The Joy of Bottle Hunting

Why do old bottles fascinate us so? Wayne Curtis recounts his Maine bottle hunting adventures.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanBy Wayne Curtis

Sitting on my dining room table is an empty glass bottle that once contained Tab soda from … I don’t know, the 1970s? It’s currently one of my favorite bottle finds—I saw its nubbly neck sticking up from under fresh leaves last fall in the woods about a quarter mile from my house in Maine. In fact, I found several buried together like the terra-cotta army interred with the first emperor of China. I liked the design and heft of these bottles. And they reminded me of my childhood, and of the metallic-sweet taste of Tab—Coke’s distant cousin, a cola that was familiar but spoke in a hard-to-place accent. I use these bottles today to store sugar syrups for cocktails and the odd salad dressing.

But I also like the Tab bottles because they remind me of one other fact: I’m not a bottle collector. No bottle collector—and they are legion—would keep one of these in their collection. Tab bottles are too new, too common, too elementary. It would be like someone claiming to be a book collector, then showing off shelf after shelf of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books. I probably couldn’t sell a Tab bottle for a quarter. So I’m definitely not a bottle collector.

Although in truth I do have a few more bottles—a box or two in the attic, and a few high on shelves here and there. But it’s really more of a casual hobby, like doing the occasional jigsaw puzzle on a rainy day rather than having a full-blown obsession. And, as mentioned, these bottles are quite practical for use around the house.

One’s route to becoming a bottle hunter is often rather simple: One finds a bottle. Better still, one finds a bottle dump behind one’s house. It’s not as if you found treasure. But a bottle has value because you found it. One discovery leads you to want to make another one. And then another one.

For more than two decades, I’ve spent summers in Grand Lake Stream in eastern Maine, at a cabin on a lake at the edge of a village of fewer than 100 year-round residents at the end of a 10-mile road. In the 1890s, the town became a vibrant outpost for anglers. Sporting camps and dozens of modest cabins cropped up around the lakeshore, many of them on land that was then owned by the timber company but leased to employees. Paper mill workers retreated here for fishing and hunting and would spend part of the summers with their families. My cabin was built in 1952, and when my wife and I bought it in 1997 we were the third owners. I’ve spent every summer here since.

The forested landscape here can feel pretty primeval. One gets the sense that the glaciers only recently receded, leaving gray, spalling rocks and pine duff that winter winds have brushed into the spaces between them. Hemlocks and pines and maples grow between and on top of the boulders. The woods around my camp are not fit for growing much of anything, except teaberry and mushrooms.

I found my first bottle dump a few years after moving in. It was a year of mushrooms—chanterelles were flourishing after steady rains—and I was in search of them. A few dozen yards from the lakeshore, I heard underfoot a flinty, crunching sound. I dug around with my toe and discovered that I was walking upon an esker of rusted tin cans. Then I saw the glint of a bottle neck emerging from the duff a few feet away. I dug around with my toe a bit more—most of the glass here had been broken. I imagined that this was the work of kids tasked with taking out the garbage, and smashing bottles on rocks was their chief reward. But some bottles were intact. Some had been on their sides for the better part of a century, and had become informal terrariums, with mosses and evidence of previous insect habitations. I preferred to think these had once been occupied by beetles who couldn’t believe their luck that they’d stumbled upon a crystal cavern of unimaginable grandeur.

The first bottle I brought back to the house was a broad-shouldered rectangular bottle embossed with “J.R. Watkins Co.” The typography was both clunky and charming. Online research turned up the fact that the J.R. Watkins Company was founded in Minnesota in 1868, and this was a bottle that contained vanilla extract.

The bottle is pretty sizable for vanilla—it holds 10 ounces. When I ran into one long-time villager at the store, I told him about my find and how people must have loved to bake around here, and I posited that perhaps they were very fond of pound cake. He laughed. “No,” he said, looking at me as if I were dimmer than he’d previously imagined, “that’s what people drank. They drank it during Prohibition, and then they drank it afterward so they could deny they had a drinking problem.”

