Becoming Mikaela

With 60 World Cup wins and three Olympic medals

in less than a decade, Alpine skier Mikaela Shiffrin at 24 is arguably the most dominant athlete in sports.

Photo Credit : Heather McGrath | Illustration by The Sporting Press (AP Photo/Giovanni Auletta (Mikaela portrait) Doug Mills/The New York Times/redux (Mikaela with flag))

Spectators along the Dartmouth Skiway’s steepest trail have cinched up their hoods or turned their backs to the bitter wind as they wait for the race to start. Volunteer course workers are struggling to keep the giant slalom gates upright. Funnels of snow spiral across the slope just as the first forerunner appears at the crest of the final pitch. Instantly, I feel my pulse spike, which makes no sense at all, because I’m just a bystander at this children’s ski race—a qualifier for the New Hampshire state championships for 10-to-13-year-olds.

The competition gets under way, and one after another, girls in colorful ski suits whiz by, some in aerodynamic tucks, some in decidedly less streamlined positions. Parents and siblings shout encouragement; some are ringing cowbells, World Cup–style.

“What number are they on?” a woman near me asks. After she gets an answer from her companion, I hear her say, “I feel like I’m going to throw up.”

I have to smile. I remember that feeling. More than a decade ago, I was a ski racing mom with a pounding heart and a crumpled start list in my gloved hand, standing with no doubt equally overwrought parents in the cold and blowing snow. We’d tuned the skis, risen at dawn, checked the forecast, packed the lunches, lugged the gear, found the lost goggles, activated the hand warmers, offered the Kleenex, tightened the helmets, then—in whiteouts and in polar vortexes—we’d skied or hiked or snowshoed to the sidelines to wait for that singularly agonizing moment when our child was about to push out of a starting gate and point his or her skis downhill. Sure, we’d signed our kids up for the local ski club so they would have fun, make friends, and learn a lifetime sport. We loved skiing and hoped they would too. And we all assured each other that the results didn’t matter—even as we silently entreated the stopwatch gods to grant our sons or daughters a top 10 finish or, if that was too much to ask, at least please not let them fall. I mean, we got it: These were weekend races in small-town New Hampshire. It wasn’t like any of these kids were going to the Olympics.

Except, hold on a second. Maybe one of them was.

Back in 2003, when my daughter Claudia was 8 years old, a new girl joined her group on the Ford Sayre ski team. At the time, I was a co-director of the volunteer-run ski racing program, which was an outgrowth of a community ski school started in Hanover, New Hampshire, in the 1930s by Dartmouth alum Ford K. Sayre. My job entailed, among other things, going to monthly board meetings and handling sign-ups. This new registrant, who had moved to rural Lyme, New Hampshire, from Vail, Colorado, had a sweet smile, a thick braid, and a snazzy red and black ski jacket. She also had a mother (a Western Massachusetts native and champion on the over-30 masters ski race circuit, we heard) who acted as her unofficial coach, shadowing her on the snow during the team’s five-times-a-week practices. The mother was at her side on weekends at the Dartmouth Skiway, the club’s home hill in Lyme, which had challenging-enough terrain to have hosted the 2003 NCAA Skiing Championships, and on weekdays at the after-school sessions held at mom-and-pop Whaleback Mountain, set along Interstate 89 in Enfield, or tiny Storrs Hill, on the edge of downtown Lebanon, which had one single-rider Poma lift.

