Luke and the Lake

In remedying generations of environmental damage done to Lake Champlain, a master tinkerer finds his ultimate fix-it project.

Luke Persons has worked as everything from an auto mechanic to a dump truck driver, but cleaning up Lake Champlain may be his biggest job yet.

Photo Credit : Corey HendricksonWhen I was a young boy, my family would spend one or two days each summer at a camp on the shores of Vermont’s Lake Champlain. What I remember most is a jut of rock protruding into the water; I’d stand on its jagged edge and cast into the lake. it was deep and black, and I didn’t catch much of anything beyond the occasional perch. Still, I’d stand there for hours, casting and reeling, casting and reeling, captive to the rhythm of the pole, the whir of the outgoing line, the water lapping at the rock. Unaware that even then—this would have been nearly 35 years ago—Lake Champlain was headed for trouble.

Like many contemporary environmental woes, the troubles with Lake Champlain were long in the making but seemingly sudden in appearance. There are a lot of reasons for Champlain’s challenges, but most revolve around one central fact: The lake is besieged by phosphorus, which creates blooms of cyanobacteria (aka blue-green algae), which in turn contain substances known as cyanotoxins. These toxins have been known to kill fish and dogs and can be extremely harmful to humans if ingested. Additionally, the algae blooms block sunlight from reaching plants at the lake’s bottom, and when the cyanobacteria die off, the process consumes tremendous quantities of oxygen, resulting in the death of aquatic wildlife. The presence of blue-green algae has an economic impact, too: Popular beaches in and around Burlington are frequently closed, and real estate values have been hurt in the areas where outbreaks are most common—because as it turns out, a water view isn’t quite so appealing when the water is covered by a mat of toxic algae.

While the problem of blue-green algae has been understood and documented for decades, only in the past handful of years has it become widespread and acute enough to get public and political attention. This has led to an environment rife with finger-pointing, since the phosphorus at the center of the problem has many sources—fertilizer from lawns, golf courses, and other maintained green spaces; dysfunctional septic systems; wastewater treatment facilities; dairy farms—and not everyone agrees how to distribute the burden of cleaning up the lake and mitigating future runoff. The debate has become so fraught with tension that armed game wardens were dispatched to help maintain order at an October 2017 meeting about water quality issues at Lake Carmi, another Vermont lake that’s experienced high levels of blue-green algae. Because Carmi is close to Lake Champlain and is subject to phosphorus runoff from many of the same sources, it’s considered to be a canary in the coal mine.

To better understand the issues facing Lake Champlain and, I hoped, glean some historical context, I drove to Malletts Bay in Colchester last fall to meet James Ehlers, executive director of Lake Champlain International, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the health of the lake that provides drinking water to some 200,000 people.

It was late September, but the region was in the middle of a stretch of summerlike weather; the heat had provoked an outbreak of cyanobacteria, closing numerous beaches in the Burlington area. Ehlers, a fit-looking 49-year-old Navy veteran who answers his phone by barking his surname, had recently announced his candidacy for the 2018 Vermont governor’s race; he was running as a Democrat with a focus on water quality. We met at a small diner near the Malletts Bay boat access and ate omelets while Ehlers delivered an impressive oratory on the past, present, and potential future of the lake he loves.

The first thing to understand, according to Ehlers, is that Lake Champlain’s current condition is rooted in centuries of human activity. This began with the arrival of European settlers, who, taking note of the towering forests lining the lake, began sharpening their axes. These were impressive trees—white pine and oak, mostly—and the profusion of logs being floated across the lake turned Burlington into the third-largest lumber port in the country.

By the mid-1830s all the prime trees surrounding the lake had been harvested, which accomplished two things: First, it exposed thousands of acres of land, from which soil eroded into the lake and its tributaries, covering the rocky river bottoms that provided habitat for spawning salmon (it’s rumored that in the late 1700s and early 1800s, local officials would issue warnings about salmon runs, because the jumping fish would spook horses). Second, it allowed the expansion of Vermont’s wool industry, which had been growing steadily over the previous few decades. And while sheep offered a way out of the now-broken forest economy, their incessant grazing exacerbated erosion.

