The House That Changed Everything | Kragsyde

There was only one way a young couple with little money could build a replica of a storied 19th-century Massachusetts mansion: They had to believe they could.

A bathroom featuring a Victorian cage shower and a mural by Goodrich.

Photo Credit : Bret MorganBy Jane Goodrich

The tale of Kragsyde—and what happened when a young couple first traveled to see the legendary shingled mansion in Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts—unfolds like an O. Henry short story. Except, that is, the events stretch out for 15 years, as Jane Goodrich and James Beyor re-create the turn-of-the-century beauty from scratch. In the afterword of Goodrich’s forthcoming novel about original Kragsyde owner George Nixon Black, The House at Lobster Cove, she tells her real-life story of encountering Kragsyde and then building the extraordinary replica now perched on Swan’s Island, Maine. —Ed.

Photo Credit : Bret Morgan

Coup de foudre, the French say, literally “bolt of lightning” but meaning love at first sight. How better to describe the instant when a chance meeting alters a life? For who can ever expect the sudden place, or glimpse, or turn of the page that will change everything?

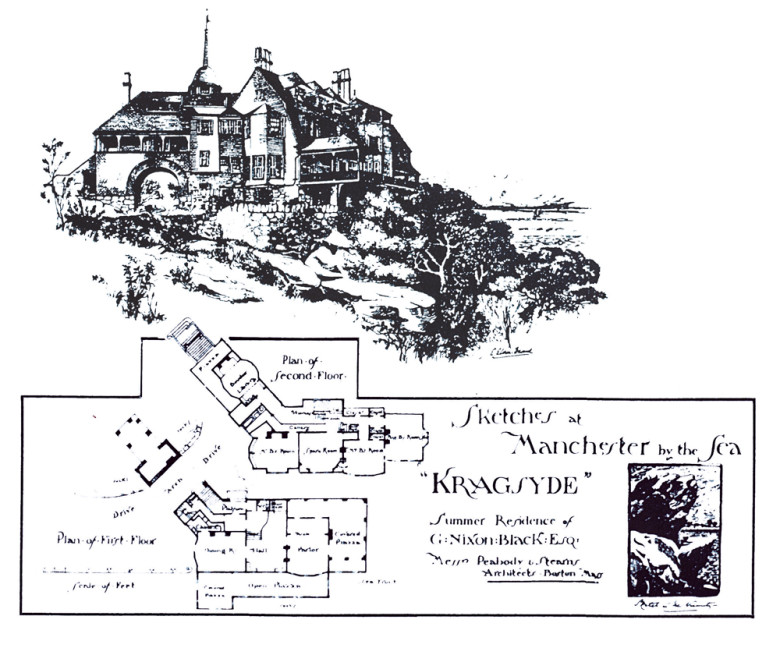

I first met Kragsyde in an old box of books my father brought home. I was barely a teen, and paid little attention to the text or the title of the book, but the photographs and drawings gave me goose bumps. These were the most beautiful houses I had ever seen. Not impossible fantasy castles, nor the monotonous ranch-style structures of my own time. Shingled and playful and shaggy, like a favorite dog, full of mysterious rooms placed at odd angles. Fanciful windows I longed to peer from, deep cool porches, turrets with pennants flying from spires, promising endless summers. And the names: Grasshead, Sunset Hall, Wave Crest, Seabright.

I studied them all, but even then my eyes could discern the masterpiece: Kragsyde. With its fantastic arch large enough to drive through, its beautiful stones, its romantic perch above the sea, this was the pinnacle. Completely beguiled, I clipped the photograph from the book and pasted it into a scrapbook. The sepia photo, held in my hands for the first time, was both a daydream and a seed.

Photo Credit : courtesy of Historic New England

Seven years later, in 1979, I was working in a sunny window in my college library. I was a sophomore, engaged to be married to a man who was already on his path to becoming a master builder. We often talked about the house he hoped to design and build for us. I was studying graphic arts and photography, but on that day I was awaiting the delivery of several books for an art history project. When the stack slid off the library cart, the top volume, The Shingle Style and the Stick Style, by Vincent Scully, had a familiar photo on its cover. Once again, the attraction was instant. Lightning had struck in the same place twice.

My fiancé, James Beyor, and I decided to make a trip to Manchester-by-the-Sea, in Massachusetts, to find Kragsyde. We became more excited about our own house plans as we drove, devising ways in which elements of the style could be incorporated into our own house. But our search was brief: Ten minutes after we entered the Manchester Historical Society, we learned from the docent, Frances Burnett, that Kragsyde had been torn down in 1929. Sensing our disappointment, she offered to take us to the original site. Rounding the edge of Lobster Cove and seeing the bare cliff top where I had always envisioned the great house standing was like witnessing an extinction.

“The building plans can still be found in the Boston Public Library,” Ms. Burnett told us, consolingly.

In a small diner in Manchester, James and I ate lunch and commiserated. It was an easy first step to our mutual complaints that the world of 19th-century beauty was slipping away, to be replaced by the cheap and poorly crafted. It was frighteningly easier to come to our next wild thought. Why not rebuild Kragsyde? We knew how. It was a leap, a whim, an oath, an ambition, a naïveté, and a motif for the long marriage that followed.