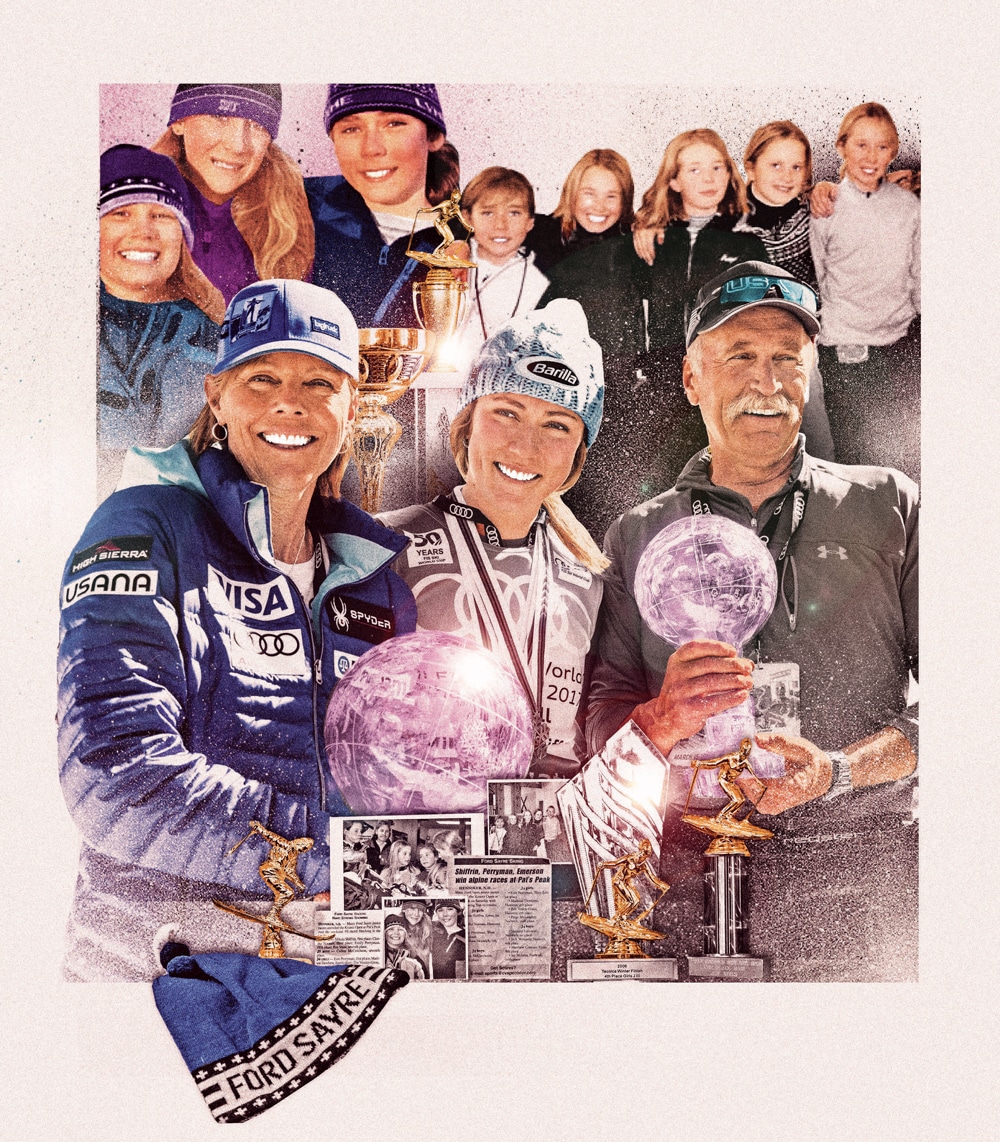

Photo Credit : Heather McGrath | Illustration by The Sporting Press | Doug Mills/The New York Times/redux (Shiffrin family); courtesy of Meg Lukens Noonan (Archival photos)

No matter the venue, when it came to skiing this new girl was all business. When other kids were clowning around in the terrain park, she was analyzing turn apexes. When other kids were sliding on cafeteria trays on a slope near the base lodge, she was rehearsing pole plants. When other kids were chomping through boxes of pre-race Milk Duds, she was calmly preparing to eat their lunch on the slalom or giant slalom course. Which she did. Every single time.

She was a lovely girl, as I recall—polite and humble and friendly. She didn’t set herself apart, but she was most definitely apart.

Her name was Mikaela Shiffrin.

In just nine years, she would win her first World Cup race—and be on her way to becoming one of the best ski racers in the world. Her accomplishments in this most capricious of sports, where mere fractions of a second can separate the top finishers, are astonishing. Last winter, at the age of 24, she won a record 17 World Cup races, bringing her total number of career victories to 60. She also became the first skier—male or female—to win the World Cup overall, slalom, giant slalom, and super-G titles in a single season. Not only that, but in 2019 she earned her fourth consecutive World Championship gold in slalom. And, oh yes, in her two Olympic appearances (2014 and 2018) she won two gold medals and a silver. A phenom, a prodigy, a once-in-a-generation talent, the best ever—she has been called all of these things. That she was in our midst for a few years before her family moved on was both thrilling and confounding.