Eventually, competition from other states and countries heralded the demise of the wool industry, and Vermont farmers refocused their affection on the humble bovine, aided by the advent of refrigerated railcars that opened milk markets in Boston and beyond. And this, according to some, was the nail in Lake Champlain’s coffin.

The problem, said Ehlers, lies in the simple fact that the average dairy cow produces approximately 115 pounds of manure a day—which means that the 36,000 cows in Franklin County alone (Franklin serves as a watershed for the lake) are creating over 4 million pounds of phosphorus-rich waste daily. Couple this with the regular application of phosphorus-based fertilizers to feed the crops grown for these cows, and you begin to sense the magnitude of the issue.

“The truth is that nature can deal with the pollution; it’s building a system to deal with it as we speak,” Ehlers said, as he sipped coffee. “It’ll be a swamp, and it’ll trap everything. The mosquitoes will like it, the snowshoe hare will like it, the moose will like it.” He paused. “I just don’t think the humans will like it very much.”

I left my visit with Ehlers feeling a little overwhelmed. The challenges facing Lake Champlain seemed too big and intractable, too entrenched in well-established institutions. It didn’t help that I’d recently learned that the cost to clean up the lake—something mandated by the EPA under the Clean Water Act—was expected to exceed $2 billion over 20 years, and while some of the money would come from the feds, Vermonters would be on the hook for an estimated $25 million annually. Unsurprisingly, the debate over where this money would come from quickly became contentious. Should all Vermonters be compelled to pay, or only those directly responsible for the pollution? And what of the dairy farmers, already under severe economic stress due to low milk prices? These farms were responsible for an estimated 40 percent of the phosphorus entering the lake; did that mean farmers should shoulder 40 percent of the cleanup? Satisfactory answers to these kinds of questions seemed in short supply.

So I was more than a little intrigued when my friend Luke Persons turned to me one day and said, “I’m going to save Lake Champlain.” We were riding in his truck, an old Dodge diesel that rumbled impressively, so at first I thought I’d misunderstood. “You’re going to what?” I asked, lifting my voice above the clamor.

“I’m going to save Lake Champlain!” Luke repeated, louder this time. I turned to look at him. Then he added, “God willin’ the creek don’t rise.”

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

He was grinning, and I grinned back, and then the truck shifted down a gear to climb a hill, and the cab filled with noise.

The home of Luke and Terri Persons is a log house situated just off the crest of a small knoll at the edge of Deadman’s Swamp, in the northern Vermont town of Walden. It is not a particularly swampy swamp, and I find it quite beautiful and peaceful—especially as seen from the glassed-in porch off the rear of the house, which is where Luke likes to relax in his recliner, an insulated coffee mug filled with Jim Beam and Coke close at hand.

