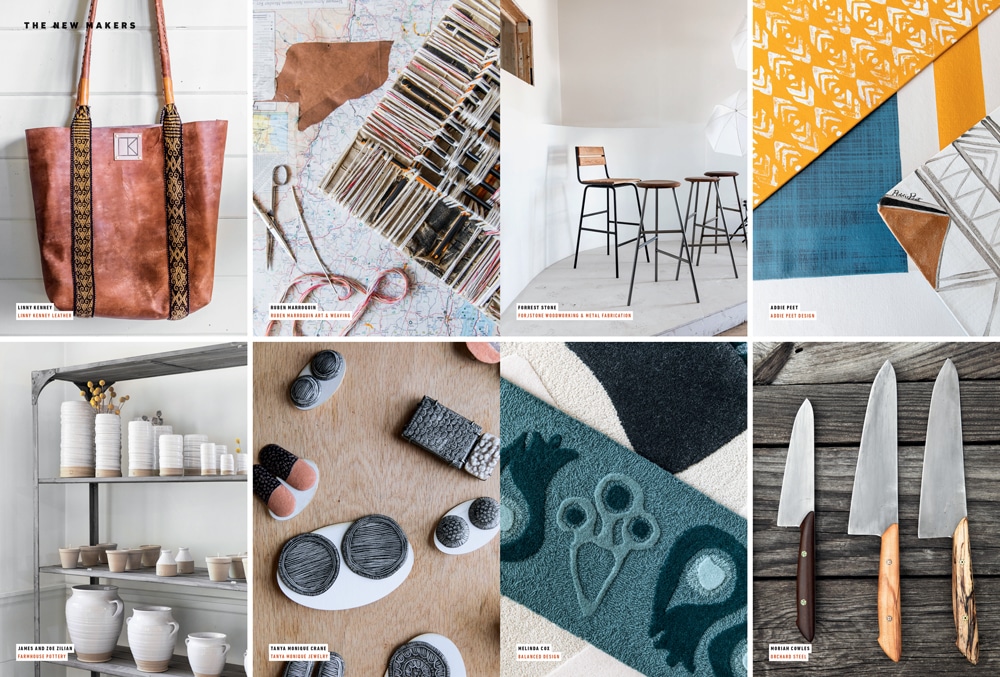

The New Makers of New England Heirloom Crafts

Linny Kenney

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Forrest Stone Forjstone Woodworking & Metal Fabrication | Portland, ME

A raised garage door marks the entrance to Forrest Stone’s 2,000-square-foot workshop, a warren of rooms jammed with equipment. Each area is carefully delineated: metal, woodworking, painting, photo studio. In the past, Forrest gained a reputation for crafting tables and chairs he describes as “Shaker meets midcentury modern,” meaning lean and elegant. But if you’ve come to admire his previous work, be prepared for the unexpected.

Out here in the hinterlands of Portland, far from the bustle of Exchange Street or Munjoy Hill, this woodworking metal fabricator is dreaming up custom fixtures for the city’s high-profile foodie and brewery attractions: the counter at the Holy Donut, for instance, or the powder-coated aluminum bar at Battery Steel Brewing. It’s also possible you’ve lounged on one of his 68 wood-and-steel barstools—handcrafted beauties with the grace and balance of Calder mobiles—that are scattered around the city.

That said, when talk turns to taprooms and breweries, Forrest lights up. He’s fast making a name up and down the coast for his work in this arena, playing with purge lines, building stairs to a koelschip (a kind of fermentation vessel), and constructing large wooden vats called foeders that are used in Europe but almost impossible to find in the U.S. “It’s more fun than making a live-edge table for a millionaire,” he says with a grin. “Instead of making a static object, these are in the service of another art. And the frontier for metalworking feels limitless.”

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Addie Peet Addie Peet Design| Winterport, ME

There’s something a little bit prairie about Addie Peet. Maybe it’s the homesteading feel of the house that she and her husband, Noah, built in 2016 in a carved-out circle at the far end of a dirt road in Winterport. The small, shingled building, all 560 square feet, rises from the land like a sturdy pinecone.