Photo Credit : courtesy of Jane Goodrich

Photo Credit : courtesy of Jane Goodrich

Photo Credit : courtesy of Jane Goodrich

The next day in the Boston Public Library, we encountered our first reality. We never thought about our jeans and longish hair, or our obvious poverty, when we entered the rare-book area where the plans for Kragsyde were housed. It never occurred to us that simple interest would not be enough of a key to open the archives. But since we had no academic credentials, the vault remained closed. “You might want to call the man who donated the plans,” the librarian suggested.

Wheaton Holden, professor of architectural history at Northeastern University, was an expert on Kragsyde’s architects, Peabody & Stearns. As an educator, he was also no doubt accustomed to youthful exuberance and possessed the wisdom to foster it.

“We’re going to rebuild Kragsyde!” I told him over the phone when I reached him that day.

“I think that’s just great,” he replied.

In a matter of weeks he gave us copies of the plans and all the relevant photographs and drawings he’d amassed in his years of research. If Kragsyde was a seed planted in my childhood, it was Wheaton Holden who watered it.

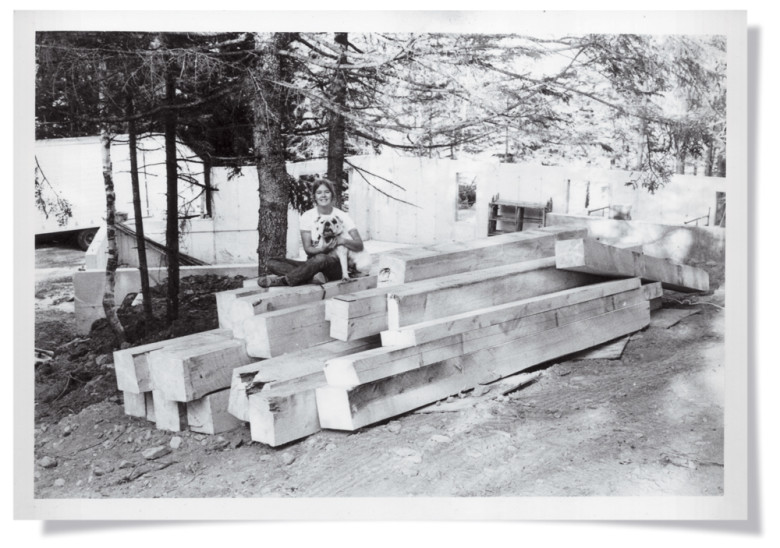

Photo Credit : Bret Morgan

By 1982, when I graduated, we’d saved as much money as we could, built a little model of the house, and bought an affordable seaside property in a too-small town in Maine. The daydream was about to be replaced by work—15 years of it, performed entirely by us, mostly on nights and weekends after coming home from our day jobs. We embraced it with diligence and no small dose of delight, using old techniques and traditional materials. As finances waxed and waned, the progress was sometimes slow, but each month brought advances and hard-won satisfaction in seeing the sepia photograph become tangible, as beautiful in our own century as it was in the century it was designed. We could look out the fanciful windows and walk under the fabulous, legendary arch, and we had built them ourselves.

Photo Credit : Bret Morgan

Photo Credit : Bret Morgan

—

Together with a college classmate named James van Pernis, Goodrich launched Saturn Press in 1986, producing greeting cards and stationery printed on antique presses. Her “day job” was paralleling the evening work of resurrecting traditional construction methods. At the same time, Goodrich found herself becoming increasingly fascinated with George Nixon Black, the original owner of Kragsyde.

To my 19-year-old self, George Nixon Black was no more than the original owner of Kragsyde, but as we rebuilt his house, I felt his ghost in every corner. It took 10 years of research on this elusive man to realize his life was as romantic and compelling as the house he occupied, and that his was a story worthy of being told.… The curious thing was how in searching for Black, I also found myself.

And in that seeking, she recalls, a bit of ephemera floated up from the past:

It came from the Manchester Historical Society, and from the pen of Frances Burnett, the docent who was the first person we met on our long journey. Buried in their archives was a copy of a letter she’d written in reply to someone who had sent her a newspaper article about our rebuilding of Kragsyde:

“I well remember this young couple who visited the Society back in 1979. I took them to the site of the old house and told them it had been torn down. They had an old rattletrap car and I remember wondering how they could ever contemplate building such a mansion, but they have done it, and more power to them.”

Photo Credit : Bret Morgan

Photo Credit : Bret Morgan

In fact, we never went back to the Boston Public Library to see the plans; with the help of Wheaton Holden, there was no need. Yet even though I never laid eyes on those original elevations, I know every line of the house. How could I not, after building it, after laying the rafters of those familiar roof lines, and mixing the mortar for the enormous chimneys?

I know how the shingles travel the eaves, and where the snow builds up in those valleys. I know both its past and its present. The huge shadowed porch where Black played billiards, where I today hang a hammock, and the bow window where I find a sunny place for a blue and white bowl of flowers.

Adapted from the afterword ofThe House at Lobster Cove, a novel about George Nixon Black by Jane Goodrich, to be published this spring by Applewood Books. To learn more, go to houseatlobstercove.com.