History of Boston Cream Pie | A Pie in Cake’s Clothing

Why should the origin of something as good as Boston cream pie be such a mystery? Learn more about the history of Boston cream pie.

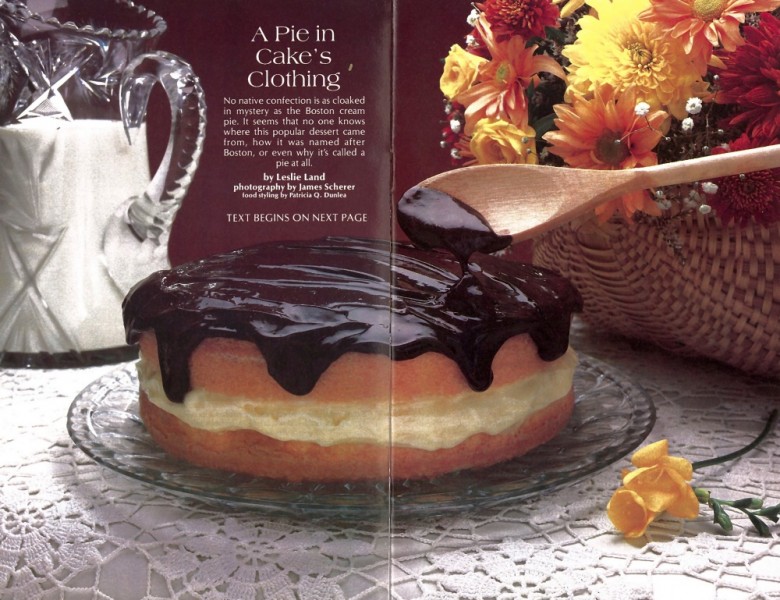

No native confection is as cloaked in mystery as the Boston cream pie. It seems that no one knows where this popular dessert came from, how it was named after Boston, or even why it’s called a pie at all. Curious about the history of Boston cream pie? Read on.

Photo Credit : James Scherer

Never was there a more enigmatic piece of pastry. To start with, as almost everyone knows, it isn’t pie — it’s cake. Plain old American butter cake of the purest ray serene — not a trace of crust in sight. There’s a bow to trifle in the custard filling — but only Puritans would content themselves with such a small amount of custard.

For another thing, no one seems to have invented a story for how this strangely named cake came to be. Boston’s Parker House has long taken credit for just calling the thing “Boston cream pie,” but whatever possessed them to do it they have never seen fit to tell. Even Evan Jones’s respected American Food reports that although Boston cream pie has been on the menu at the Parker House since the day it opened, “the fact that it is really a cake disguised by this misnomer remains unexplained.”

It’s a safe bet, however, that all the ancestors of Boston cream pie were made with sponge cake or pound cake. “My father used sponge cake. The old-timers used rich sponge cakes even for birthday cakes,” said Donald Favorat of Nelson’s Bakery in Malden, Massachusetts, who’s Boston cream pie recently got a rave review from the Boston Globe. The moist, buttery cakes that form our layer cakes today are a relatively new phenomenon in the world of pastry. They became possible only after baking powders were developed in the 1870s and 1880s, and were not part of widespread commercial baking until highly emulsified shortenings were available in the 1930s.

Mr. Favorat told us that he routinely makes his Boston cream pie from a “high-ratio” cake with lots of sugar and shortening in proportion to flour and eggs. He then ventured his opinion that the real secret of the pastry is in the custard filling. Sensing we were finally on to a critical piece of inside information about Boston cream pie, we pressed him for his recipe. Alas. Because fresh cream and eggs, although delicious, are among the most unstable and easily spoiled substances known to man, Nelson’s bakery uses an imported Danish filling base called Creamyvit, available only to the trade and in lots of 50 pounds or more. (We forebore asking what’s in Creamyvit.)

So what is Boston cream pie? We were as far away as ever. It is usually remembered as a special treat, something you got when you were out at a restaurant — fancy dessert that always came from a store, not a home kitchen. As a Maine fisherman friend of ours put it, “Regular pie — apple, blueberry, stuff like that — we had every day, but Boston cream pie ..,” His eyes took on a faraway look, as did the eyes of most of the men asked about the subject. Women, on the other hand, mostly said they could live happily without it.

