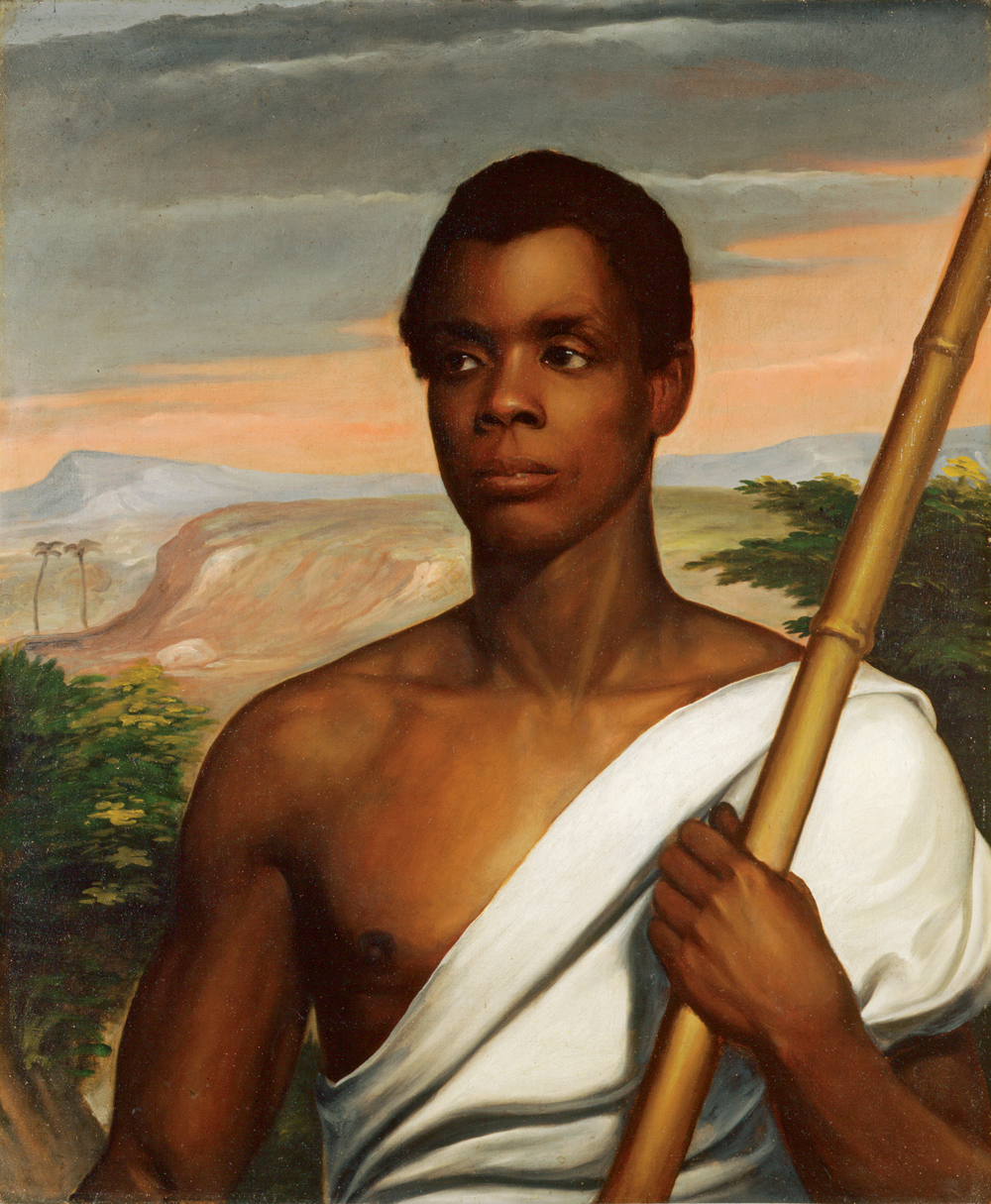

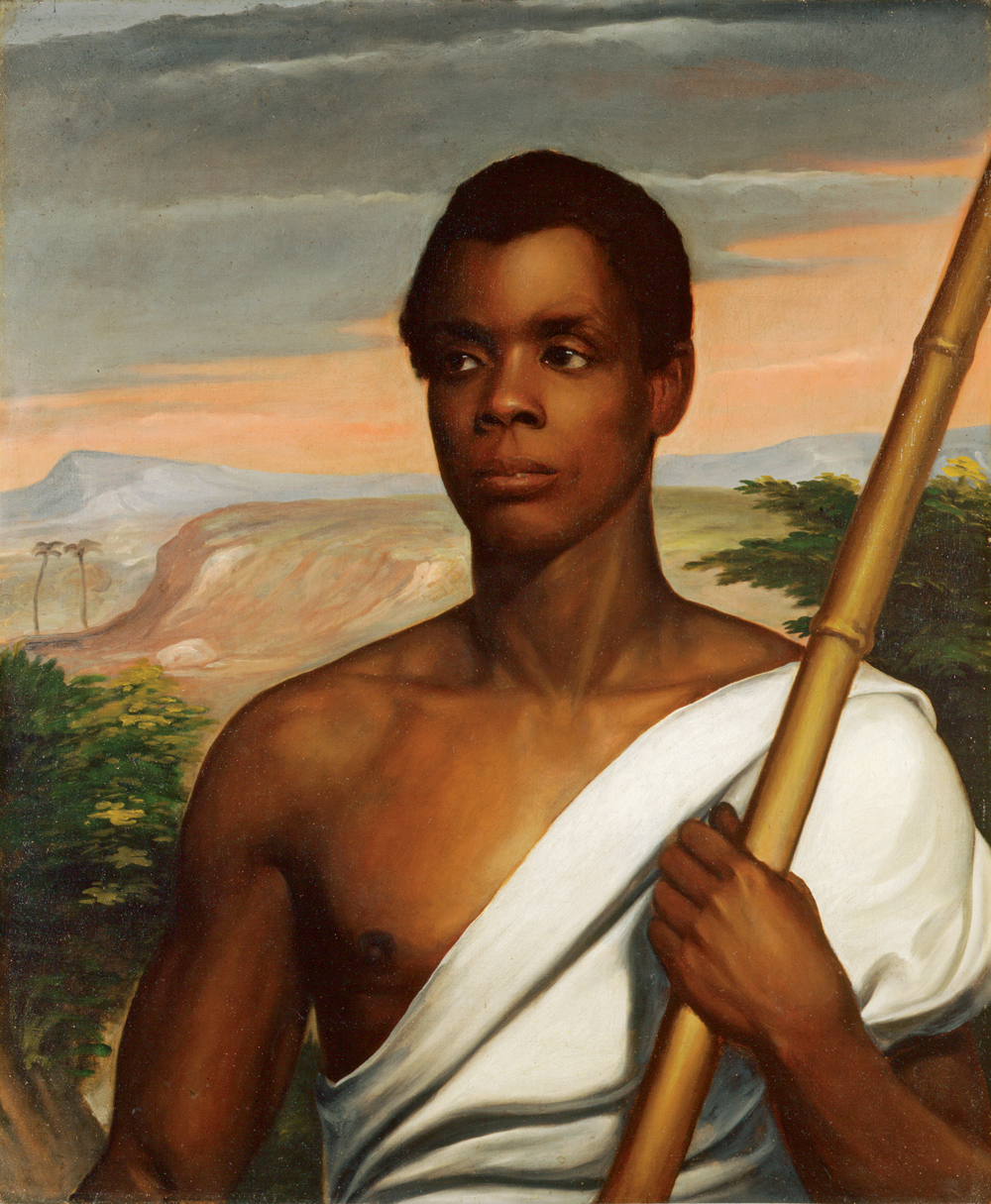

Sengbe Pieh (c. 1814–c. 1879), known in the U.S. as Joseph Cinqué, was a Mendi rice farmer who was kidnapped by slave traders in 1839 and led the captives’ uprising aboard La Amistad. Freed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1841, Cinqué and the other Amistad survivors eventually returned to Africa.

Photo Credit : Nathaniel Jocelyn, Cinqué, 1839. Oil on canvas, 30 ¼” x 25 ½”. New Haven Museum Collection

Photo Credit : Nathaniel Jocelyn, Cinqué, 1839. Oil on canvas, 30 ¼” x 25 ½”. New Haven Museum Collection

Gruesome images today of refugees, fleeing poverty and war in North Africa and the Middle East, only to drown in Mediterranean waters, are arousing horror and sympathy around the world. European governments are faced with painful decisions: How many can they take in without being overwhelmed? The crisis is a reminder that New England has offered sanctuary to desperate people in boats since the Pilgrims landed in 1620. Refugees fleeing political and religious oppression, or poverty and war, came in waves: an estimated 20,000 English between 1620 and 1640; Sephardic Jews from Portugal and Brazil in the 1700s; more than 1,500 Germans aboard the Lydia, bound for Waldoboro, Maine, in the mid-1700s; Irish and Italians in the 19th century; and Africans throughout, including a wave of Somalis since 2000.

Among the most desperate of all were 42 Africans from the Mendi country (now Sierra Leone) who arrived in a roundabout way in 1839. They were not refugees; they had been kidnapped. Chained aboard a Spanish schooner, La Amistad (“Friendship”), destined to be sold as slaves, they rose up, killed the captain and the cook, and ordered the surviving crew to sail them back to Africa. Soon after, the Amistad was captured by a U.S. warship off Long Island.

What to do with the Africans was a puzzle. They were taken to New London, Connecticut, where a judge put them on trial for murder. The charges were dropped, but the Spanish wanted the captives back. Two years later, in March 1841, the Supreme Court, after a dramatic defense by former President John Quincy Adams, ordered the captives freed.

