The House at Allen Cove | E.B. White House Tour

E.B. White wrote some of the most enduring words in American literature from his farm in Brooklin, Maine. Now, the house, barn, and 44 acres could be yours.

The interior of the barn, looking out to the fields. Hanging in the doorway is the rope swing made famous in E.B. White’s 1952 children’s classic, Charlotte’s Web.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

The swing still hangs by the barn doorway. There may or may not be a spider spinning her web in the darker corners of the rafters on this early July afternoon in North Brooklin, Maine. Allen Cove, a small inlet in Blue Hill Bay, sparkles in the sunlight. There are gardens of flowers so beautiful that the eye goes to them even before settling on the sturdy white clapboard farmhouse that has stood here for more than 200 years.

I knock on the farmhouse door. No answer except for the bark of a dog. A man who I soon learn has been the caretaker here for over 15 years is working in a shed by the barn and calls out, “Just walk on in, they know you’re coming.”

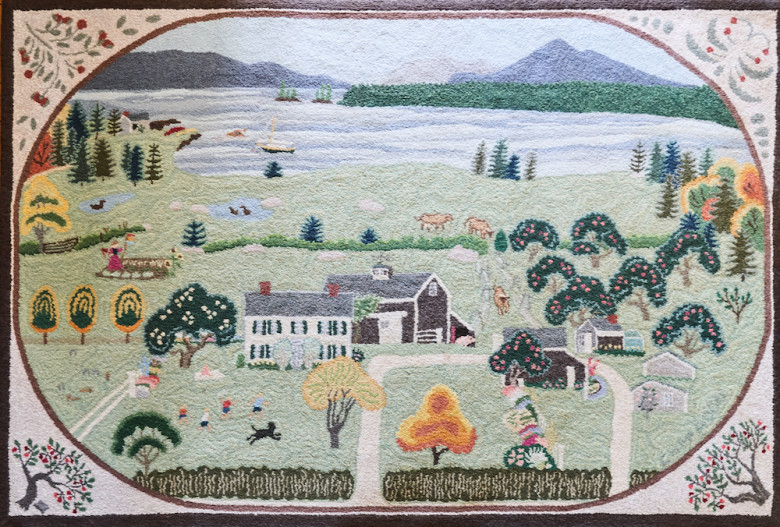

Robert Gallant is waiting inside, and I follow him to a breezy sunlit room that looks out on a patio, gardens, a pond, and a sweeping view of the bay and the distant mountains of Acadia National Park. He and his wife, Mary, have been married nearly 60 years, and for more than half of those years they have traveled from their South Carolina home to spend summer and fall on their 44-acre saltwater farm, one of the loveliest and best preserved in Maine.

They arrived here only a few days earlier, and Robert greets me in a voice with the slow, easy inflection of the deep South. He’s led a vigorous life, with a highly successful business career as a managing partner of the Gallant-Belk department store chain and a property developer. But he’s on the back end of his eighties now, and lately he’s had a rough go of it. His right wrist is heavily wrapped after a recent fall, and he’s reluctantly coming to terms with what he can and can’t do anymore. I learn all of this over the next few hours as I hear Robert’s and Mary’s stories, which speak to a deep love for everything my eyes can see—as well as those things that undoubtedly only theirs can. There is a bittersweet feel to our time together. It’s clear they do not want to leave. They know they should. It is time, they say, to downsize to one home and live closer to their four children and seven grandchildren, who remain in the Carolinas.

Mary enters the room. Within moments she connects the threads of their story with those of the previous owners, E.B. and Katharine White, who bought the farm in 1933 and moved here full-time four years later. Katharine died in 1977, her husband in 1985. “I’m sure you want to do the Charlotte’s Web thing,” Mary says, and quickly ushers me to the barn and sheds that once housed the Whites’ hay, sheep, geese, chickens, pigs and (of course) spiders, and probably a rat or two. The barn itself also provided the setting for one of the most beloved children’s books of all time.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

We walk from room to room in what is possibly the most impressive and well-kept barn I have ever seen. There is that rope swing, immortalized in Charlotte’s Web as the one from which Fern and her brother launched themselves from the loft. Here’s where Wilbur’s trough would have been, Mary says, and “right here”—she points—“is the hole where I tell children Templeton the rat would scurry back and forth.” Light pours into the barn from massive windows the Gallants found in a salvage yard. “We think we have changed the barn for the best,” she says. Many of the improvements, she notes, had to do with “opening rooms up to more light.”

