Ghost Moose of the Northern Forest | Our Land, Our Sea, Our Future

Where have northern New England’s moose gone? In the late 1990s, they numbered around 7,500 in New Hampshire; now that state’s population is estimated at 3,500. In Vermont, a high of 5,000 just over a decade ago has fallen by nearly two-thirds to the current estimate, 1,750.

by Cheryl Lyn Dybas

In northern New Hampshire’s Coos County in early April, sunset comes early. At just after 6 p.m. on a back lane with no signpost to mark it, the light turns gold … orange … indigo. All is still except for a chilly wind that rattles the bare branches of red maples and white birches. Parked on the shoulder, I watch the woods quietly through my car window.

Photo Credit : Roger Irwin

I’m just north of the town of Milan, population 1,337. I’ve come to this remote land along the Androscoggin River on a four-day search for moose, the largest member of the deer family and one of the most majestic symbols of northern New England. Longtime moose biologists warned me of a slim chance of success, though. “In that length of time? Good luck,” said Kristine Rines of the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department. “You could be here for weeks and not see a moose.”

Where have northern New England’s moose gone? In the late 1990s, they numbered around 7,500 in New Hampshire; now that state’s population is estimated at 3,500. In Vermont, a high of 5,000 just over a decade ago has fallen by nearly two-thirds to the current estimate, 1,750. And while biologists are working on the updated numbers for Maine—which in 2012 was home to an estimated population of 76,000—“there are definitely fewer moose,” according to Lee Kantar, moose biologist for the state’s Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife.

Early on, this downward trend was largely fueled by state-permitted hunting, a move meant to keep the moose population in balance with its habitat. But more recently, these massive animals—which can weigh as much as 1,500 pounds—have been decimated by a creature that’s no larger than half an inch: the winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus). Warmer winters have been a boon for the ticks, which attach themselves by the thousands to moose, draining their hosts of blood and strength, making them vulnerable to illness, even causing death. The surge in winter ticks has also given rise to what Rines and her colleagues call “ghost moose,” animals who’ve lost much of their coats through repeated attempts to scratch the ticks off. “Some have so little hair they’re almost all white,” Rines reports.

Ghost moose, in fact, are what I’ve come out to Coos County to find. I drive slowly down the road, knowing that moose depend not on old-growth forests, as is often thought, but on young ones—what scientists call “early successional” forests—and the sapling-filled woodlands along my route seem like ideal habitat. And then, suddenly, I see them: Along a roadside slope that hides a pond at its base, huge dark creatures have appeared at the forest edge.

A cow moose, trailed by a calf, slowly comes into view through the crimson-tinged branches of red osier dogwoods that edge the woods. Less than 50 feet in front of me, the cow crosses from one patch of shrubs to another. Then, with a gait that is somehow both ungainly and surefooted, she meanders midway up a hill before stopping and looking back, her distinctive deer-with-a-hump shape silhouetted by the setting sun, the calf following close behind. Their flanks are nearly bare, the fur stripped off.

Imagine what it’s like, being covered with tens of thousands of ticks, so many there isn’t one patch of unbitten skin. Even worse, springtime is when the moose are at a physiological low point, according to Rines: “They’ve used up their reserves over the winter, then they have all these insects biting them, making them itch, draining their blood supply, and generally making them miserable.”

Two miles down the road I spy two more cows, both looking pregnant, ambling out of the forest. Like the earlier cow and calf, the moose make their way uphill and into the dense undergrowth. They, too, have lost much of their fur.

Within minutes, all four ghost moose have vanished into the night.

———

It was spring 1992, near the town of Lewis in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, when Cedric Alexander saw his first ghost moose. “I was in the woods doing a spruce grouse breeding survey,” says Alexander, a wildlife biologist for the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, “when I spotted a moose in the distance that somehow looked different.” Closer inspection revealed the moose had lost a lot of hair, making it appear oddly pale. Alexander reasoned that a heavy tick load was to blame but didn’t see it as immediately alarming. At the time, “bad tick years were infrequent, and the moose population was still increasing,” he explains.

Photo Credit : Roger Irwin

Kristine Rines saw her first ghost moose that same year, during a moose conference in Ontario. It wasn’t until about five years later, though, that she spotted her first tick-infested moose in New Hampshire. “Then we started noticing slight declines in our moose population, and I assumed it was probably related to ticks,” she recalls. “After repeated attempts to get approval for a study, we were finally successful in 2001.”