I’ve since brought back many more bottles, cleaned them up and used them. I stash them in the attic with the bottles I’ve bought at the occasional yard sale. Did I fail to mention that sometimes I buy bottles at yard sales? Well, I do. That still doesn’t make me a collector. For instance, I have yet to look up the value of a bottle.

Since I was curious about bottle collectors and what compulsion kept them drawing into mosquito-infested woods, I did some Googling around, which led me to Walter Bannon. He lives in southern Maine, and so I called him up. He told me he got interested in bottles growing up in Mystic, Connecticut, living near a man who had a basement filled with old bottles. One day Bannon was invited in for a tour of the collection. “That really piqued my curiosity,” Bannon said. “Everybody has a little bit of a treasure hunter in them. And I thought, if he can be a treasure hunter, what’s stopping me?”

Bannon searched out old bottles around his home in Connecticut, and he continued his habit even after pursuing a career in telecommunications. He lived on Block Island for a time, where he found a bitters bottle from the 1880s buried in the sand. He then moved to Maine and kept searching for old bottles, often combing the margins between railroad tracks and forest. He once found a bottle embossed with an earlier spelling of the town of Bridgton, Maine—“Bridgetown”—which made him realize these glass vessels could contain a lot of history. Some bottles have giant bubbles in them, indicating they were handblown. “That bubble holds the DNA of the early glassblower,” he said. “It really does hold history.

“Even the shape of a bottle tells a story,” he went on. “Or there might be the name of the pharmacy on it.” One of his favorites has an image shaped like a kidney and is embossed with “The Great Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp-Root Kidney Liver & Bladder Remedy.” “This was a quack cure,” he said. “It probably had a little bit of whiskey and some maple syrup in it.” He appreciates it for the art and the folklore behind it.

Within a couple of years of moving to Maine, Bannon had filled every shelf in the house. “And from there it started to spiral,” he said. “That’s when my wife got a bit nervous. She said either I go, or the bottles go.” He’s pretty sure she was joking, but just in case, he started a bottle show with another collector to pare down his collection. But not enough. Eventually he set up a five-room bottle museum in Naples, which he manned three days a week, moving most of the bottles out of the house. He operated that for four years, but then he closed it not long ago. “I wanted to get back to my original love of the hobby—the search,” he says.

Over the decades he moved from scouting along railroad tracks to looking in rivers—an earlier artery of commerce. He took scuba lessons to be able to scour the bottoms of rivers to find what long-ago passengers and boatmen tossed overboard. He says he’s turned up some great finds, including an intact pottery jug from the 1820s on which a bird was painted.

Bannon also liked the peacefulness of being deep underwater, of sinking down into the quiet of a stream with only the sound of bubbles rising to the surface. “My favorite memory was going into the Saco River and finding a hole about 20 feet deep,” he recalled. It was filled with bottles and stoneware. “I started looking around and it was like being in an antiques store, and everything was free.”

Bannon, who is 68 and retired, is known around town as “the bottle guy” or “Mr. Bottle.” (At least one person was surprised to learn that his last name wasn’t actually Bottle, he said.) One of the hazards of being a known collector of bottles is that people are always dropping off unsolicited bottles they find in the basements of relatives. Bannon mostly gives these away, or at least he strives to. He brought a few boxes to the town dump a while back and left them by the swap shack. Within a couple of days, they were back on his doorstep with a note from someone suggesting that he might want these.

I have not yet reached a point where the townspeople leave me tribute. But I like old things, especially when they prove useful. A few years ago I ordered a bag of corks in random sizes to fit the bottles I find. Last year I turned up a box of bottles I’d forgotten about—and who among us has not found a box of bottles they’d forgotten?—so I cleaned them up, made cocktails for friends, labeled them, corked them, and delivered them as gifts. The bottle is yours to keep, I insisted with a tone of mild menace, which seemed a way to make room for other things. This has mostly turned out to be more bottles.

Like Bannon, I also enjoy the treasure-hunting aspect. When I go tramping in the woods I don’t expect to find something, but when I do it’s like finding a $5 bill in a parka you put away last spring. I especially like to search for bottles late in the day, when the sun slants under the trees and turns the forest a pale gold, making the silvery glimmer of glass all the more notable.

