The Artist in Winter | Eric Aho

Painter Eric Aho at work in Walpole, New Hampshire.

Photo Credit : Rachel Portesi

Photo Credit : Rachel Portesi

On a bright Sunday morning in January, artist Eric Aho drives down from his home in Saxtons River, Vermont, crosses the Connecticut River to Walpole, New Hampshire, and heads uphill to a pond at the edge of an apple orchard.

He parks his van by a small log building. Pulling out long steel chisels and an ice saw, he sets them on the deep porch by the building’s front door. He walks back for a telescoping easel; a paint-splattered canvas bag heavy with jars of linseed oil, tubes of oil paint, and brushes; and a bin stuffed with towels, a wooden bucket, soap, and rubber slip-on shoes.

Aho has just returned from New York City, where a show of his work recently opened at the DC Moore Gallery. The show follows two acclaimed exhibits in New England in 2016, at the New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut and at the Hood Museum in Hanover, New Hampshire.

The attention is not new. His paintings hang in major art museums in the United States and around the world. Some collectors are 20 pieces deep into his oeuvre. He is becoming known for a series of monumental works that have drawn comparisons to European and American masters of landscape painting and modernism. The paintings—luminous landscapes of ice—explore the boundaries of realism and abstraction, presence and absence. They have established the 51-year-old Aho as New England’s preeminent artist of winter, at a moment when the future of winter itself is uncertain.

He walks onto the pond and bounces on his feet a couple of times. Even in a season of little snow, with midday temperatures spiking into the mid-50s, winter is holding firm in at least one respect. Overnight lows have dropped far enough that all around the valley, ponds are frozen solid. The ice is thick enough to hold.

Layers of meaning and loss lie below the surface.

I’m a third-generation Finnish-American,” Aho says. For an artist of winter, it helps to have a heritage from a northern land, even if the heritage is hyphenated.

Aho’s grandparents emigrated to the United States from rural Finland in the early 20th century. They left a homeland where polar night blankets the land for almost two months in the third of the country above the Arctic Circle. Finns have learned to endure the cold by meeting its extremes with their own. In sauna, a custom that reaches back into prehistory, Finns bathe together in small buildings heated by a wood-fired stove. When they can no longer stand the heat, they immerse themselves in a “plunge pool”—avanto, in Finnish—cut into the ice. Over millennia, the tradition has created a culture with an intimate connection to, even an affinity with, winter.

Still, Aho’s grandparents knew well that cold kills. A famine in the mid-19th century touched off what Finns would later call the Great Migration. Matti Aho, Eric’s grandfather, was born in the years immediately following the famine. He came to the United States at the height of Finnish flight, hoping for a better life in a new country.

Matti and Amanda Aho settled in Townsend, Massachusetts, one of the small, heavily Finnish communities radiating out from the industrial city of Fitchburg. The area’s forests, glacier-scoured granite, and deep ponds—and climate—reminded the immigrants of the land they’d left behind. The Ahos shopped at a Finnish Union Cooperative in Fitchburg, banked at a Finnish-run bank, and read a Finnish-language newspaper published in Fitchburg. Their youngest son, David, along with many of his classmates, spoke only Finnish until he started school. He would later tell his son Eric, “I grew up in Finland in America.”

Photo Credit : courtesy of the author

Eric Aho, though, grew up feeling more shame than pride in his heritage. In 1974, when he was 8 years old, his family moved to Hudson, New Hampshire, just beyond “Finland in America.” The move came at a difficult time for Eric’s family and for the country: Nixon was about to resign, the war in Vietnam was coming to its divisive end. Local kids, thinking Aho was an Asian name, taunted Eric and his younger brothers and smashed the family’s mailbox. David Aho had worked for Boston & Maine Railroad since returning from World War II; increasingly, his work was interrupted by labor disputes between his union and the railway.

Eric and his father regularly visited aging members of the Finnish-American community. They’d bump along back roads past tree farms, fields grown up in sumac, barns falling in on themselves, while David Aho told stories from his childhood. They’d turn off a dirt road and roll up to a farmhouse and sit at a kitchen table. The adults would pour strong black coffee into saucers to cool it, and hold sugar cubes between their front teeth to drink it. Eric ate thick, warm slices of cardamom-spiced coffee bread. Small talk, usually in Finnish, broke long silences.

Eric knew enough of the language to sense from those spare conversations that the move to America had been hard, and perhaps regretted. Around the kitchen tables, he would hear the old-timers say, “Finns are buried in the back of the cemetery,” a statement that seemed to distill both the pain of the outsider and the suspicion with which the outsider was viewed.

