Find Indoor Inspiration at These Five New England Museums

Banish the winter blahs at five New England museums whose settings are as engaging as their artworks.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanEscape the winter chill by exploring five New England museums that offer more than just captivating art. From maritime treasures to immersive exhibits, these destinations offer something for everyone, whether you’re an art aficionado or just looking for a cozy way to pass a snowy day.

Top Right: PEM boasts the world’s largest collection of Chinese export art, including this lavishly carved 19th-century moon bed. (Photo: Kathy Tarantola/PEM)

Bottom Right: A rotating but always colorful selection of ensembles worn by fashion pioneer Iris Apfel and her husband, Carl, fills the gallery named in their honor. (Photo: Peabody Essex Museum)

Peabody Essex Museum | Salem, MA

Born from the treasures East India Marine Society seafarers amassed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum has been called a “collection of collections.” So, cliché as it sounds, this museum really does offer something for everyone—including my 4-year-old daughter.

During our visit last January, she relished the backyard birds on display in The Pod, part of the family-friendly Dotty Brown Art & Nature Center, and the interactive “Salem Stories” exhibit, which traces the city’s journey from witch trials epicenter and global shipping mecca to the vibrant, multicultural hub it is today. The maritime art gallery was an unexpected hit, especially the “step inside to discover” alcoves: Enter, settle on a bench, and take in the highlighted artifact or artwork—such as a “calendar” stick notched by a castaway to mark the days he spent stranded—while listening to its origin story.

Another multigenerational favorite was the Carl and Iris Barrel Apfel Gallery of Fashion & Design, where we oohed and ahhed over mannequins done up in fabulous designer duds and chunky jewels. My daughter deemed them “fancy,” while I, a former fashion editor, fangirled over the late Iris Apfel’s sartorial significance.

We moved on to Anila Quayyum Agha’s All the Flowers Are for Me, craning our necks as we slowly strolled around the illuminated and suspended laser-cut steel cube. The sculpture cast intricate shadows against gallery walls that were painted yellow because Agha, as she put it, was “interested in bringing sunlight into the room.”

Also warming—at least in spirit—was the fireplace flickering with digital logs in the Sean M. Healey Family Gallery, where street sounds and music immerse visitors in the floor-to-ceiling wallpaper that once hung in Strathallan Castle in Scotland. A scavenger hunt encourages closer inspection of the 19 panels, depicting life and trade in Guangzhou, China. (Example: Can you find this mother trying to pull her mischievous child off of the rattan roof of their sampan?)

We didn’t finish the full hunt, nor did we make it to PEM’s famous Yin Yu Tang House. A late lunch (the kids ramen at Kokeshi) was calling. But we already have plans to return to explore the 16-bedroom home originally built in China during the Qing Dynasty, reconstructed in Salem, and installed on the PEM campus. Because that’s a hallmark of a truly great museum: There’s always something calling you back. pem.org

Bottom Left: Roses crafted from seashells adorn Brian White’s 2006 sculpture Rose Arbor/Sea Street, part of the Farnsworth’s permanent collection.

Bottom Right: A gallery entrance frames one of the famous “Love” sculptures by American pop artist Robert Indiana.

All Photos by Katherine Keenan

Farnsworth Art Museum | Rockland, ME

Jamie, Andrew, and N.C., oh my: There’s no name more associated with the Farnsworth Art Museum than Wyeth. Since its founding in 1948, the Rockland institution has been intertwined with the three-generation painting dynasty, and today it boasts a Wyeth Center and owns the Olson House in nearby Cushing, Maine, the setting for several of Andrew Wyeth’s most well-known paintings, including Christina’s World.

What’s more, the Farnsworth counts many Wyeth masterworks among the 15,000 or so items in its ever-expanding collection, which celebrates Maine’s outsize role in American art. (Also see: Winslow Homer’s seascapes, an aluminum LOVE sculpture by the late Vinalhaven resident Robert Indiana, and more.)

But the museum, which marked its 75th anniversary in 2023, isn’t stuck in the past. In a way, it’s a reflection of Rockland itself, which has seen a revitalization in recent years with cool restaurants and artisan shops putting down roots.

I first found proof of the Farnsworth’s forward-looking ethos in the mural flanking the entrance, You Showed Me Love. Portland-based artists and couple Rachel Gloria Adams and Ryan Adams—self-described “weird art kids”—emblazoned the museum’s facade with bright geometric patterns and stylized lettering that quotes the Frank Ocean song they heard on their first date.