Part of the reason I’m drawn to old bottles is their heft and sense of permanence. I often marvel that they are in the same family as plastic bottles. In contrast to those gossamer-thin-walled water bottles that are very loud and crinkly when empty, old bottles are stolid and silent. That’s especially true of a J. Gahm & Son beer bottle from the 1890s I turned up one day when scrounging for driftwood in a remote cove favored by loons. It’s stout and heavy and could serve in a pinch as a war club. I imagine the guide paddling a canoe to shore to cook a lunch of landlocked salmon, while his sport smoked a cigarette and drank the beer he’d brought along before blithely tossing the bottle into the underbrush. Try finding a plastic bottle that can tell you a story like that.

A couple of summers later, across the lake at the mouth of Whitney Cove, I was poking around in the woods when I heard that telltale crunch of rusted tin beneath pine duff. I soon unearthed a cache of embossed Log Cabin Syrup bottles that I’d guess were about a century old. There were a lot of them. Sitting on a mossy rock, I gave this some thought and decided this was the site of an old logging camp, where the loggers subsisted chiefly on flapjacks and off-color stories. If not for those bottles, this spot would be just another piney still life with warblers.

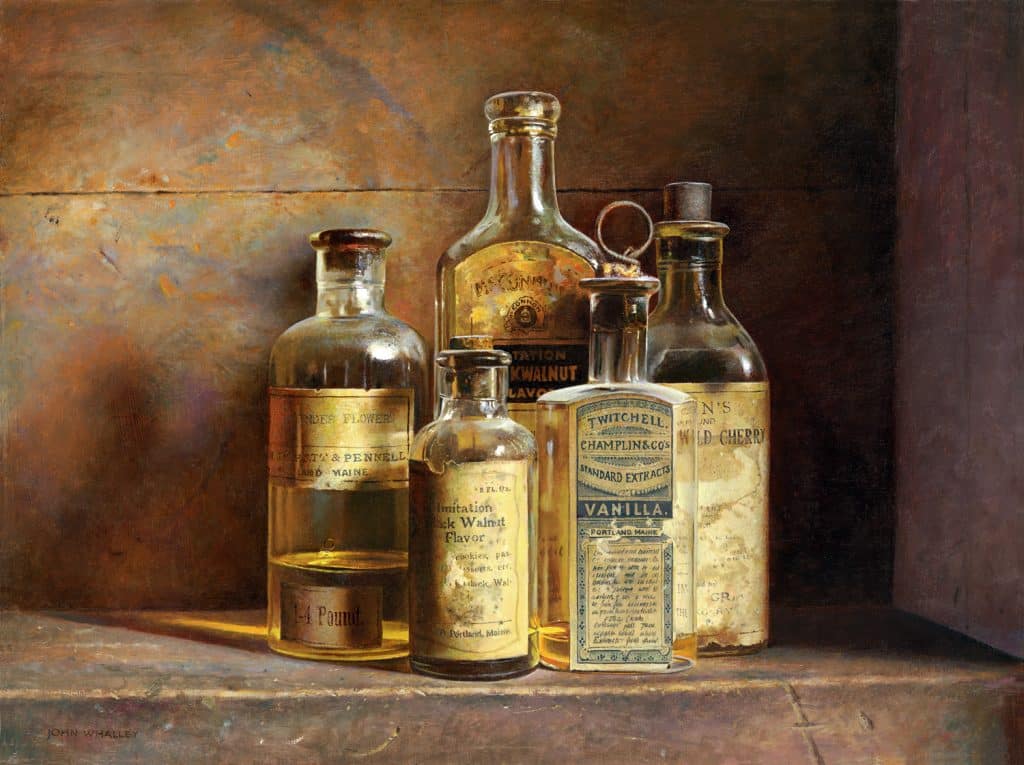

John Whalley

Last summer I decided to explore along the three-mile waterway that connects two large lakes at Grand Lake Stream. Anglers over the past 125 years have spent hours waist-deep in frigid water, and it occurred to me this might provoke a thirst for something with horsepower. And when bottles are empty, would it not be easier to toss them in the woods rather than carry them back to one’s camp a distance away? So, I started walking along the stream, following a path approximately one bottle’s toss from the water’s edge.