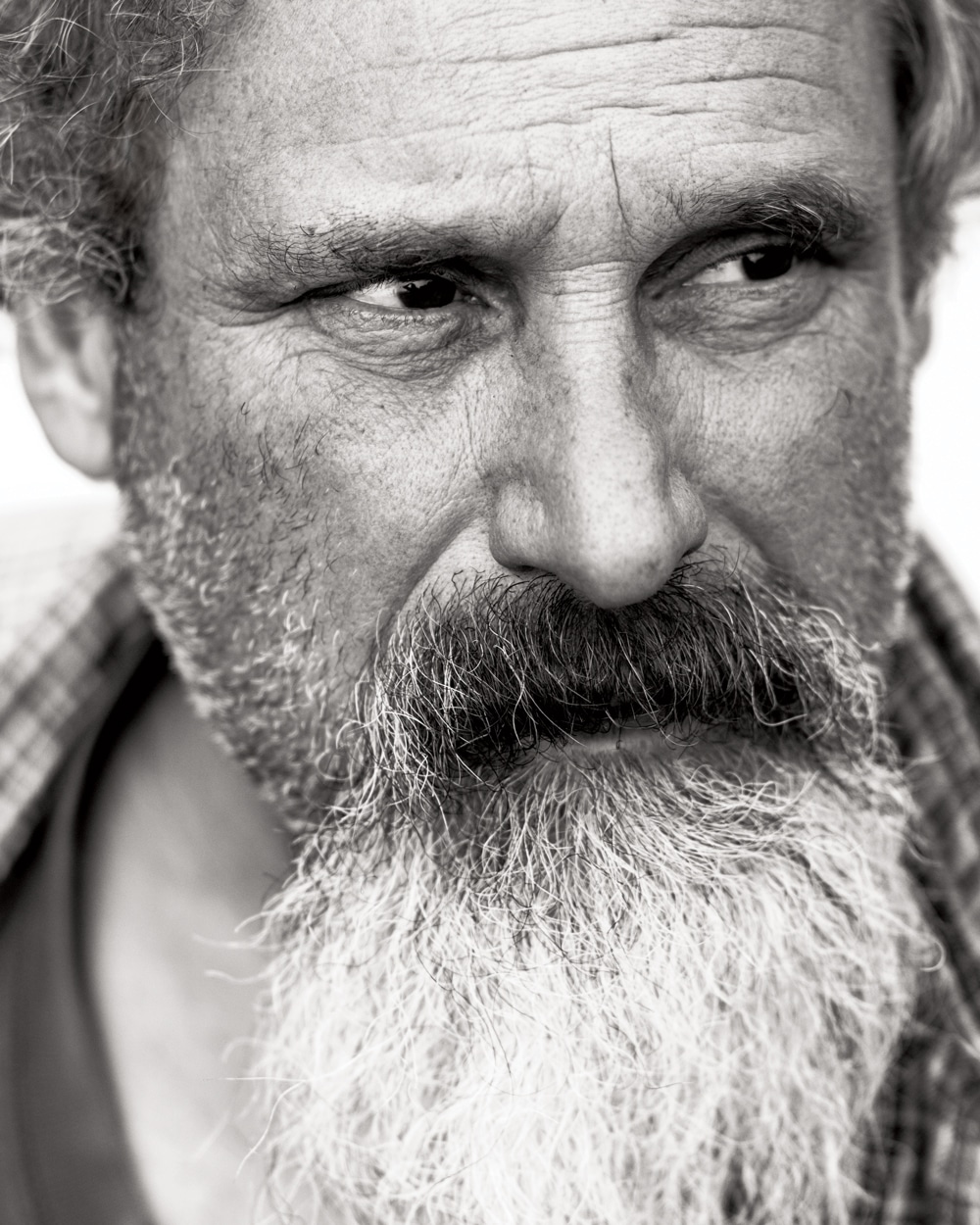

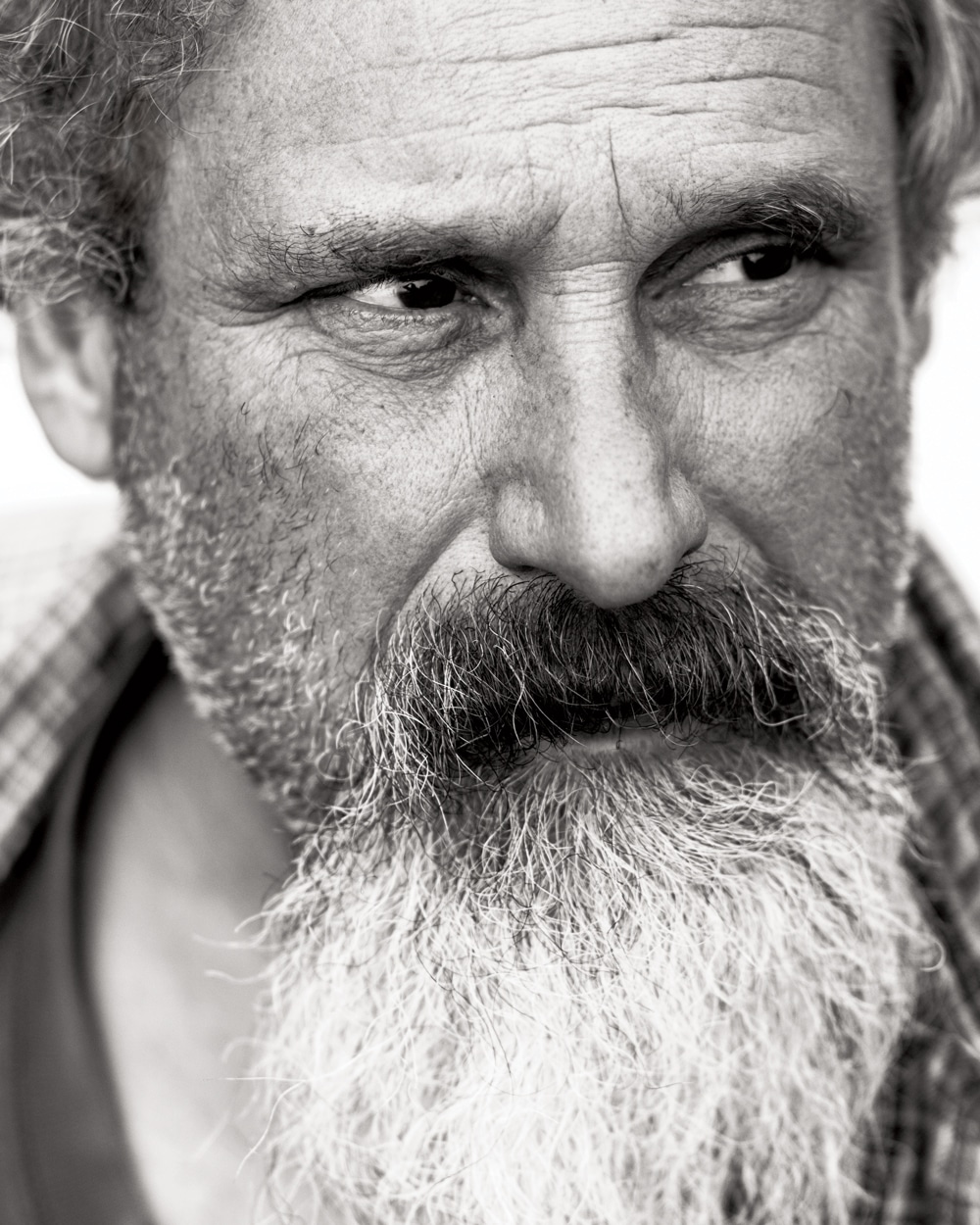

Luke is 58. He has a wily mop of gray hair that is slowly receding from his forehead. He also has a gray beard that descends from his face in a frayed “V” shape. He has thick eyebrows and a long nose, and he smiles a lot, by which I mean the man is always smiling. And when he smiles, his eyes squint, but not quite so much that you can’t see the twinkle. In this way—with the beard, the smile, the twinkle, and, let’s be frank, the ample stomach region—he cuts a vaguely Santa Claus–ian figure.

Luke Persons did not graduate from high school. He did not attend college. He was raised on a dairy farm a half dozen miles from here, and when young Luke complained to his mother about the oatmeal she’d serve for dinner when things were tight, she’d just look at him sternly and say that nothing would be tougher. He reads incessantly, favoring long works of historical nonfiction, and particularly those in which the focus is battle. He has been with Terri since he was 21 and she was 16 and pregnant with the first of their two daughters.

To make a living, he drives a dump truck, hauls equipment, does some welding and general repair, and makes maple syrup. Over the years, he has held a variety of regular jobs; one was at a tractor repair shop, another was as an auto mechanic. Once, he was hired to tear up 10 miles of train tracks in upstate New York. This is all a long way of saying that he’s not particular. He is also one of the smartest people I know.

There is evidence of Luke’s smartness in every nook and cranny of his home and shop, tokens of resourcefulness scattered about like shiny pebbles—the sawmill he built from scrap metal, for instance. Once, he led me into the basement and pointed to an automotive radiator in the corner. “What’s that look like?” he asked. “A radiator,” I replied. He nodded, beaming. “Yup. Out of a Hyundai. It heats the whole house.”