The attached studio where Addie makes her contemporary painted floorcloths, however, is something else entirely: sleek, industrial, twice as big. So maybe there’s some urban hipster scrambled in too. Not literally—this Maine native grew up in Camden, and for decades her family operated a boys’ summer camp—but more stylistically. With her horn-rimmed glasses Addie gives off a serious air, yet there’s an undertone of whimsy, a complexity that finds its way into rug designs such as Indigo Dye, which seems tie-dyed onto super-thick canvas, and Coastal Stripe, layered to create depth in each stripe.

“It was a lost art,” she says of her initial interest in floorcloths. “I kept wondering, ‘Why can’t you find these anywhere?’ I got into it as an intriguing hobby.” That was 10 years ago, when she started experimenting with the same canvas her family once used to make camp canoes. It took two or three years before she turned out a rug she would put her name on, because “I wanted to make something that would last forever, that would stand up to dogs, mud, snow.” Addie points to an 8-by-11-foot floorcloth sitting on a massive worktable, explaining that when a rug is this big, she will actually climb on top of it as she works. “It was harder when I was nine months pregnant.” Definitely prairie.

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

James and Zoe Zillian Farmhouse Pottery | Woodstock, VT

Lucky chickens: free-range and they get to drink from Farmhouse Pottery. These fortunate fowl live in a picturesque coop tucked into the elbow of a vaguely Scandinavian-looking building on the outskirts of Woodstock. “We put a lot of love into it,” says Zoe Zilian of the 1954 former Bible bindery on the Ottauquechee River that she and husband James bought and rehabbed nearly four years ago. Today, instead of Bibles, it’s stocked with the elegant pitchers, cheeseboards, and dinnerware that have gained a following among high-end chefs, foodies, and even the likes of Scarlett Johansson, who recently stopped by.

“I was the kid who was immediately good at it,” James says of his “obsession” with clay. “I started in sixth grade, and never really stopped.” Married 15 years, the Zilians were “always making things,” says Zoe. After living in New York City and then Boston, they settled here to raise their daughters. “I thought it would be nice to have him throw some pots,” she remembers. James resurrected an old style of European studio pottery, then modernized and refined it. “It’s our own recipe,” he says. “We were after durability—we wanted people to use [what we make].”

Customers can watch that recipe spinning into a hypnotic mix of crockery at the hands of skilled potters in the attached studio, using clay mined in Sheffield, Massachusetts. At the end of the day, each handcrafted pot is stamped with a signature laurel wreath. Says James, “We’re practicing artistry with a blob of mud and centrifugal force.”

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

John WelchJohn Francis Designs | Lowell, MA

In a former fabric mill on one of Lowell’s historic canals, you can practically hear the creative hum. Three hundred artists are tucked away in the Western Avenue Studios, the largest artist community on the eastern seaboard. Tantalizing hints of talent are strewn about the endless corridors, with murals, sitting nooks, and even a brewery to distract.

But step inside John Welch’s woodworking studio, and there’s an instant feeling of focus. The warm scent of wood hangs in the air, a preamble to sinuous wooden spoons, serving boards, and dark dishes carved of walnut. A handful of these projects fill his massive workbench, which once served the shop class at a public middle school in Lowell. “There’s a good chance I worked on this very table,” John says, running his hand over the surface. “I’ve always been a tinkerer.”

On this day, much of the bench is occupied by an outsize serving board, a special commission for a chef in Boston. Four shallow “bowls” are carved into the seamlessly joined slabs of polished walnut; the wood seems melted together. “I like doing spoons,” John says, “but I love doing one-of-a-kind pieces.” Lately, he’s getting more chances to do just that, thanks to the food photographers, chefs, and stylists who are drawn to his clean, unfussy look.

He picks up a chunk of raw wood and shows how the almost childishly rough outline of a spoon has been drawn on. Soon he’ll select from his rack of tools—gouges, hooks, carving knives, chisels—and begin the slow process of carving … removing everything that isn’t a spoon.

