The ‘New’ New England Cooking

Boston chefs find inspiration in farm-fresh ingredients as they serve up traditional New England recipes with a twist.

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza

For too long, New England cuisine has suffered an identity crisis—or, more specifically, a split identity. On the one side, the pride of the region: fried clams, lobster rolls, and a perfect bowl of chowder, made all the more delicious by the patina of history. On the other side, a culinary punch line of underseasoned fish and overcooked potatoes. The resourcefulness and frugality of early New Englanders inspired cod cakes and Indian pudding—but compared with the culinary glories of, say, France, which at that time was enjoying the splendors of the Ancien Régime, our food was decidedly plain and practical, the product of a harsher climate than Europe’s or even the American South’s.

“While the New England culinary profile was framed by climate and geography—short growing season, poor soil, proximity of the ocean—the moral culture was dictated by the Puritans and their Boston Brahmin descendants,” says Professor Merry White, a food anthropologist at Boston University. Plain food wasn’t just practical; it was a safeguard against the perils of sensuality. As the country grew and the population began to diversify, early attempts to broaden the local diet were met with resistance.

“Italians who immigrated to Boston were ‘processed’ in settlement houses where the cooking classes trained oil and garlic out of their repertory,” White says. “Boiling was the only moral cooking method. One young social worker at the turn of the 20th century wrote in her casebook about a particularly recalcitrant family: ‘Still eating spaghetti; not yet assimilated,’ she wrote, despairingly.”

And so New England cooking mostly retained its rather plain reputation through the end of the “Continental” cuisine era of the 1970s. Meanwhile, the tides were shifting in the South and in California, where chefs began to explore the notion that, just as in Europe, America could produce legitimately praiseworthy regional food at the fine-dining level. In New England, we saw Chinese, Portuguese, and Italian cuisines work their way into the mainstream, but it took another decade before a few young chefs—most notably Jasper White—escaped from the rut of heavy sauces and overly fancified French cuisine. In the early 1980s White began reexamining our regional heritage at restaurants such as Jasper’s and Seasons. He hedged his bets that New England cooking could stand on its own; he made the seasonal ingredients of the Northeast his muse, turning out elegant recipes with a respectful hand. His first cookbook, Jasper White’s Cooking from New England, published in 1989, has become a classic.

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza

With White leading the movement, other chefs followed. The availability and quality of local ingredients began to change as producers partnered with chefs. Mussel, clam, and oyster “farms” soon dotted the coastline. Farmers’ markets sprang up, with their fresh herbs and heirloom tomatoes, and long-shuttered gristmills began grinding whitecap flint corn again.

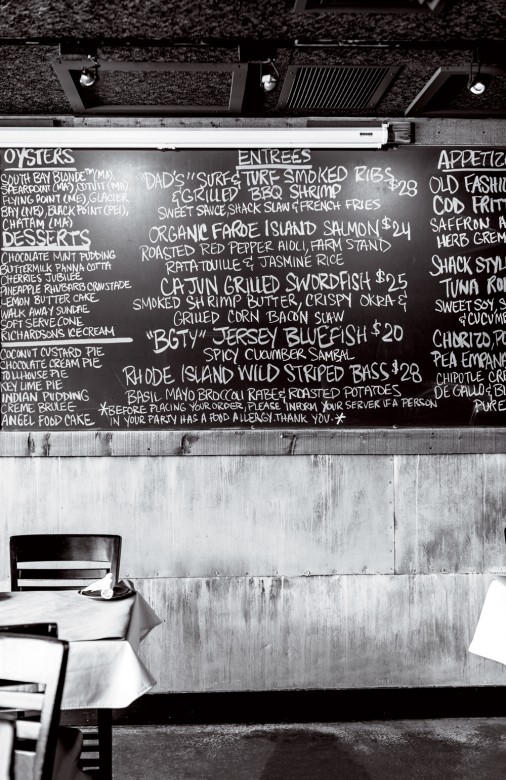

Thirty years later, Jasper White is still going strong, shifting from fine dining to his large, family-friendly Summer Shack restaurants (in Boston, Cambridge, Dedham, and Connecticut’s Mohegan Sun casino), yet he’s still cooking contemporary renditions of the classics. And now a new crew of Boston-area chefs is approaching our heritage as a source of inspiration rather than something to resist. Not content to merely source their ingredients from local farms, they’re returning to traditional dishes and reworking them in their own ways.