“Without a doubt, Mikaela was the most polished 8-year-old I had ever seen,” said Mark Schiffman, who has coached for Ford Sayre on and off since 1988 and had Shiffrin in his training group. “She looked like a mini World Cup racer. And she was deceptively fast. Her skiing was so smooth, it was not immediately obvious how much faster she was than other kids.”

She didn’t just beat my daughter and all the other girls in her age group; her times were often significantly better than those of boys who were bigger, stronger—and several years older.

“It was so impressive, the way she stood on her outside ski. She was so well balanced,” said veteran Ford Sayre coach Matt Purcell, recalling the first time he saw Mikaela. “She was doing things as an 8-year-old that most kids didn’t start to learn until years later. That came from a lot of hours on snow.”

Naomi Tomky, now living in Seattle, was a college sophomore who had just quit the Dartmouth ski team when she was asked to help out as a part-time coach for the Ford Sayre team.

Photo Credit : Heather McGrath | Illustration by The Sporting Press

“My first day on the hill, I watched Mikaela, and I said, ‘Holy crap, she is awesome!’” Tomky remembered. “I had no framework for this—I’d just started coaching—but I remember thinking that if no one screws this up, she will be a world-class racer. And I felt pressure not to be the one to screw it up.”

It wasn’t Mikaela’s technique alone that impressed the coaches. It was also her sunny attitude, her focus, and her commitment to hard work. Beyond that—and perhaps most baffling to those of us who had learned that a parent’s optimal level of on-mountain involvement was to be the person at the bottom with the snacks—Mikaela didn’t just tolerate the near-constant input from her mother, Eileen, but seemed to welcome it and thrive on it.

“Instead of getting fed up and turned off, Mikaela listened and did what her mother asked her to do,” said Mike Holland, a two-time Olympian in ski jumping, a parent to three racers, and a coach in the Ford Sayre kids’ jumping program. “That approach typically doesn’t work. I’ve seen many pushy parents [over the years]. The motivation needs to come from the kid. You can’t maintain it without a passion for it.”

Purcell recalled that after the day’s program ended at 1 p.m., Mikaela would be back out with Eileen at 1:30, doing more laps and drills. “The bottom line was that Mikaela wanted to be out there. She had that inborn passion. And her parents instilled an incredible work ethic in her.”

Sometimes I spotted Mikaela and her mother on the trail below as I rode the Skiway quad chairlift with other parents. Eileen might be demonstrating hand positions or pointing down the fall line or following closely behind her daughter shouting instructions. Helicopter mom. Too much. Over the top. I’m sure we said those things. But there was awe, too, and the sense that we might be witnessing something much bigger than our homegrown club, something so lightning-in-a-bottle special that conventional wisdom was off the table. We all felt it—the kids, the parents, the coaches, and, I think it’s safe to say, Eileen herself. I remember her sitting on the edge of a table in the base lodge one day, telling me about a conversation she’d had with Mikaela. They’d been driving home from the Skiway, and Mikaela, who was in the back seat, had asked when the next race was. As I recall it, Eileen said that when she told her, Mikaela said she couldn’t wait to have that feeling again—of pushing out of the gate and flying down the course. And she had said it with such unexpected intensity, such ardor, that Eileen had studied her in the rear-view mirror and wondered just what she had on her hands.

Long after Mikaela left us and rose to prominence, we learned through profiles in TheNew York Times, The New Yorker, and Sports Illustrated, among others, that the Shiffrins’ unconventional, hands-on approach had extended well beyond the slopes. Eileen and her husband, Jeff, an anesthesiologist and former member of the Dartmouth ski team, were voracious consumers of videos, books, and articles about ski racing technique. They subscribed to the theory that 10,000 hours of deliberate practice was required to master anything, and so they looked for ways for Mikaela to log skills-building time. Balance was deemed crucial, so the Shiffrins bought a unicycle. Coordination and focus were vital, so Mikaela was encouraged to practice juggling. (She was occasionally spotted on the streets of Lyme juggling while riding a unicycle.) Mikaela and her brother, Taylor, who also skied on the Ford Sayre team and went on to race for the University of Denver, simulated skiing on in-line skates and made slalom turns around broomsticks. Chores such as rebuilding the front lawn, as the family did one summer, weren’t just a matter of pitching in; they also developed upper-body strength. Every activity was another stone laid on the path toward what the Shiffrins said was the goal: not to make the podium, but to make the perfect turn.