While the lawyers argued, the Africans lived in Connecticut, at first in jail, then in the small town of Farmington, where a group calling itself the Amistad Committee took them. They planned to educate them and raise money for their passage home, where they hoped to convert more Africans to Christianity.

The arrival of 33 African men and three little girls (several captives had died in the meantime) was a shock even to a community that was a stop on the Underground Railroad. There was friction at first, but when the Amistads, as they came to be called, left eight months later, 100 townspeople gathered before dawn to see them off with tears and embraces.

They sailed for Africa on November 27, 1841. Once there, the Amistad Committee’s dream of a mission quickly evaporated. Some of the Amistads immediately stripped off their American clothes and disappeared into the bush, dancing and rejoicing. The only Amistad who ever returned to America was one of the girls, Sarah Margru Kinson, who attended Oberlin College, then returned to Africa as a missionary.

However, the failure of the mission was not the end of the Amistad story. Farmington’s willingness to shelter these strangers foreshadowed waves of Irish and Italian immigration that transformed the social, political, and economic landscape of the region.

Despite social and economic challenges, the waves continued to come ashore: Polish in the Pioneer Valley and Russians in Springfield, Mass.; Portuguese in New Bedford and Azoreans in Fall River; Armenians in Watertown, Chinese in Boston, and Cambodians in Lowell; Providence, Rhode Island, is home to generations of Cape Verdeans. More than at any time in history you hear Spanish on the streets of Nashua and Waterbury, the lilt of the Caribbean in Hartford, and Somali dialects in Portland and Lewiston. As people from lands far away and from far different cultures have sought to make new lives, they have made New England a richer, more diverse, more vibrant corner of America.—Tim Clark