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

Then there’s the charcoal grill he built on a hinged arm and attached to the frame of the front door. The grill folds back against the house when not in use, and then when Luke and Terri have a hankering for cheeseburgers or T-bones in the winter months, it swings out for ready access from the cozy interior of the house. (Yes, the door has to be open, but let’s remember that car radiator in the basement, pumping out heat piped underground from the outdoor wood-burning furnace, also homemade.) And when a switch in the control panel of my excavator went bad, Luke swapped it with one from a scrapped DVD player. The equipment dealer had told me I’d need to replace the entire control panel for a cool $800; Luke charged me 20 bucks and said, “That should work fine, God willin’ the creek don’t rise,” smiling all the while. (He says, “God willin’ the creek don’t rise,” with great frequency.)

Although his father was handy enough, Luke credits his mother’s brother, Chet, for the genes and the inspiration behind much of his own ingenuity. “He was always making stuff like I do. I remember he took some British sports car and put it on an American frame,” Luke said. “He was one of those guys you’d look forward to coming around the farm. Everything stopped. Or in my world it did, anyway.”

It’s worth noting that all the projects Luke seems proudest of involve the comingling of major vehicle components, such as the Dodge ambulance he got for free and converted into a dump truck, or the industrial-size wood splitter he built from the axle of a Toyota truck, the frame rail of a Peterbilt tractor trailer, and the engine of a Ford lawn tractor. There’s even a hydraulically activated arm to load the unsplit rounds of wood.

When I think of Luke’s particular brand of intelligence, I think of the kinds of smarts that were once common in this country but which seem to have entered a steady and inexorable decline, as our lives have become increasingly dependent on technologies and economic forces beyond our control. It’s an intelligence rooted in the urgency of need, a relationship to a specific place, and the capacity to make do with the materials and resources at hand. It’s not the sort of intelligence that makes anyone rich (though it occurs to me that if the world were more fair, it would be), or wins any awards, or garners much, if any, recognition beyond the small community it serves. It is, in a word, unassuming.

Or at least that’s what I thought until Luke told me he had a plan to save Lake Champlain. Though not a “Great Lake” per se, to the millions of people who live within an easy drive of this 490-square-mile body of water, and to the hundreds of species of birds and waterfowl who populate its depths and shores, Champlain is no small potatoes. And whatever Luke’s plan might be, I figured it had to be vastly more complicated than anything he’d tackled before.

As it turns out, I wasn’t wrong.

According to Luke Persons, the answer to Lake Champlain’s woes can be found in something you probably haven’t even heard of: biochar, a type of charcoal made from biomass. It’s produced by subjecting the biomass feedstock—in Luke’s case, wood chips—to high temperatures (generally 800 to 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit) in the absence of oxygen. The result is an extremely porous high-carbon material that retains large quantities of water and nutrients such as, yes, phosphorous.

Luke stumbled upon biochar a few years ago. “I was looking to make charcoal, and I discovered this whole thing,” he told me. At the time, Luke and his friend Roger Pion were considering what business venture they might embark upon; they’d been thinking wood pellets but soon determined there was too much competition. “We mulled the idea over, then got to talking about biochar,” Luke explained. “Right from the beginning, I told Rog, ‘This is how we’re gonna save Champlain.’”

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

Luke had seen the lake’s troubles firsthand. “I like fishing up there,” he said, “and I’ve been there when the algae’s so bad it just stinks.” Still, I suspected that his intentions were not strictly altruistic but rather rooted in his compulsion to fix things. It wasn’t so much that he wanted to save Lake Champlain. It was that, having seen a way in which it might be done, he simply couldn’t not try.

The origins of biochar can be traced to South America, where it’s believed to have played a role in traditional agricultural practices for more than 2,500 years, prized for the same nutrient-capturing qualities that have piqued Luke’s interest. Indeed, charcoal-rich soil known as terra preta covers an estimated 10 percent of the Amazon Basin. Deposits have also been found in Ecuador and Peru, as well as in the West African nations of Benin and Liberia.