In those conversations, his grandfather was said to “sleep behind the woodstove,” and Eric guessed that Matti Aho had been a heavy drinker. The phrase suggested why many of his father’s favorite memories revolved around a teetotaler neighbor, an easy-humored farmer who brought young David along on winter ice harvests and helped him find his way around machines and tools.

David Aho, in turn, taught his son the value of tools. Eric learned to handle axes, pikes, and come-alongs. He went with his father on small logging jobs, sharing labor and few words. “Aho men work with their hands,” his father would say, and Eric could hear the pride in his voice.

All the same, Eric got the impression that his father hoped his son would make his living in other ways. As a kid, Eric drew detailed pictures of motorcycles, snowmobiles, Great Danes—things he desired but could possess only through his drawings. His parents supported his decision to attend Massachusetts College of Art, where, he quips, “working-class kids like me go to learn graphic design.” He studied printmaking, which can be both trade and art. He also became a student of art history. He thought that he might make his living using the tools of art.

Photo Credit : Rachel Portesi

“I didn’t realize it was OK to be Finnish,” Aho says, “until the Putney School.” After graduate studies, he took a job teaching art at the southern Vermont boarding school. He picked up the fundamentals of oil painting alongside his students. He painted his first winter scene outside, en plein air, like Monet, working to capture light and weather directly as he observed it.

That Aho would explore winter in his art struck his colleagues as entirely natural, given his heritage. They knew about saunas and assumed he was an expert Nordic skier. It was the first time someone outside the Finnish community had shown an interest in his background. He rather liked being an “ambassador” of Nordic culture.

At age 25, Aho received a Fulbright fellowship and traveled to Finland for the first time. He painted, met his father’s cousins, and made friends who invited him to saunapäivä, or “sauna day.” He learned about the place of saunas in Finnish culture, their design, even that Finns were often born and prepared for burial in saunas. He left the country more keenly aware of the tradition’s intimate connection to the cycle of seasons and human life.

Eric Aho was still at Putney when his father was diagnosed with cancer, in 1995. During his final months, David Aho visited antiques stores, seeking out tools he’d used over a lifetime. Eric sometimes went with him. The trips took them back in time and memory, to those back-road drives when Eric was a boy and his father told stories from when he was the same age as his son, especially about joining his neighbor in the ice harvests on Lake Potanipo. Decades later, his descriptions retained a child’s sensory vividness.

He remembered the steel chisels and jagged saws the Finnish farmers used to cut the blocks of ice, the piercing whistle of a steam locomotive, fingers numbed by the cold, the salty taste of fish bones in black Finnish coffee; himself as a wide-eyed child nestling into the tangy warmth of draft horses; as a boy edging in from the margins, finding a way to be useful by sharpening saws; as a broad-shouldered young man holding his own with the older workers and putting money in his pockets. “That was a good day,” his father would say.

Eric helped care for his father during the last weeks of his life. In the hours before he died, David Aho labored to tell his ice harvesting stories one last time: the comforting smell of horses, men speaking Finnish, train whistles, the saws in constant need of sharpening. It occurred to Eric that his father was seeing a world in full, one that Eric could not join.

He felt cheated, and hurt. This was what his father, in his final moments, had chosen to give him? These worn-out stories? This was his inheritance?

Aho was 30 years old when his father died. Two years later, a pair of New York City collectors bought several of his paintings. Their checks totaled more than Aho’s annual salary as a teacher. He thought of the risk his grandfather had taken in coming to a new world, and decided to gamble himself: to leave teaching and make a living by his paintbrushes.

He was also starting a family of his own. Friends encouraged him to build a sauna at the edge of their orchard in Walpole for saunapäivä. Finnish acquaintances traveled to New Hampshire to help him raise it in a rough, “farm” style. His grandfather could have stepped inside and believed he was back home.

The first time Aho cut an avanto outside his sauna, he found himself unexpectedly plunged into the world his father had described on his deathbed. He was pulled in by the weight of the tools, the action of cutting through the ice, the shape of the hole. It was an unanticipated connection—the avanto had nothing to do with harvesting ice—but once made, it drew him deeper. He had questions about his father’s experiences on the ice, but his father was not there to answer them.

He turned instead to research, and discovered deep connections between his father’s threads of stories and New England’s winter history.