By all accounts, Mikaela had been a gung-ho participant, embracing challenges, soaking up information—and clamoring for more. Beyond supreme talent, she seemed to have “a rage to master,” a trait identified by Boston College psychology professor Ellen Winner as one of the defining characteristics of highly gifted children. That she also had parents eager and equipped to be the bellows to her fire made Mikaela a prime candidate to grow into the world-beater she became.

—

Eileen’s role as a de facto coach to Mikaela and several other girls who had started trailing along with the duo rankled Ford Sayre coaches. Parents weren’t supposed to be on the hill with their kids during practice—we all knew that—and they sure weren’t supposed to be offering advice. Hoping to bring Eileen into the fold, the team asked her to become an official coach.

“I remember being shocked that they brought her on as a coach,” said Tomky, “because it was the opposite of how things worked on the teams I had been on as a racer—a parent overstepping their bounds would have been banned from the hill, not invited on board. I recall thinking it probably had to do with it being a very small town; everybody would still have to run into each other at the grocery store.”

No one questioned Eileen’s coaching skills. She had a keen eye for what kids needed to work on. She could be generous with her time with racers who were serious about improving—and she was excellent at conveying advice. (She even taught my daughter, who got a little banged up in a fall, how to swallow ibuprofen—something I’d failed at for years.)

“She is probably one of the best coaches you’ll ever meet,” Purcell said. “And she did bring good things to Ford Sayre.”

Her strong opinions, however, often ran counter to traditional coaching protocol. She believed, for instance, that even young racers should learn how to use their forearms and shins to bang slalom gates out of the way, an advanced technique that coaches generally didn’t introduce until later. She kept Mikaela and her small training group doing drills when free-skiing was encouraged. It wasn’t long before a rift developed in the parent ranks. Some saw Mikaela’s results and questioned why all of the coaches—including head coach Tiger Shaw, a two-time Olympian, nine-time U.S. national champion, and parent of three Ford Sayre racers—weren’t doing what Eileen was doing. (In 2014, the year Mikaela won her first Olympic gold, Shaw moved to Park City, Utah, to become CEO and president of the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association, the governing body for the U.S. Ski Team—a head-spinning convergence of Ford Sayre alumni.)

Seeking even more training time for Mikaela, the Shiffrins joined a second team, the Lebanon Outing Club, based out of Storrs Hill, which offered night skiing and was so small that skiers could get in more than two dozen runs in a single practice session. A handful of Ford Sayre families followed them there. They wanted some of Mikaela’s magic dust, even if all they got to do in the end was eat it. That caused more turmoil on our team; you weren’t supposed to ski with two clubs at once.

At our monthly board meetings, we wrung our hands over the Shiffrin situation. I don’t remember the details of the discussions, but I do remember leaving a few of the gatherings in tears. I was a volunteer, a mom, a maker of snacks; I wanted no part of this drama. Eventually, Eileen was relieved of her Ford Sayre coaching duties, and the Shiffrins switched their affiliation to the Lebanon Outing Club. By the winter of 2007, they had left the area—first moving to Burke, Vermont, then back to Vail, then returning to Burke when Mikaela was old enough to enroll in the Burke Mountain Academy, a small boarding school for elite ski racers. In some interviews about their years in New Hampshire, the Shiffrins don’t mention Ford Sayre at all.

“I hope Mikaela remembers us,” Purcell told me. “I hope she appreciates the work that all of us put in. I’m sure she does.”

Ford Sayre certainly remembers her.

“All the kids idolize her,” Purcell added. “And she’s a great role model for them. You don’t see temper tantrums if she doesn’t win. She doesn’t throw stuff. I say, ‘She was a great kid with a big smile on her face, just like you guys.’ And I tell them, ‘If you want to get better, you have to be very dedicated.’”

Photo Credit : Heather McGrath | Illustration by The Sporting Press

I asked him if any current members of the Ford Sayre team show Mikaela-like potential.

“We have a couple who are on the fringe, and if they keep on the right track…” he said. “But it’s a long road and things change. It’s such a tough sport. It takes a lot of things going the right way. You cannot replicate how Mikaela became Mikaela.”