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Jeremy Frey Jeremy Frey Baskets | Eddington, ME

Jeremy Frey’s hands rarely stop weaving, but there are exceptions. Once, he takes a break to explain the intricacies of a custom basket, its black latticework climbing the sides of a tightly woven body. And later, amid ash logs in the garage next to his basement studio, he shows how to whack a tree with the blunt end of an ax, battering every inch to loosen and strip the layers of fiber that will one day sit curled in his studio, waiting.

Raised in Passamaquoddy Indian Township, near the Canadian border, Jeremy learned to make baskets from his mother, Gal Frey. “Growing up, I always did art,” he says. “Our toys were pencils, paints, clay. I had my own jackknife when I was 5.” As he got older, he says, “I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life, except I wanted to be an artist. At 21, my mother said, ‘Why don’t you weave some baskets?’”

With seven generations of weavers in his family, it seemed inevitable. Then he got fierce about it. “I wanted to do what no one else had ever done with baskets.” His first show, in 2002, sold out. Since then, his work has won just about every prize that can go to a basket.

Unlike his grandfather’s sturdy utility baskets, Jeremy’s own pieces are called “fancy.” It feels like understatement. A Jeremy Frey basket swoops and curls, like music rendered in ash wood and sweet grass. “I like to do baskets that look one way from a distance and completely different when you’re up close,” he says. “A whole other world inside.”

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Tanya Monique Crane Tanya Monique Jewelry | Pawtucket, RI

There is nothing shy about Tanya Monique Crane’s jewelry. Discs of woven sweet grass converge in a cluster as big as a breastplate; a fist-size knot of oblong baskets dangles around the neck. She calls these oversize pieces “wearable art,” and indeed they’re a dramatic synthesis of sculpture and jewelry. “When I work, I’m thinking about the travels I’ve done, where I’ve moved, mixing in different perceptions,” she explains.

Tanya’s studio in a onetime Pawtucket creamery bears signs of percolation at every workstation: metalsmithing, enameling, kiln firing. The hand tools are tiny, delicate, perfect for working on production pieces such as her black-and-white full-moon earrings flecked with hieroglyphs. These showcase a technique called sgraffito, where she scratches away black paint to reveal the white enamel beneath. “That’s the fun part, sitting making tick marks,” she says. “I’ve already planned it, so it’s very meditative, very Zen.”

A professor at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, Tanya has described her work as existing on the threshold “between prejudice and privilege.” And for her, it was always jewelry, right from the start, beginning with a metalsmithing class in 2001. She indicates a pile of rusty shards—crumbling chunks of commuter rail stairs—that are destined for transformation into something strong and beautiful for a solo show in January. “The first fiber mill in America was in Pawtucket,” she says. “I’m looking at the buildings, the black history, the slave crafts that traveled through this area. I’m looking at the remnants, things falling apart.” The shards are mottled, coppery and black. “It was always a mystery—metal.”

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Linny Kenney Linny Kenney Leather | Littleton, NH

If you’re the kind of person who likes to stick your nose in a baseball mitt for that deep whiff of leather, you’ll love Linny Kenney’s leatherworking studio. Or if you dream of living in a whitewashed tree house, you’ll appreciate her second-floor aerie overlooking the Ammonoosuc River, its windows lined with red geraniums.

But if you’re the sort who dreams of riding your horse across the country for eight and a half months (as Linny did in 2010, with tack she made herself), playing guitar as you ride, then you’ll feel deep kinship—even before you’ve had a chance to take in the rugged leather knife rolls, Japanese design–inspired aprons, and bags trimmed with Peruvian cintas that Linny travels to remote villages to find.

Linny’s strong and nimble artwork draws on basics learned from her stepfather, a leatherworker in the ’70s. That strap that tethered her guitar as she rode her horse across the miles? It’s decorated with her first-ever drawing-on-leather: a portrait of her grandfather, holding her as a baby. It’s the same strap she uses when she slings on her guitar for a night of singing with her band at Schilling Beer Co. in downtown Littleton. The knife rolls alone are good reason to sing.