As Luke sees it, there are many ways in which biochar could be implemented in defense of Lake Champlain. It could be distributed over the land, where it would bind runoff before excess nutrients enter the lake. It could be built into industrial-size filters to be installed at the outflows of agricultural waste systems. Or it could be distributed in shallow trenches to intercept the nutrients as they worked their way toward the shore. “You can’t just shut off the phosphorus,” Luke explained to me. “But you can capture it.”

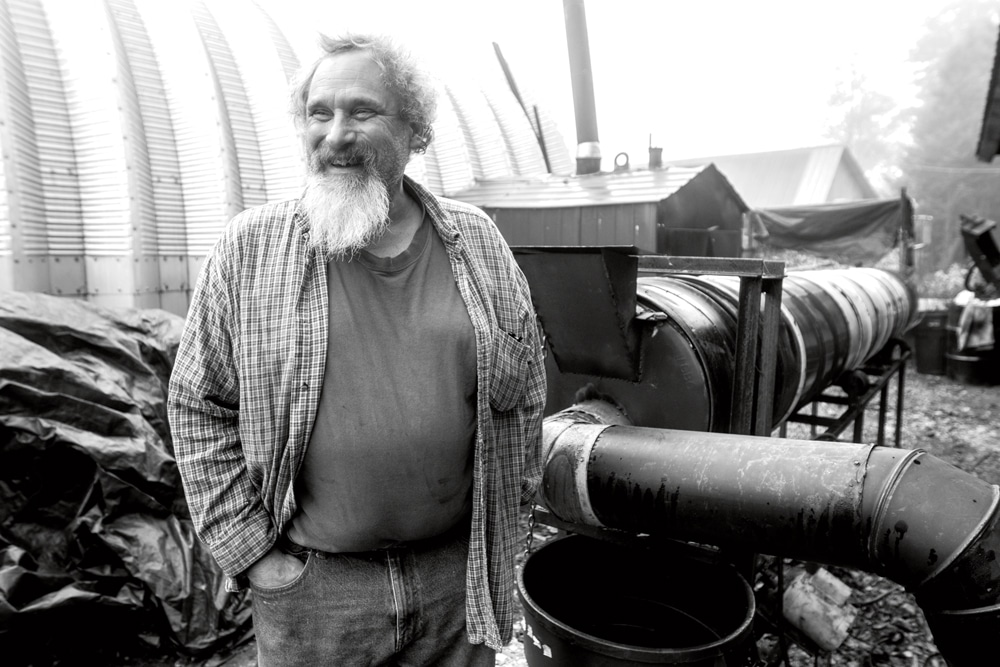

Producing biochar requires a highly specialized contraption known as a retort, which is, in effect, an over-engineered wood stove. I first saw Luke’s retort in action on a mid-August morning as Luke and Roger gathered to make char and continue working out kinks in the system. I found them under the low roof of a three-sided, wood pallet–walled shed at the edge of Luke’s barnyard, which was populated by an impressive array of cast-off machinery and parts: An old tractor tire, still mounted to its rim, weeds flourishing in the hollow center. A long-abandoned rototiller. A snowmobile improbably perched atop a stack of wood pallets. A motorcycle with its front wheel removed. A pitchfork. There were chickens strutting about, and a duck drinking from a bucket of water. Luke was padding around in a pair of hiking moccasins, monitoring the retort and making adjustments as necessary.

Naturally, Luke built the retort almost entirely of material diverted from the waste stream. For instance, the chain that drives the wood chip conveyor was gleaned from an old hay elevator, and the blower runs off a fan sourced from an air-cooled Volkswagen engine. To aid in the pre-combustion drying of the wood chips, he welded together five 50-gallon drums that now ride in a homemade stand and rotate via a small electric motor (also salvaged). And the auger that feeds the furnace began its life as a trailer jack. “It’s all homemade,” he told me, and chuckled, not because it was funny (it was merely true) but simply from the sheer pleasure of having created something useful out of so many abandoned bits and pieces. Luke chortled again. “I can’t believe it works!” he exclaimed. I nodded my agreement, but I was pretty sure he’d known it would work all along.

