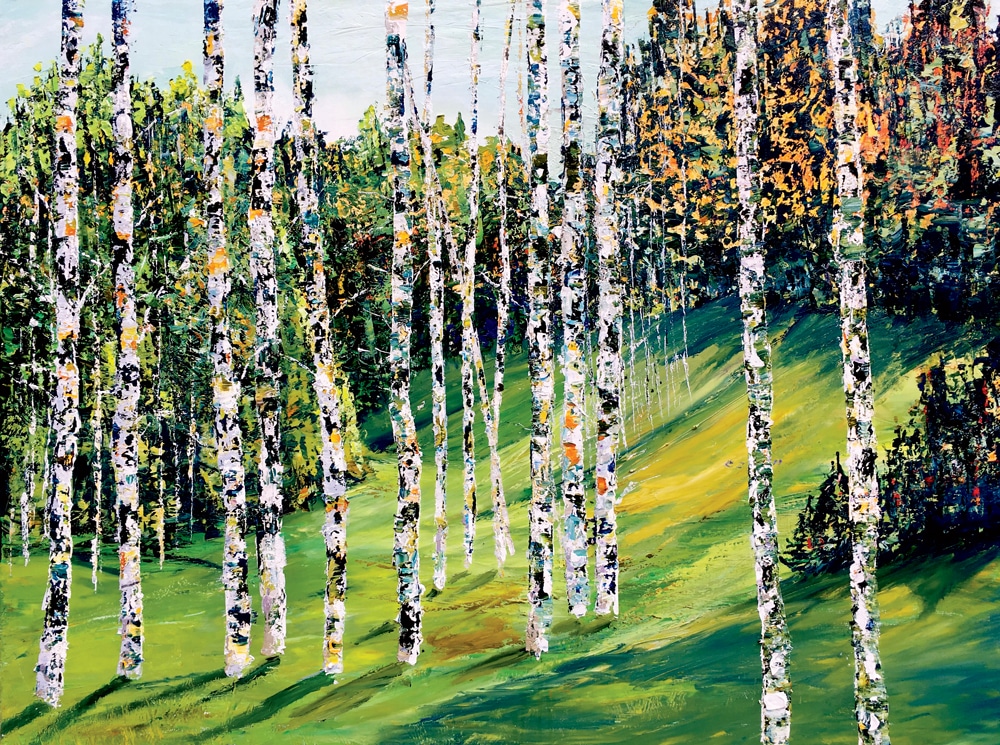

The Artist’s Tree | First Light

There’s a reason that photographers and painters are drawn to the white birch.

Massachusetts artist Julia S. Powell says her 2016 painting Autumn Hill, like much of her work, was inspired by her frequent rambles through the New England countryside.

Photo Credit : Julia S. Powell

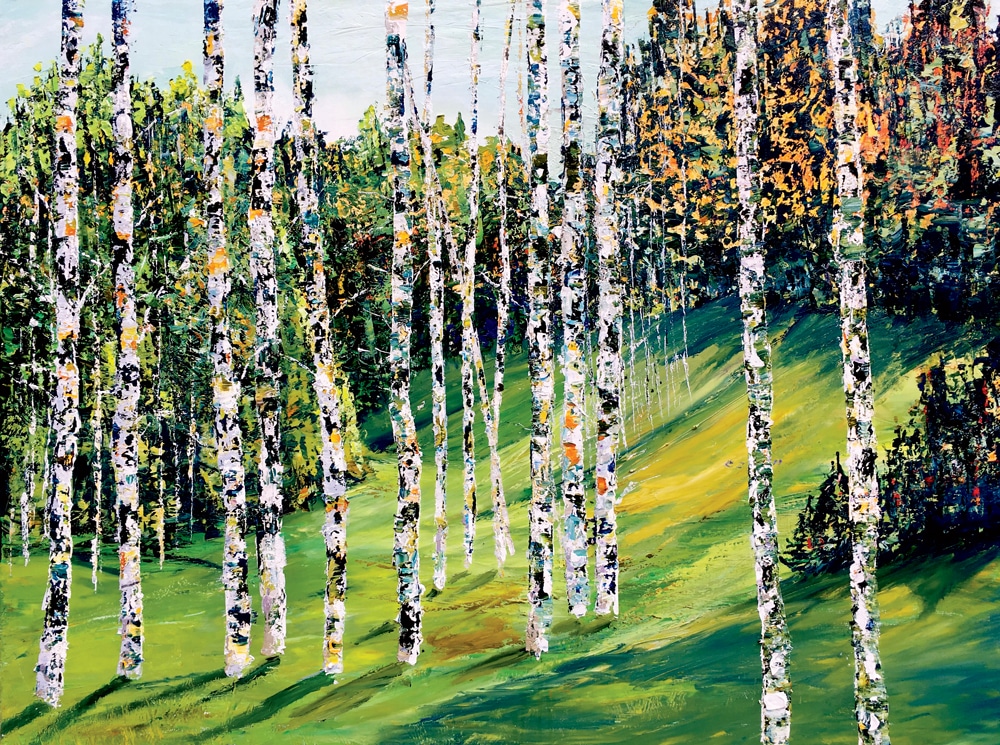

Photo Credit : Julia S. Powell

If the forests of the North had lacked the white birch tree, then the painters, printmakers, watercolorists, photographers, and other visual interpreters of New England would have been obliged to invent it. No tree, no other part of our outdoor setting, has been of more use to art. Through all four seasons and in a variety of surroundings, the white or paper birch (Betula papyrifera) reliably supplies what landscape designers call “visual interest.” It’s by no means a flamboyant, show-offy tree, but by its unique coloration and habit of growth, it makes its pale, slender presence very welcome. It’s not for nothing that the white birch is New Hampshire’s officially designated state tree.

Birch trees don’t so much add to an outdoor scene as construct it. If you’re on a bushwhack in the woods of southern Vermont, where I live, you may find the forest around you hard to grasp: a shifting, blending, flickering curtain of greens, shading into one another, largely unrelieved save by the birches, whose familiar white trunks mark out the perspective that lets you know where you’re going.

Some of America’s best-loved painters, especially of the 19th and 20th centuries, made good use of the white birch’s aptitude for creating focus in landscape: Winslow Homer, Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, Frederic Remington, John Singer Sargent, Georgia O’Keeffe.

Their affinity for the birch tree is easy to understand. The alabaster trunk, white and smooth as schoolroom chalk, with its black bands and patches where the bark has been removed or injured, makes a sharp and vivid stop for the eye. It makes a contrast—and contrast is where art begins, or near enough. Isn’t it? However that may be, the birch, like a kind of natural plein air still life, seems to insist on being painted. This tree makes impressionists of us all.

The tree is a mainstay of art classes. Students and instructors have found it the ideal subject. It’s hard to get a birch tree wrong.

None of this is to say that the white birch’s value is confined to the artistic. Not at all. We are talking about one of the most useful, most versatile trees in our woods. The hard, pale, close-grained wood of the birch is popular with woodworkers for its natural satiny finish and fancy grains similar to the maple’s. Birch wood gives us household ware from bowls to spoons to toothpicks. For its light weight, it’s an unexpectedly strong wood that makes excellent veneer and interior plywood, including for skateboards, kitchen cabinets, even light aircraft.

The best-known of the birch tree’s many products, however, must be the legendary bark canoes built by the forest Indians of North America going back to prehistory. These remarkable vessels, miracles of Neolithic naval engineering, take advantage of white birch bark’s singular flexibility and tensile strength. Sheets of bark were stripped from the birch’s trunk, cut to shape, stitched together, fastened down onto a wooden frame, and caulked tight. The result was a light, graceful structure of extraordinary strength, able to float bearing a burden many times its own weight.

Today, the making of birchbark canoes figures mainly as a traditional craft. More up to date is another of the birch tree’s beneficial applications: as food and medicine. Birch trees can be tapped like maples and their sap enjoyed as syrup or as birch beer. To many, the syrup is heavier and closer in taste to molasses than maple syrup. It’s not as sweet as maple, and therefore needs more refining. Sugar maple sap boils down to syrup at a ratio of 40 gallons of sap to one gallon of syrup; the ratio for birch sap is 100 gallons to one. Good, sound New England Yankees that they are, the birches make you work a little harder for your treat.

Herbalists use and praise every part of the tree: leaves, twigs, bark, root. Various preparations of birch leaves have been used as a sleeping draft, a diuretic, a wash for skin lesions, a solvent for kidney stones, and a specific for gout, rheumatism, and arthritis. The white birch is the apothecary shop of the north woods.

But although the birch tree is generous in its gifts to us, it’s not alone in bestowing those gifts. Other trees supply wood for our many projects; still others please our palates and minister to our complaints. To conclude our celebration of the white birch tree, we pass by the utilitarian and come around again to considerations of art.

The white birch is not a rich maker of autumn color. Its leaves turn a pale, subdued yellow. They concede the brightest display to the sugar maples, poplars, and sumacs that dominate the hillside palette. It’s when other trees’ leaves have gone that the birches’ shining trunks show forth to do their work of perfecting the season by repeating in the woods the classic white clapboards and black shutters of our hamlets and villages. The white birch tree is much loved in New England because it shows New England to itself.