Speaking of futuristic, the Farnsworth also has the second-largest collection of works by ahead-of-her-time sculptor Louise Nevelson. While the recent “Dawn to Dusk” exhibition featured the monochromatic scrap-wood constructions she’s known for, it also included early oil paintings, collages, and funky jewelry. Nevelson, who emigrated from Ukraine to Rockland in 1905, once called the Farnsworth “something that I had not expected in my wildest dreams to find in a town in Maine—that jewel that shines.”

Perhaps the most striking example of how the Farnsworth is looking ahead is “Momentum,” a new exhibition series that launched last year showcasing the next generation of Pine Tree State artists. Each year, the museum provides an artist with their first solo show, acquires an artwork for its permanent collection, and publishes a scholarly catalog. First up was Harpswell’s Emilie Stark-Menneg, whose wildly colorful, tapestry-inspired acrylic paintings depict maidens and unicorns frolicking among flowers and fruit—a far cry from meditations on Maine’s rocky coastline or weathered fishermen.

All of this isn’t to say a Wyeth exhibit can’t be fresh, too. Last summer’s “Abstract Flash: Unseen Andrew Wyeth,” presenting never-before-seen works spanning six decades, floored Boston Globe art critic Murray Whyte. “It is nothing less than a thrill,” Whyte wrote, “both as vital connective tissue in the Modern American canon, and as a simple, indulgent pleasure of a great artist revealed in new layers.” He knows what I learned firsthand: The Farnsworth—and the town it calls home, for that matter—is full of surprises. farnsworthmuseum.org