I walked to the far end of the retort, where finished biochar dropped off a chute into a trash can. The char was warm but not hot, and I reached into the can and extracted a handful. It was light and crumbly-feeling. To be honest, it felt like not much of anything at all.

Can Luke Persons really save Lake Champlain? I’d posed the question to James Ehlers, and his answer was not encouraging. “Look, I’m all for biochar. I’ve got no problem with it. It’s good stuff,” he said. “Hell, it wouldn’t matter to me if someone discovered that lollipops would save the lake.” We were standing on the dock in Malletts Bay when he said this, and I imagined a rainbow of brightly colored candies bobbing in the water. “But the truth is, biochar is only addressing the symptom. The real problem is that there’s too many freakin’ cows.” (Except he didn’t say “freakin’.”)

For further clarification, I turned to Michael Wironen. A graduate fellow at the University of Vermont’s Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources, Wironen is studying the ecological economics of Champlain’s phosphorus problem. The challenge, he explained, is that even if every source of phosphorus imported into Champlain were halted today, the lake could still suffer for decades, thanks to the abundance of “legacy phosphorus” that’s accumulated in the soil. “There’s been a phosphorus surplus every year since 1925,” he said. “Remediation solutions like biochar are very important, but we still need to reduce phosphorus dramatically. Even if we bring things into balance, we might not see evidence in water quality for years to come.” In short, he was saying the same thing Ehlers told me: There’s too many freakin’ cows.

So, yes, there are too many cows, and maybe even a few too many people. And yes, it’s probably true that Luke Persons’s goal of saving Lake Champlain will remain beyond his reach. The hard truth is that biochar is no more likely to save Lake Champlain than windmills are to reverse the effects of climate change; the systems and structures creating the damage are too well established and powerful to be overcome by any one act of mitigation. There can be no singular remediation, no lone silver bullet. It will require a sustained effort on the part of all involved, and every bit of remediation counts. Every bit means the lake will be healthier than it would otherwise have been.

Photo Credit : Corey Hendrickson

It’s not as if Luke and Roger are going to quit trying, anyway. Six months after I first saw the retort in action, I found them in Luke’s kitchen, alternately troubleshooting an industrial-scale wastewater biochar filter under construction, exclaiming over an old drill bit sharpener Luke discovered amid a pile of scrap, and browsing a recent edition of the Gun Trader’s Guide.

Since my visit in August, they’d attempted to attract $500,000 in seed money but failed, despite having won a regional entrepreneur pitching competition. Their intent was to build out the filter business (Green Mountain Biochar was the name), which they could then leverage into developing larger-scale systems intended for lake cleanup. Notwithstanding the lack of funds, they seemed undeterred, and they’d even hatched a new back-of-napkin plan to drag algae from the lake’s surface, combine it with biochar, and burn the mixture in electricity-producing digesters. The biochar would act as a catalyst to improve the efficiency of the digesting process.

Roger left to pick up a piece of PVC pipe for the filter they were fussing over, and Luke and I walked down to his shop so he could install a couple of belts in the engine compartment of the former ambulance. Soon, the belts were installed, and Luke led me up a short hill to show me the old ambulance body so that I might better understand the scope of the conversion. Along the way, we passed an old refrigerator, a discarded oil tank, a dune buggy half buried in the snow, and a shed with a “piglets 4 sale” sign affixed to its side.

“See that?” asked Luke, after I marveled over the ambulance body. I followed his gaze to what looked to me like random lengths of steel best suited for the scrapyard, though by now I knew enough to understand that to Luke, this wasn’t scrap. Not even close. “That’s the frame from an ’86 Toyota truck.” He was grinning to beat the band. “Yup, that’s a project. God willin’ the creek don’t rise.”

Ben Hewitt

The Hewitt family runs Lazy Mill Living Arts, a school for practical skills of land and hand. Ben's most recent book is The Nourishing Homestead, published by Chelsea Green.

More by Ben Hewitt