A century before Matti Aho sought a new life in America, Frederic Tudor had gambled on frozen water. Around 1804, the young Bostonian had the fantastical notion that fortunes could be made by cutting ice from ponds near Boston and shipping it as a luxury item to residents of the colonial West Indies. For two decades, Tudor lost money on the “frozen-water trade.” His cargo melted. His ships sank. He was jailed for debt. But in 1825, he hired Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth to manage his ice harvesting operation on Fresh Pond in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Tudor’s ship came in.

While Tudor focused on selling ice to wealthy colonials in the tropics, Wyeth set about improving every tool and systematizing every process in the ice industry. Wyeth’s first invention was the “ice-plow,” which combined the farmer’s horse-drawn plow and the carpenter’s plow plane, and allowed ice harvesters to mark out any body of frozen water and extract uniformly shaped blocks of ice. Wyeth devised pulleys and platforms to raise ice blocks out of Fresh Pond, designed better icehouses to store them in, and invented a horse-driven conveyor belt to put them there.

Tudor, the visionary, and Wyeth, the modernizer, together transformed a seasonal task, done routinely but according to individual inclinations, into a highly efficient, mechanized commercial industry. They turned something ephemeral into a product.

Aho discovered that the Fresh Pond Ice Company left its namesake pond in 1890 after the citizens of Cambridge became concerned that commercial ice operations were contaminating their water supply. Under new owners, the company moved to Lake Muscatanapus in Brookline, New Hampshire. Muscatanapus was said to be a Native American word for “great mirror.” The lake was also known by another name: Potanipo.

The ice harvesting that David Aho joined as a young boy had changed little from the days of Nathaniel Wyeth—horse teams still pulled ice-plows, men chiseled and sawed the ice into blocks—but on Potanipo it operated at its zenith. A dozen icehouses six stories high under a single roof ran 1,000 feet along the lakeshore. Hundreds of men worked the harvest. “Endless chains” drew 800-pound slabs of ice out of the water, ice planers cut them to a standard depth, and stevedores slid the finished cakes into compartments within the icehouses. Articles about the operation invariably mentioned its hypnotic motion and its fascinating geometric patterns. By sheer happenstance, David Aho participated in the greatest ice harvesting operation the world has ever seen.

Wyeth and Tudor had succeeded beyond their dreams in establishing a national desire for winter’s ice year-round. The U.S. had become the first country in history to enjoy ice “not as a luxury for the rich,” notes British historian Gavin Weightman, “but as an everyday necessity.” Within a short time, however, the very definition of year-round ice changed. Like pond ice at the end of winter, the natural-ice trade thinned, became full of holes, and then simply disappeared.

By the 1930s, consumers considered manmade ice more reliable and safer than natural ice, and each year they bought more of the new electric refrigerators. Toward the end of David Aho’s time harvesting ice on Lake Potanipo, its famous icehouses emptied and then sat unused, as the ice was by then being loaded directly onto trucks. In 1935, the icehouses burned to the ground. Two years later, David Aho helped with the lake’s final harvest. He had also witnessed the industry’s demise.