—

Under the high beamed ceilings of the Dartmouth Skiway base lodge, families have gathered to wait for the announcement of the race results. I’ve settled at a table near a group of preteen girls, their faces flushed with windburn, who have strewn the table with jackets and helmets and gloves. Some are dipping French fries into plastic containers of ketchup; some are popping Skittles. A few are looking at phones. I ask them who their favorite racer is and they look up, all smiles.

“Mikaela!”

“One of my daughters was in her age group when she skied for Ford Sayre,” I say.

“Whoa,” they say.

“What have you heard about her?” I ask.

“On a powder day, most kids would go ski in the woods, but she would set a course and train,” one girl volunteers.

“She stayed after practice to do drills until she got it right, and even when she got it right, she’d keep skiing.”

“She would train, eat mac and cheese, train, go home, and then go train more.”

“The coaches always have us write our goals down for the year, and when Mikaela did hers, she said she wanted to win a World Cup race.”

“It’s kind of cool to know you can actually get that far from here.”

“Super-far,” another girl says. They all nod.

I finish my hot chocolate and look around the crowded lodge, remembering these long afternoons. It always took forever for results to be announced. We wanted to get going. We were tired. It would be getting dark soon. We had to let the dog out. I don’t miss all the waiting around. But I do miss the camaraderie of the other parents, we anxious sideline boosters who were bonded by the million things it took to get our kids to a ski race and by the pleasure of seeing our sons and daughters grow to love skiing as much as we did. I also, perhaps surprisingly, miss those drives home from the Skiway, from Sunapee, from Ragged, from Gunstock. On serpentine back roads, under a twilit sky streaked purple and mauve, my husband and my daughters and I talked—not about who had won (duh, Mikaela), but about friends and school and life. In the end, being the fastest wasn’t the point—not for my kids, not for most kids.

Still, when I see Mikaela Shiffrin on television sliding into a World Cup starting gate, goggles down, breathing deeply and deliberately, staring down the racecourse in the wind or fog or swirling snow, my heart rate soars.