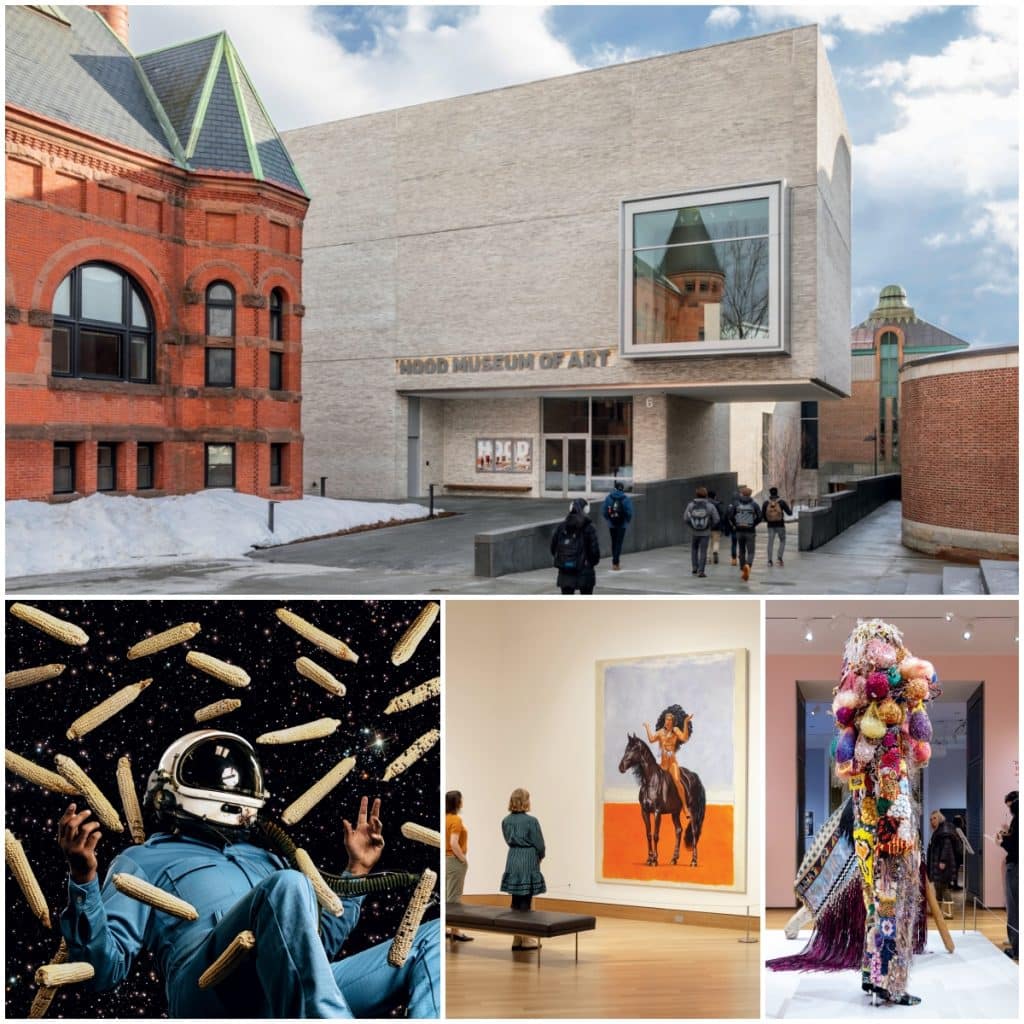

Bottom Left: Cara Romero’s The Zenith, part of the Chemehuevi photographer’s first major solo museum show, on view from Jan. 18 to Aug. 10, 2025. (©Cara Romero, Zenith, 2022, purchased through the Acquisition and Preservation of Native American Art Fund, Hood Museum of Art)

Bottom Middle: Visitors contemplate Cree artist Kent Monkman’s 2023 painting The Great Mystery. (Photo: Rob Strong)

Bottom Right: A side view of the textile-based sculptures Soundsuit by Nick Cave (foreground) and What Do You Want? When Do You Want It? by Jeffrey Gibson. (Courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth)

Hood Museum of Art | Hanover, NH

Cloaked in white and surrounded by mountains and rivers, the Dartmouth College campus in late winter is a scene straight out of a snow globe. But the sleepy setting belies one of the country’s largest and most exciting university art collections.

Representing six continents, the Hood Museum of Art’s 65,000 holdings range from hulking, nearly 3,000-year-old stone reliefs from Assyria to one of Nick Cave’s sequin-and-mirror-bedecked Soundsuit sculptures. And with the 2019 debut of a dazzling renovation and expansion, the museum now has a fitting home for this world-class collection. Passersby can get a literal sneak peek of its treasures in the north facade’s imposing picture window, which often frames an important painting or sculpture.

Because the Hood is manageable in size and not particularly crowded, it allows you the time and space to savor this worldly art buffet at your own pace. Docents are quick to answer questions or chat, but they’re also perfectly content to let museumgoers explore.

On my visit, I was a globetrotter. The temporary exhibit “Connecting Threads and Woven Stories” featured textiles from Southeast Asia—including a Thai wall hanging woven with jewel beetle wings (!)—while up on level two awaited new-to-me abstract paintings, all earth tones and arresting patterns, by contemporary indigenous Australian artists. I especially lingered over the works in “Homecoming: Domesticity and Kinship in Global African Art,” a show centering the role of women artists and feminine themes in African and African diaspora art. The oversize quilts were the stars, including the recent Hood acquisition It’s a Blue World by Bhasha Chakrabarti, tracing the history of the global indigo trade.

I ended my visit in the Engles Gallery, where the aforementioned picture window overlooks the college green. Also set up there: an opt-in art project inspired by Chakrabarti’s work, prompting participants to draw a cherished object on a brightly colored square and add it to a “quilt” on the wall. My eyes darted between the outside world in quiet afternoon shades of gray and the rainbow-paper tapestry before me, pulsing with life. And while I still had all of the rest of Hanover to explore, that would have to wait; I sat down and began to sketch. hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu

Bottom Left: Work by SVAC member artists in the Yester House. (Photo: David Barnum)

Bottom Middle: An image from the blockbuster traveling exhibit “The Red Dress,” which made its U.S. debut at SVAC in 2023. (Courtesy of SVAC)

Bottom Right: Three Generations by Susan Abbott, part of the current SVAC exhibition “Lineages: Artists Are Never Alone,” through Feb. 23, 2025. (Courtesy of SVAC)

Southern Vermont Arts Center | Manchester, VT

It was snowing hard as we wound our way up the almost-mile-long driveway to the Southern Vermont Arts Center. Flecked with white in the waning afternoon light, the sculptures lining the road and dotting the fields appeared otherworldly. All was hushed, in contrast to the buzzing town center we’d just left, where tourists hunkered down in the charming inns and cozy farm-to-table cafés Manchester does so well.

But any illusion that we’d entered a frozen fairy-tale land melted away when we reached the busy parking lot. In fact, what we didn’t know yet was that we had found the beating heart of the southern Vermont arts community.