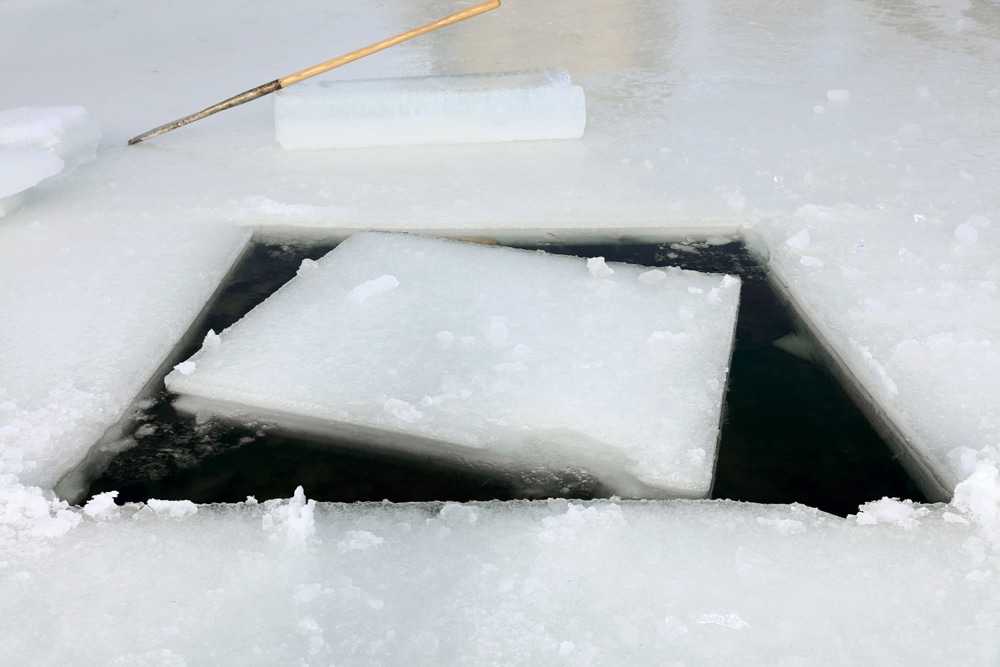

On the orchard pond, Eric Aho gently lifts the saw out of its wood-and-leather cover. He found it in a barn in New Hampshire, in perfect condition, the same vintage as the tools his father had used. He carries the saw and one of the chisels onto the ice and places them on a towel next to the ghost of a previous avanto.

He etches a rectangle into the ice with the chisel’s square, beveled blade and extends the lines past the corners. He chips out one line at a corner, widening it, then carefully inserts the blade of the long saw through the ice. Rocking slightly forward and back, he draws the saw toward him.

Photo Credit : Rachel Portesi

Ten years after his father’s death, Eric Aho was sitting on the sauna porch on a sunny winter day not unlike this one. In the years after leaving Putney, he’d become known for his sweeping landscapes of the Connecticut River Valley. He and his family had moved up the road to Saxtons River; he’d rented studio space there in the gym of a former orphanage, the Kurn Hattin School for Girls. Occasionally he packed paints and canvas along with the sauna tools on saunapäivä and set up facing west, painting the view across the river. More often he sat on the sauna porch, cooling down, and simply looked out over the pond.

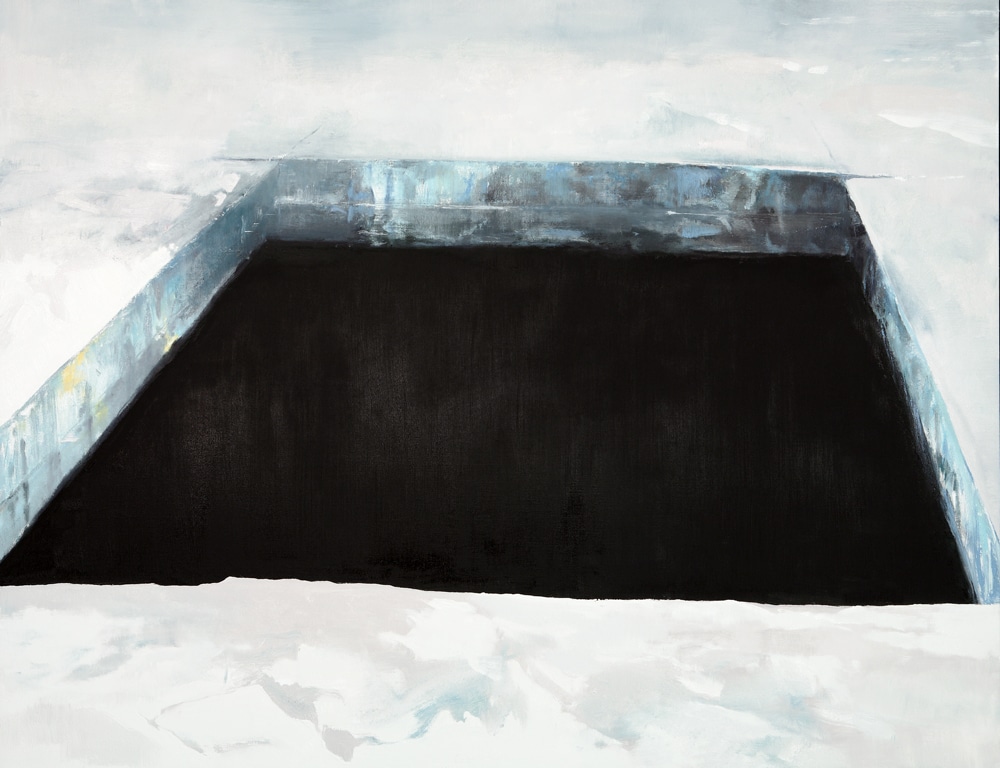

That day, however, his gaze rested on the hole he’d cut in the ice. He noticed, for the first time with a painter’s eye, the extreme contrasts of light and dark in the watery rectangle surrounded by ice. In the water itself, he saw intense greens, yellows, turquoise—a kaleidoscope of colors. He thought, This might be the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

Photo Credit : Rachel Portesi

Back in his studio, Aho worked from memory, reframing the scene as if he stood on the far side of the plunge pool, the broad river valley dropping away beyond the snow-covered pond, winter clouds massing overhead; the avanto, a dark rectangle, anchoring the painting’s bottom edge. The landscape revealed a personal commentary on loss and disappearance. He drew on his father’s ice harvesting stories, his father’s death, the ineffable connections he felt to his father when he cut through the ice. He called the painting Ice Cutter.