Every spring, Mary would arrive to open the house and ready the gardens for planting. For many years, in mid-June, a teacher from a school 90 miles away would bring her class to visit. “They sit on hay bales in the barn,” Mary says, “and we play the recording of Mr. White reading Charlotte’s Web. They swing on the same rope swing that they knew Fern had; they sit on the milking stool where Fern had sat. I wanted them to grow up remembering this day. I hoped one day they’d want to find Mr. White’s other writings.”

The tour of the barn and its sheds reveals a river of belongings flowing from one family to another—a collection of worn work gloves, an icebox from the Whites’ New York apartment, and also pieces the Gallants picked up as they canvassed flea markets and antiques shops. “I’ve been here all these years and I keep finding things,” Mary says, showing me a newly discovered stack of empty grain sacks.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

We go back into the house, where the tour continues. There is much to take in: 12 rooms, six working fireplaces, three and a half bathrooms, 19th-century stenciling on the stairway walls, a wood cookstove in the kitchen. Here is the sunny study used by Katharine White, a revered New Yorker editor and avid gardener, now an office for Mary. Next we look in on the darker, north-facing office that belonged to E.B. White, now Robert’s. Upstairs, Mary opens the door to a bedroom that was once heated in winter by a small woodstove set into a fireplace. “This was Mr. White’s room,” she says. “He was afraid of fire,” and she points to the rope ladder squeezed into a corner of the closet.

After the tour, we rejoin Robert in a room that was formerly the old woodshed. They floored it and shined it up, and it’s become their summer sitting room, where the breeze flows through open doors and a day can slide by as you simply look out to the sea and mountains. They take turns telling me how they found this farm—a story Robert clearly relishes.

In 1939, his family came to the Maine woods. “Can you imagine how happy a 10-year-old boy could be sleeping in a log cabin?” he says. “I woke up to the smell of my mother frying bacon. The memory stayed with me.” He had always loved sailing, and “Maine has the finest sailing in the world. I wanted to have a sailboat in Maine.” In the early 1980s, he flew to Bangor, rented a car, and gave himself 10 days to find a place to put that sailboat. “The woman at the rental counter told me, ‘Don’t go lower than Bucksport,’” he says. “‘Lower than that is too close to Boston.’” Off he drove, and eventually he found his way to the Blue Hill Peninsula. “I said to Mary, ‘We have to go up there.’”

And two years later, that’s what they did. It was Mary’s first time in New England, and they found what she calls “the perfect spot,” a cottage on 12 acres overlooking Eggemoggin Reach, famous among sailors. It was perfect, and they bought it—except now Robert had also seen the prettiest saltwater farm on the entire peninsula, the one owned by E.B. White. Months after White’s death, Robert learned that his son Joel was interested in selling it privately. They met on the farm. “I walked all over,” Robert says, “thinking like a developer, and I came up with a figure I was willing to pay. Joel quoted a price and it was almost the same, to the nickel. We shook hands. I took out a checkbook to leave a deposit. He said, ‘We don’t need that. We shook hands.’”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