And that led to a curious discovery: I found four bottles, apparently from the 1970s or so. Each was still firmly capped—and this was a first for me—partially filled with whiskey. Maybe it started to pour rain and they had to leave suddenly. I don’t know, but it was a bit eerie, and I kept looking over my shoulder, as if someone would come for them. I left them there but came back the next day with a tasting glass. And I learned something else: Whiskey buried partially underground for decades doesn’t hold up all that well.

This past spring, I visited the National Bottle Museum in Ballston Spa, New York, about two hours from the Vermont border. It was hardly out of my way, and I’m sure you, too, would detour a few hours to see two stories of old bottles. The National Bottle Museum is, in fact, the number one attraction in Ballston Spa, according to the website TripAdvisor. “I have driven by forever and never bothered to stop because frankly who cares?!” began one five-star review. “I have never seen somebody so enthused about bottles my entire life,” wrote another reviewer.

The museum is housed in a former downtown hardware store, and I found it both fascinating and not. I learned a lot about how bottles are made, including their evolution from wooden molds to metal ones, and how “slug plates” were used to emboss the bottles with names. That was the interesting part. The less fascinating part was the bottles themselves. Not that they weren’t great—I especially liked the black-light display of the bottles made with uranium, and the cobalt-blue poison bottles—but the sheer quantity was just too much. Shelf after well-curated shelf of interesting bottles, from floor to ceiling.

I realized what I like about discovering bottles one at a time in woods or at a yard sale is that they each tell a story about a place and a time. Here, hundreds of them were all crammed together in well-lit, glass-fronted cases. They all yammered at once and I couldn’t make out any of the stories—it was like being in a room of loud and tipsy conventioneers, and soon I had to go find a place to lie down.

It’s free to visit, but if you donate $5 or more you get a mystery bottle wrapped in tissue paper. I actually got two empty whiskey mini bottles, which I will add to my collection. Did I say collection? What I meant is that I’ll put them in a box at the back of a closet.

A little while ago I started to feel like I was strip-mining the woods of its history without putting anything back. What will be left for future generations to find? So last summer I decided to start my own bottle dump in the woods. I’ve been writing about cocktails and spirits for nearly two decades. A side effect of this line of work is that I get liquor samples shipped to me regularly. These come from both major manufacturers and small craft distillers. And there’s been an interesting escalation of elaborate bottle design in the past decade or so. Some liquor now comes in old-school-style bottles (think of the Bulleit whiskey bottles), while others are more innovative and eye-catching, including from distilleries you probably haven’t heard of, like Peerless Rye and Chattanooga Whiskey.

For years I’ve been recycling bottles when empty. But that was just throwing away history, I realized. I was depriving someone not yet born of seeing the glimmer of a bottle neck in the woods and extricating it from the leaves and glimpsing what were the boom times of the early 21st-century distilling world.

So, I started setting aside the better bottles, the ones with embellishments and embossing, and every few weeks I’d take them up the hill behind the house and deposit them near a large glacial boulder. I’d place them such that the openings are facing down, so that they won’t fill with rainwater and breed mosquitos and crack during a winter freeze. Also, I want to make sure beetles could find their way in and luxuriate in the crystal splendor and warmth of the fall light. Yes, mine is a curated bottled dump—some might dismiss it as an “artisanal dump.” But I don’t mind. After the leaves cover them over and countless winters pass through, someone in the distant future will find them and pull them out and peer into the abyss of the past, and will marvel, if just for a minute.

Why, these bottles may even be valuable treasures by then—strange objects to those living in an era when everyone will no doubt be drinking out of nanofiber bladders sutured to their bodies or some such thing. These bottles could actually be worth a lot of money. How much? Hard to guess. You should probably ask a bottle collector.