—

Where Olympians Are Made

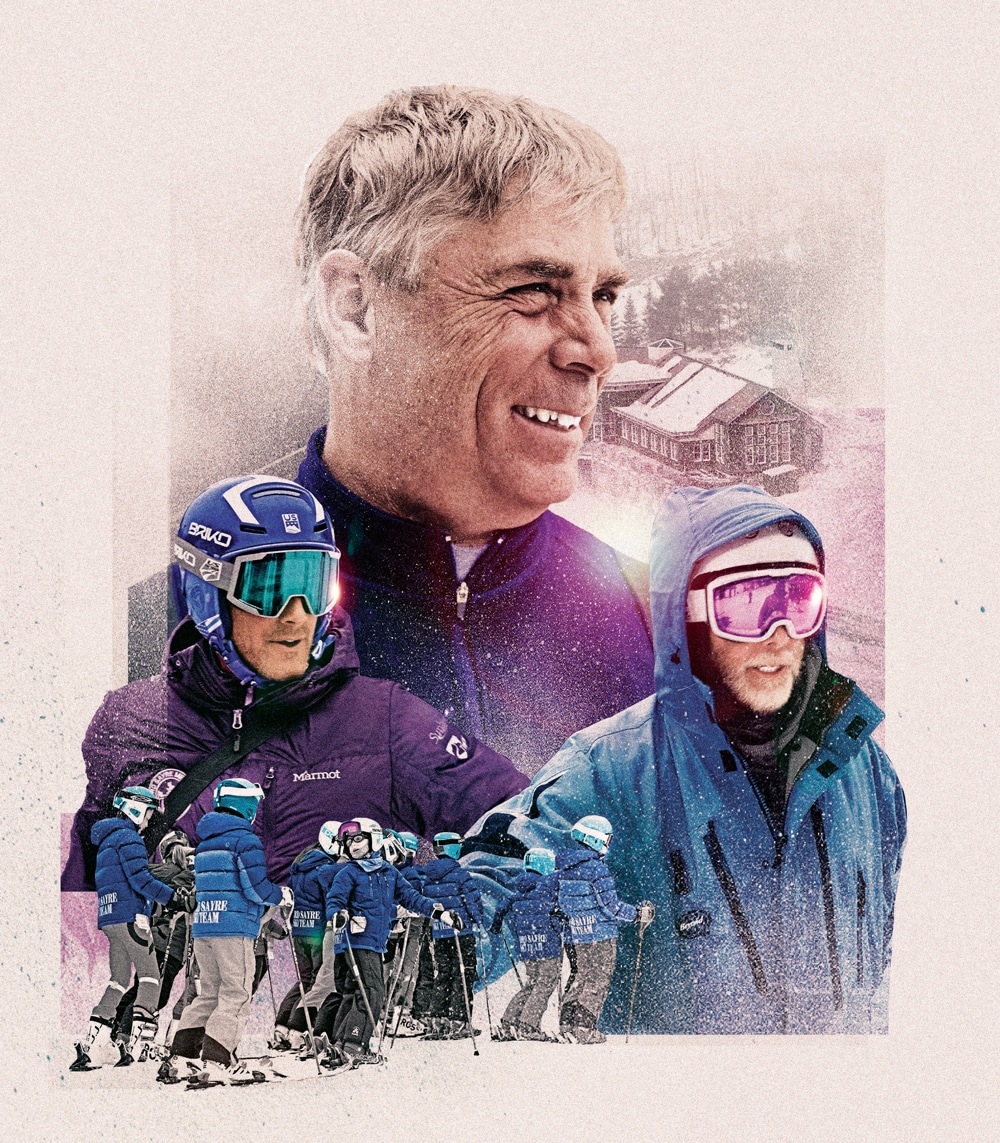

Mikaela Shiffrin is not the first Olympian to have roots with the Ford Sayre Ski Council. The organization, which offers kids Alpine, cross-country, freestyle, and ski jumping programs, as well as an intensive “academy” for highly committed high schoolers, has sent more than a dozen athletes to the Winter Games since its inception in 1950.

The council was formed to carry on the work started by Ford K. Sayre and his wife, Peggy, who were the managers of the landmark Hanover Inn in the 1930s. Ford had fallen in love with skiing while attending Dartmouth (as a senior in 1933, he’d directed the school’s famed Winter Carnival) and believed every child should have the chance to learn the sport.

Photo Credit : courtesy Norwich Historical Society

The Sayres gathered and refurbished used equipment and gave free ski lessons to area children. In the gentle hills of Hanover and neighboring Norwich, Vermont, boys and girls trudged up beginner slopes, their breath visible in the sharp cold, and made their first joyful descents. With progress, students could graduate to Oak Hill in Hanover, where the country’s first J-bar lift was installed in 1935.

Ford joined the Army Air Corps in 1942. Two years later, at the age of 34, he died in a midair collision during an air show in Spokane, Washington. In his honor, friends raised money to keep the Sayres’ ski school going. By 1956, the program had not only introduced hundreds of local children to skiing and ski jumping but also produced its first Olympians (and Sports Illustrated cover subjects) in Ralph Miller of Hanover and Betsy Snite of Norwich. Snite went on to win the Olympic silver medal in slalom in 1960 at Squaw Valley, California.

The Hanover region’s deep affinity for winter sports, coupled with accessible venues that allowed kids to ski and jump after school—not just on weekends, as with most ski teams at bigger ski resorts—created a perfect incubator for budding champs. At the same time, elite athletes—some homegrown, some products of Dartmouth (which itself has sent more than 100 athletes to the Olympics)—who settled in the area supplied a deep gene pool of talent. Many of those local stars enrolled their own children in Ford Sayre programs and often volunteered to coach.

Among the Ford Sayre alums who have competed in the Olympics are Walter Malmquist (1976; Nordic combined), Jeff Hastings (1984; ski jumping), Mike Holland (1984, 1988; ski jumping), Dorcas DenHartog-Wonsavage (1988, 1992, 1994; Nordic skiing), Joe Holland (1988, 1992; Nordic combined), Felix McGrath (1988; Alpine), Jim Holland (1992, 1994; ski jumping), Liz McIntyre (1992, 1994 [silver], 1998; moguls), Tim Tetreault (1992, 1994, 1998; Nordic combined), Hannah Kearney (2006, 2010 [gold], 2014 [bronze]; moguls), and Paddy Caldwell (2018; Nordic skiing).