The findings of that initial, five-year study were stark and conclusive: Winter ticks were the primary cause of moose mortality in northern New Hampshire, where moose density (and therefore tick density) is highest. Now Rines and her colleagues are working on an even bigger study, a four-year project overseen by veteran moose ecologist Pete Pekins, who chairs the natural resources department at the University of New Hampshire. With Maine and Vermont also participating in the research, it’s reportedly the largest study of New England moose ever conducted.

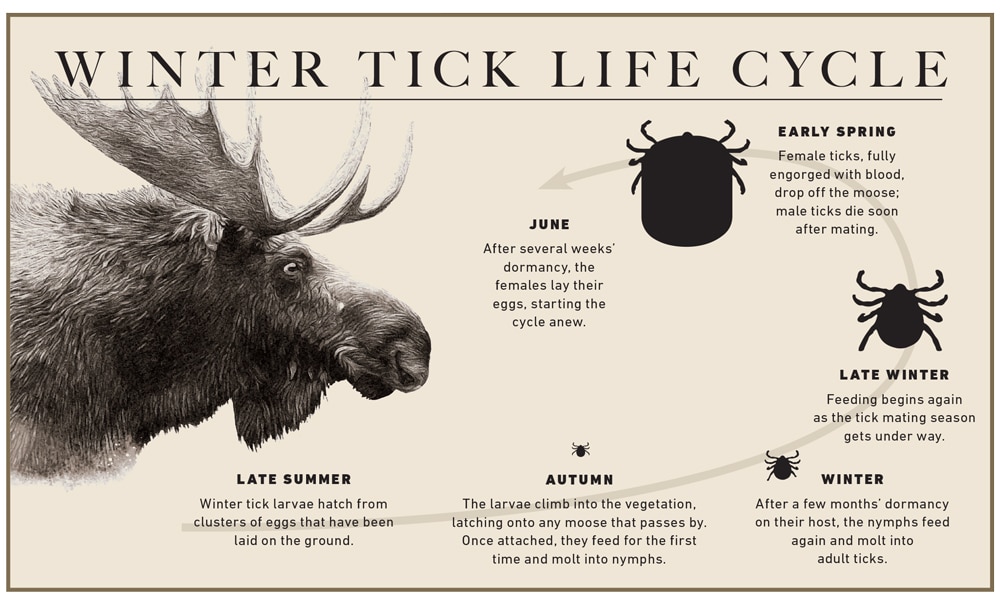

Yet even as biologists work to get a clearer picture of what’s happening in the moose population, weather trends keep turning up the heat. Of the 18 warmest years on record, 17 have occurred since 2000—with 2016 being the hottest since record-keeping on global temperatures began, in 1880. And milder winters are key in winter tick booms. After a last meal in early spring, the females drop to the ground, where they’ll lay their eggs; they’ll likely die if they encounter ice or snow, but “if they land on uncovered, snow-free leaf litter,” says Kantar, “it’s a field day.”

Photo Credit : Roger Irwin

Also good for winter ticks: a warm autumn. That’s when the next generation has hatched and is most vulnerable to cold and snow. The milder the weather, the more larvae will survive to climb into the vegetation—usually to the average chest height of moose—and wait to latch onto a passing host, a behavior that biologists call “questing.” The larvae quest in groups, interlocking their legs; since a female winter tick can lay 3,000 eggs, this means hundreds of larvae may land on a moose at one time. Once settled, they’ll feed, rest until late winter or early spring, and feed again. The only time a moose can escape the onslaught is summer, after the adult ticks drop off and before the larvae start latching on.

It’s little wonder, then, that many see the warming planet as the moose’s ultimate threat. “If climate change keeps ramping up,” says Ed Reed, a wildlife biologist for New York state, “we could lose moose completely in the Northeast.”

———

The vision of the four ghost moose is still with me the morning after my vigil, as I head to Milan Luncheonette & Variety in Milan, New Hampshire. I’m meeting Rines and Pekins for breakfast, along with three of Pekins’s assistants, graduate student Dan Ellingwood and field technicians Todd Soucy and Jake DeBow.

Waiting for hot egg sandwiches, we talk of moose and how to find them. Rines, a plainspoken woman with shoulder-length silver hair, has been the New Hampshire moose biologist for all but two of her 35 years with the Fish and Game Department. Although someday Rines will retire and “go watch birds for a while,” right now she’s fully committed to moose.