Thus Boston cream pie leaves us with one more mystery: how did this particular pastry become a gender-specific pleasure? Answer that one and you win the cream pie.

If you want to attempt to duplicate that store-bought or restaurant-created Boston cream pie of your childhood dreams, the following recipe will at least take you in the right direction.

BOSTON CREAM PIE RECIPE

For the Cake:

1 3/4 cups sifted cake flour (sift before measuring)

2 teaspoons baking powder

1/4 teaspoon salt

6 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons solid vegetable

shortening (such as Crisco)

3/4 cup plus 1 teaspoon sugar

3 egg yolks

2 teaspoons vanilla

3/4 cup milk

Have all ingredients at room temperature. Preheat the oven to 375°. Butter two 8-inch cake tins and line the bottoms with wax paper.

Thoroughly combine the flour, baking powder, and salt. Cream the butter and shortening until they are fluffy, then slowly beat in the sugar. Beat until the mixture is again very light and fluffy. Rub a dab between your fingertips — the sugar should be almost completely dissolved. If the mixture feels gritty, beat it some more. Beating thoroughly at this stage is important if you want a light-textured cake.

When fats and sugar are thoroughly creamed, add the egg yolks one by one, beating thoroughly after each addition. Beat in the vanilla.

Measure out the milk in a pouring pitcher so you can add it in two parts. Beat a third of the flour into the batter, then half the milk, then flour, milk, flour. Be sure each addition is thoroughly mixed in before you add the next, but do not beat any more than necessary.

Divide the batter between the pans and smooth the tops. Bake for 10 minutes, then reduce the heat to 350° and bake 10 to 15 minutes more, or until the cake is browned and a toothpick emerges clean. Invert the layers onto wire racks, peel off the paper, and let cool.

For the Chocolate Icing:

2 squares (2 ounces) unsweetened chocolate

1 tablespoon butter

1/2 cup granulated sugar

1/4 cup condensed milk

1/4 cup light cream or milk

1 teaspoon vanilla

In a small pan or double boiler, melt chocolate and butter over low heat. Blend in sugar, condensed milk, and cream or milk. Cook until thickened. Remove from heat; beat with a spatula or wooden spoon until cool. Blend in vanilla: Spread the icing on the prettiest layer. There will be a little icing left. Save it to drizzle down the sides of the finished cake.

For the Cream Filling:

1 1/2 cups milk

1 vanilla bean (small)

1/2 cup sugar

5 egg yolks

1/4 cup flour

1 tablespoon (1 envelope) gelatin

2 tablespoons cold water

1 cup heavy cream

3 egg whites

4 tablespoons sugar

Split the vanilla bean to expose the seeds. Put it and the milk in a saucepan over medium low heat and cook only until small bubbles appear around the edge of the pan. Allow to cool.

In a separate, heavy, non-aluminum saucepan, beat the 1/2 cup sugar with the egg yolks until well combined, then beat in the flour. Cook, stirring, over very low heat, until it starts to thicken. Pour in the milk in a thin stream, beating all the while. Add the vanilla bean.

Cook, stirring, until the mixture is so thick it holds the path of the spoon. (It will do nothing for quite a while, then suddenly stiffen up, so don’t go wandering off and forgetting to stir or you’ll get wicked lumps.)

Soften the gelatin in the water, then stir it into the thickened custard. Be sure the gelatin is completely dissolved, then turn off the heat. Stir from time to time as the custard cools to release steam that would thin it.

When the custard has cooled, chill it. While it’s chilling, beat the cream until it forms soft peaks. Beat the egg whites until they start to thicken, then slowly add the sugar. Keep beating until you have a shiny meringue that forms slightly stiffer peaks than the whipped cream.

By now the custard should be starting to set. Snatch it from the refrigerator and beat in the meringue. As soon as that’s incorporated, remove the vanilla bean and fold in the whipped cream.

Again chill the filling until almost set — a matter of a few minutes only.

Put the bottom cake layer on a serving platter. Pile on the filling and spread it to within an inch of the edge. Apply the iced top layer, pressing gently to spread the cream.

Chill the cake until the filling is completely set — at least 3 hours, and gobble it up within the day.

Excerpt from “A Pie in Cake’s Clothing,” Yankee Magazine, January 1983