Our first stop on the 100-acre-plus campus was the modern, many-gabled Wilson Museum. Opened in 2000, it hosts traveling exhibits as well as the center’s permanent collection showcasing works from artists active in the Southern Vermont Artists collaborative in the early 20th century. On the day we visited late last January, we were ushered into a bustling reception for two installations grappling with violence against women: Cat Del Buono’s Voices and Nayana LaFond’s Portraits in RED. It was tough, honest stuff, and all around me, people were literally leaning in. And once visitors left the gallery, they couldn’t stop talking about it, to each other and to Del Buono, who was on-site for the event.

That community feel extended across the sculpture-strewn green to the circa-1917 Yester House, home to the Southern Vermont Artists Inc. since 1950. In the annual SVAC Fall/Winter Member Exhibition, works by 300-plus member-artists from New England and New York in various media—from painting and photography to ceramics and fiber arts—filled the homey galleries, several bearing “sold” signs. Jessica Rhys’s oil paintings of owls accented with gold leaf and Barbara Ackerman’s abstract multimedia etchings especially caught my eye. To keep the conversation going, there are gathering spots throughout the historic house (think Oriental rugs, fireplaces, comfy chairs, and shelves piled with art books), as well as the upscale curATE café, open year-round. Because at SVAC, you can’t help feeling part of the area’s long-running artistic dialogue. It’s a sentiment underscored by the words on the official historic roadside marker near the entrance: “Hundreds of artists show and perform annually, and thousands attend programs, continuing the traditional search for creativity in the inspiring hills and small villages of southern Vermont.” svac.org

Bottom Left: In the modern Krieble Gallery, visitors ponder Mark Dion’s New England Cabinet of Marine Debris (Lyme Art Colony), which was commissioned by the Flo Gris and created in part on the museum’s grounds. (Photo: Allegra Anderson)

Bottom Right: Everett Warner’s Winter on the Lieutenant River memorializes the picturesque waterway behind Griswold’s home. [Winter on the Lieutenant River, Everett L. Warner (1877-1963), courtesy of Florence Griswold Museum, Gift of the Trustees in Honor of Jeffrey Andersen]

Florence Griswold Museum | Old Lyme, CT

Your first inkling that the Florence Griswold Museum is a New England art museum like no other is the short documentary you’ll see in the Visitor Lounge, introducing the artists who established the famed Lyme Art Colony at the turn of the 20th century. Until Florence Griswold’s death in 1937, her Georgian manse turned boardinghouse was ground zero for these American tonalists and Impressionists—and there’s history around every corner at the Flo Gris, as it’s affectionately known.

As I took in the wall panels painted by one-time guests Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, and William Chadwick and wandered the mansion’s period-perfect rooms, I got a real sense of the lived experience of the painters and sculptors who found Miss Florence’s home to be, as Hassam called it, a “little excursion into Bohemia.” And I could see how they gleaned inspiration from the rural beauty of the Lower Connecticut River Valley—a beauty that the Old Lyme-Essex-Old Saybrook area, while brimming with inviting shops and artful attractions, still retains today.

With highlights from the museum’s vast collection now rotating through the modern Krieble Gallery also on campus, there are even more opportunities to get up close and personal with these important American artists. Don’t miss the glass case displaying Chadwick’s palette, Metcalf’s sketches and diary, and a paint box that belonged to miniaturist Lydia Longacre, a rare female colony member. Also on view are two “wiggle” sketches, from artists who played the raucous Wiggle Game in the nearby boardinghouse parlor—one artist would draw a number of squiggles on paper and dare the next artist to incorporate these flourishes into a finished sketch.

This idea of living history comes into sharp relief while strolling the half-mile Robert F. Schumann Artists’ Trail around the museum’s property. Although I didn’t catch Miss Florence’s prized gardens in bloom, I did spend time roaming the banks of the Lieutenant River. Not only did the Lyme Colony artists once paddle rowboats there, but they also found a muse: Everett Warner’s painting Winter on the Lieutenant River, for one, depicts tawny marsh grasses poking through patchy snow on the water’s edge.

The trail opened in 2019, one of the most recent additions to this preservationist’s dream, which also saw the donation of a 190-piece Connecticut art collection from the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company in 2001, and the opening of the undulating Krieble Gallery in 2002.

But back to the artists and their antics: The oft-quoted Hassam once stated that Griswold’s boardinghouse was just the place “for high thinking and low living.” So while I reveled in the art history all around me—I also found myself wishing the walls could talk. florencegriswoldmuseum.org