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Ruben Marroquin Ruben Marroquin Art & Weaving | Bridgeport, CT

Follow the threads of a life, and you’ll discern a tapestry. For Ruben Marroquin, that tapestry weaves across continents, from Chicago to Caracas, Mexico City to Paris, and finally to Bridgeport’s Arcade Mall, built in the 1840s and topped with a soaring antique-glass atrium. Along the way, the threads have made a bold pattern, encompassing everything from teaching weaving workshops for children to creating textiles, scarves, and ultimately the 3-D artwork that cascades across his studio walls. “I’ve struggled to name it,” he admits of his wrapped canvases. “It involves embroidery, yarn, silk, and hard materials [such as] bottles, bamboo, random objects. It’s not really fiber art—it’s more like fiber sculpture.”

As a kid, Ruben studied painting, but it was in art school in Caracas that his interest took a sharp detour: After running out of paint one day, he began making textile collages instead. Later, in Guatemala, “in search of my roots,” he fell in love with the weaving he saw on the streets. It led to design school in New York and time spent at the École Nationale Supérieur de Création Industrielle in Paris (where he was, he confesses, “more interested in learning to speak French”).

His workspace is filled with voluminous beauties, woven pieces that have caught the eye of designers and publications such as Architectural Digest. But Ruben clearly still loves teaching children, too, with the evidence on display in his studio window. “I’ve done so many kinds of work,” he says, “but it has jumped to something very personal, a sculptural approach that’s very earthy.” He flashes a smile. “I don’t ponder the theories behind it. I’d rather just make it, and then figure out what I’m doing.”

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Moriah Cowles Orchard Steel | Shelburne, VT

Behind the iconic red farm stand at Shelburne Orchards, and relegated to a corner in a sprawling barn, sits an anvil and a forge no bigger than a breadbox. Moriah Cowles, a bladesmith, calls the forge “Frankenstein”; its patches look stitched-on, almost cartoonish. Nonetheless, it works just fine, heating up to a toasty 2,000 degrees. Proof of its efficiency is close at hand: carbon steel cut and hammered into the shapes of primitive knives. She’s been forging her own knives since 2009. “I have this steel down,” she says, her ropy arms a testament to the demanding craft that she has studied with masters from Mexico to Brooklyn.

In the barn, it’s nearly impossible to envision the elegant blades she’ll finish off in another workshop nearby: polishing the metal, matching each knife to its handle (black walnut, lilac, apple wood, among others), and stamping the blade with her maker’s mark. When there’s enough inventory, she will hold an online lottery—an offbeat approach to selling that allows her to make the knives she chooses, rather than filling custom orders, with time left to manage the family land that her grandfather bought in the 1950s. “I love the art of utility,” says Moriah. “Making something creative with a purpose.”

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Melinda Cox Balanced Design | Pawtucket, RI

“It starts with Sharpies,” says Melinda Cox, which is a funny thing to hear in this high-ceilinged studio dotted with artful fabric swatches and midcentury couches covered in bold yellow flowers. The massive 1889 textile mill that engulfs this little design oasis is stark proof of Pawtucket’s prominence in the Industrial Revolution. How ironic that it now houses a textile designer whose fabrics are the antithesis of mass production. And that simple Sharpies are at the root of bold patterns inspired by Calder, Rothko, and bird feet.

The impetus for Balanced Design—named for eco-friendly materials and good design—sprang from the tragedy of 9/11. “I went to Paris right after that,” Melinda says. “I remember sitting on a park bench, noticing how people were bringing their own bags for groceries, cars were smaller, how environmentally friendly Europe was.” It inspired her to begin making organic cotton pillows with splashy wool felt appliqués. “I was one of the first to make environmental products that weren’t beige,” she laughs. The pillows took off.

In 2008, Melinda hit her stride with pared-down, hand-drawn designs that continue to employ local talent. Her silkscreens are made at a Rhode Island textile mill; pillows are sewn in Fall River, Massachusetts. “I used to accompany my mom to the textile mills in North Adams,” she says. “This resonates. I’m connecting directly with my past.”

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus