New England

Encyclopedia of Fall: A is for acer saccharum (sugar maple)

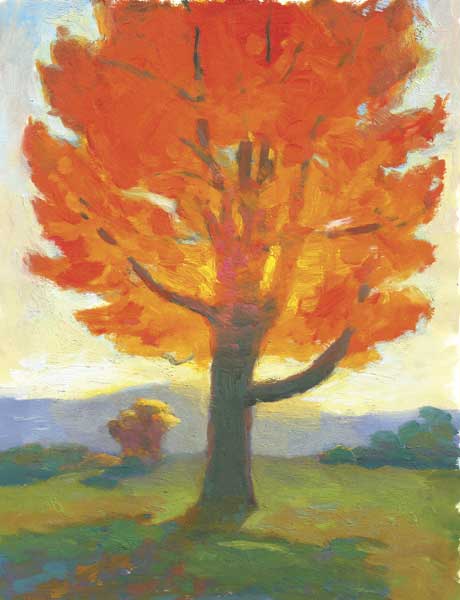

What is acer saccharum? New England’s beloved sugar maple, of course.

Photo Credit : Garns, Allen

Because rural New England is a well-watered and well-wooded region, people here live much with trees–trees not only as a natural resource, but for other purposes, as well. Every country place has on it one or more trees that are more than large, unmoving elements of the landscape. They are familiar spirits–proprietary trees, so to speak–domesticated trees, trees that owing to their beauty, their history, their location, seem to have a special connection to the place and the people on it.

In the Green Mountain foothills of Vermont, where I live, favored trees of the kind I’ve described are very apt to be sugar maples. Whether grown by nature or by design, they are our preeminent roadside and dooryard trees. I have one immediately outside the window of the room where I work. Maybe because it stands no more than a few feet from where I sit, this particular maple has come to be for me a kind of companion.

My window maple is an unremarkable specimen. It’s probably 60 feet tall, maybe 75 years old. I can estimate its age with some confidence from the size of its base, and also because it has been a part of the setting here for not that much longer than I have. An old-fashioned black-and-white snapshot of this house, taken in 1961, shows the same maple as a young tree, little better than a sapling. Fifteen years later, when our family arrived, it had about the girth of a sturdy fencepost. Today it’s a mature tree.

Growing in the open as they do, the maple’s lower branches have extended obliquely, to reach the sunlight beyond the upper parts of the tree. This has given the tree the characteristic egg shape of the classic sugar maple, and it has provided us with convenient beams for hanging bird feeders, swinging ropes, and outdoor thermometers.

Our maple has been a good friend to our family over the years, and perhaps especially to me. How many hours, weeks, seasons have I spent looking out my window at this tree? I don’t know; I can’t count that high. Now, the job of writing is one that can honestly involve a certain amount of sitting and gazing out the window. Believe it or not, a writer’s work can be accomplished that way–at least part of it can. Or so writers are pleased to let on. Perhaps only my window maple and I know how much of my own looking has accomplished nothing at all.

To be sure, the sugar maple has uses beyond furnishing matter for meditation to the easily distracted. No tree in New England works harder on man’s behalf. It is by no means the biggest tree in our woods; the oldest pines and hemlocks regularly grow taller. It’s not the longest-lived; those same pines and hemlocks, and some oaks, go back further. Nor is it our most celebrated, or storied, tree, an honor that must go to the American elm, decimated by disease in recent decades, but whose survivors recall the beloved elms, of which every New England village formerly seemed to have had one, under which George Washington must surely have stopped to refresh himself once upon a time.

Lacking grandeur, antiquity, and legend, the sugar maple succeeds through industry. It is unsurpassed in the diversity and excellence of its utility. The value of its sap in producing syrup and sugar is widely known. Less appreciated is the value of its wood. Hard and closed-grained, sugar maple makes flooring more durable than marble, hence its use in basketball courts and bowling alleys. Around the house it’s ubiquitous–in tubs, bowls, cutting boards, rolling pins, wooden spoons–for the making of any implement subject to long, hard wear, not only kitchen implements, but baseball bats, billiard cues, bowling pins, drumsticks, gunstocks.

Since it can be cut with precision, and because of its rare birdseye and other fancy grains, sugar maple has been prized by woodworkers since the beginning of American cabinetmaking. In addition, again because it can be worked to fine tolerances, and also because of its acoustic qualities, makers of musical instruments often use it in violins, cellos, guitars, and other strings, in some woodwinds, and in drum shells.

Finally, however, the sugar maple’s signal gift to our region is not a gift of use. It’s not a gift of fanciful fellowship. As I write this, on a warm afternoon in early October, the leaves of the companionable tree at my window have turned a fine, translucent lemon-yellow. They seem lit from within. Up and down the road, sugar maples spread their scarlets and oranges in the sun, bestowing once again the gift of color, the gift of brightness, the gift of autumn.