Photo Credit : Rachel Portesi

When Aho returned to the sauna the next winter, he looked more closely at his avanto. He studied where he had scored the ice, marking the intersections of lines at the corners of the trapezoid. In the studio, he moved in closer to the hole as well. The view across the valley disappeared, along with any hint of horizon, the pond now merely implied. He enlarged the black hole to the size of the actual avanto and tilted it upright. The black shape dominated the canvas.

The avanto in Aho’s new painting was still discernible as a hole in the ice, but what had been part of a scene became an independent shape, separate from landscape. He called it Ice Cut and immediately started another. Aho realized that he had embarked on a series. He’d been thinking about decades: how turning 40 marked 10 years since his father’s death; how his father’s years at the ice harvest coincided with the Depression. He made a plan to paint an Ice Cut each year for a decade.

He decided to give each painting two dates: one for the year he painted it, and the other, in parentheses, from one of his father’s seasons on the ice, a date that also gave Aho multilayered sources of inspiration. He drew from his father’s fragmented stories and also from what was happening in the world, and in modern art, during that parenthetical year. He imagined his father and remembered himself at the same age. As his son entered the same season of life, Aho thought of him, too.

With each new Ice Cut, Aho felt his art become more personal and layered with meaning, but also—for a working artist—more risky. He watched people respond very differently, often viscerally, to the paintings, even before they knew what they were looking at. A big, black rectangular hole. Some recoiled, as if from the void: death, loss, emptiness. A question hangs over this saunapäivä —whether any of the Ice Cuts in the New York show will actually sell.

Among the critics, there is no question about Aho’s achievement. Christopher Volpe, writing for Art New England, said of the show at the Hood Museum, “[T]he series offers a rich, sustained meditation.” For The Boston Globe’s Sebastian Smee, it was “a major accomplishment.”

Most years, Aho has made not one but three or four Ice Cut paintings, living with winter throughout the year. At some point, looking at Monet’s snow scenes, he was struck by the thought that the great artist had painted winter as a tourist.

In his most recent works, growing bolder, Aho has experimented with color, refracting through memory the kaleidoscopic hues he saw the first time he looked at the avanto as an artist. He’s painted it in the yellows of an arctic summer, in tropical turquoise and aquamarine, in sizes even larger than life. He is not ready to stop. “I feel like I’m just now scratching the surface,” he says.

He comes to it, again, on this January afternoon. He sits as long as he can in the 200-degree sauna. Walking out into the sharp winter air, he steps out of his sauna shoes and onto the towel at the edge of the avanto. Steam rises from his skin. He lowers himself to the edge, swings his legs into the freezing water.

The questions he had asked himself after his father’s death would remain unanswered, but he was coming to a clearer understanding of what he had inherited.

He had been given a distinctly northern sensibility and a vantage on two cultures half a world apart. His father’s stories had animated a deeply personal and creative exploration. Through the tools of his art, he had met the extremes of winter with extremes of imagination and created a lasting legacy.

Aho will end up selling a dozen pieces as a result of the New York show: one to a museum, the others to private collectors. Ice cut from New Hampshire, once more a luxury, will again bring winter into distant homes.

But it wasn’t ice that Aho was harvesting: It was ice’s absence, the void left when ice is no longer there. The loss is not an abstraction. A century ago, ice removed from Lake Potanipo was routinely two feet thick; in the past few years, locals say, it’s been only half that.

Other questions hang over saunapäivä. As the earth continues to warm, what will it mean to be northern? What will it mean when natural ice is no longer a common, everyday part of the landscape for our grandchildren? What tools—what extremes of imagination—will be needed to color that future inheritance?

Aho pauses almost imperceptibly. The black hole represents what is lost, the past, the gap between what is real and what cannot be known. It represents the path and the leap.

He puts his palms flat against the ice, pushes off, and takes the plunge.