“This time of year can be very sad for moose,” Rines warns, as we discuss plans for today’s expedition. “Biologists call it the ‘season of death’ because so many calves die now, mostly as a result of winter ticks.”

Tens of thousands of winter ticks—ranging from an average load of 35,000 to as many as 150,000—may feed on one moose simultaneously. Adult moose typically can survive the tick assault; calves, however, with their smaller bodies and lower blood volumes, often cannot. A tick-infested calf may lose its entire blood supply over a few short weeks.

In parts of New Hampshire where biologists have tracked moose via GPS or radio collars as part of their current multistate study, the calf mortality numbers have been sobering. In 2014, more than 60 percent of the collared calves died; by 2016, it was up to 80 percent. “We’re losing an entire age class of moose,” Pekins laments. (Toward the end of the year, though, Pekins will send me a bit of good news: The mortality rate among New Hampshire’s moose calves last spring was only 30 percent, thanks in part to the tick-killing early autumn snowfall of 2016.)

After breakfast, our group makes its way north on Route 16, heading to New Hampshire’s North Region Moose Management Unit. The North Region and the adjacent Connecticut Lakes Region represent the state’s best moose habitat: a northern forest in early succession.

Our first stop is at Pontook Dam along the Androscoggin River. We scan the timberline: no moose. Not far down the road is a spot where two weeks ago researchers found a sick calf. “[It] took three or four steps, then died within a few minutes,” recalls DeBow. Since the area has plenty for moose to eat and the calf’s stomach was full, he says, the likely cause of death was blood loss from winter ticks.

Back in our vehicles, we veer left on Fire Tower Road, which leads to Milan Hill State Park, 10 miles north of Berlin. There, we climb slippery steel stairs that zigzag to a lookout cabin at the top of the park’s 45-foot-high fire tower. “Getting up there tests your lung capacity, that’s for sure,” Rines jokes. The height gives us views of both the White Mountains and the Green Mountains, and beyond to the Adirondacks of New York.

Pekins sweeps his arm over the seemingly endless forest below. “Clear-cuts have been rotated here, resulting in lots of regrowth,” he says. “It’s great habitat for moose. There may be fewer of them, but they’re out there somewhere.”

———

All of which leads to the question: Can we do anything to change the future for the northern New England moose?

“People have suggested everything imaginable for dealing with the hordes of winter ticks,” says Rines. “Ideas include putting out insecticide-laced salt licks, using robots that apply insecticide to the ground, spraying the woods with insecticide, placing tick collars on moose, and releasing guinea fowl to eat ticks.”

Unfortunately, none of these ideas are feasible. There’s no spray-based pesticide that targets only winter ticks, for example, and with repellents “you’d need a pressure washer to get the job done,” Rines says, since you’d have to get through the moose’s thick, shaggy hair to apply it to the skin.

As most biologists see it, there are just two strategies, both difficult. “We put the brakes on climate change,” Pekins says, “or we decrease the numbers of moose by letting winter ticks run their course or by increasing hunting to bring down moose densities.”

Studies have indeed shown that with fewer animals to feed on within a given area, “tick numbers begin to fall,” says Stephen DeStefano, moose biologist at the Massachusetts Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. In Massachusetts, where moose number about 1,000, the population has been relatively stable over the past few years, he says. “There’s certainly no indication of a precipitous decline. Winter ticks are present, but they don’t seem to be having a big effect.”

Similarly, the 500 to 1,000 moose in New York’s Adirondack Mountains are “virtually tick-free,” says New York’s Ed Reed, who works for the Department of Environmental Conservation. “You can count the number of winter ticks on an Adirondack moose on less than one hand, probably because there aren’t enough moose to get the tick cycle going.”

The trouble is, nobody really knows how far the moose populations in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine must drop before they reach the “sweet spot,” and the comeback can begin.

On my final day in moose country, it’s again a beautiful April twilight, the sun vanishing behind the trees, as I’m drawn back to the road where I saw the ghost moose. I am hoping for a glimpse of one last moose. But the hillside is empty.

I linger until the light is gone. The moose may have been just beyond my line of sight … maybe, I hope, wading in the pond east of these woods. In a few months it will be summer. Next season’s winter ticks are only eggs on the forest floor, still weeks away from hatching and beginning their quest to survive, their journey to find a host.