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza

It’s a turning point for New England food, and it’s certainly not limited to the Boston area. But there’s a particular sense of momentum there. In addition to Jasper White, we spoke to four other chefs who have embraced what we’ll call the “new New England cuisine”: Marc Sheehan of Loyal Nine; Jeremy Sewall of Island Creek Oyster Bar and Row 34 (which has a second location in Portsmouth, New Hampshire); Mary Dumont of the newly opened Cultivar; and Will Gilson of Puritan & Company. And we also came away with five easy-to-make recipes that proudly serve up tradition with a twist.

[haven_recipe post_id=”87633″]MARC SHEEHAN | LOYAL NINE

In a November 2015 review of Loyal Nine in Boston magazine, food writer Corby Kummer pondered the phenomenon of “Boston’s braver chefs” who are in the “process of reinventing New England’s culinary vernacular.” Kummer was somewhat skeptical, while supporting the idea in theory. “Whether [Sheehan] can summon food that’s tasty, rather than just an academic exercise,” he wrote, “is the real question.” And it’s true that Sheehan and his earnest team are digging deep into the history of early America, serving thoughtfully prepared and thoroughly researched food that takes inspiration specifically from Colonial coastal Massachusetts. It’s as didactic as it sounds, but the fried soldier beans, served as a bar snack, are hard—no, impossible—to stop eating, as are the whole roasts, whether rack of pork or bluefish, served family-style, in the colonial style.

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza

“As a kid,” Sheehan confesses, “I was a picky eater.” But he couldn’t resist the sweet smell of molasses, salt, pork, and onion that wafted through his childhood home. The intoxicating aroma came from his dad’s baked beans, made from scratch—old-school: “My dad would soak the beans on Friday, bake them on Saturday, and on Sunday they’d get served with dinner. No one could wait for Sunday for a taste—the aroma was everywhere in the house—so on Saturday, he’d pull the onions out of the pot and we’d eat them on toasted rye bread.” Slow-cooked onions stolen from classic New England baked beans, slow-cooked in a traditional beanpot: A recipe like that doesn’t need any updating.

[haven_recipe post_id=”87635″]MARY DUMONT | CULTIVAR

And now we tackle pot roast, that mainstay of the Yankee Sunday dinner. It has certainly never lost popularity—it’s comfort itself. But the stuff of fine dining? Chef Mary Dumont takes her cue from the original, but bathes a chuck roast in equal parts broth and apple cider for a hint of sweetness and acidity to balance out the richness of the meat. And rather than leave the vegetables in the liquid to cook for hours, she adds them toward the end of the braise, preserving their texture and individual flavors.

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza

The entire menu of her new restaurant in Boston’s Ames Hotel expresses a love of New England, particularly in the fall. “I grew up in Hampton Falls, New Hampshire,” Dumont says. “It was all apple orchards and farms—literally and figuratively ‘apple county.’ It was Ladies’ Auxiliaries, hayrides, hot apple cider, cold apple cider, hard apple cider, apple-cider doughnuts—apple-cider everything.”

[haven_recipe post_id=”87638″]JEREMY SEWALL | ROW 34 + ISLAND CREEK OYSTER BAR

Childhood memories also inspire Jeremy Sewall’s food. In fact, the history of this region is in his DNA. His ancestors go back centuries—chances are there’s a Sewall Road or a Sewall Bridge or a Sewall Hill near you, if you live in Massachusetts or Maine.

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza

Sewall spent his childhood summers in southern Maine, where his uncle worked as a lobsterman. “What New England produces is amazing,” he says. “The farming, the fishing, the cheesemaking, and the artisanal products that are being made here … Just the last 10years have shown such a dramatic increase in the quality of what’s available.

“The cooking part is simple,” he laughs. And with more access to quality ingredients, there’s more room for creativity—all of which is evident in his book The New England Kitchen (Rizzoli, 2014).

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza

Take baked clams, long a regional staple, particularly the giant stuffed quahogs that Rhode Island is known for. We’ve all had renditions in which the clams are tough from overcooking and overpowered by bread. They might still taste good at a clam shack by the sea, but in Sewall’s hands, the clams aren’t hidden; they’re given texture with minced apple, which, as with Dumont’s pot roast, brightens their flavor. Same historic ingredients, different era.

[haven_recipe post_id=”87640″]WILL GILSON

Just down the street from Loyal Nine, the dining room at Puritan & Company has a modern/vintage-vibe that telegraphs a certain comfort with the past: a mason-jar chandelier; barn- board wall panels; an early-20th- century Glenwood stove, which serves as the host stand. Chef Will Gilson says that it hasn’t always been easy to sing the praises of regional cooking among his peers. “I feel as though I’ve spent so much time defending New England food,” he says. “It was exhausting. Now I just cook what makes sense to me.” Gilson’s menu can span several continents for inspiration but always circles back to his home turf.

Photo Credit : Michael Piazza