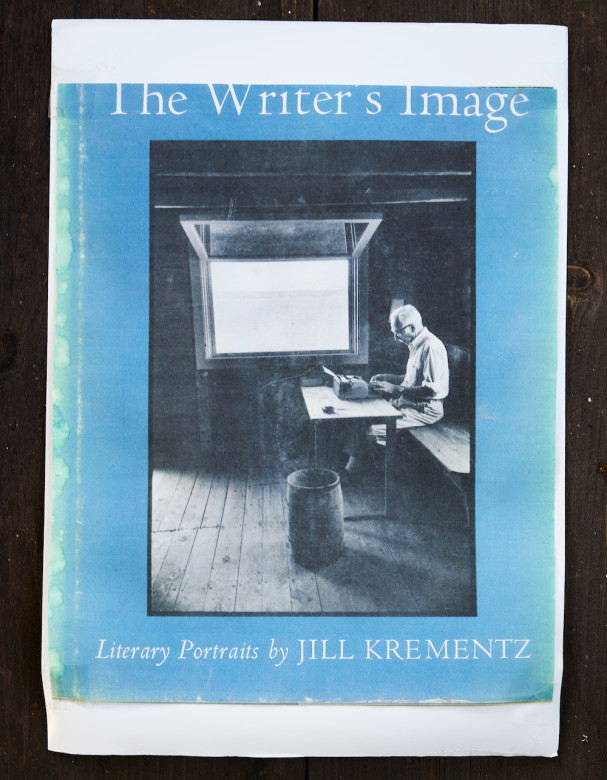

“And now,” Mary says, smiling, “we suddenly had two houses on the Maine coast.” For the next few years, before they sold it, they rented out the cottage or loaned it to friends; in the meantime, they made the farm their own. Robert laid out an allée of trees that led like a magical pathway to the trim boathouse where, when the weather was right or there was too much going on in the house, E.B. White would retreat with his black Underwood typewriter. There he built a simple table and bench, placed a barrel for waste and an ashtray by his side, and with the sea breezes for company typed some of the most elegant and memorable sentences in the English language. For their part, the Gallants brought in some extra furniture and added fresh paint, helping to make the boathouse, like the entire farm, what E.B. White had wanted: a place for families to love.

The Gallants’ children grew up and brought their own children here, where they found a sturdy dock for launching boats and brave bodies into the chill water, and trees bursting with ripe peaches, pears, and apples. There were berry bushes, endless pasture to run through, clams to dig and fish to catch, evening campfire cookouts, and lazy days for reading.

And as the Gallants were putting down roots, they had a guide: Henry Allen, who had worked for the Whites for 37 years. “I said, ‘Henry, we will need someone to look after this place,’” Robert says. “Henry said, ‘I’ll stay on for 30 days. See if you like me, and I’ll see if I like you.’” Allen stayed on for seven more years before finally retiring in his late sixties. “Oh, it broke my heart when Henry left,” Mary says. “He was the spirit of this place. He was our connection to the personal side. Henry said people tried to encourage Mr. White to name the house, which he thought pretentious, but he said if he had to, he would call it ‘Two Big Chimneys and a Little One.’”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Whoever comes after the Gallants will soon learn that E.B. White simply wanted to be left alone, to write and to farm and to be a member of the community. He did not want his home to become a shrine, a museum, a writers’ retreat; he wanted it to stay just a family home. His granddaughter Martha White, a staunch defender of her grandfather’s wishes, told me she believes the Gallants have made it their own, which is how it was meant to be. She hopes it will forever be that way.

“I feel I’ll always want to come back to Maine,” Mary says. “But I will miss just settling in, the way you do when it’s home.” Robert’s voice grows a bit huskier as he chimes in, “This house, this barn, this property is very dear to our hearts. These have been the best summers of our lives.” Mary says she will miss the sunrise over the cove, and the full moon rising “right there”—she gestures toward Harriman Point—adding, “You can read a book by its light.”

E.B. White never knew the Gallants, but he’d know what they’re feeling. He told one of the few interviewers whom he welcomed to the house, “This place doesn’t fit me since Katharine died. The only thing is, I really had to live here. Also, I love the place, and it’s my home.”

The property is priced at $3.7 million. Serious inquiries only, please. For more information, contact Martha Dischinger at Downeast Properties in Blue Hill, Maine, at 207-266-5058 or by email at msd@brooksvillemaine.com.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen